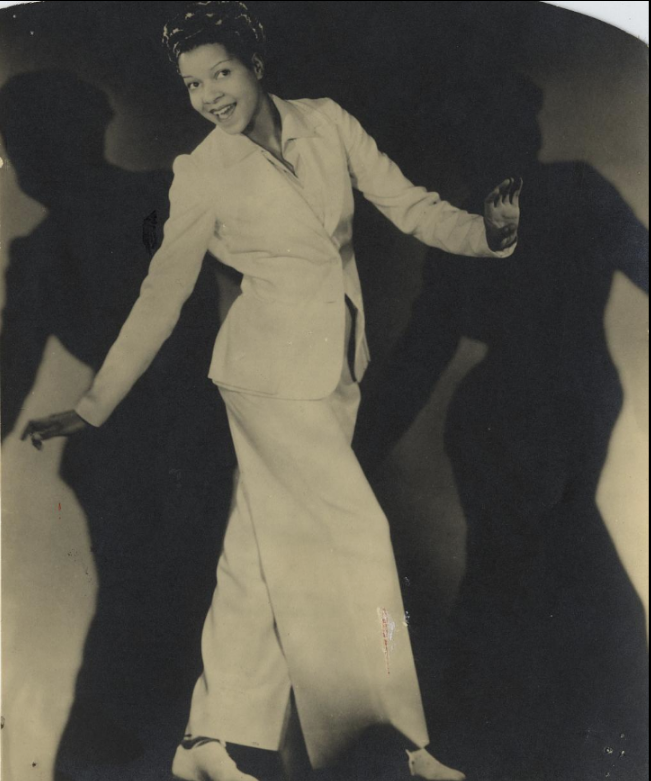

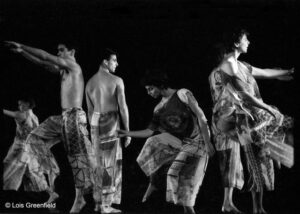

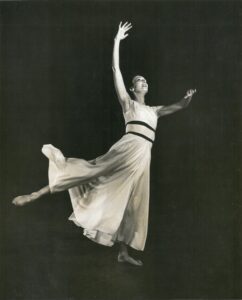

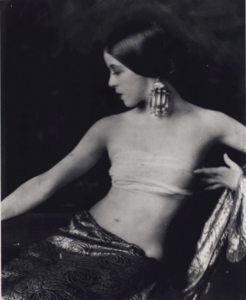

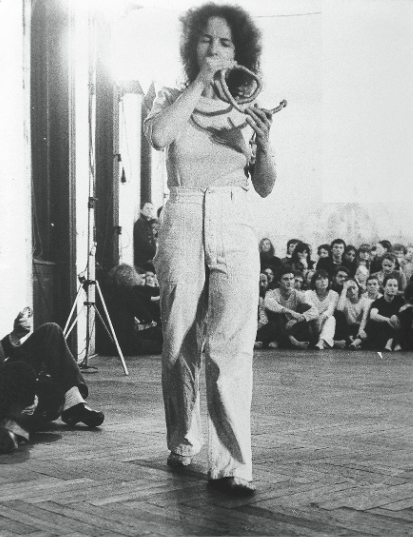

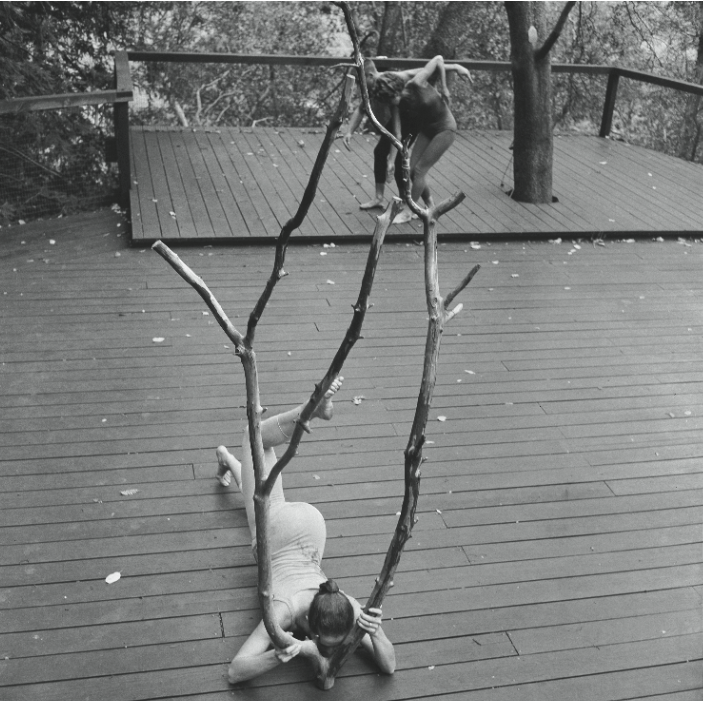

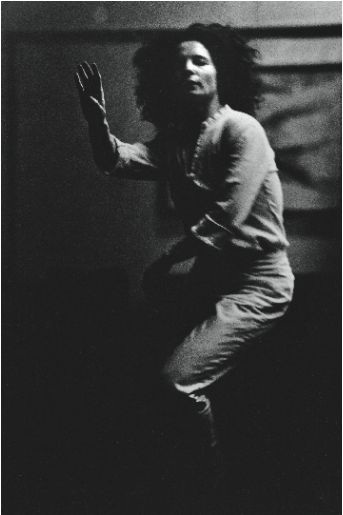

With swinging arms and flashy legwork, Jeni LeGon could tap her way onto any stage or screen. Her lively eyes and enchanting smile put audiences in a good mood. Less polished than her white counterparts like Ann Miller and Eleanor Powell, she was more inviting, more joyful. There was a freedom to the way her limbs expanded a bit too much, her energy spilling over. When she rose up in a toe stand, it was as though sheer effervescence pulled her up.

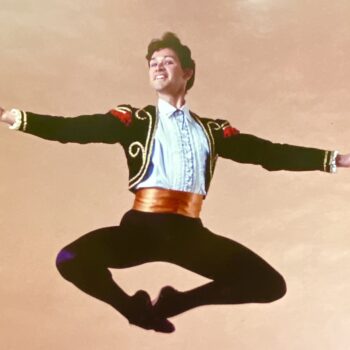

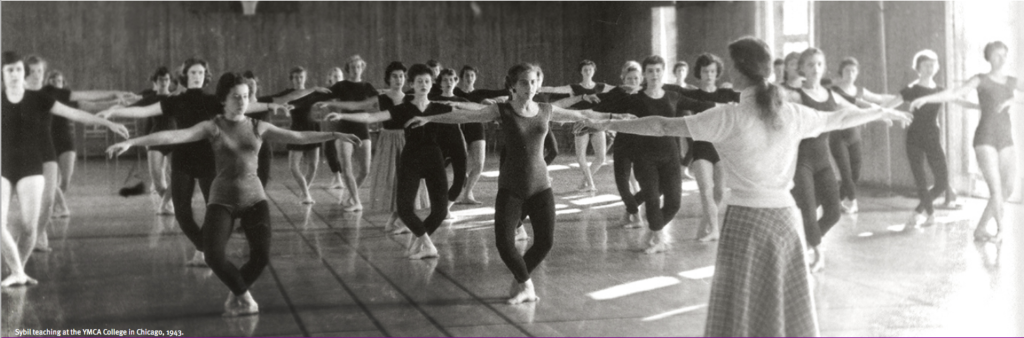

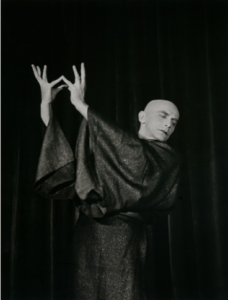

Publicity shot, Smithsonian Papers

The first Black woman to sign a long-term contract with a major Hollywood studio, LeGon was caught between Hollywood’s ambivalent attempt at inclusion and the racism that was everywhere. If MGM had followed through on that contract, there would be a cluster of good movie musicals starring Jeni LeGon. But the opportunities she had to shine were mostly limited to low-budget Black musicals. Luckily, we can treasure glimpses of them on YouTube.

Jeni LeGon (née Jennie Ligon) grew up in a large, musical family on Chicago’s South Side. As a child, she took a few dance lessons at the Mary Bruce’s School of Dancing, but mostly she learned to tap in neighborhood theaters. In those days there was a stage show and a movie, and both would repeat. Duke Ellington and Cab Calloway would tour to one of the Chicago theaters with their bands and their dancers. Twice a week Jeni would use her lunch money to spend a day there. She’d watch the stage show, then, when the movie played, she’d go upstairs to the lobby to try out the steps. For the last stage show of the day, “I’d go back down and watch ’em again to see if I had remembered the steps well enough to get ’em in my head.” (qtd. in Greschuk) She would dash home to make it by 6:00. She never told her mother until years later that she had skipped school. In a sense, those stage shows were her schooling.

On weekends she organized “show gangs” with what she called “tramp bands” that might include a kazoo, a bass made of a string attached to a washtub, singers, dancers, and drummers (even if it was just tin pans or cardboard boxes). They performed to “patrons” who sat on the stoops:

We charged a nickel and a dime, people would sit on the steps and we would be on the sidewalks. We had kids who could do acrobatics or could sing. I was the boss. I’m a Leo, I was the head honcho. (qtd. in Abbott)

Her brother was an exhibition ballroom dancer and together they would enter competitions and sweep up. When she was only 13 or 14, she auditioned for the chorus line of Count Basie’s new band. She was the youngest and least developed, so when the new chorus girls tried on the sexy two-piece outfits, she didn’t fill it out.

