Now that Trisha Brown is no longer making new work, every opportunity to see her past pieces is to be cherished. For the company’s engagement at New York Live Arts, they have reconstructed Son of Gone Fishin’ (1981) with new costumes by the original costume designer, Judith Shea. This work is so complex that it’s hard to glean any sort of structure on first viewing. My advice is to just follow the dancing—and the hypnotic music by the late Robert Ashley.

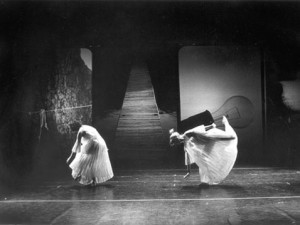

The program also includes one of Trisha’s most beautiful and haunting works: Opal Loop/Cloud Installation #72503 (1980). The cloud of vapor (it’s not dry ice but a water sculpture by artist Fugiko Nakaya), underscores the dissolution of all things; you never know what part of the dance you will see. The costumes are the best because each of the four dancers looks like they are from a different movie.

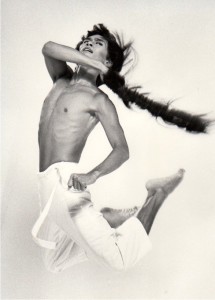

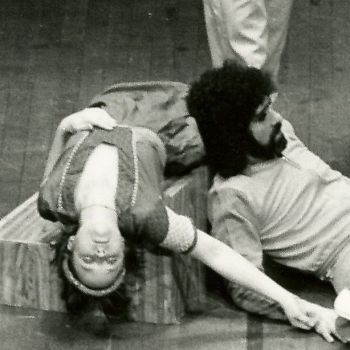

The company is also bringing back Solo Olos, which I danced as part of Line Up in the 70s. We learned it forward, backward, and with “Spill” —a nicely messy little detour. We were able to reverse the phrase on a dime, or rather on the impromptu instructions of the “caller.” It keeps your brain on its toes, as it were.

April 8–13, 2014, with various workshops offered. Click here for tickets.

In NYC Uncategorized what to see Leave a comment