Before Pina Bausch (1940–2009) choreographed for Kurt Jooss’s Folkwang Tanzstudio, before she took over Wuppertal Ballet and renamed it Tanztheater Wuppertal, before she startled the world with her radical imagination, she had been to Juilliard and worked with choreographers in New York City. An artist who avidly embraced new experiences, she once defined her form of tanztheater as “a space where we can encounter each other.”[1] I maintain that the encounters during her two years in New York contributed more to her development than most Bausch scholars have acknowledged.

[Let me say right here that the footnotes are woefully out of order. Sorry for the inconvenience, but I made cuts some months ago, and it was confounding for me to try to re-order them in this format.]

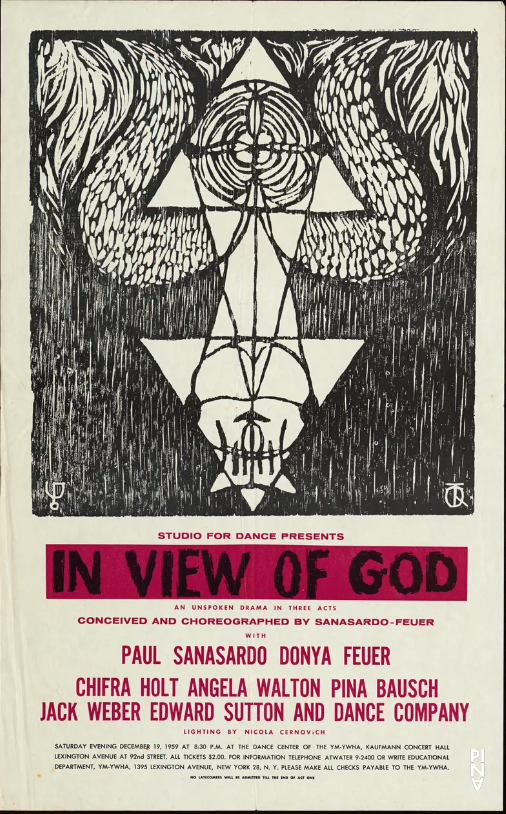

Some scholars claim that American dance, with its formalist concerns supposedly in the forefront, had little effect on Bausch.[5] I attribute this view to a misunderstanding of what was considered “mainstream modern dance” in those years. The formalism of Merce Cunningham was quite marginal at the time, while Graham’s aesthetic—the emotional core of the modernist narrative—still held sway. The concert series at the 92nd Street YM-YWHA, the stronghold for modern dance in New York, was packed with former Graham dancers including Pearl Lang, Anna Sokolow, Paul Taylor, Yuriko, and Sophie Maslow. Many of them were teaching at Juilliard. (Bausch herself performed there in December 1959 with Paul Sanasardo, in his work In View of God [6], more about this later).

Merce Cunningham was rarely invited to perform at the Y in the fifties, nor was he on the Juilliard faculty. He wasn’t widely accepted until the success of his 1964 world tour. (He too had danced with Graham, but his choreography departed so radically that it pushed beyond “modern dance” into another category that was called “contemporary dance” or sometimes “abstract” dance). Judson Dance Theater, which erupted with the bold experimentation that ushered in post-modern dance, didn’t emerge until 1962—and even then, it was below the radar. So the Juilliard dance department, with its director Martha Hill (herself a former Graham dancer), was basically aligned with the center of modern dance at the time.

The New York influence on Bausch was threefold. First, her Juilliard teachers, most of whom were international figures: Antony Tudor, Alfredo Corvino, José Limón, Graham (especially through company members Mary Hinkson and Donald McKayle) and to some extent, La Meri, Louis Horst, and Anna Sokolow. Second, the choreographers she worked with outside of Juilliard: Paul Sanasardo and Donya Feuer, Paul Taylor, and again, Tudor, at the Metropolitan Opera Ballet. Lastly, the sheer diversity of styles, ethnicities, and music genres that populated New York at the time.

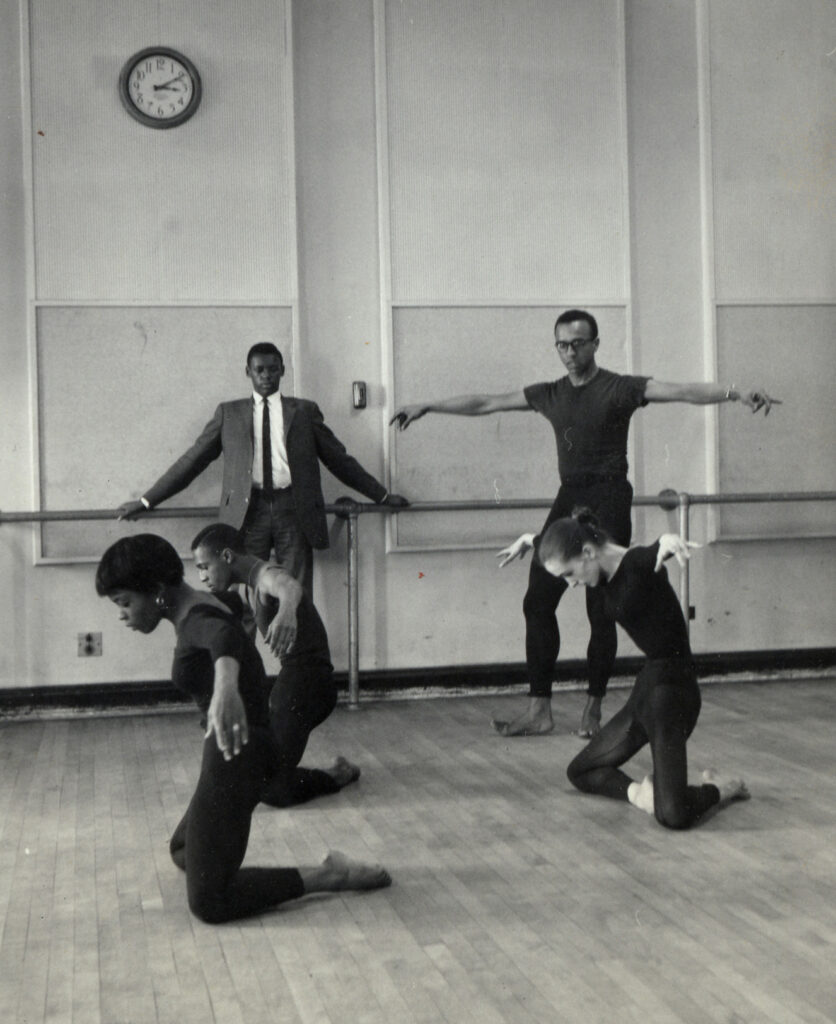

Graham technique at Juilliard. From left: William Louther, Martha Hill, Donald McKayle (teaching the class), Dudley Williams, Mabel Robinson, and Pina Bausch. Photographer unknown, Courtesy Juilliard Archives.

My purpose is to open a window into that period of the young Pina Bausch in New York. I discuss the range of styles she participated in at Juilliard, her close—and fraught—relationship with Tudor, her performances in the year-end school concert, and her friendship with a diverse group of students. I also describe her immersion in the work with Paul Sanasardo and Donya Feuer in Chelsea; her brief time with Paul Taylor at Spoleto; her stint with the Metropolitan Opera; and her attraction to Sokolow’s work. Although it doesn’t fit into the two-year span, I also include her four weeks at Saratoga in 1972, where, through Sanasardo and the late Manuel Alum, she met two dancers who were essential to the creation and longevity of Tanztheater Wuppertal Pina Bausch.

Crossing the Atlantic

From the age of 14 to 18, Philippine (her given name) Bausch studied dance with Kurt Jooss, director of dance at the Folkwang School in Essen. Jooss was a proponent of Austruckstanz but veered off from Rudolf Laban’s movement choirs to develop tanztheater as a concert form. Jooss was a prolific choreographer; his company toured extensively throughout Europe before and after World War II. His anti-war ballet, The Green Table (1932), is one of the iconic works of the twentieth century. A leading educator as well, Jooss developed a training method that combined the strength and clarity of ballet with the weight and effort flow of Laban.

Pina benefited from the multi-arts nature of the school. In 2002, she told The Guardian, “At this time at the Folkwang, all the arts were together. It was not just the performing arts like music or acting or mime or dance, but there were also painters, sculptors, designers, photographers.”[8] At the end of her last year there, she won the Folkwang prize, possibly the first dancer to be so recognized. A grant from the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD) funded her sojourn to the Juilliard School of Music (now simply the Juilliard School).

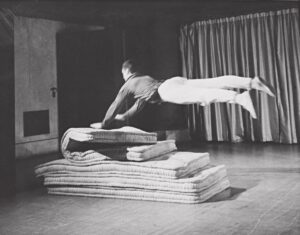

Lucas Hoving teaching a Composition Materials class, Photo © Radford Bascome, courtesy of the Juilliard Archives.

Lucas Hoving, the Dutch dancer who had worked closely with both Jooss and Limón, was a link between the Folkwang School in Essen and Juilliard, having taught in both schools. Like Jooss, Hoving combined ballet and modern vocabularies in his technique classes. After her ship set sail from the port city of Cuxhaven to New York in the fall of 1959, the 18-year-old Pina wrote to Lucas, asking him to meet her at the New York harbor. Almost five decades later, when receiving a Dance Magazine Award, she told a poignant story about the way New York welcomed her, which I repeat at the end of this essay.

Friends, Classes, and Spirit at Juilliard

Pina loved the cultural and racial diversity at Juilliard. On the day she auditioned for placement levels, she met Rina Schenfeld, a young dancer who had sailed from Israel. Neither could speak much English, but they bonded immediately. The two shared the experience of outsiders who were welcomed. As Schenfeld told me, “We were both foreigners, and we were treated so beautiful, like real important guests.”[9]

Pina also made friends with a group of Black students that included Sylvia Waters, Mabel Robinson, William Louther, and Dudley Williams (all of whom became major figures in the New York dance world). Sylvia told me about a holiday dinner, probably in the fall of 1959:

I remember one Thanksgiving she [Pina] spent with me and Mabel Robinson and, I think, Dudley and Bill Louther. I’d never seen her eat so much! We all ate a lot, and we all fell asleep instantly, and woke up and ate again…We were young and just having fun… it was a new experience for her, to have a traditional Thanksgiving, especially with a Black family.[10]

The comfort she felt with African American dancers gives us a glimmer of her later commitment to diversity with her Wuppertal company.