“The bra hung down… and I felt so silly,” she recalled decades later. “The director had a fit: “What am I going to do with you?” I said, “I don’t wear those things. I always wear pants.’ ” When he found out she could sing, he said, “Then you don’t have to dance with the line, you can dance out front.” (qtd. in Greschuk) She had to quickly back up her claim by assembling a snazzy suit outfit with contributions from family members.

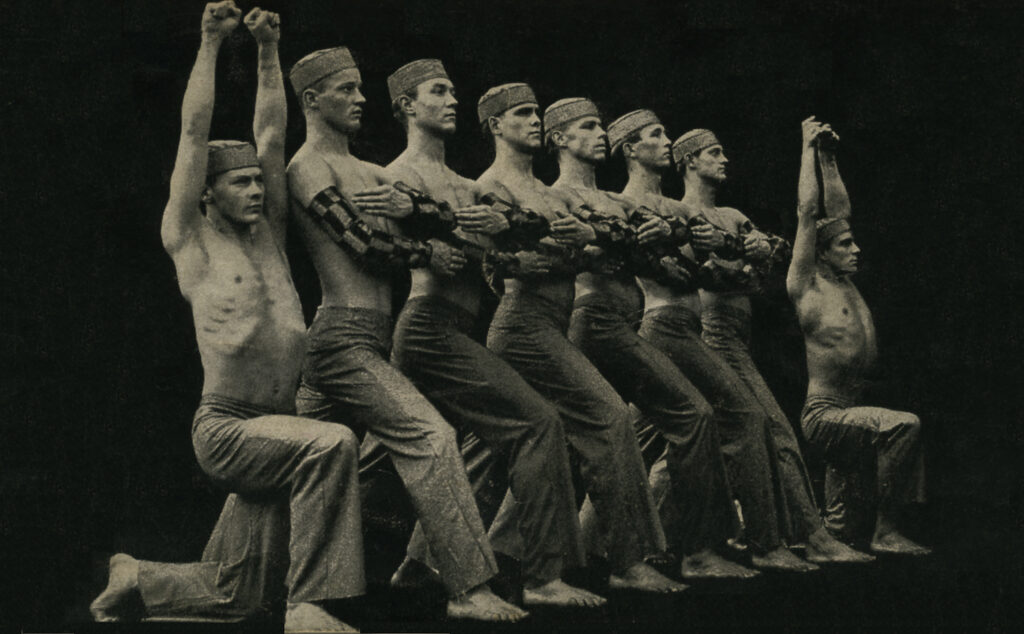

At 15, she joined the Whitman Sisters. Considered the royalty of Black vaudeville, the four Whitman Sisters were the only touring group produced and managed by Black women. The four sisters were known for cultivating the talents of many Black entertainers, including Count Basie and tap dancer Leonard Reed. They toured their variety show with a jazz band, comedians, acrobats, and a chorus line. As LeGon recalled,

The Whitman sisters had fixed the line so we had all the colors that our race is known for. All the pretty shading — from the darkest, darkest to the palest of pale. Each one of us was a distinct-looking kid. It was a rainbow of beautiful girls.” (qtd. in Frank, 122)

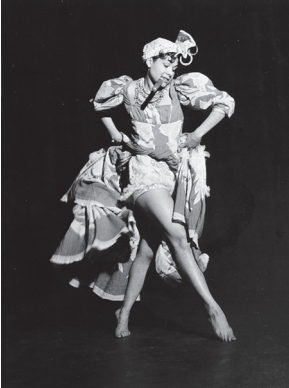

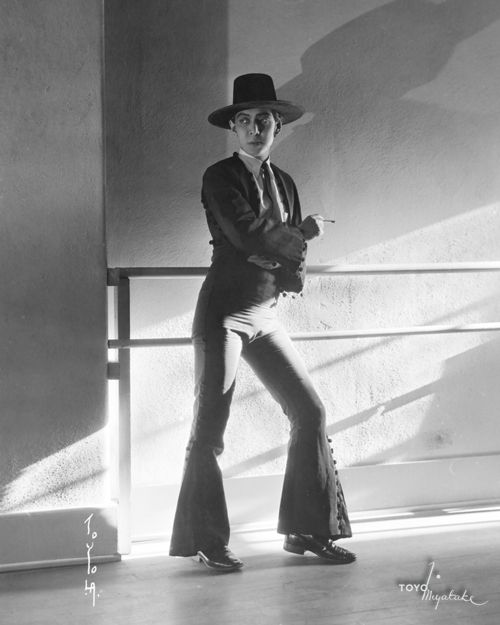

They toured the South, which was a daunting prospect for Black groups. For the first time in her life, LeGon saw signs requiring segregation in public spaces. But the Whitman group, numbering twenty or thirty performers, was well prepared: Mabel, the eldest sister and the one in charge of bookings, had arranged for hotels and rooming houses that served Blacks in every city. Alice, the youngest, was known as the top female tapper of the day, and Jeni would watch her hungrily from the wings. (Abbott) Alberta, calling herself Bert, would perform in pants, which must’ve confirmed for Jeni that it wasn’t too crazy a thing to do¹. Stepping out of the chorus line, LeGon was part of the Three Snakehips Queens (Malone 62), who performed a version of the dance popularized by Earl “Snakehips” Tucker: swiveling the pelvis, undulating the spine, and shimmying feverishly.

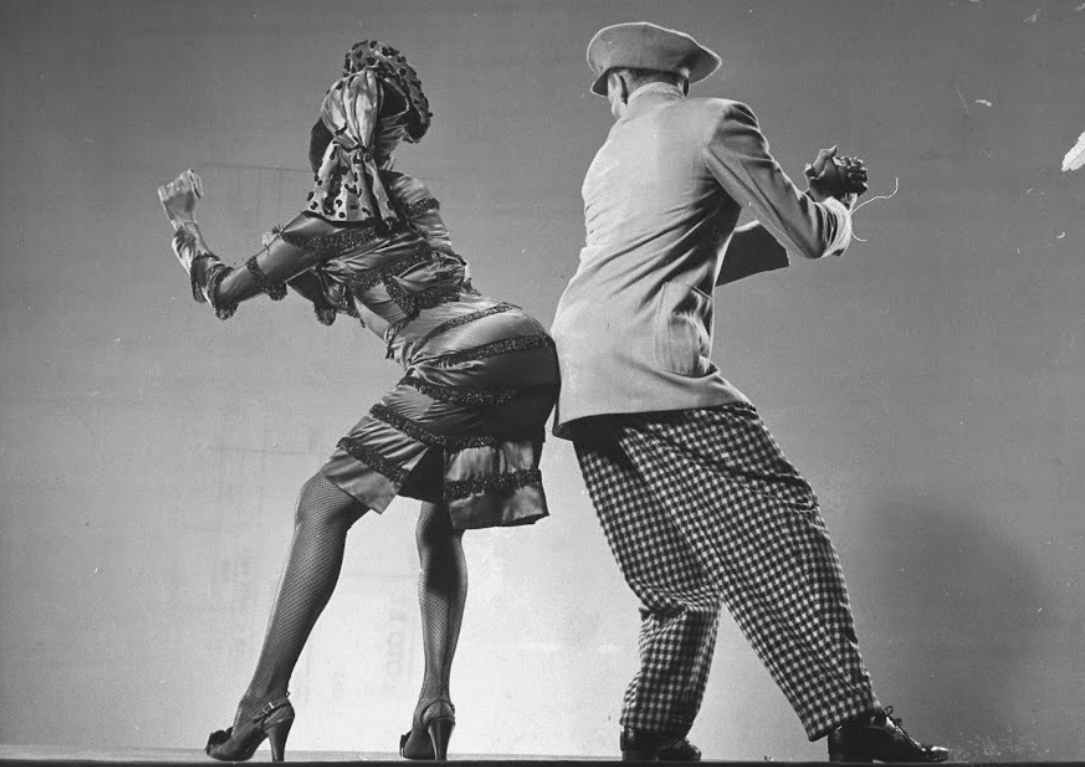

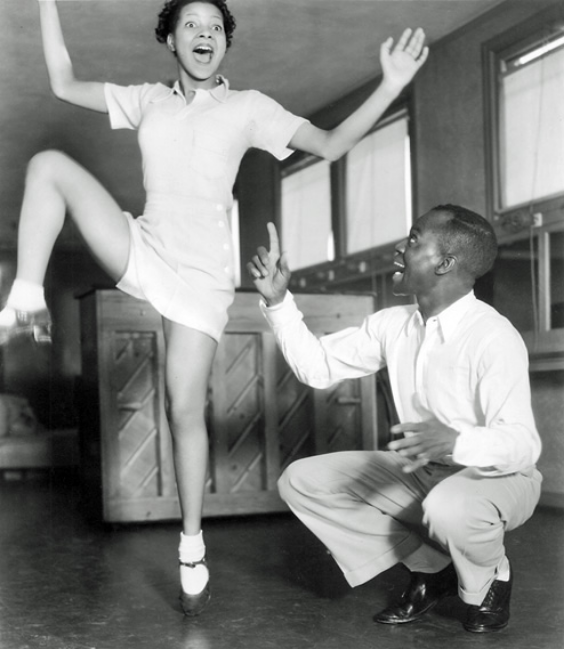

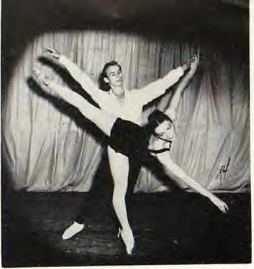

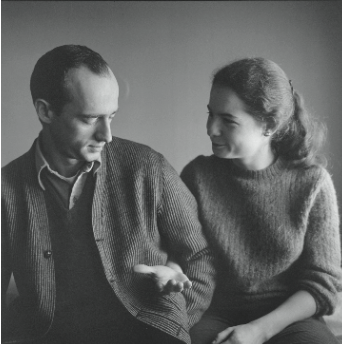

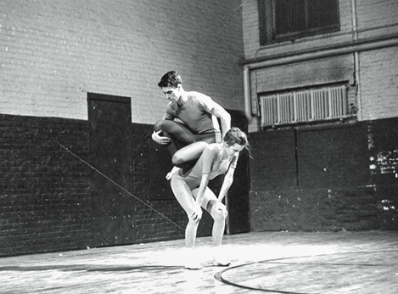

Robison and LeGon, RKA-Radio Detroit publicity ph Robert W. Coburn

After a season with the Whitman Sisters, LeGon formed a duo with her foster sister, Willa Mae Lane, for which she wore the pants and Willa Mae wore a skirt. They were performing in Detroit with other talented youth when they were approached by a man who claimed he would get them work at the Culver City Cotton Club. So sixteen of them took a bus out to Hollywood … but the gig never materialized.

