When Trey McIntyre Project was going strong, the synergy between Trey as choreographer and John-Michael Schert as dancer-cum-executive-director was the juice that stoked this company’s success. Whatever creative projects McIntyre came up with, Schert figured out how to implement them in a way that strengthened their role in a community—both local and international. Trey was the dreamy, dreaming one and John-Michael was the practical one. Together they created a juggernaut that turned Boise into a city of dance lovers.

Three years ago, when Dance Magazine did a cover story on the company , it seemed the TMP would last forever. The company had found an ideal home in Boise and was continuing its dense schedule of touring. Audiences all over the world responded to their snappy, fun, witty, complex choreography. As I wrote in 2009, McIntyre really knows how to use music that brings big pleasure to a broad audience.

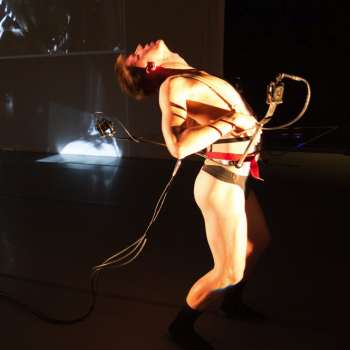

Chanel daSilva and John-Michael Schert, photo by Lois Greenfield

Trey McIntyre

So when it was announced in January that this week’s run at Jacob’s Pillow will be its last, many speculated on the cause of TMPs demise. Marina Harss quotes McIntyre in her story in yesterday’s New York Times as saying he doesn’t want to undergo the “creative sacrifice” any more. Fair enough. Running a dance company can be a burden, especially when a choreographer is still getting lots of freelance work or wants to pick up a camera instead of walk into a dance studio.

But I am also guessing that the chemistry, once Schert left, just wasn’t there any more. And that must have changed the balance of responsibilities drastically.

By the way, I don’t think the loss of TMP is a tragedy, at least for dance lovers outside of Boise. Yes, he is one of the best American choreographers, and in the old social order, he should have his own company. But things are changing. We can see McIntyre’s work in many other companies—Cincinnati Ballet’s wildly fun rendition of his madcap Chasing Squirrel at the Joyce was a recent example. And Schert has gone on to become visiting artist, mentor, and social entrepreneur for the University of Chicago Booth School of Business and UChicago Arts.

Just remember, even the Beatles only stayed together a few years.

Featured Uncategorized Leave a comment

With the drumbeat accelerating, the uneven earth commanding one’s attention so as not to fall, and the exhilaration of being among other runners (and walkers), it was easy to forget the purpose of the run. But at the end Anna brought us back to our purpose. She asked us to sit back-to-back with a neighbor for a few minutes, then face that person and tell her or him of our plans to bring our stated goal closer to reality.

With the drumbeat accelerating, the uneven earth commanding one’s attention so as not to fall, and the exhilaration of being among other runners (and walkers), it was easy to forget the purpose of the run. But at the end Anna brought us back to our purpose. She asked us to sit back-to-back with a neighbor for a few minutes, then face that person and tell her or him of our plans to bring our stated goal closer to reality.