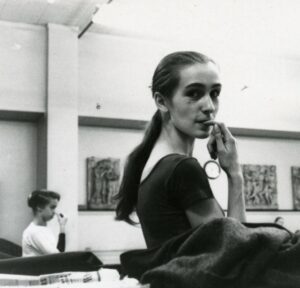

Pina Bausch and Mercedes Ellington in rehearsal. Photographer unknown, courtesy of the Juilliard Archives.

Pina was friendly with other students too. Carla De Sola, who had never taken ballet, remembers, “She would come to where I was at the barre and she would help me, give me pointers…on tendues, pliés, basic footwork…It was a kindness on her part.”[11] And Mercedes Ellington recalled, “Pina was teaching me German by body part: obershenckel [thigh] unterschenkel [lower leg].”[12]

Ellington was living in a room next to Bausch’s at International House, down the block from the Juilliard building, then on Claremont Avenue in the Columbia University neighborhood. They both worked in the cafeteria, alternating chores like tending the cash register and bussing tables. “Her favorite dessert was strawberry ice cream,” Ellington told me, “and she poured sugar over the ice cream and squeezed a lemon on top of that.” Did Pina smoke? “Smoking: always; everybody was smoking back then.”

Most students in the dance department had to choose between majoring in ballet or modern dance, and if the latter, between Graham and Limón. As a special student, Pina could take any classes she wanted.

Standing: William Louther, Donald McKayle. On knees: Mabel Robinson, Dudley Williams, and Pina Bausch, Photographer unknown, Courtesy Juilliard Archives.

The Graham technique, based on contraction and release initiated in the pelvis, is emotional—an expression of either ecstasy or despair— and yet the technique is modernist in its stark shapes. In a photo of Bausch’s early work Aktionen für Tänzer (1970-1971), she passes through a high contraction in the Graham style, very much like the photo above. In a more general way, the Graham influence can be seen in how deeply visceral the Bausch dancers’ solos are, how the movement is initiated in the center of the body. The Humphrey/Limón style is softer and more fluid, concentrating on fall and recovery (or fall and suspension), with a more lyrical flow.

Although these techniques were new to her, Pina entered them with the high level of artistry she attained at Jooss’s school. Sylvia Waters remembers, “She had very clean lines and she was unique. She rather shimmered onstage… quiet, strong, fluid…such clarity.”[13]

At Juilliard, Pina was totally focused on dance. “I never thought I would become a choreographer. I only wanted to dance,” she declared in a speech titled “What moves me” that she gave upon receiving the Kyoto Prize in Arts and Philosophy in 2007.[14] Schenfeld (who later became the magnetic star of the Batsheva Dance Company), confirms this, saying she was surprised when she learned that Pina was choreographing in Germany.[15]

That said, the German student was fully active in Louis Horst’s “Modern Forms” class at Juilliard. Horst, the composer who had mentored Martha Graham and given structure to her choreography, assigned studies for certain categories of dance styles. The Juilliard archive shows that in October Pina composed and danced “Girl In A Big City” to music by Gershwin, and for the December workshop she co-composed a “Whole Tone” study with music by Lothar Windsperger. This last was for an assignment called “Exercises in Space, Volume and Time.” For the showing in March, she created a solo in the “cerebral” category called “Mechanics on Parade,” with music by Ernst Toch, and in the “jazz” category, “Madison Avenue” to music by Edgar Fairchild.[16]

Janet Mansfield Soares, author of biographies on Martha Hill and Louis Horst and a former assistant to Horst, recalled that “Pina’s solutions were right on-point. She understood Horst’s assignments (ranging from linear to dissonant, cerebral to impressionist). I do believe his teaching gave her a strong aesthetic grounding for her lifetime of extraordinary work.” [17]

I agree that she may have absorbed Horst’s teachings insofar as he demanded rigor and cogency in the studies. However, the structure he taught was basically A-B-A, or theme-and-variations, whereas Bausch favored a collage-like structure in her work. A bonus in the classes with Horst, though, was that he would sometimes speak German with her.[18]

Bausch worked with non-white dancers every day at Juilliard. The Graham technique classes were taught by members of her company including notable Black dance artists Donald McKayle and Mary Hinkson. Pina took classes from Mexican-born José Limón and was probably directed by him in Doris Humphrey’s Passacaglia (1938). In Tudor’s Little Improvisations, she understudied Ellington, the granddaughter of Duke Ellington, and, in A Choreographer Comments, she danced alongside Japanese-born Chieko Kikuchi (no relation to Yuriko Kikuchi).

This diversity opened her eyes. Coming from a country whose führer committed genocide in order to narrow humanity down to a single genetic race, she valued (in my opinion) this more open world. When talking about New York, she said,

The people, the city, all embody something of now for me, where everything is mixed together, whether that’s different nationalities or interests or fashion, everything is just side by side.[19]

When she reshaped Wuppertal Ballet into Tanztheater Wuppertal in 1975, she started building an international company. By the 1990s, the Wuppertal dancers hailed from every continent except Antarctica.[20] Her group included Black, Asian, and LatinX dancers, as she said, “side by side.”

This diversity, and with it a sense of independence, reflected a spirit about Juilliard that Schenfeld feels helped shape Bausch, the artist: “What Juilliard gave us—it’s not the steps—it was an international, individualistic attitude, which is America, which is what New York was then. Freedom of individuality. It’s the essence of things…not teaching us to be soldiers. And that’s how she really developed and found herself.” [21]

Bausch and Schenfeld remained lifelong friends. Whenever Tanztheater Wuppertal performed in Israel, they had long visits, sometimes attending local celebrations together.[50]

The Tudor Connection — Deep and Long

Antony Tudor was known for his psychological ballets, for his ability to turn a well-timed gesture into a pivotal narrative moment. It was no secret that Pina was a favorite of Tudor’s. Ellington called her his muse: “There was a strong connection between her and Tudor, they spiritually understood each other.… she was acclimated to his style, so he paid a lot of attention to her.” He gave Pina leads in his ballets, even though pointework was not her forte. (He gave Ellington the lead in his Little Improvisations, which she danced with Bill Louther. Pina was in the second cast of this duet.)

Carla De Sola recalls a period when Tudor experimented with an improvisational component in class, which may have been part of his course called Ballet Production or Rehearsal or possibly Ballet Production and Arrangement:

Tudor had a tiny little composition class at the end of ballet class… and Pina Bausch was always spectacular. He would say, “Would you go across the floor and let us know where you are, what environment, by just how your body is? Is it moonlight? Is it sunlight?” And she would know how to do that! He was interested in someone who could convey something…not necessarily just through the steps but the way she carried herself, or her aura.[22]

Bausch believed in Tudor totally. The Tudor Centennial project (2008 to 2010) gave her an opportunity to look back and sing his praises:

His way of using and extending the classical dance technique was absolutely groundbreaking—for both classical and modern dance. He was the first to bring his Grandparents’ [sic] clothes onto the stage. He was in many things the first. I was of course full of admiration for him. His ballets were wonderful, but very, very hard to dance. In his pieces it needed a very special sensitivity for this fineness of feeling, accuracy, and humour. He was incredibly critical, especially about himself.”[23]

Although Pina was supremely classical in her balletic lines and port de bras, she did not have strong feet. About her efforts on pointe, Schenfeld remembers, “She didn’t feel she was doing the best for Tudor. She didn’t talk about it. I just saw her suffering.”[24] Viewing the archival film in the Juilliard archives, one can see that Pina could barely sustain pointework. Her ankles were so weak that, when on pointe, her supporting foot looked as if it could have crumpled at any moment. Bausch wrote in her Tudor reminiscence, “Once…while we were performing his piece A Choreographer Comments, I fell off pointe. I hardly dared to look him in the eye. I could have jumped into the Hudson River out of shame.”[25]

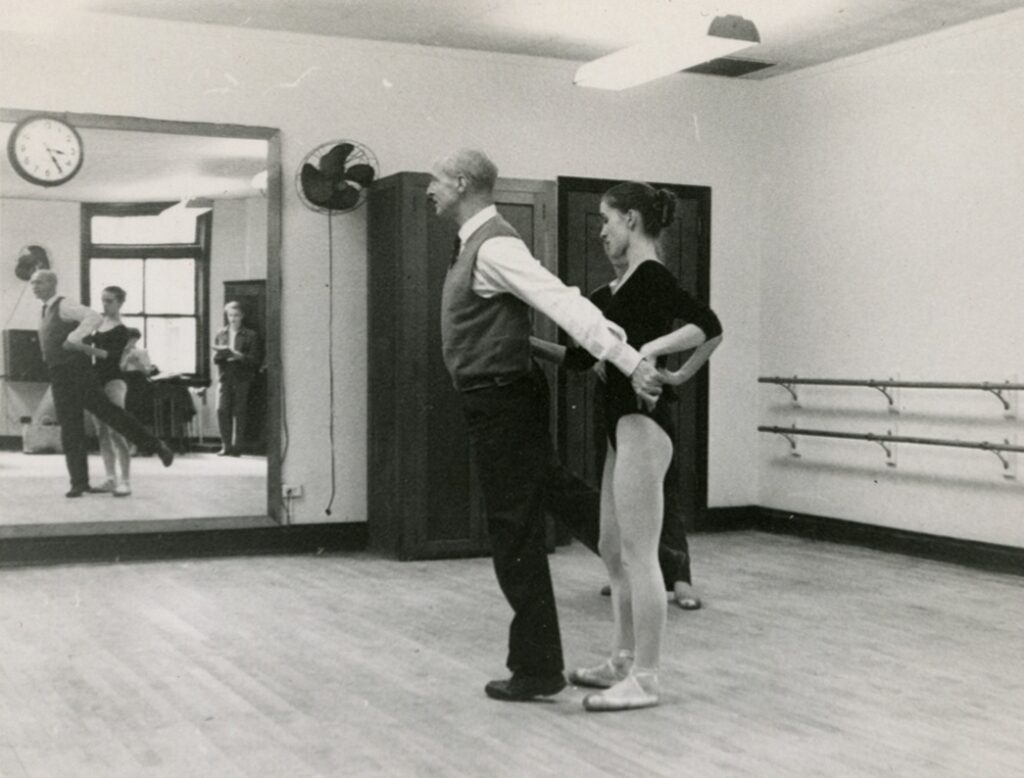

Antony Tudor rehearsing A Choreographer Comments with Koert Stuyf and Pina Bausch. Dance Division Scrapbook #4 (1959/60), p. 27. Photographer unknown.

But this film reveals that all the women students were weak on pointe. Knowing that Tudor choreographed the piece specifically for the students, I question the soundness of his decision to put them on toe before they were ready. I wonder if he even consulted with Margaret Craske, who taught pointe class.