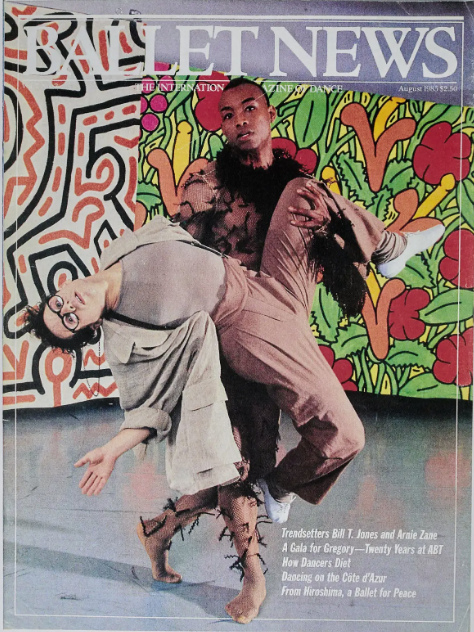

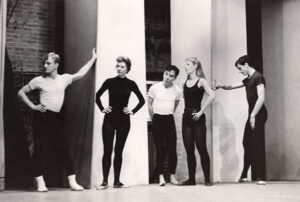

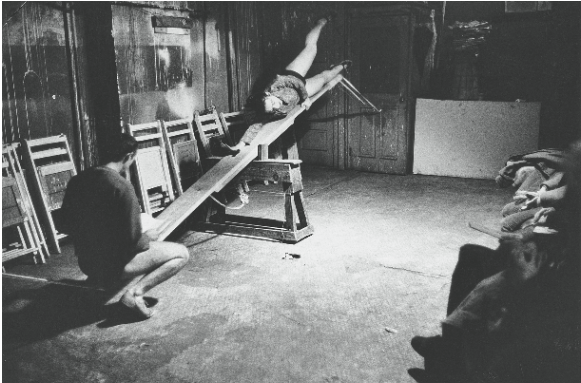

Somehow they got connected to Earl Dancer, who had been Ethel Waters’ manager. According to LeGon, Dancer “used to supply Black talent for all the studios.” (Crowe) He organized a performance for casting directors at the Wilshire Ebell Theater. In the audience was RKO, which had just signed Bill Robinson and Fats Waller to appear in Hooray for Love. They liked LeGon so much that they added her to the cast. (This was 1935, the year that RKO released two films with Robinson and Shirley Temple dancing together.) LeGon was the first Black woman to dance with Robinson on screen.

On the RKO lot all the dancers rehearsed in the same building—and that included Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers. LeGon and Robinson had a congenial relationship with the famous pair. According to LeGon, “We’d stop by one another’s rehearsal and do a little bit of exchanging of steps and yakkity yakkin’ and stuff like that. It was fantastic.” (qtd. in Frank 123) But she was never invited to any of the white performers’ homes except for Al Jolson and Ruby Keeler, and that was probably because Jolson and Earl Dancer were good friends.

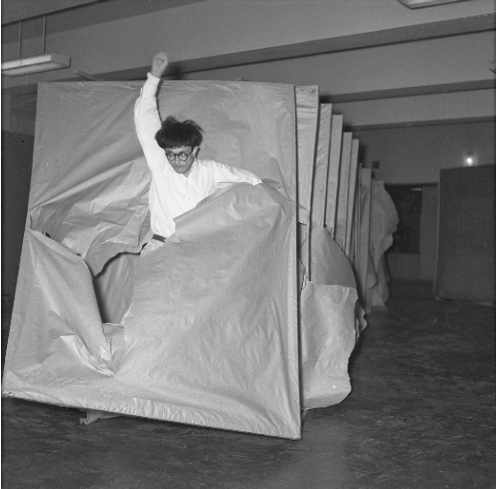

Robinson & LeGon

In Hooray for Love, her song-and-dance number with Robinson, “Living in a Great Big Way” is part of a set play within a play. Jeni’s character is a forlorn young woman who’s just been evicted from her home. Wearing a white turtleneck and dark trousers, she looks like a gamin, a tomboy. Robinson struts on, twirling his cane; he is the flamboyant “mayor.” (Robinson’s real-life nickname was “Mayor of Harlem” so he was basically playing himself.) He snaps his fingers to snap her out of the doldrums. She gamely clicks and taps along, with what Constance Valis Hill calls “her added bounce and genuine sweetness.” (Hill 124) Her casual, un-Hollywood look only adds to her charm. Her movement quality—loose torso, flowing arms, head bobbing—contrasts with Robinson’s centeredness. Fats Waller, as one of the moving men, starts jiving along with them, then impulsively plays the piano that’s been put out on the street. With the help of Robinson’s upbeat rhythm and Waller’s jazzy piano, her character transforms from melancholy to cheerful.

LeGon loved dancing with Robinson, who was the supreme tap legend, then and now. “I was floored. Just to think that me, a little skinny-legged kid coming out of Chicago…to be able to work with him was the highlight of my life.” She appreciated his rigorous approach. “Bill was a task master. When he was showing something you paid attention and you got it. He wouldn’t do it twenty times. He’d do the step two or three times and you’d better get it.” (qtd. in Greschuk) An added bonus: He taught her to like ice cream. (Crowe)

The audience response to her at the opening preview was ecstatic:

After Hooray for Love was shown, we went out in the lobby, and the people just descended on me like it was no tomorrow! — asking for my autograph and congratulating me, and all that sort of business. As I’ve said before, at that time, we lived in this black-and-white world, definitely. But here were all these people of the opposite race hugging and kissing me, and man, I thought they had lost their minds!…It was just glorious that all those people would stop me and talk to me that way. (Frank 124)

Did she think they had “lost their minds” because they weren’t behaving the way white people normally behave toward Black people? Scholar Nadine George-Graves interprets those three words as meaning “The minds they lost were their rationalizations for their typical treatment of African Americans.” (George-Graves 535) For that moment of appreciation, they suspended their usual sense of superiority.

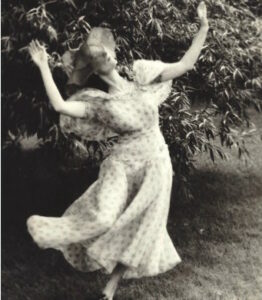

Mid-1930s

Jeni was so successful in Hooray for Love that Earl Dancer was able to convince the head of MGM to put her under contract. MGM immediately cast the young tapper in a supporting role in the upcoming movie Broadway Melody of 1936, starring Eleanor Powell. At a dinner to promote the show (some called it a charity banquet), LeGon was to perform a number from the film as an opening act for Powell. But her dancing was so beguiling that she received two encores. (Spaner) “They kept applauding and I’m bowing, bowing, bowing.” (qtd. in Crowe) It was just a little too much love shown for the opening act and not enough for Powell. The next day, Arthur Freed from MGM told Jeni’s manager, Earl Dancer, that they could not have two female soloists, so they dropped LeGon. This was rather abrupt considering MGM had circulated this announcement: “JENI LEGON: MILLION DOLLAR PERSONALITY GIRL SIGNED.” (displayed in Greschuk) She was to receive a hefty weekly salary of $1,250 that could be raised each year for five years to a maximum of $4,500. MGM must’ve seen a gold mine in her—at first.

She never did play a lead in an MGM movie.

Triumph in London

After negotiating with Earl Dancer, MGM arranged for the young tapper to star in the London cast of C. B. Cochran’s At Home Abroad, a revue whose New York cast had been led by Ethel Waters and Eleanor Powell. On the way to London the title changed to Follow the Sun; LeGon sang Waters’ songs and danced Powell’s routines. She was a hit. A reviewer for Empire News raved:

Jeni LeGon is one of the brightest spirits that ever stepped on the stage. It seems that little Jeni LeGon is overshadowing all other entertainers…Jeni LeGon, the sepia Cinderella girl who set London agog with her clever dancing and cute antics. (qtd. in Frank 126)

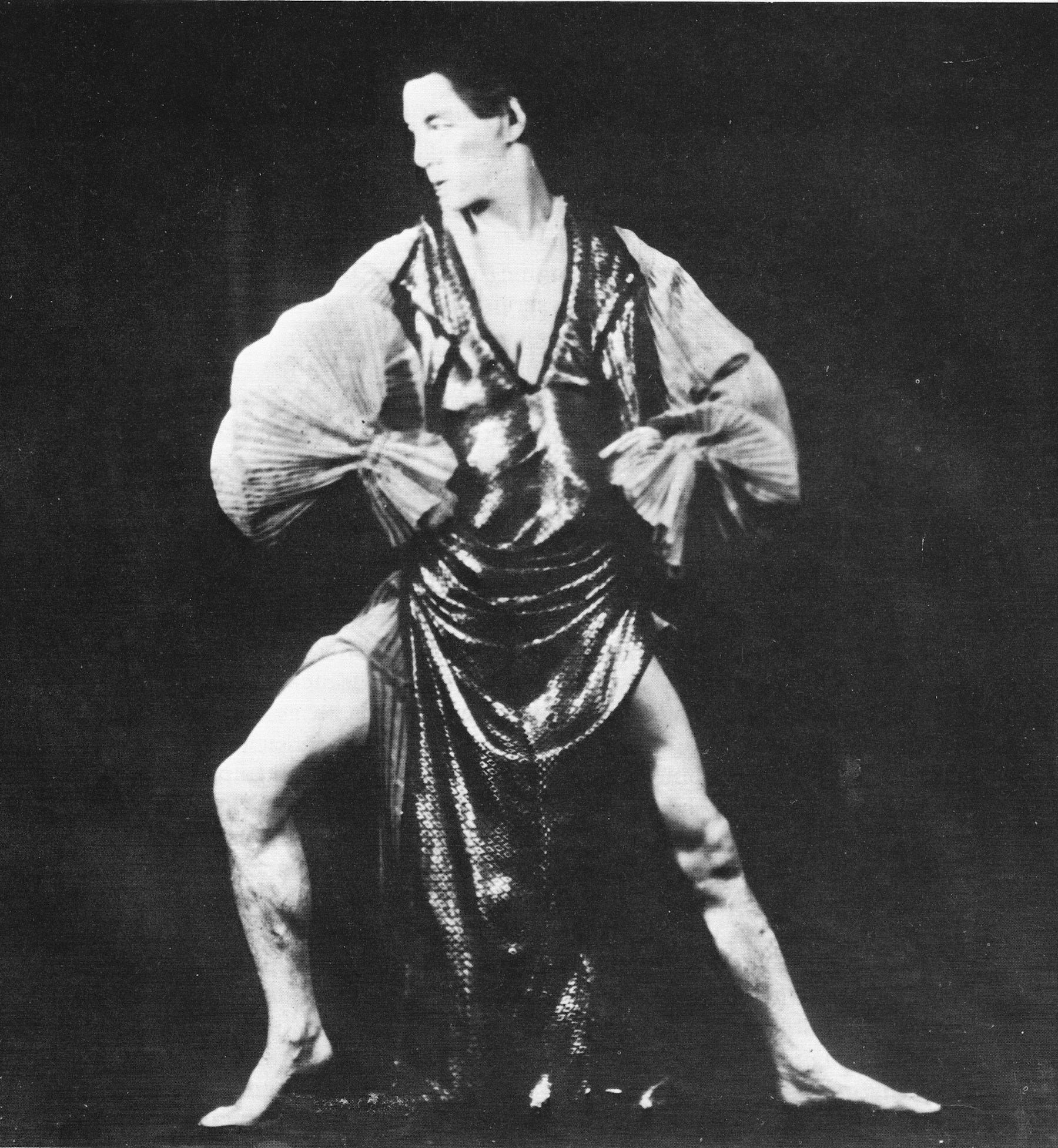

Dishonour Bright 1936

She loved London and its lack of American racism:

It was an entirely different kind of life. We went from black and white to just people. It was the first time I had been addressed by Miss LeGon. I didn’t have to worry about going to places and being told I couldn’t come in. (qtd. in Greschuk)

During her two-year stay in London she was very social. Guests at her birthday party included the Nicholas Brothers and singer/actor/activist Paul Robeson, who was friends with Josephine Baker. Though LeGon had never seen Baker dance, she emulated her from what she knew about her—being the end girl in the chorus line, taking comedic risks. (Her scene in Ali Baba Goes to Town with its over-the-top faux savagery, could have come right out of a Baker number. More about that later.) Through Paul Robeson and Earl Dancer, LeGon was introduced to Baker. “I finally met her—over the phone. Oh, I just carried on like a fool!” (qtd in Frank 125)

While in London she made the film Dishonor Bright (1936), a romantic comedy in which she played a cabaret dancer. She wanted to stay in London, where she was treated so well, but returned to the States in 1937 because of the first stirrings of war.

The Hoofers’ Club

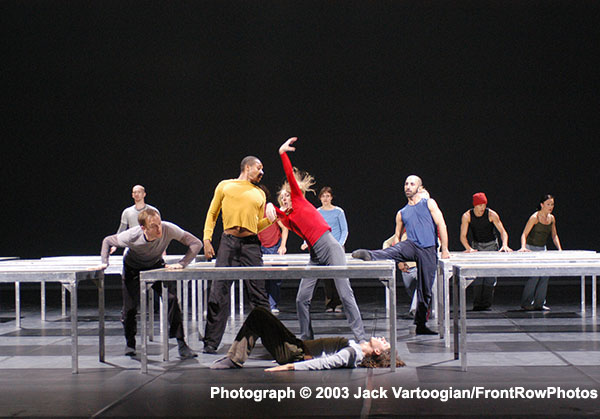

Publicity shot for Hooray for Love

Almost as soon as she landed in New York, she was recruited to the Hoofers’ Club in Harlem, “the epicenter of twentieth-century tap” according to tap aficionado Brian Seibert. (Seibert 21) This was a small room with a piano in the same building as gambling and a pool hall. LeGon recalls that it was probably John Bubbles who brought her, and she was one of the very few women invited—possibly the only one. Bubbles, Robinson, Eddie Rector and other top tappers were regulars. It was a place for jamming, but it was rigorous: If the others didn’t like what you did, you would not be invited back. Or you would go away and work on your steps until you could master them, and along the way you developed your own style. The credo, according to Hill, was “Survive or die.” (Hill 87). LeGon valued both craftsmanship and “selling” it. “I absorbed it. Every time I’d see something that I liked, I would take it and tear it to pieces and make it my own.” (Qtd in Frank 127) The Hoofers Club, which lasted into the 40s, was portrayed in the movie The Cotton Club as a smoke-filled room where the denizens casually showed off their virtuosity.

More Screen and Stage

LeGon returned to Hollywood to make more films. In the all-black cast of Double Deal (1939), she is Nita, a cabaret dancer who is desired by both the gangster and the honest guy, played by popular Black actor Monte Hawley. Dancing her own choreography in “Getting it Right With You,” she does some Charleston-derived tapping, a bit of truckin’ and a hint of a rumba. Her flyaway arms and softly kicking legs signal a glorious comfort with her own body. When she throws her head back in joy you’re convinced she’s having the time of her life. (No wonder she brought the house down as a warmup act for the more severe Eleanor Powell!) This was a cherished role. Not only was she the romantic lead, but she got to dance her own steps — “Being myself when I danced as me.” (qtd. in Greschuk)

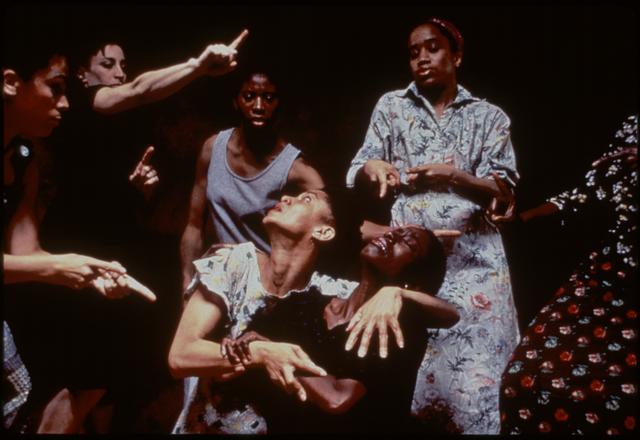

Dying in Cab Calloway’s arms in Hi De Ho

Double Deal was the first of four all-Black movies where she played a heroine. The next one was Crooked Money, later called While Thousands Cheer (1940). She plays Myra, who helps her boyfriend, the star of the college football team, outwit the gangsters. In Take My Life (1942), she was paired with Hawley again, as his character’s wife. This film also featured Harlem’s Dead End Kids, a group of talented boys who appeared on Broadway as well as in Hollywood. The last of these was Hi De Ho (1947), a vehicle for Cab Calloway. Here she is cast against type as the possessive, threatening girlfriend. The script is so bad that one cannot even judge her acting in it: “I’ll see you dead before I let anyone take you from me,” she says to the man she loves. He slaps her, of course. But, as she said years later, “I got to die in Cab Calloway’s arms.”

Fats Waller

From her days working on Hooray for Love, LeGon made fast friends with Fats Waller, who hired her for four of his shows including one at the Apollo (Crowe). He coached her on how to present a song, and you can see his influence in the way she rolls her eyes with a sense of mischief. She describes a particular skit where they one-upped each other: He would play a jazzy lick on the piano and challenge her to do it with her feet; then she’d tap a complicated rhythm for him to replicate on the piano. All the while Waller would be wise-cracking with his usual campy one liners like “All that meat and no potatoes.” They goofed off elaborately during their exit, with each miming No you go first. “And finally I would exit and he would grab the curtain and shake his bum! We would tear up the place!” (qtd. in Frank 125)

The last show she did with Waller’s music was Early to Bed, which opened at the Broadhurst Theatre in 1943. She landed the featured role of Lily Ann. Also featured was George Zoritch, a star of the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo. In a 2004 interview, LeGon recalled that Katherine Dunham’s company was performing nearby and she would go to see their Sunday matinee when Early to Bed was off. (Crowe) My guess is that she brought Zoritch with her, because he writes in his memoir that he started studying with Dunham around that time. (Zoritch 117) (I probably don’t have to tell you how rare it was for a Russian ballet dancer to study Dunham technique!)