It’s also no secret that Tudor could humiliate students. He had a knack for making cutting comments, ostensibly to toughen them up. He had nicknames for some of his students, and Bausch recalled that he had chosen a rather harsh one for her:

In the men’s class he simply called me Adolf and I had to come to terms with that. It was somehow quite clear. I had to take it. He knew that I liked him and I knew that he liked me so the German problem was settled between us…He called me Adolf. I was then Adolf. Adolf stood in the row.[26]

I was so confounded by this choice of nickname that I asked three people about it and got three different interpretations. When I told Rina Schenfeld, at first she was horrified. But after reading Pina’s full passage, she wrote this in an email to me:

It was for her [Pina] the answer about her guilt complex being German and me being an Israeli. Now I do understand. It was all there but in silence, the way my family were silenced about their family [members] being murdered by the Nazis. Nobody talked, [there was] only silence, and Tudor raised this up in a joke in a funny way, like trying to exorcise her guilt.[27]

Lance Westergard, who had been a favorite of Tudor’s at Juilliard and the Metropolitan Opera, explained to me that Tudor insisted on honesty onstage, and poking fun at young dancers was part of his commitment to that goal.[28]

Former dancer Judith Chazin-Bennahum, author of The Ballets of Antony Tudor, tended to chalk it up to a compulsive urge to insult: “He was a very cruel guy. He was not only intimidating; he could scorch you.”[29] But in a later email, she tried to square it with his larger mission: “I suspect he was trying to wake up the rather numb quality in the ballet person at the time. We were so used to doing whatever we were told, he tried to snap us into thinking about what we were doing.”[30]

In Sweden, one of Tudor’s students, Gerd Andersson (sister of the actress Bibi Andersson), had figured this out in a similar way to Bausch: For her, Tudor was “a mixture of kindness, sarcasm, and seriousness…You had to make a personal choice whether to take a joke positively or negatively. Whatever the difficulties, we all knew that what we got back far exceeded them.”[31]

Clearly the teenage Pina could take whatever darts were thrown at her. Tudor’s toxic name-calling did not put a dent in her admiration for him. She later told an interviewer, “There was a reason if he was rude. He believed if people were too comfortable they couldn’t dance.”[32]

Bausch engaged in his work even after she returned to Germany. In 1962, he came to the Folkwang Ballet in Essen to stage Lilac Garden and she danced the role of Caroline.[33] And she played the Old Woman in the production of The Green Table that was filmed by the BBC in 1967. She was also once cast as the lady with the feather boa in his Judgment of Paris (1938–40)[34] (though I haven’t found out where or when). This satirical ballet surely influenced her; at least this was the opinion of New York Times critic Anna Kisselgoff, who perceived, in a section of Bausch’s work Viktor (1986), a tribute to Judgment of Paris. Just as Tudor portrayed three over-the-hill women entertainers trying to interest one man, Bausch, in Viktor, choreographed three waitresses serving one male customer.[35]

Tudor, Sure. But La Meri—What a Surprise!

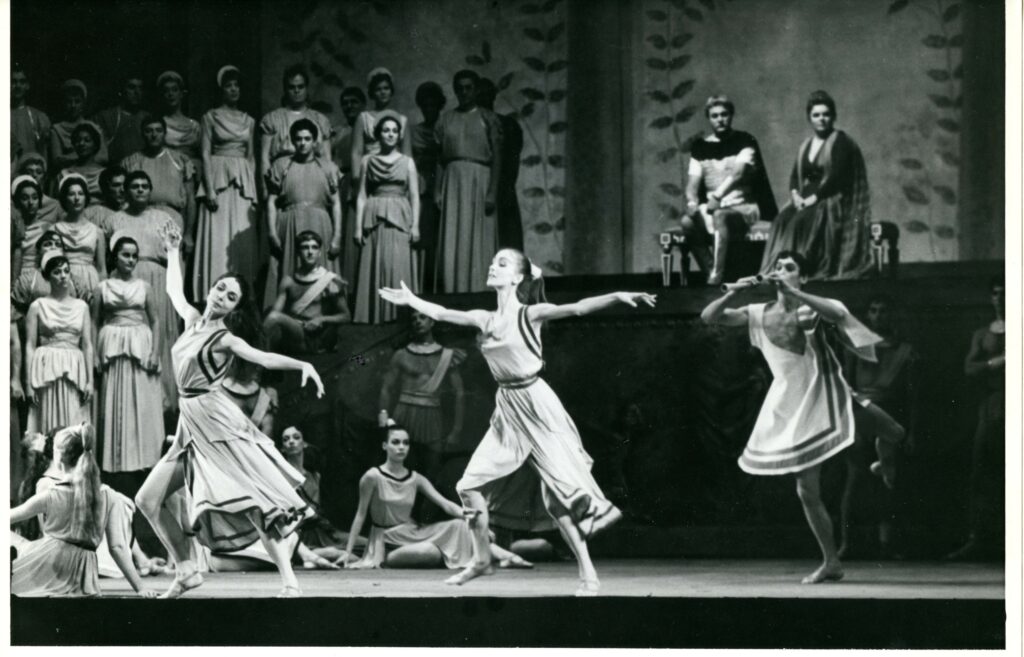

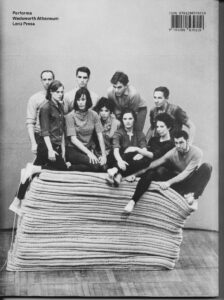

The concert of the Juilliard Dance Ensemble at the end of the 1959-60 school year comprised two programs: one in modern dance and one in ballet. The first, directed by Limón, was devoted to works by himself, Ruth Currier, and Doris Humphrey. Because Humphrey had died the previous December, Limón restaged Passacaglia and Fugue in C Minor (1938) in tribute to her. Pina and Chester Wolenski, a visiting guest alum, were cast in the lead roles originally danced by Humphrey and Charles Weidman. One of the few Humphrey works that enjoyed a long life, Passacaglia is known for its arcing body shapes, architectural formations, relationship of individual to group, and noble vision of humanity. The Juilliard archive has photos, but unfortunately no film.

Juilliard Dance Ensemble in Doris Humphrey’s Passacaglia. Bausch in center with angled elbows; Schenfeld second from right; to her right is Steve Paxton (!) To her left (far right) is Alice Condodina. Photo © Impact Photos, courtesy of the Juilliard Archives.

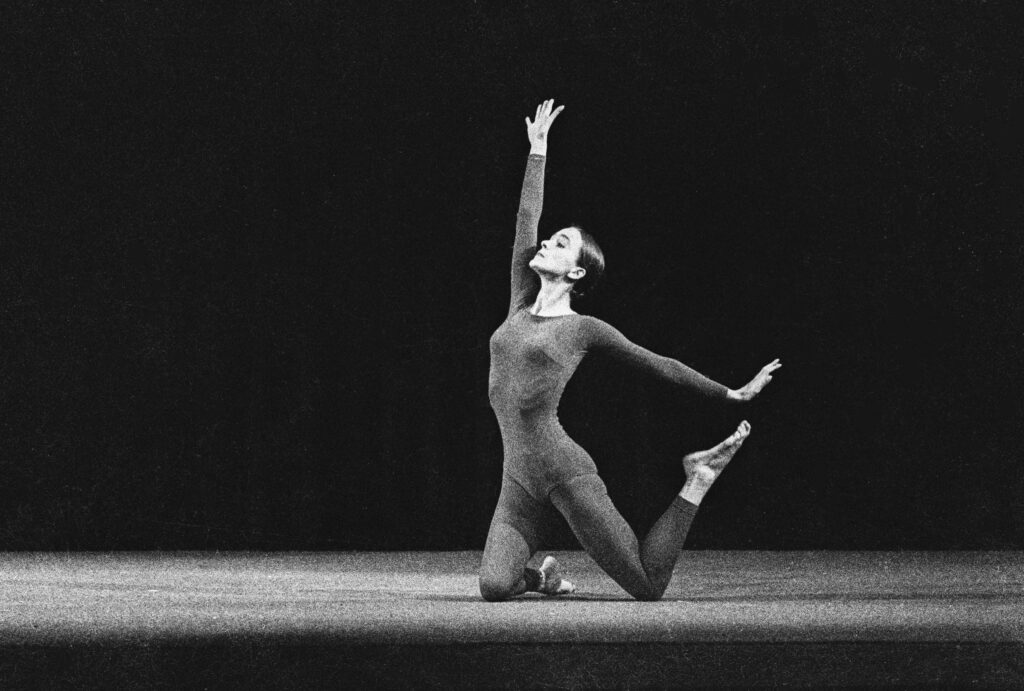

The ballet program, directed by Tudor, included two reconstructions of works from the Baroque era, two works by Tudor, and one by La Meri. Pina danced lead roles in Tudor’s A Choreographer Comments and La Meri’s The Seasons, both of which were documented by a special afternoon filming in a light-filled studio, thanks to Martha Hill’s prescience.

As a current member of the Juilliard faculty, I have access to these digitized films. I offer descriptions simply because I felt privileged to witness Bausch’s dancing at a young age.[36] I am not contending that these particular works were transformative for her, but perhaps they helped build a foundation she could later break away from.

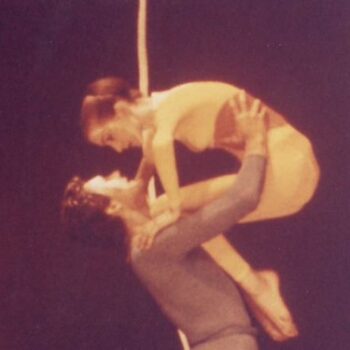

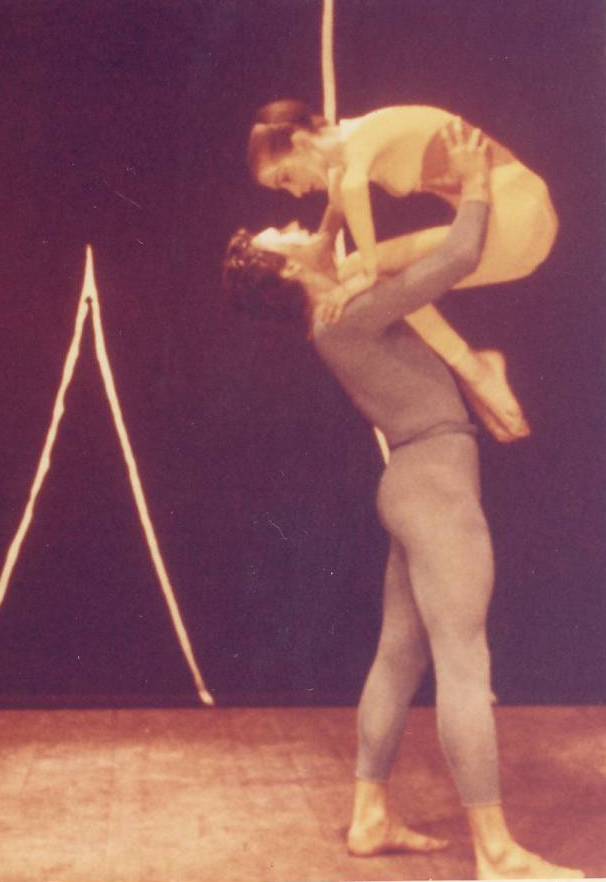

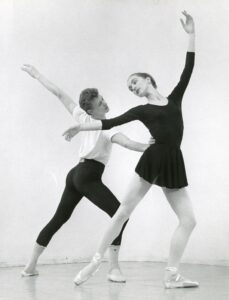

Bausch and Koert Stuyf in Tudor’s A Choreographer Comments, Photo © Impact Photos Inc., courtesy of the Juilliard Archives.