Easter Parade (1948) with Ann Miller and Fred Astaire

One of her more active of her many servile roles was in MGM’s Easter Parade (1948) with Fred Astaire and Judy Garland. She plays Essie, the loyal maid to Ann Miller’s Nadine, the glam ballroom dancer. (I wonder if any of the executives at MGM remembered the high salary they first offered their “personality girl” thirteen years before.) Jeni manages to wedge in a bit of humor in addressing two of Nadine’s pets. To the first puppy she says, “C’mon, Short Hemline.” To the second one, a little pug, she says, “Who pushed your face in?” The 2010 Turner edition of the Easter Parade DVD carries a special feature in which John Fricke, a Hollywood historian, gives LeGon a morsel of attention. He calls her “this amazing talented dancer,” ticks her credentials like working with Count Basie, Fats Waller, and Bill Robinson, and claims she could equal the Nicholas Brothers “with acrobatics and the tap and all the style.” No mention of why, with all that talent, she was cast as the maid.

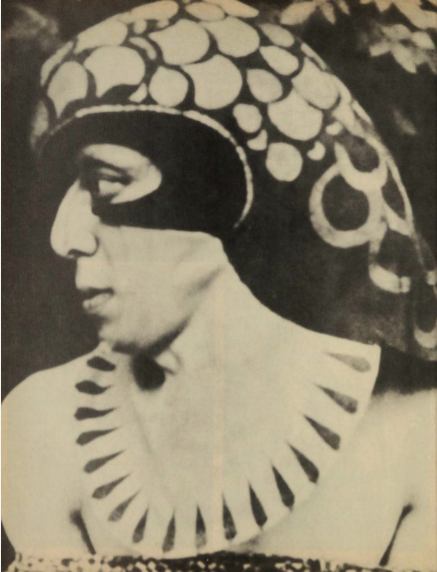

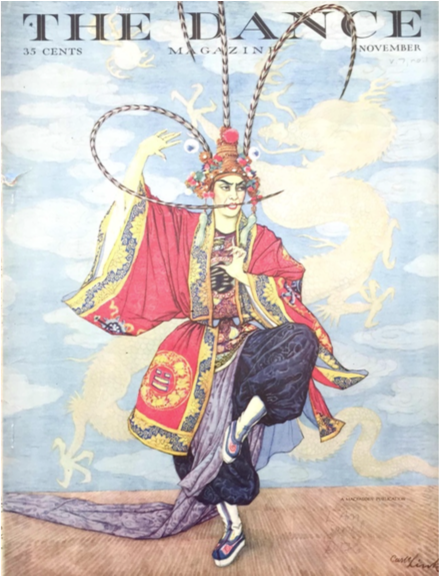

Magazine cover, 1937

LeGon occasionally branched out into writing. With her husband at the time, the jazz composer and lyricist Phil Moore, she wrote the song “The Sping,” blending Spanish and swing; they offered it to MGM for Lena Horne in Panama Hattie (1942). MGM accepted the song and asked LeGon to come and stage it. LeGon and Moore also wrote The Matriarch for Ethel Waters, though it was probably never produced. (A bit of gratuitous gossip: Moore, whom LeGon met while working on Double Deal, went on to become a composer, booking agent, and lover of Dorothy Dandridge.)

Activism: LeGon’s and others’

Around 1950 LeGon joined a group of performers seeking to raise the opportunities for Black actors to have dignified roles. They called on Ronald Reagan, then president of the Screen Actors Guild, to support their cause. About his response, LeGon said, “We tried to get him to intervene for us, but he wasn’t the least bit sympathetic. He didn’t even lie about it.” (Ebert) [2] She was friends with Paul Robeson, whose 1956 encounter with the communist-hunting House UnAmerican Committee destroyed his flourishing international career. It’s not surprising that many Blacks pulled back from protesting during that period.

While she lobbied for better roles for Blacks, LeGon also wanted to hold on the roles that were available. In the early 1950s, she appeared on the televised version of Amos ’n Andy, often as Kingfish’s secretary. She was sorry to see it cancelled:

It was one of the best all-around casts that I ever worked with. All the leads were exceptionally good performers. Amos and Andy and Kingfish and his wife Sapphire—a wonderful experience. A couple of the characters didn’t speak too well…deeze, dat and doze. The Black community got mad and wanted to cancel it. They succeeded and threw a whole bunch of people out of work. But the show was true to life, that was what was so funny about them—things that happened to everybody. I loved them, I thought they were grand.” (Greschuk)

The attacks on the show had actually started decades earlier.[3]

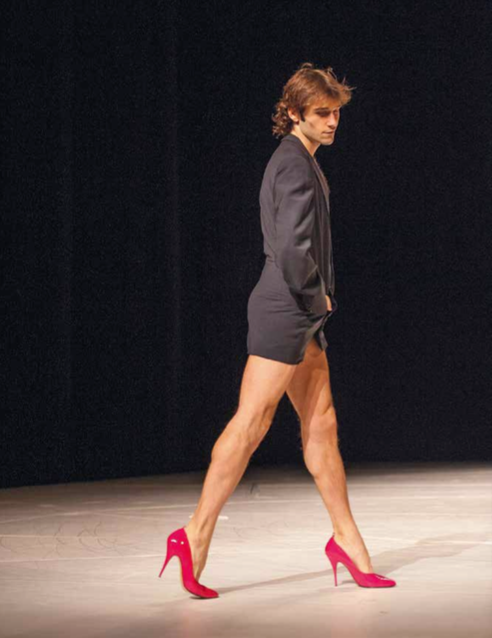

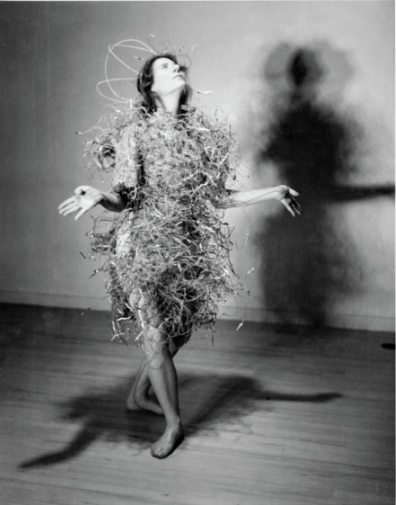

Boyish? Girlish? Mannish?

Although LeGon liked wearing pants while she danced, a headline in Sight & Sound that proclaimed she danced “like a boy” is misleading (Hutchinson). Yes, she did the boys’ moves like flips, knee drops and a man’s split (as in the Nicholas Brothers). But she did not take on male characteristics. She wasn’t like the flamenco dancer Carmen Amaya, who wore trousers to emphasize her jabbing male heel-work, transcending femininity with a volcanic force. She wasn’t like Marlene Dietrich, who wore pants to add a note of androgyny to her sexual allure. (Dietrich once said to her, “I say, my dahlink, you wear the pants better than I do.” (qtd. in George-Graves 517) I think she wore pants to edge away from the expectation of sultriness. Many glamorous female stars, like Lena Horne and Rita Hayworth, appear to be poured into their gowns. LeGon avoided that look even when she did wear a skirt or dress, and I think it kept her dancing fresh and energetic. Of course LeGon’s idol, Josephine Baker, made a fabulous mockery of seductiveness with her banana skirts and pelvic gyrations.

While singing “There’s a Boy in Harlem” in Fools for Scandal (1938), LeGon sways suavely in white top hat and tux. She could be that boy in Harlem herself. She’s backed by chorus girls wearing skimpy outfits or glitzy gowns, almost like a man would be backed by super femmy women. Her dancing here is minimal, sedate, allowing the fancy gowns to fill in the glamour quotient.

“There’s a Boy in Harlem” in Fools for Scandal

Later Years

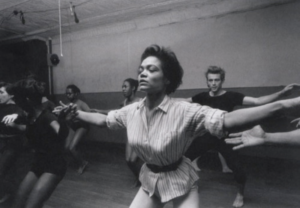

Starting in the 1950s, LeGon ran the Jeni LeGon Dance Studio in Los Angeles. She hired Archie Savage to teach Dunham technique and a Russian ballet dancer (Lazar Galpern — does anyone know this name?) to teach ballet. She taught jazz and tap herself. She organized a group with a steel band called Jazz Caribe that blended jazz and Calypso, in which she danced and played percussion. (She had learned to play conga drums from Dunham drummer Gaucho Vanderhans.) For five years they played gigs at clubs as well as military posts.

She sometimes took on choreographic assignments outside her circle. In 1965 she worked on the West Coast premiere of William Grant Still’s “African” ballet Sahdji (1930) with a full symphony orchestra and the Combined Youth Choruses of the City of Los Angeles. (Dance Magazine, July 1965)

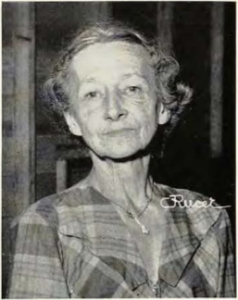

LeGon in 2009

After two former students set her up to teach in Vancouver, she moved to that city in 1969. Basing her school at Kits House (Kitsilano Neighbourhood House), she formed a youth tap group called Troupe One that performed in hospitals and senior homes. In the mid-80s, she also had a jazz group, Jazz Cinq, that played Ellington, Cole Porter, and the blues. She’d sing, dance, and play congo drums, timbals and “scratchy instruments” in the band. (Creighton)

In the 1980s she visited London with a group called the Pelican Players. She also re-united with the Nicholas Brothers for a radio show in Oakland (Crowe). She was in Cold Front with Martin Sheen in 1989 (Creighton) (though her scene may have been cut because she is not listed in IMDB.) One of her last appearances was in Snoop Dogg’s 2001 film, Bones.

Jeni LeGon had a fruitful career, but she should have had more opportunities to really dance. She made bold choices from the beginning. As Rusty Frank has written about early tap dance, “The rarest act of all was the girl solo.” (Frank 118) On screen LeGon was not only a dancer with a unique style, she was appealing as a romantic heroine: attractive, savvy, expressive. Just as RKO took a risk when they paired Shirley Temple with Bill Robinson, MGM could have taken a risk by fulfilling their contract with Jeni LeGon.

Coping with Racism

Hollywood studios have been racist since Birth of a Nation (1915). LeGon encountered discrimination almost immediately. When she signed with MGM, she was only 17, so she had to attend the school on the lot. Her classmates were four or five other teenagers, including Judy Garland and Mickey Rooney. She got along with the other kids, especially Mickey, but not with the teacher: “I was an ardent reader. She’d ask questions of our group…I’d raise my hand to answer. The teacher wouldn’t let me answer the questions.… She just looked [at me] like I wasn’t there.” (qtd. in Abbott) LeGon asked to be released from those classes and given private lessons. (For perspective: This is the period when Eleanor Roosevelt couldn’t even get President Roosevelt to consider an anti-lynching bill.)

Jeni could be defiant in her resistance, but she could also be playful. George-Graves relates a kind of game LeGon played with a friend when she returned to New York from London. She and the friend, who had also lived in London, would sit on a bus and carry on a conversation with their newly acquired British accents. They got a kick out of confusing the white people on the bus. They also would browse fancy Fifth Avenue stores like Bonwit Tellers and Tiffany’s, making comments like “I wonder, my dear, just how much this is in pounds.” (George-Graves 527)

In her essay “Identity Politics and Political Will: Jeni LeGon Living in a Great Big Way,” George-Graves speculates that a series of incidents could have turned MGM against her. The day before the event when she unwittingly upstaged Eleanor Powell, LeGon and Earl Dancer had tried to enter MGM’s main dining room to discuss the score, not realizing that segregation was still the rule. They were turned away. MGM’s hypocrisy did not elude her: “Here, they were paying me $1,250 a week and telling me I wasn’t good enough to eat in their dining room.” The dining room episode might have been perceived as defiance. That, plus her refusal to continue classes with the racist teacher, suggests George-Graves, could have made MGM executives skitter away from her. (George-Graves, 518-19) Perhaps, in finding her a gig in London, MGM was giving her a peach after taking away a plum—or taking away the whole orchard.

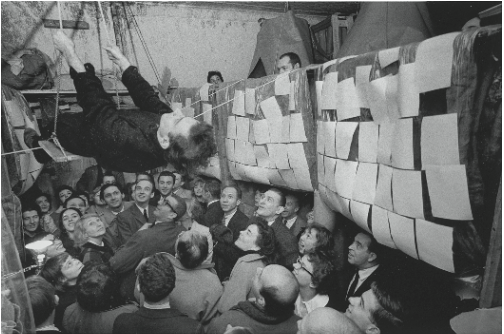

Duke Ellington at left, on his birthday party, 1937

When talking about racism, LeGon was careful not to lay blame. In one interview she described Judy Garland and Mickey Rooney as “the kids next door” and said, “I didn’t fit in at the time as one of the kids next door.” She recognized that “Hollywood was no different to the rest of the country in that respect.” (qtd. in Hutchinson) In hindsight, she said, “It was very difficult for any of the minority groups to break into the movies at that time.” (qtd. in Creighton) She did occasionally make a stronger statement: “At that time blacks and whites did not mix, even if you had a little intelligence and could carry on a conversation. But the world had been whitewashed.” (qtd. in Abbott)

LeGon was clear-eyed yet patient in the face of closed doors. Another performer might have quit after being relegated to servant roles so many times (at least nine of her twenty-four films). There was a practical aspect to her patience. As she told the Vancouver Sun in 1989,

I think I played every kind of black maid you can imagine. I’ve been a maid from the West Indies, Africa, Arabia. It was frustrating, but what was I going to do? You gotta eat, darling — you gotta eat. (qtd. in Bernstein)

Black women who followed LeGon also had a hard time in Hollywood. In the 1940s Lena Horne turned down roles of maids and prostitutes. Dorothy Dandridge, another dazzling dancer/singer/actress, also turned down demeaning roles. After establishing herself as a formidable leading lady opposite Harry Belafonte in Carmen Jones in 1954, Dandridge hit a dry spell of three years.

In Grant Greschuk’s documentary, Jeni LeGon: Living in a Great Big Way (1999), she says,

After thinking about it all the years…I don’t think it has changed an awful lot. There’s some changes that have been good…but basically I don’t think they’ve done too much. There’s still this black and white world.” (qtd. in George Graves 530)

She found a measure of peace in Vancouver. Although she was the only Black person in her residential building, her neighbors were welcoming and warm to her. And she was beloved by her students, which is obvious in the documentary. She met Frank Clavin, a drummer, in 1977, and they worked and lived together the rest of her life.

Awards and Honors

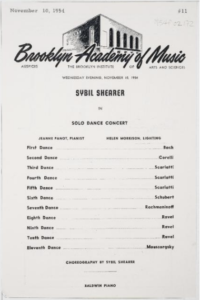

Publicity shot

In 1987 Jeni LeGon was inducted into the Black Filmmakers Hall of Fame —along with Sammy Davis, Jr. In 2000 she received the Flo-Bert Lifetime Achievement Award, and in 2002 she was inducted into the International Tap Dance Hall of Fame. That same year Oklahoma City University bestowed her with an honorary doctorate (along with eight others, including Fayard Nicholas, Leonard Reed, Jimmy Slyde, and Bunny Briggs). (Hill 330). And on her 90th birthday, British Columbia’s National Congress of Black Women Foundation held a luncheon in her honor. (Spaner)