A Choreographer Comments had ten sections, each one demonstrating a different ballet step. The first, “587 Arabesques,” starts with Pina standing alone, her left foot crossed over the right ankle. In many lyrical but restrained forays, six women step into arabesque with three men intermittently supporting them. The section ends with Pina standing in exactly the same position she started in, left foot crossed over right ankle, but now she is enfolded in an embrace by Dutch student Koert Stuyf.

Pina is livelier in the third section, a duet titled “Pas de Bourrée.” She partners Stuyf in what dance historian Selma Jeanne Cohen called a “snidely priggish exposition” of this little connecting step.[37] Pina’s footgear is now low heels, so she doesn’t have to worry about pointework. She holds her chin up as though looking at the world in disdain, but this haughty look could be just from trying to keep her hat, perched far back on her head, from falling off. At one point, the woman and man bump into each other, back to back, and she turns and gives him a mild nod. Tudor told an interviewer that he turned Pina “into a comedienne” during the making of this ballet.[38] I wonder if he was referring to this barely noticeable moment. It all seemed tame to my eye.

As Walter Terry pointed out in the Herald Tribune, Tudor’s Little Improvisations was more appealing. He called it “an enchanting duet, at times playful, occasionally ironic, again tender and touching.”[39] While he commended the first cast, Mercedes Ellington and William Louther, one wishes he had also seen the second cast, with Bausch. There’s a moment in the choreography when the young woman is cradling a scarf as though it’s a baby and the cloth falls to the floor. When Schenfeld described Pina performing this “sad but beautiful duet,” she felt that it caught something about Pina’s own lingering sense of loss.

In contrast to the pristine A Choreographer Comments, the tender Little Improvisations, and the massive Passacaglia, La Meri brought a very different flavor to the concert. A dance artist in the tradition of Ruth St. Denis, La Meri traveled to Asia, Latin America, and Europe to learn traditional dances that she performed and taught at Jacob’s Pillow. (For some, this might raise a red flag for cultural appropriation, but Nancy Wozny voices a more complex view in Dance Magazine.) Tudor had seen The Seasons when it premiered at Jacob’s Pillow in 1953 and was so impressed that he brought it to Juilliard. La Meri used motifs from Bharatanatyam and other classical Indian forms, for instance the lotus with fingertips floating upward, the sprinkling of seeds with fingertips dipping downward, the elbow pulling back to indicate archery. The “Primavera” section featured images of “birds, streams, storms, children, and a dreaming shepherdess.”[40] All these images illuminated Vivaldi’s Four Seasons with verve and imagination — and Pina was absolutely magisterial in it.

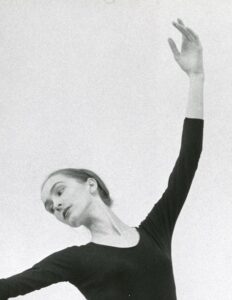

As seen in the archival film, Bausch’s long neck and sculpted face give her a startling elegance. She creates space and light around her upper body. In the slow duet with Carl Wolz [3], subtitled “Largo: The Plants Grow and the Cowherd Dreams,” she is grounded and regal, as though she herself were rooted in the soil, ready to grow. Her focus on the hands forming lotus blossoms is transcendent. In a later section, “L’Autumno: Adagio Molto: The Drunkards Dreams after the Grape Harvest,” she dances a languid, audaciously sensual, hip-swaying solo with a veil over her face and shoulders. Reviewing for Dance Magazine, Doris Hering wrote that one of two “especially exciting” sections was a “melting solo for Philippine Bausch.”[41]

I found this 18-year-old dancing on film to be astonishing in her artistry.

Plunging into the Darkness of Sanasardo and Feuer

Tudor knew that Pina wanted to dance more, and he had a hunch that she would be right for the work of Paul Sanasardo and Donya Feuer. Sanasardo had danced with Anna Sokolow, and Feuer had attended Juilliard a few years earlier. Their partnership was sparked by Feuer seeing Sanasardo in the original production of Sokolow’s Rooms (1955), that iconic drama of urban alienation. The two shared a three-floor loft in Chelsea—for only $250 a month![42] Called the Studio for Dance, the space became the hub of a highly theatrical form of dance exploration, a place where dancers dug deep into the human psyche. As dance scholar Mark Franko has written about their approach, “Intensity is indeed a crossing of the threshold in that it can confront us with ‘untamed’ areas of experience.”[43]

Sanasardo was teaching a rigorous modern dance class in his studio, and Tudor sent her to try it out. “She [Pina] came and took the class,” Sanasardo recalled. “She was gorgeous. She just decided we were going to work together.”[44] From Pina’s point of view, although she was still a student at Juilliard, the decision was a non-decision: “They talked to me. I couldn’t understand English, but I understood they wanted me to come to their studio. A lot of things just happened to me. I was also amazed—it was so new to me—that they had such late classes, that many people came, and the rehearsals that we did were at night. They took care of me. I never went home. I was kind of like in the family.”[45]

That she was “amazed” by people showing up at night reveals something about schedule. As mentioned by Nadine Meisner, on Bausch’s return to Essen she “found the pace in Germany lax.”[46] At both Juilliard and the Studio for Dance, classes and rehearsals had been nearly constant.

Sanasardo confirmed that “She more or less moved in.”[47] There was a daybed she could sleep on any time, so she didn’t have to travel back uptown.[48] Although Pina felt comfortable downtown, Feuer noticed that she “was very shy and cried a lot.”[49]

Sanasardo liked that Pina was a searcher: “She questioned a lot. And we used to talk a lot about, What was theater? Our early pieces were very concerned with breaking that boundary between dance and theater.” He also said, “She was spiritual. You saw her interior when she danced.” [51]

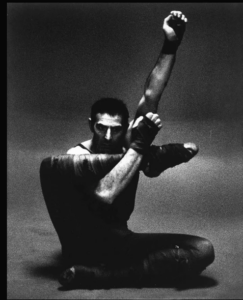

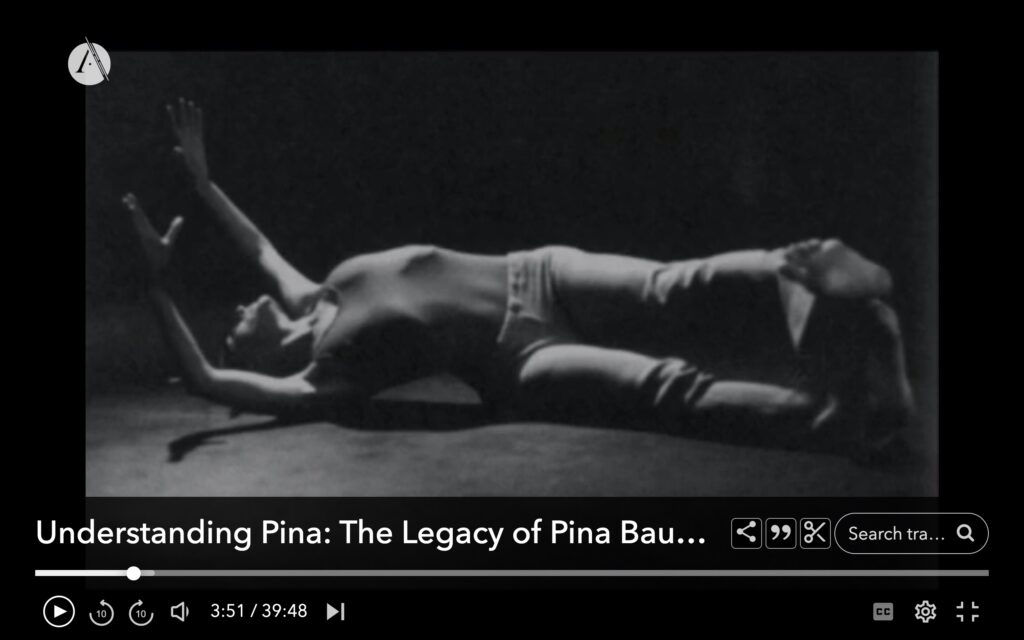

Sanasardo’s work, with its extreme character portrayals, had as much an affinity for theater as for dance. He himself was a strong, expressionist performer who, according Doris Hering, could look “simultaneously evil and heroic.”[52] His choreography was equally intense. Mark Franko wrote that “Studio for Dance productions were personal and poetic, as well as provocative and disturbing.”[53] Sanasardo and Feuer worked together from 1955 to 1963, when Feuer moved to Sweden. (She collaborated closely with filmmaker Ingmar Bergman.) The only time Sanasardo and Feuer collaborated with a third dancer was for Phases of Madness—and that person was Pina Bausch.

Franko writes that the basis of Phases was “the idea that certain behaviors exceed the bounds of rationality and are most readily conveyed by dancing.”[54] About both Phases and its successor, Laughter After All, Sanasardo recalled, “There was a lot of violence in those ballets.” He drew a direct line of influence, saying, “You see it in Pina’s work.”