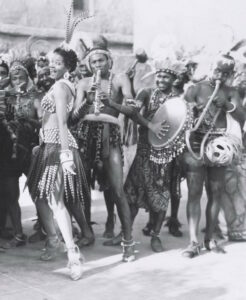

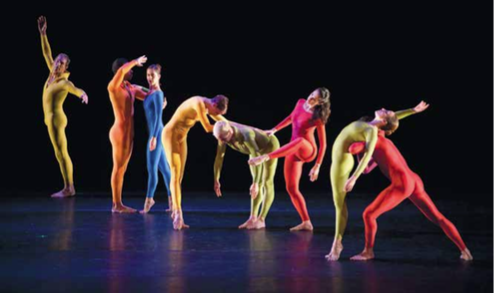

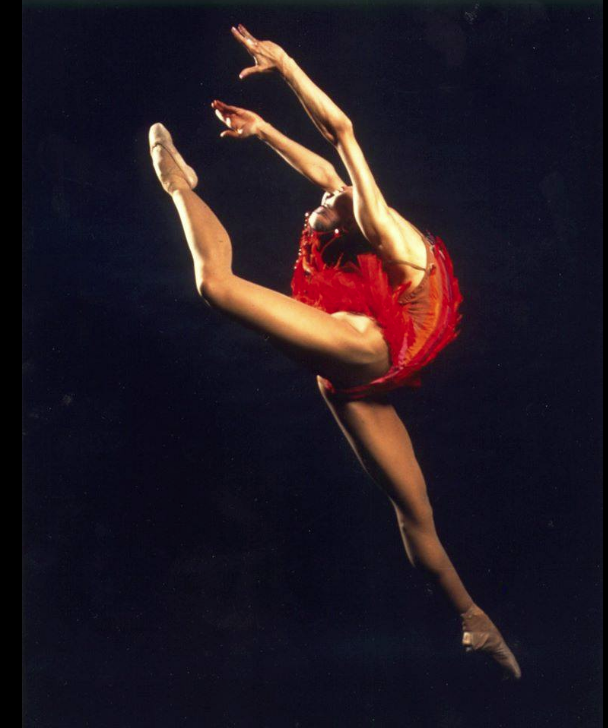

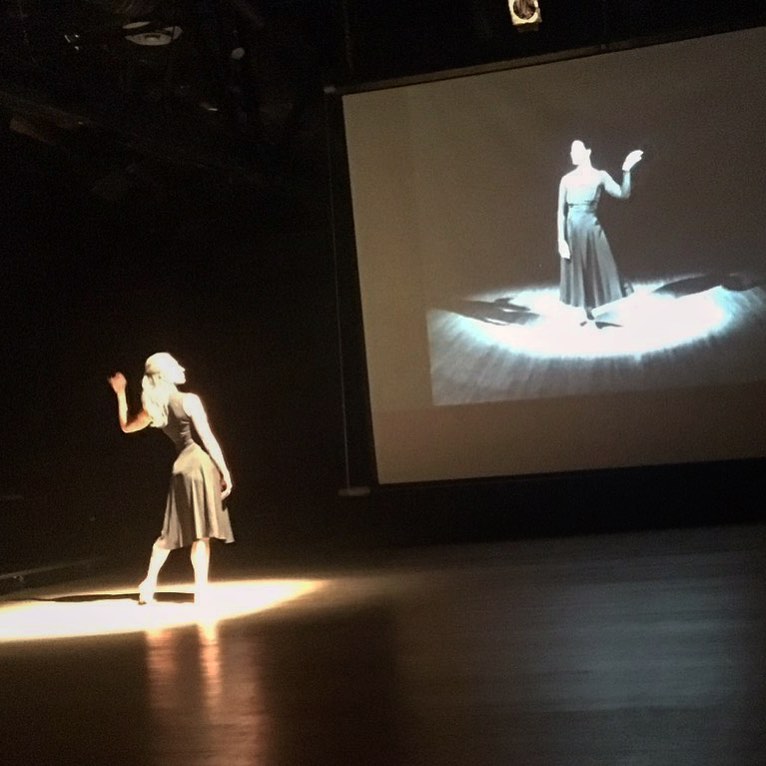

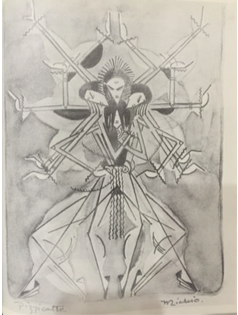

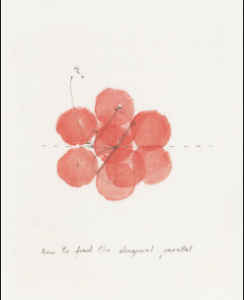

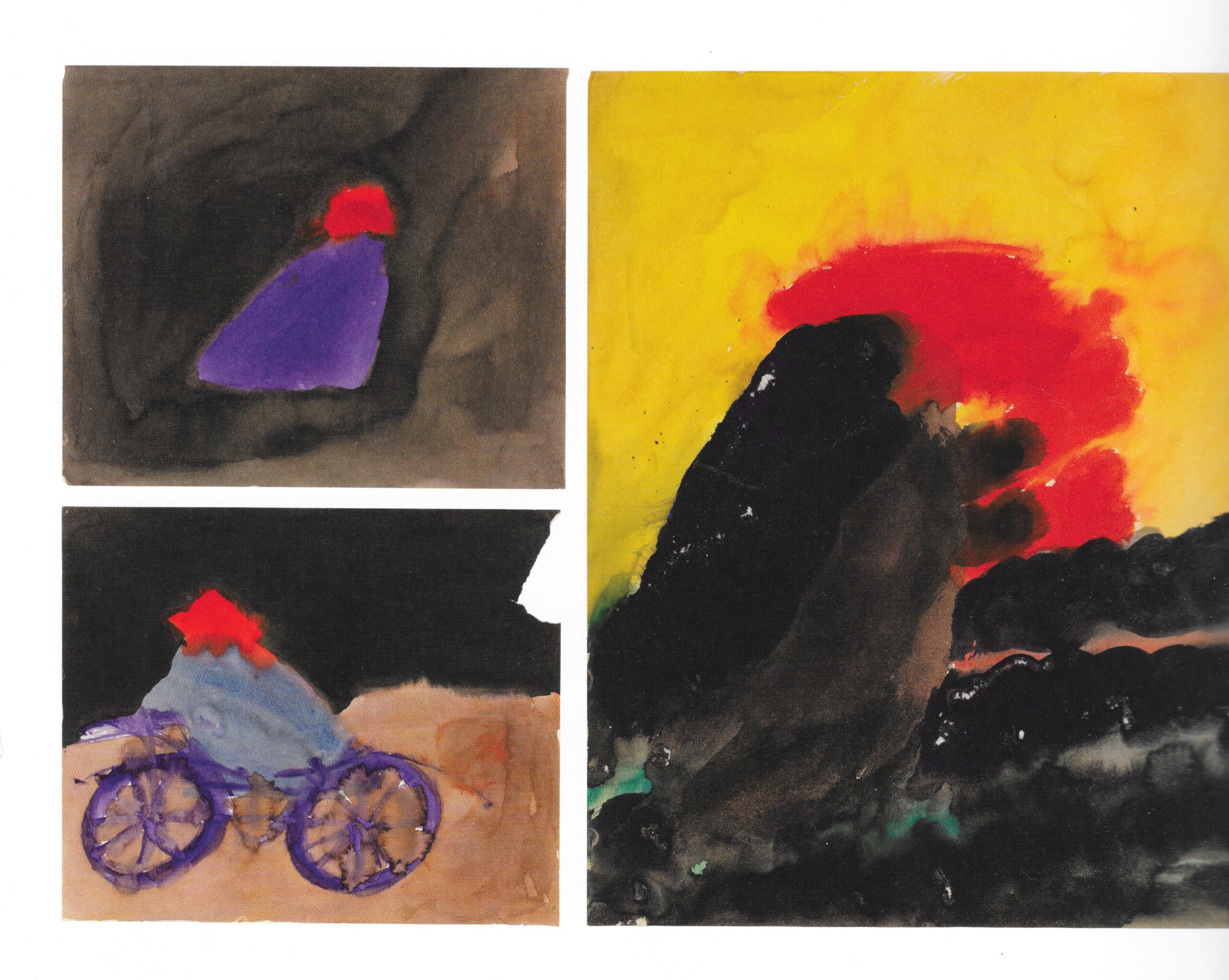

“Swing Is Here to Stay” from Ali Baba Goes to Town

Perhaps the greatest honor for Dr. LeGon, however, came posthumously. She has been enshrined in Zadie Smith’s 2016 novel Swing Time as a shadowy inspiration. The narrator, a young British woman, and her best friend Tracey become obsessed with LeGon, spending hours watching the faux African number “Swing Is Here to Stay” from Ali Baba Goes to Town (1937) on VHS. It’s a ludicrous dream sequence, with LeGon sashaying across the space, doing Charleston-like swinging, truckin,’ and stomping on her toes—all her own steps—wearing a grass skirt. She’s backed by musicians in mock African regalia, including Eddie Cantor in blackface. In the novel, both girls notice that LeGon looks uncannily like Tracey. Taking that resemblance as a sign, Tracey identifies with the tapper so obsessively that she creates the social media tag of truthteller_LeGon. When she applies to a top conservatory, Tracey prepares for the audition by learning every step of LeGon’s sequence from “Swing Is Here to Stay.” The judges proclaim her choreography to be totally original, and she gets in. Years later, as a beleaguered single mother living in the projects, Tracey names her first daughter Jeni. (Smith 213, 401)

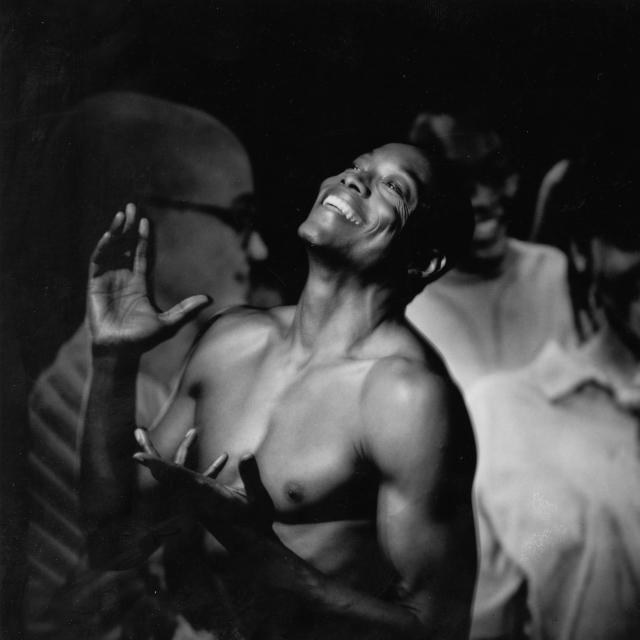

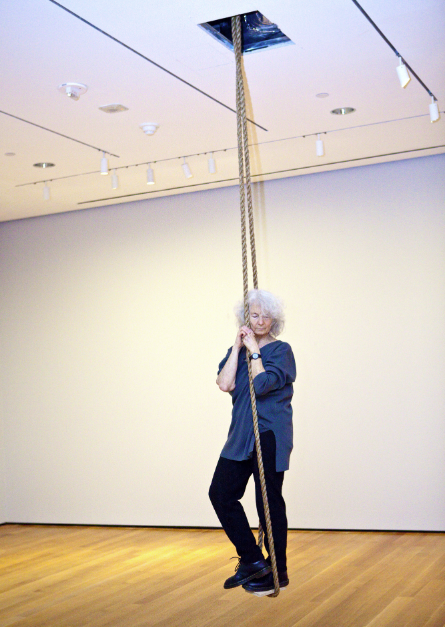

Jeni LeGon with Bill “Bojangles” Robinson

Also years later, the narrator (never given a name), while organizing a photo exhibit, chooses the photo of LeGon where she is springing up in a toe stand, with Bill Robinson kneeling at her side. She likes that shot because LeGon is above the famous male dancer. (What she doesn’t catch is that Robinson, although below her, is clearly telling the teenager what to do, with his finger pointing upward.)

While working on the photo exhibit, the narrator has burrowed into some research that shatters the girls’ fantasy of LeGon’s glamorous life. She learned that Fred Astaire had hobnobbed with LeGon and Robinson back in 1935, but by the time she played the maid in Easter Parade (1948), he ignored her. The narrator, whose voice is now conflated with that of Zadie Smith herself, explains her perception of what was going on in real life:

Astaire never spoke to LeGon on set, in his mind she not only played the maid, she was in actuality little different from the help, and it was the same with most of the directors, they didn’t really see her and rarely hired her, not for anything except maid parts… (Smith 428)

The narrator concludes that although the dancer was adored by her and her friend, Jeni LeGon is only a shadow, not a real person. And yet, on the final morning of the novel, she sees her old friend Tracey, still in bedroom slippers, dancing on her balcony with her three children. Even if LeGon was a shadow, her dancing was contagious.

That one of the best writers of our time fell under the tapper’s spell through video attests to LeGon’s power.

To come back to the non-fiction world, Jeni LeGon was embraced by the current tap community toward the end of her life. She was invited to several festivals and respected by a new generation. For Brenda Bufalino, a major dancer/choreographer who founded American Tap Dance Orchestra, LeGon was significant not only because she was one of the few women soloists in tap, but also, “She had a style that’s so delightful. This wonderful relaxed style, just swinging, more in line with the tap dancing of today.”

Oh, and in case none of the earlier clips made you fall in love with her, here is LeGon at 91, singing “Living in a Great Big Way,” charming as ever.

Footnotes

[1] For more on the Whitman Sisters, see The Royalty of Vaudeville by Nadine George-Graves.

[2] In 1992, Stephen Vaughn wrote this about Reagan’s leadership at SAG (1947–1952): “Reagan’s efforts for civil rights were secondary to his desire to combat communism and maintain a public image for the film industry.” For a complete discussion on Reagan’s changing position, see Vaughn’s essay, “Ronald Reagan and the Struggle for Black Dignity in Cinema, 1937–1953” in the Journal of Negro History, Vol. 77 No. 1, 1992.

[3] The all-Black show had started airing on a Chicago radio station in 1928. Although Amos ’n Andy was rated the most popular comedy show in radio history, the NAACP started objecting to it on the grounds of racial stereotyping in 1931. In 1953 CBS cancelled in response to those protests.

¶¶¶

Special thanks to the library staff at the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts.

Works Cited

Books and articles

Bernstein, Adam. “Jeni LeGon dies at 96; dancer was one of the first black women to become a tap soloist,” Washington Post Dec. 11, 2012.

Crowe, Larry, interviewer. Jeni LeGon (The HistoryMakers A2004.113), July 28, 2004, The HistoryMakers Digital Archive.

Ebert, Roger. “Jeni le Gon: The first black woman signed by Hollywood was livin’ and dancin’ in great big way,” rogerebert.com, January 23, 2013

George-Graves, Nadine. “Identity Politics and Political Will: Jeni LeGon Living in a Great Big Way,” in The Oxford Handbook of Dance and Politics, eds. Rebekah Kawal, Gerald Sigmund, and Randy Martin, eds, Oxford University Press, 2017.

Hutchinson, Pamela, “Hooray for Jeni LeGon: the Hollywood pioneer who danced ‘like a boy’” Sight & Sound, March 8, 2017.

Guide to the Jeni LeGon Papers, 1930s-2002, undated, Archives Center, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution.

Malone, Jacqui. Steppin’ on the Blues: The Visible Rhythms of African American Dance. University of Illinois Press, 1996.

Seibert, Brian. What the Eye Hears: A History of Tap Dancing. Farrar, Strouse and Giroux, 2015.

Smith, Zadie. Swing Time. Penguin Books, 2017.

Spaner, David. “I’m doing OK and I’m living in a great big way’: Jeni LeGon, often stole the spotlight dancing with the biggest stars of the 20th century.” The Province, Oct. 22, 2006.

Tinubu, Aramide. “The Hidden History of Lena Horne and ‘Stormy Weather.’” Zora, July 21, 2020.

Walling, Katie, ed. Tap Dancing Resources “Remembering Tap Dancer Jeni LeGon (1916-2012)”

Zoritch, George. Ballet Mystique: Behind the Glamor of the Ballet Russe: A Memoir by George Zoritch. Cynara Editions, 2000.

Film and video

Abbott, Dave. Global Village, The Tomorrow Channel, 2001. On Facebook.

Creighton, Gloria, host and producer. Interview with LeGon for Contact.

Rodgers Cable 4, West End NTV 1989.

Greschuk, Grant, director. Jeni LeGon: Living in a Great Big Way, documentary. Produced by National Film Board of Canada, 1999.

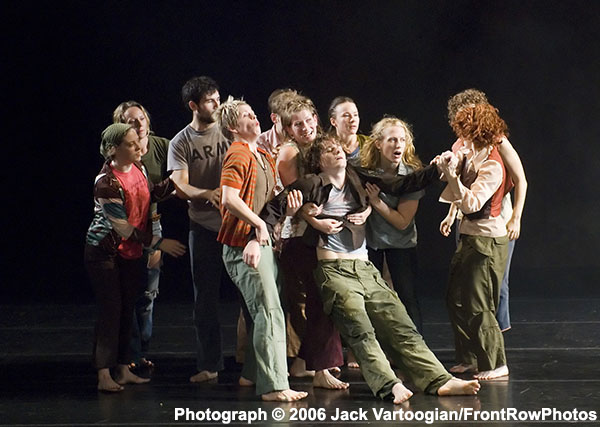

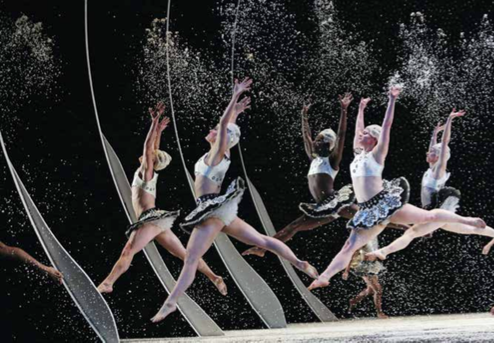

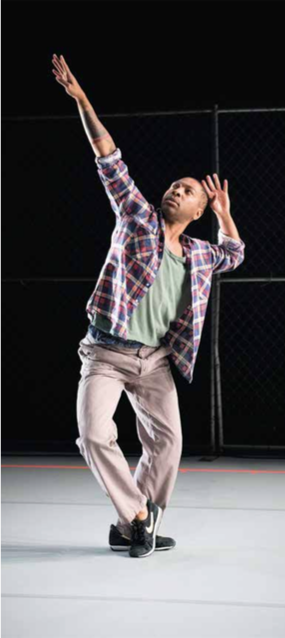

Uncategorized Unsung Heroes of Dance History 3

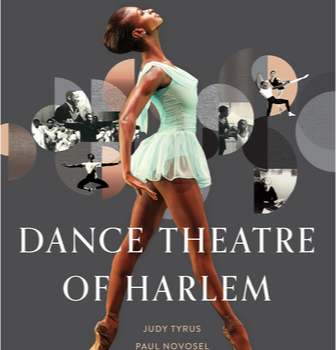

Dance Theatre of Harlem: A History, a Celebration, a Movement

Dance Theatre of Harlem: A History, a Celebration, a Movement Onstage With Martha Graham

Onstage With Martha Graham

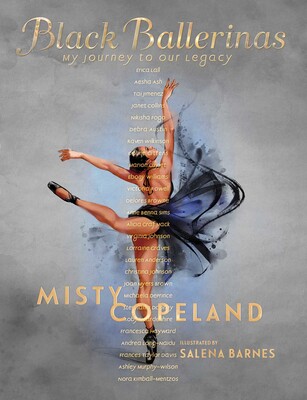

Black Ballerinas: My Journey to Our Legacy

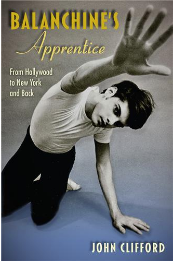

Black Ballerinas: My Journey to Our Legacy Balanchine’s Apprentice: From Hollywood to New York and Back

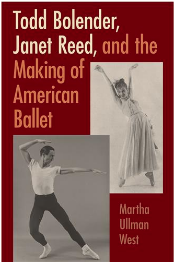

Balanchine’s Apprentice: From Hollywood to New York and Back Todd Bolender, Janet Reed, and the Making of American Ballet

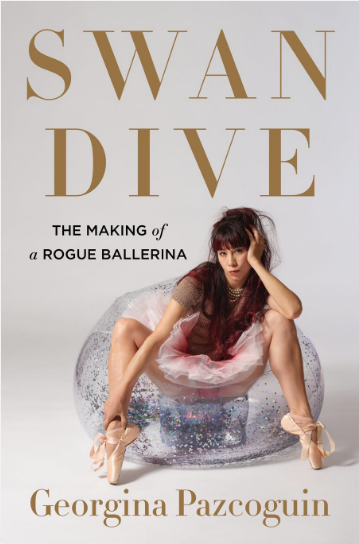

Todd Bolender, Janet Reed, and the Making of American Ballet Swan Dive: The Making of a Rogue Ballerina

Swan Dive: The Making of a Rogue Ballerina A Body in Fukushima

A Body in Fukushima

Center Center: A Funny, Sexy, Sad Almost-memoir of a Boy in Ballet

Center Center: A Funny, Sexy, Sad Almost-memoir of a Boy in Ballet Dance Spreads Its Wings: Israeli Concert Dance 1920–2010

Dance Spreads Its Wings: Israeli Concert Dance 1920–2010 Physical Listening: A Dancer’s Interspecies Journey

Physical Listening: A Dancer’s Interspecies Journey

Her 1949 appearance at Carnegie Hall garnered a bewildered review from Nik Krevitsky in Dance Observer (Louis Horst’s publication). The program had the look of a casual rehearsal. He ended by saying, “There was an arrogance in this studied naivete of the April 24th concert that shows no sign of progress in one of our most distinguished young dancers.” (Krevitsky 83)

Her 1949 appearance at Carnegie Hall garnered a bewildered review from Nik Krevitsky in Dance Observer (Louis Horst’s publication). The program had the look of a casual rehearsal. He ended by saying, “There was an arrogance in this studied naivete of the April 24th concert that shows no sign of progress in one of our most distinguished young dancers.” (Krevitsky 83)

It’s a strange, unsettling thing, but disaster can be visually beautiful. In a monumental new book called

It’s a strange, unsettling thing, but disaster can be visually beautiful. In a monumental new book called

[I wrote this article for the August, 2000 issue of Dance Magazine. Reprinted with permission.]

[I wrote this article for the August, 2000 issue of Dance Magazine. Reprinted with permission.]