Franko’s description of Laughter reveals a twisted brutality in which laughter was equated with screaming, and a maniacal doctor (played by Sanasardo) tortured innocent people. Yet Feuer and others have extolled the freedom they felt at the Studio for Dance. Franko suggests that both Phases and Laughter (which was made after Pina returned to Germany) illuminate “the dialectic between madness and freedom.”[55]

This, to me, is a key connection to Bausch’s early work. The first piece for her Wuppertal company, Fritz, played on this dialectic. Bausch herself played the part of a monstrous, ungainly Grandmother. The following is a description by Josephine Ann Endicott, an unforgettably ferocious performer in Tanztheater Wuppertal:

Fritz seemed to me to be a kind of nightmare with figures out of Pina’s childhood… An extremely pale woman with a bald head, a small creepy looking woman wearing a wig with hairs on her chin, a stiff, tallish woman in a deep lilac chiffon dress with incredibly long wooden arms…a headless man in a heavy, dark winter coat, a male in a one-piece nude bodysuit wearing high stiletto shoes, false bosoms and tied around his waist a huge red pair of lips. In the silence, you could hear coughing, buzzing, panting and breathing sounds…“Father” unbuttoned “Mother’s” many-buttoned dress. She buttoned up afterward. He pushed her face forcefully into a white enamel washbowl. Grandma – all grey and old in an ugly, long, colourless dress – sat hunched in her armchair. Her legs lay over a dancer’s shoulders, which were hidden by her dress so that when she stood up she became gigantic. Pina played this part.[56]

These characters could almost have come out of a Sanasardo/Feuer production.

Many critics have described Pina Bausch’s darkness or obsessiveness as typically Germanic, but clearly Sanasardo and Feuer’s encouragement to explore the dark, bizarre side of the imagination was a key that opened inner doors for her.

Sokolow, who taught at Juilliard (mostly in the drama division), was also a potent influence. Sanasardo told me that Bausch loved Sokolow’s Rooms. While Rooms projected a bleak vision of humanity, it also brought forth vividly individual characterizations from the dancers. Ann Daly goes so far as to say that Rooms foreshadowed Bausch’s form of tanztheater.[57] While I think Rooms is too earnest, too lacking in irony, to be considered a precursor to Bausch’s work, I do agree that the portrayal of the societal harshness of Rooms could have struck a chord in Bausch.

Having been in the original cast of Rooms, Sanasardo said to me, “Of course Pina had a dark edge, which was very German Expressionist. I had a dark edge.”[58] In his work Pain (1971), he displayed his suffering lavishly. Meredith Palmer in the Harvard Crimson wrote:

With bound feet and shackled hands, lead dancer Sanasardo writhes chained to a bar, often assuming Christ-like positions, while the company screams, beats heels on the floor and squirms in sympathetic reaction. The horror of Sanasardo, knocking his head on the floor as he crosses the stage, causes gritted teeth and stifled cries in the audience.[59]

One might say that Sanasardo took Sokolow’s darkness to further extremes. Anna Kisselgoff put it succinctly: “No one leaves a Sanasardo concert laughing.”[60] Doris Hering described one section of Laughter After All in Dance Magazine: “Paul Sanasardo whacked Donya Feuer on the head,” and “she sank away from the impact, only to crawl back doggedly.”[61] That description of obsessiveness infused with masochism may sound familiar to Bausch-watchers.

Poster for performance at the Y, Dec. 1959; Woodcut by Isidor (Frank) Canner. Courtesy Pina Bausch Fndn.

Another Sanasardo/Feuer work that affected Bausch was the full-length In View of God: An Unspoken Drama in Three Acts (1959), in which Bausch performed the role of Mother, replacing Cynthia Steele. In View of God featured the remarkably solemn presence of eleven children as witnesses to erratic adult behavior. Reviewer Walter Sorell found the work frustrating but wrote that the dancers “set a morbid mood and, as they went along, achieved some stunning images that had color, poetry and inner drama.”[62]

About the children’s performance, Bausch commented, “There was nothing childish. There were like adults, only very young ones: young human beings. There was nothing cute. It was very simple.”[63] Fast forward to Bausch’s 2009 experiment of teaching the sexually combative Kontakthof to teenagers, captured in the documentary film Dancing Dreams, I’m reminded of her long-ago witnessing the self-possessed children of the Studio for Dance.

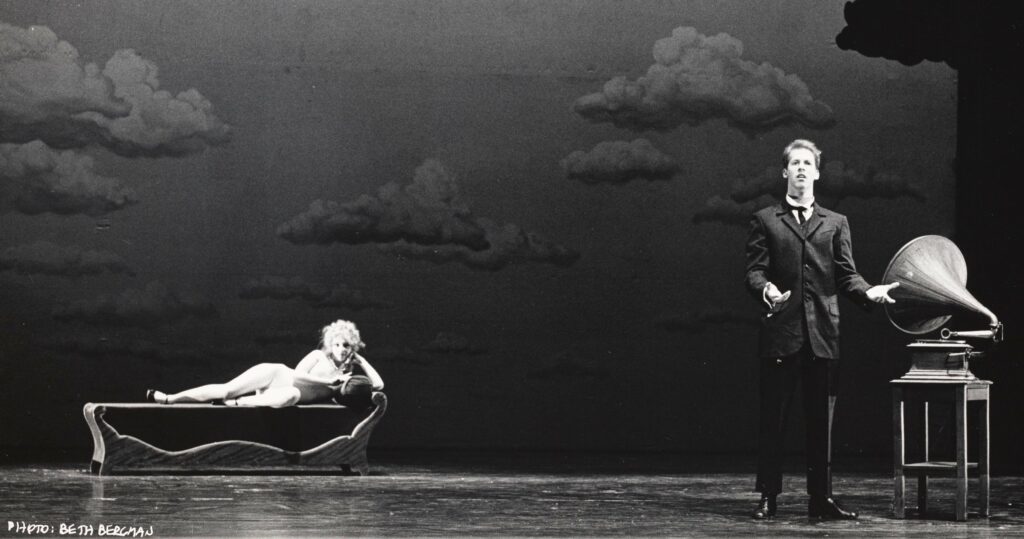

Critic Marcia B. Siegel believes that Bausch’s work resembles that of Anna Sokolow more than any other dance artist. I don’t know if Siegel was aware that Bausch had absorbed Sokolow’s aesthetic through Sanasardo. In 1986, Siegel wrote, “A Sokolow dance is a series of escalating and subsiding shocks powered by the ongoing, repetitive drive of constant motor activity, a direct expression of feeling carried to an extreme.”[64]

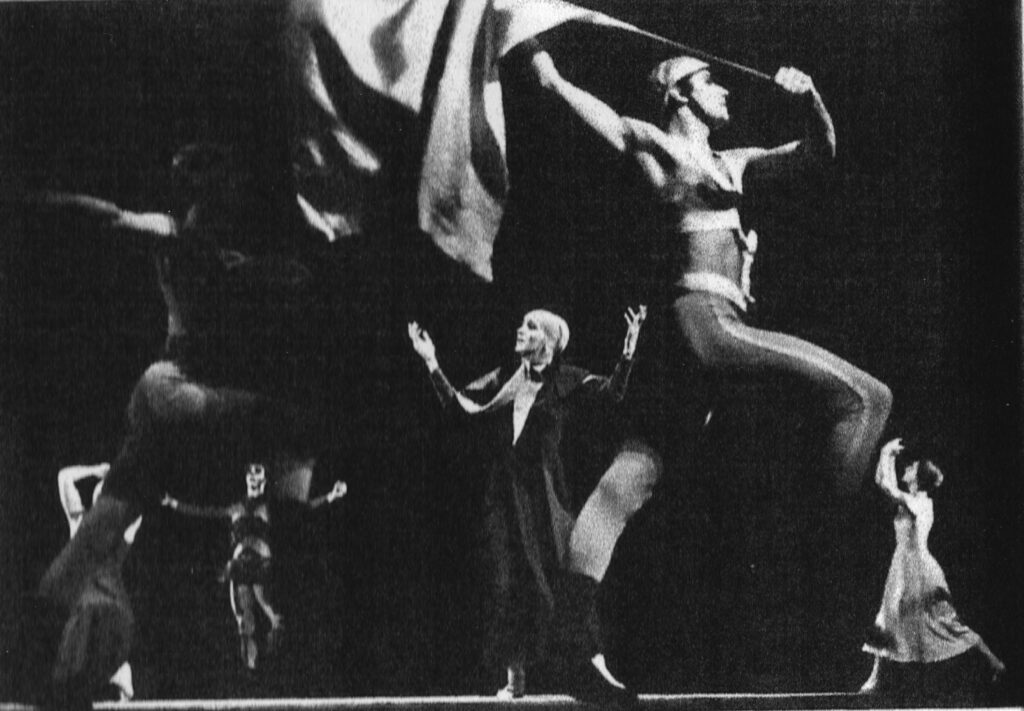

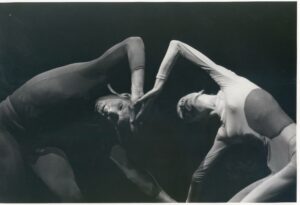

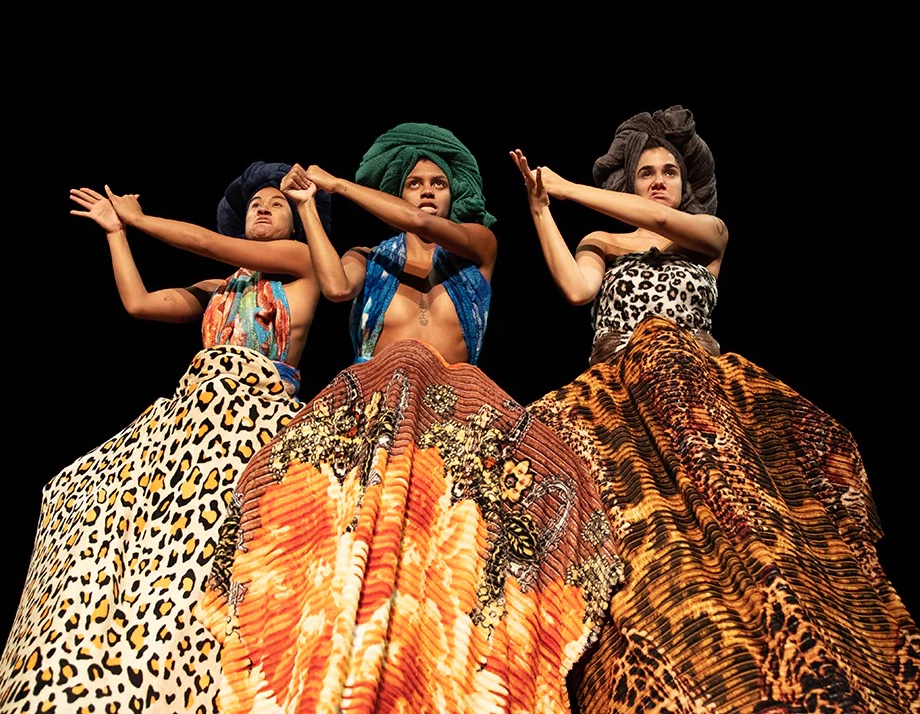

Magritte, Magritte by Anna Sokolow, with Juilliard students, photo © Beth Bergman, courtesy of the Juilliard Archives.

But Sokolow also possessed another, very different quality that captivated Bausch. Jim May, longtime Sokolow dancer and founder of the posthumous company, recalled Bausch’s reaction to the American choreographer’s Magritte, Magritte (1980), her tribute to the surrealist painter:

After the premiere of Magritte, Magritte the Sokolow Player’s Project went on an extensive European tour which included a performance at the Cologne Opera House where we presented Magritte. After the performance an excited Pina Bausch came running backstage… She came up to Anna and said, “Anna this is exactly what I want to do!”[65]

It seems to me that Bausch combined Sanasardo’s darkly obsessive quality and the surreal, dreamlike sensibility of Sokolow’s Magritte, Magritte—as well as other influences—into a style that was thought-provoking, absurdist, sometimes funny—or something like funny—while keeping a sharp psychological edge.

Needless to say, Jooss was a major part of Baush’s lineage, and she undoubtedly possessed what one critic called “Bausch’s ineradicable Germanness.”[66] But Sanasardo and Sokolow were also prominent threads in the tapestry of her sources.

Spoleto, June 1960

After the year-end concert at Juilliard in the spring of 1960, Pina headed for the Festival of Two Worlds in Spoleto, Italy, as a dancer with Paul Taylor. That summer Gian Carlo Menotti conceived a new (short-lived) company called New American Ballets that would perform both ballet and modern dance works. (I suspect that Menotti was trying to recreate the spectacular success of Jerome Robbins’ Ballets USA during the first summer of his festival in 1958.) The choreographers were Donald McKayle, Karel Shook (later to co-found Dance Theatre of Harlem with Arthur Mitchell), Herbert Ross, and Taylor. The company included Mabel Robinson, Dudley Williams, and Graham dancer Akiko Kanda (all of whom had been Pina’s classmates at Juilliard), as well as Mary Hinkson, and Arthur Mitchell—who was tasked by Menotti to organize the group. Bausch was able to continue her friendship with Mabel Robinson that she’d had at Juilliard.

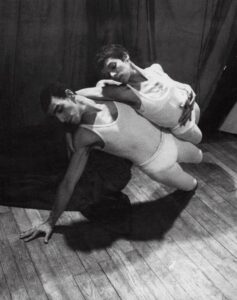

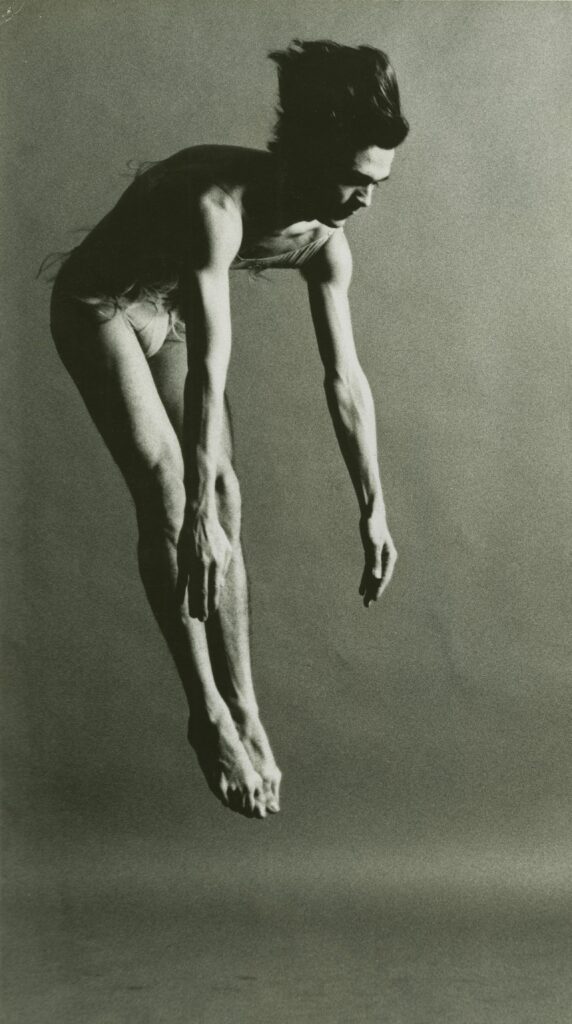

Taylor was making a new duet for Bausch and Dan Wagoner (on leave from the Graham company) that was half of a quartet titled Tablet. In his autobiography, Taylor wrote that he was inspired by Bausch:

Pina…one of the thinnest human beings I’ve ever seen… is able to streak across the floor sharply, though a bit unevenly, like calipers across paper. She’s also able to move slower than a clogged up bicycle pump; I love watching her and suddenly have an idea for the duet—am eager to turn her into a black widow spider or praying mantis.”[67]

McKayle had a vivid memory of Bausch in Tablet:

Paul took advantage of Pina’s wafer-thin physique, clothing her in a white body suit and painting her face white except for a circle of orange encasing her eyes, nose, and lips [costume by Ellsworth Kelly]. When the lights came up on the motionless Bausch, there was a gasp from the audience and a woman’s voice spoke aloud, “Guarda la morte!” (Look at death!)… With her head tilted slightly to the side, the bones at the back of her neck glistened in pristine white, and a ghostly apparition took shape as she became la morte, the personification of death.[68]

Despite the ghastly, ghostly look, the public adored Bausch, along with the other two female leads of the company: Mary Hinkson (who had been one of Pina’s favorite teachers at Juilliard) and Akiko Kanda. McKayle writes that the three “were suddenly stars.”[69]

Wagoner, Bausch, Taylor and Konda in Taylor’s Tablet, Costumes and sets by Ellsworth Kelly, photo courtesy PTDC

Nevertheless, she grew homesick—whether for New York or Germany, Taylor did not know—and he, like Feuer, noticed that she often cried. It seems that melancholy was part of who she was.

Working with Taylor, Bausch learned a more subtle possibility in terms of subject matter. According to Isa Partsch-Bergsohn, “She liked his choreographic style very much. Paul Taylor did not state his subject matter, but implied the meaning in his choreography.” [70] His approach allowed her to edge away from an obviously stated theme and go toward greater ambiguity.

It’s worth noting, too, that McKayle’s Games (1951) was also on the Spoleto program. Since Pina’s close friend Mabel was in the cast, Pina likely saw it that summer. Games involved dancers playing children’s games as though outdoors on the street, and of course much of Bausch’s work involves game-like playing.

The Metropolitan Opera Ballet

Pina loved New York and wanted to stay on after her year at Juilliard was over. Tudor knew this, so he offered her a job dancing with the Metropolitan Opera Ballet, where he was director. Company class was given by the same three ballet teachers who taught at Juilliard: Tudor, Corvino, and Margaret Craske. Chazin-Bennahum, who was also in the Met Opera Ballet at the time, recalled the rigor of Tudor’s technique sessions:

His classes were brutal. They were choreographic artworks: He would have you turning one direction, right away turning in the other direction. They were terribly difficult, really really tough. Anybody who worked with Tudor had to pick up like that [snaps fingers].[71]

Between the fall of 1960 and the spring of 1961, Bausch performed in five operas, about eight performances each. She had featured roles in Alceste and Tannhauser, and was in the corps in Carmen, Turandot, and La Gioconda.[72] The old Met stage on Broadway at 39th Street was 86′ by 101′, no doubt bigger than anything Pina had encountered. As Chazin-Bennahum told me, there could be more than a hundred singers and dancers onstage, and even more musicians in the orchestra pit. Pina loved hearing the singers’ voices from backstage, “to learn to distinguish between voices. To listen very exactly.”[74]

Dancing with the Met Opera also gave her a chance to continuing taking class with Corvino, who was, like Hoving, a link between Folkwang and Juilliard. A ballet teacher at Juilliard for many years, he had also toured with Kurt Jooss’s company and had taught in Essen. Like Jooss, Corvino felt that ballet and modern dance could live in harmony in the training.”[75] Corvino taught body mechanics with a sense of harmony, generosity, and buoyancy. His daughter Ernesta, who took over some of his classes after he died, said, “He really understood the body in motion, the body in function; it wasn’t just about a certain balletic aesthetic.”[76] His presence was grounding and calming and full of wonder. Dawn Lille, Corvino’s biographer, felt he had “an almost childlike openness.” Developing sensitive feet, expressive hands, and a sense of weight was a central part of his approach. When he retired from Juilliard in 1994, Bausch invited him to Wuppertal to give company class. For the next decade, the elderly Corvino spent about six months a year touring with her company.[77]

Pina made an impression on the other dancers: Chazin-Bennahum remembers her “aristocratic look.” Bruce Marks compared her to the great Balanchine ballerina Tanaquil LeClercq: “Pina was a young modern version of Tanny, she had a spider-like feeling. She was fascinating to watch. She was a creature.”[73]

Dancing in New York widened the range of music Bausch was exposed to. At the Met, she danced to the operatic music of Wagner, Gluck, Bizet, Purcell. In her composition classes at Juilliard, her fellow students used Schoenberg, Scriabin, Bartok, Debussy, Satie, and jazz composer Mose Allison. Sanasardo sometimes used jazz music also. She had gained a sense of freedom as to her choices while living, working, and listening in New York. As Norbert Servos writes in his online biography, “The distinction between ‘serious’ and ‘popular’ music, still firmly upheld in Germany, was of no significance to her. All music was afforded the same value, as long as it expressed genuine emotions.”[78]

Called Back to Essen

When Jooss invited Bausch to join his reconstituted Jooss Ballet in 1961, she felt torn:

After two years [in NYC] came a phone call from Kurt Jooss. He had the chance again to have another small ensemble at the school, the Folkwang Ballet. He needed me and asked me to come back. At the time I was wrestling with a great conflict between the desire to stay on in America, and the dream of being allowed to dance in Jooss’s choreographies. I wanted both of these things so much. I loved it so much being in New York; everything was going wonderfully well for me. However, I returned to Essen after all.[79]

So Bausch went back home to work with her mentor. She danced with the Folkwang Ballet (later called Folkwang Tanzstudio) as a soloist and assistant to Jooss.

But there’s another story about her return to Germany. Paul Sanasardo remembers it this way:

Pina got very, very thin, she was a little bit anorexic. We all got very concerned. We didn’t know quite what to do. I couldn’t act like her dogmatic father and tell her what to do…So I called Lucas Hoving, who I knew knew Jooss, and she was Jooss’s protégée. He came and looked at her and said, “Ohhh,” and he arranged for her to get back to Germany.[80]

According to John O’Mahony, writing in The Guardian, Pina did not conquer the eating disorder until Jooss gave her an ultimatum to gain weight or leave his company.[81]

In her Kyoto speech, Bausch talked about her eating habits as an eccentricity or as a way to save money, to stretch the one-year grant over two years. But she goes deeper to something that is spiritual:

However, I liked getting thinner. I paid more and more attention to the voice within me. To my movement. I had the feeling that something was becoming purer and purer, deeper and deeper. Perhaps it was all in the mind. But a transformation was taking place. Not only with my body.[82]

I felt that I witnessed that purity while watching the documentary film of Bausch in La Meri’s The Seasons. She danced the essence of spring, of a gradual blossoming. There was nothing extra. Her inner radiance shone through.

Back and Forth Between Germany and the U. S.

Bausch has said that Kurt Jooss was like a second father.[83] Similarly, Martha Hill at Juilliard may have been like a second mother—a role she played to many young hopefuls. After Pina returned to Germany in 1961, she sent Hill a postcard assuring her that she was in good hands. She wrote that she loved New York but it was good to be home and working with Jooss.

Bausch began making dances at Folkwang Tanzstudio and soon became its leading choreographer. But she was pulled back to the States three times before taking the helm of Wuppertal Ballet Company in 1973. First, in 1968, she came to Jacob’s Pillow as the performing partner of French dancer Jean Cébron, who had been teaching at Folkwang School. Then in 1971, Lucas Hoving, who had a long association with Connecticut College Summer School of Dance (American Dance Festival), invited her to make her own solo within his new sextet, Zip Code. She titled it Philips 836 887 DSY.[84] In a review in Dance News, Frances Alenikoff described her as “a haunted, predatory creature stalking in deep crouches, spiralling turns, and angled, disjointed poses.” Doris Hering wrote in Dance Magazine that Bausch “stretched and curved like a mythological serpent, more beautiful than fearsome.”[85]

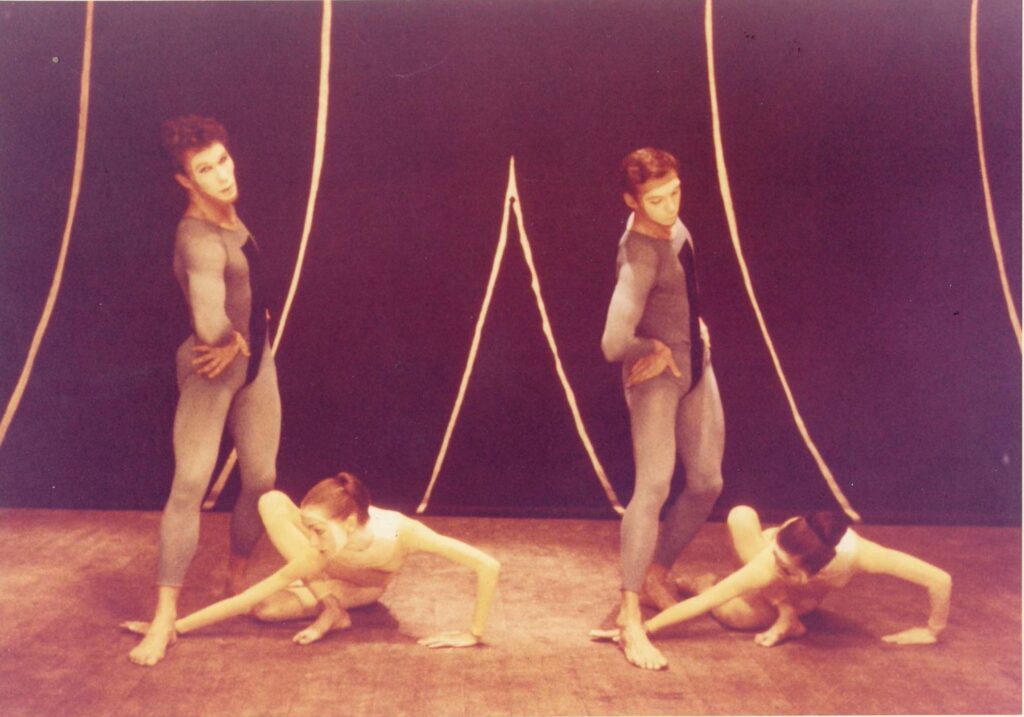

Screen grab of Bausch in solo at Saratoga, from the documentary “Understanding Pina,” dir. Kathryn Sullivan.

Third and most fateful, was the following summer, when Bausch was a guest artist in Sanasardo’s company for its four-week residency at Saratoga Performing Arts Center in upstate New York. She staged her piece Nachnull (Afterzero) (1970) for the women of his company. But it was again her solo, Philips 836887 DSY, that captivated the critics. Dance Magazine reviewer Judy Kahn wrote the following:

The highlight of the concert was German guest artist Pina Bausch. Her body designs contort in snake-pulling movements, travelling from large patterns to their smaller, more intricate extensions… choreographically unlike anything seen in this country. In her solo she releases her back in a knee-bent “S” and flexes her foot hard, peering at the audience with a poignant sense of humor and foreboding. Her creaturesque, humanoid forms hover in an abstract yet basic realm of human experience… communicating in images tucked away in the subconscious, in private dreams and public mythologies.[87]

Bausch’s solo was also the highlight for Dominique Mercy, who was dancing with Sanasardo that summer. In a 2018 interview, the French dancer recalled, “When she [Bausch] danced her solo performance I was completely in awe and felt…very close to it. I felt that it was something I belonged to. And I knew it was a very beautiful experience and we really connected.”[88]

That summer Bausch stayed in a house with Manuel Alum, the powerfully expressive protegé of Sanasardo who had started to choreograph on his own. Mercy and another French dancer, Marie-Louise (Malou) Airaudo, who had met Alum in France, were also staying in the house. All four became quite close, and when Bausch was hired to lead the Wuppertal company the following year, she asked Manuel, Dominique, and Malou to join her. The last two did. Dominique danced with the company until her death and beyond. Malou stayed with the company till the mid 90s, then taught in Folkwang.

Mercy, in particular, helped define the Bausch aesthetic. With his beguiling deadpan, he revealed the comic underbelly of her work without losing the choreographic precision. As Ann Daly put it, he “carries her sense of existential isolation, and humor.”[89] Scholar Marcelo de Andrade Pereira contends that Mercy’s long relationship with Bausch made it possible to keep her legacy alive in the four years after her death, when Mercy was co-directing the company.[90] And that relationship has its roots in the Sanasardo work.

After Saratoga, Bausch and Alum remained close friends. Also a “foreigner,” Alum was from Puerto Rico. In the 1970s and ’80s, Bausch stayed at his loft in Tribeca whenever her company performed at the Brooklyn Academy of Music.[91] Alum died of AIDS-related causes in 1993—one of many losses in the dance community.

Last Thoughts

The American impact on Bausch was more than a series of exposures to challenging or provocative work. It was an emotional impact, partly because she was young and impressionable. As she told an interviewer, “I have a big feeling of connection to New York. When I think about New York, then I have what I otherwise never feel, that is a feeling of home. Of homesickness. That’s quite strange.”[92] Strange because New York was neither Solingen, where she was born and danced with the Solingen’s Children’s Ballet, nor Essen, where she trained at the Folkwang School. But New York was where she grew up as an artist, where she grappled with big personalities and big ideas. Juilliard was (and is) a community of dance artists striving to find a balance between discipline and freedom. Juilliard was where she encountered Tudor, Limón, Corvino, Sokolow, La Meri, McKayle, Hinkson, and Horst. Her extra-curricular life introduced her to Sanasardo, Feuer, Alum, Mercy, Airaudo, and Taylor.

When Bausch started choreographing, she drew on her experiences in New York: Tudor’s psychological ballets; Sokolow’s cultivation of the vivid individual; Sanasardo’s and Feuer’s depiction of the obsessive soul. And of course, the cultural expansiveness she found in the Big Apple. I believe that the scope and depth of her oeuvre would not have been possible without those two years in New York— and the decisive residency at Saratoga a decade later.

I leave you with these words from Bausch. They are her acceptance speech upon receiving a Dance Magazine Award, December 8, 2008, only seven months before she died:

Ladies and Gentlemen,

I feel very moved to receive the Dance Magazine Award, 2008, in this city. What all happened to me in New York! All these incredible people I met and learned from. All these unforgettable memories which formed, influenced me forever. Especially, I thank Harvey Lichtenstein, who invited us at the very beginning, and of course the whole Brooklyn Academy family, Joe Mellilo, and not the least the wonderful New York audience.

When I was 18 years old, I was traveling all alone to America without being able to speak a word of English. My parents took me to the port of Cuxhaven. A brass band was playing as the ship was setting off, and everybody was crying. I went onto the ship and waved. My parents were also waving—and crying. And I was standing on the deck and crying too. It was terrible. I had the feeling we would never see each other again. Then I wrote a short letter to Lucas Hoving in New York and posted it on the way to Le Havre [sic]. Lucas has been one of the teachers in Folkwang School in Essen. I was very much hoping that he would pick me up in New York. Eight days later, when I arrived in New York, I didn’t have my health certificate in my bag, but it was in my suitcase. Therefore, I had to spend many hours on the ship waiting until the over thousand passengers had been dealt with. Finally, they took me to my suitcase. I no longer expected that Lucas would still be there, even if he had received my letter. Yet, when I walked off the ship thirteen hours later, he was still standing there. Hanging over his arm were flowers that had wilted in the meantime. Poor Lucas! He had been waiting for me all this time! This for me unforgettable memory shows how I was welcomed then, and how I feel welcomed each time I come to New York.

Thank you very much.[93]

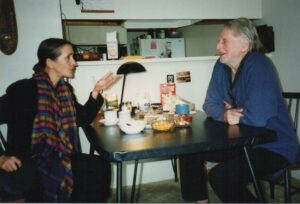

Bausch and Hoving, 2000, shortly before his death, Photos by Cheryl Yonker, courtesy Lucas Hoving Facebook page

§§§

Special thanks to Jeni Dahmus Farah, archivist of The Juilliard School. When she showed my dance history class a photo of Bausch with Tudor, she commented on how it revealed their close relationship. That led to my curiosity, which led to this research. Thanks also to Ismaël Dia, archivist of the Pina Bausch Foundation; Norton Owen, director of preservation at Jacob’s Pillow, and Laura Vroom at the Metropolitan Opera. Gratitude to everyone who agreed to be interviewed: Paul Sanasardo, Rina Schenfeld, Judith Chazin-Bennahum, Carla De Sola, Ernesta Corvino, Mercedes Ellington, Diane Germaine, Janet Mansfield Soares, Sylvia Waters, Bruce Marks, Judith Canner Moss, Janet Panetta, Lance Westergard, Alice Condodina, and Rosalind Newman. Much thanks to the Jerome Robbins Dance Division of the NY Public Library for the Performing Arts for inviting me to present a version of this paper in 2022 as an episode of “The Dance Historian Is In.” Thanks also to Tanz for publishing the German-language version in their August 2023 edition.

Notes

BIG APOLOGY for the numbers being out of order. But they do match up with the numbers in the text.

[50] Rina mentioned that Pina had a cousin in the Aco neighborhood of Tel Aviv, who revealed that her mother—Pina’s aunt—was Jewish. Schenfeld has written about this in her online “Letter to Pina Bausch,” in 2014. However the archivist of the Bausch Foundation has corrected this to say it was about her grandmother’s sister, not her mother’s sister.

[3] Wolz became the Dean at the Dance Program at the Hong Kong Academy of Performing Arts. He started and led the World Dance Organization until his death in 2002.

[5] She danced in two duets by Cébron. Ritha Devi and Company of Indian Musicians were also on the program. See Jacob’s Pillow Archives https://archives.jacobspillow.org/Detail/objects/4958

[1] Norbert Servos, “Talking about People through Dance—Pina Bausch Biography,” accessed November 2, 2022.

[5] Jay L. Kaplan, “Pina Bausch: Dancing Around the Issue,” Ballet Review, Spring 1987, 74–77; Susan Manning, “An American Perspective on Tanztheater,” TDR, Summer 1986, 57–79.

[6] Pina Bausch Online Archive, In View of God, 92nd Street Y, December 19, 1959.

[7] Meisner, 172.

[8] Quoted in Luke Jennings, “Pina Bausch: German choreographer whose bleak vision changed the face of European dance,” The Guardian, U.S. Edition, June 30, 2009. .

[9] Rina Schenfeld, Zoom interview with author, February 9, 2022.

[10] Sylvia Waters, phone interview with author, February 6, 2022.

[11] Carla De Sola, phone interview with author, November 28, 2021.

[12] Mercedes Ellington, phone interview with author, Dec. 22, 2021.

[13] Waters, phone interview.

[14] Pina Bausch, “What moves me,” 2007, on the occasion of receiving the Kyoto Prize, accessed February 2, 2022, published with permission the Inamori Foundation.

[15] Schenfeld, Zoom interview, February 9.

[16] Juilliard Dance Division Scrapbook, 1959/1960, 12, 23–25, 59–64, 71, 117.

=, accessed December 14, 2022.

[17] Mansfield Soares, email message to author, July 21, 2022.

[18] Mansfield Soares, email message to author, November 5, 2022.

[19] Quoted in Marion Meyer, Pina Bausch: dance, dance, otherwise we are lost, translated by Penny Black (London: Oberon Books, 2018), 20.

[20] Rita Felciano,“Pina Bausch Finds a Ray of Light,” Dance Magazine, November 2004, 34–40.

[21] Schenfeld, Zoom interview, February 9.

[22] Carla De Sola, phone interview and “Reminiscence,” Zoom panel of Juilliard alums, November 17, 2021.

[23] Quoted in Mark B. Bliss, ed. Antony Tudor Centennial (Antony Tudor Ballet Trust, 2010), 54.

[24] Schenfeld, Zoom interview, February 9.

[25] Quoted in Bliss, Antony Tudor Centennial, 53.

[26] Quoted in Bliss, Antony Tudor Centennial, 54.

[27] Schenfeld, email message to author, February 10, 2022.

[28] Lance Westergard, phone conversation with author, July 10, 2022.

[29] Judith Chazin-Bennahum, Zoom with author, March 3, 2022

[30] Judith Chazin-Bennahum, email message to author, July 11, 2022.

[31] Quoted in Donna Perlmutter, Shadowplay: The Life of Antony Tudor (New York: Viking, 1991), 270.

[32] Valerie Lawson, “Pina, queen of the deep,” The Pina Bausch Sourcebook, ed. Royd Climenhaga (London, Routledge, 2013), 221. Originally published in Sydney Morning Herald, July 17, 2000.

[33] Perlmutter, Shadowplay, 269.

[34] Bausch, “What moves me.”

[35] Kisselgoff, “Dance View: Pina Bausch Adds Humor to Her Palette,” New York Times, July 17, 1988.

[36] These documentary films are also available at the Jerome Robbins Dance Division of the NY Public Library for the Performing Arts, but they have not been digitized, so the image is slightly streaked with aging lines.

[37] Quoted in Judith Chazin-Bennahum, The Ballets of Antony Tudor: Studies in Psyche and Satire (New York: Oxford University Press, 1994), 189.

[38] Quoted in Chazin-Bennahum, 189.

[39] Walter Terry, “Juilliard Dance Series, NY Herald Tribune, April 11, 1960.

[40] Nancy Lee Chalfa Ruyter, La Meri and her Life in Dance: Performing the World (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2019), 189.

[41] Juilliard Dance Division Scrapbook, 1959/1960, 92. Originally Doris Hering, “Concert Reviews,” in Dance Magazine, June 1960, 20.

[42] Paul Sanasardo, phone call with author, July 17, 2022.

[43] Mark Franko, Excursion for Miracles: Paul Sanasardo, Donya Feuer and Studio for Dance (1955–1964) (Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2005), xviii.

[44] Sanasardo phone interview with author, December 26, 2021.

[45] Franko, Excursion, 2.

[46] Meisner, 168.

[47] Sanasardo, phone interview.

[48] Judith Canner Moss, email message to author, February 15, 2022.

[49] Quoted in Luke Jennings, “German choreographer whose bleak vision changed the face of European dance,” The Guardian, U.S. Edition, June 30, 2009.

[50] Rina mentioned that Pina had a cousin in the Aco neighborhood of Tel Aviv, who revealed that her mother—Pina’s aunt—was Jewish. Schenfeld has written about this in her online “Letter to Pina Bausch,” in 2014. However the archivist of the Bausch Foundation has corrected this to say it was about her grandmother’s sister, not her mother’s sister.

[51] Sanasardo, phone interview.

[52] Doris Hering, “A Darkening Pond: Paul Sanasardo Reviewed,” Dance Magazine, August 1971, 73-74.

[53] Franko, Excursion,10.

[54] Franko, Excursion, 7.

[55] Franko, Excursion, 134.

[56] Josephine Ann Endicott, “Dancing Back to Life: Dancing For Pina: The Days and Years of My Life With Tanztheater,” unpublished manuscript.

[57] Ann Daly, “Remembered Gesture,” Critical Gestures: Writing on Dance and Culture (Middletown: Wesleyan University Press, 2002), 28.

[58] Sanasardo, phone interview.

[59] Meredith A. Palmer, “Paul Sanasardo Dance Company,” The Harvard Crimson, October 12, 1971, accessed November 21, 2022.

[60] Anna Kisselgoff, “Dance: Sanasardo Group,” New York Times, April 28, 1973.

[61] Doris Hering, “Paul Sanasardo and Donya Feuer in ‘Laughter After All,’ ” Dance Magazine, August, 1960, 24.

[62] Walter Sorell, “In View of God, a dance in three parts by Paul Sanasardo and Donya Feuer,” Dance Magazine, June, 1959.

[63] Franko, Excursion, 65.

[64] Marcia B. Siegel, “Carabosse in a Cocktail Dress,” The Hudson Review, Spring, 1986.

[65] Email message from Jim May to Samantha Geracht, forwarded to author, March 3, 2022.

[66] Johannes Birringer, “Pina Bausch: Dancing Across Borders,” TDR, Summer 1986, 85–97.

[67] Taylor, Private Domain, An Autobiography (San Francisco: North Point Press, 1988), 97.

[68] Donald McKayle, Transcending Boundaries: My Dancing Life (London: Routledge, 2002), 128.

[69] McKayle, Transcending, 129.

[70] Isa Partsch-Bergsohn, “Dance Theatre from Rudolph Laban to Pina Bausch,” The Pina Bausch Sourcebook, ed. Royd Climenhaga (London: Routledge, 2013),16. Originally published in Dance Theatre Journal, October, 1987.

[71] Judith Chazin-Bennahum, Zoom interview with the author, March 3, 2022.

[72] Metopera Database, the online archive of the Metropolitan Opera Guild, accessed March 2, 2022 and follow-up emails with Laura Vroom, assistant archivist.

[73] Bruce Marks, phone interview with the author, December 23, 2021.

[74] Bausch, “What moves me.”

[75] Dawn Lille, Equipose: The Life and Work of Alfredo Corvino (New York: Dance Movement Press, 2010), 136.

[76] Ernesta Corvino, phone interview with the author, July 11, 2022.

[77] Lille, Equipose, 119–121.

[78] Servos, “Talking about People.”

[79] Bausch, “What moves me.”

[80] Sanasardo, phone interview.

[81] John O’Mahony, “Dancing in the Dark,” The Guardian, U.S. Edition, January 25, 2002.

[82] Bausch, “What moves me.”

[83] Bausch, “What moves me.”

[84] See Pina Bausch online archive at https://www.pinabausch.org/piece/phi.

[85] Quoted in Jack Anderson, The American Dance Festival (Durham: Duke University Press, 1987), 143.

[86] Gloria McLean, email to author, October 28, 2022.

[87] Judy Kahn, “The Paul Sanasardo Dance Company,” Dance Magazine, October 1972, 86.

[88] Marcelo de Andrade Pereira, “On Pina Bausch’s Legacy: An Interview with Dominique Mercy,” Brazilian Journal on Presence Studies, Originally in Rev. Bras. Estud. Presença, Porto Alegre, v. 8, n. 3, p. 539-554, July/Sept. 2018. Available here.

[89] Daly, “Remembered Gesture,” 29.

[90] Quoted in Pereira, “On Pina Bausch’s Legacy.”

[91] Judith Canner Moss, email message to author, February 15, 2022.

[92] Bausch, “What moves me.”

[93] Video recording of Dance Magazine Awards, December 8, 2008, Florence Gould Hall, unpublished.

Historical Essays 8