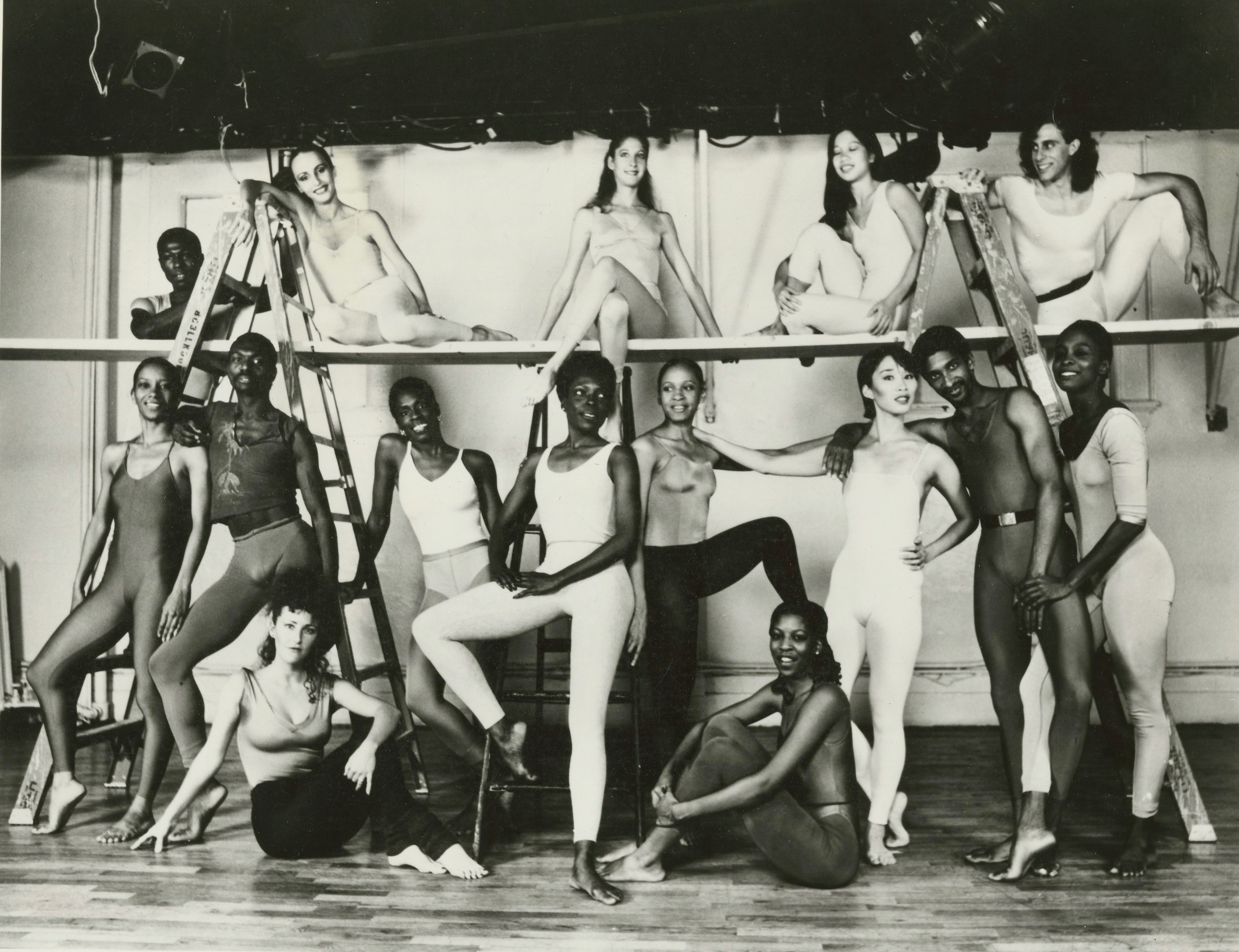

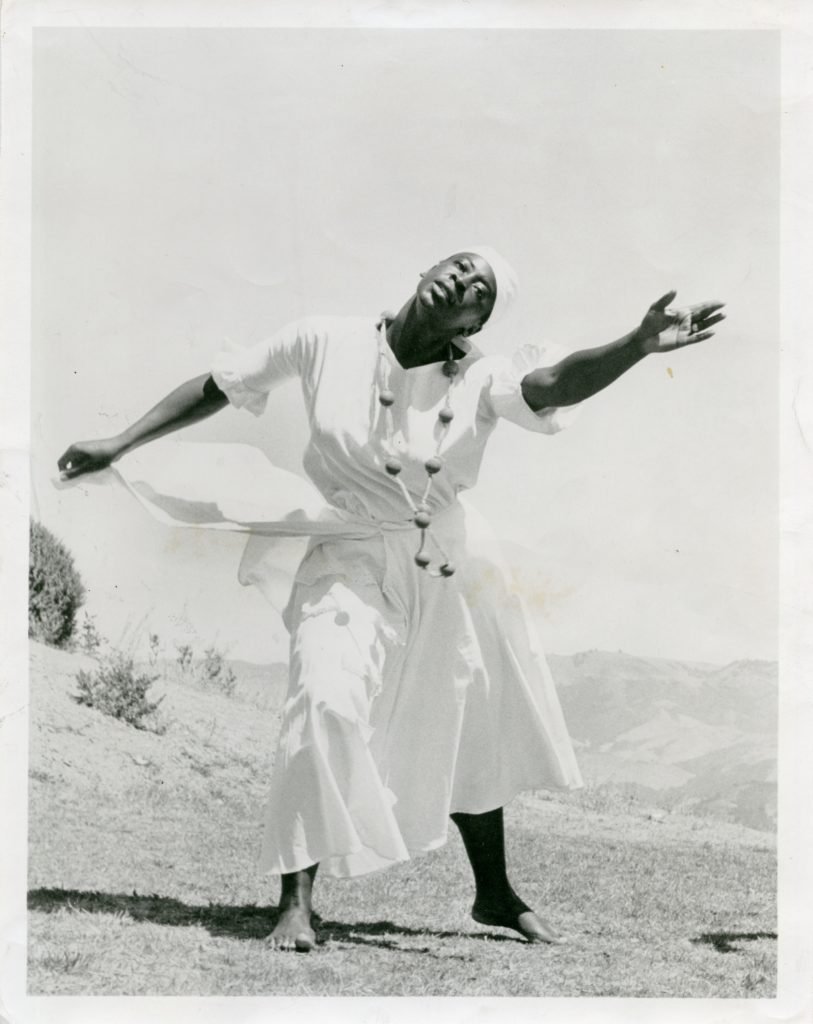

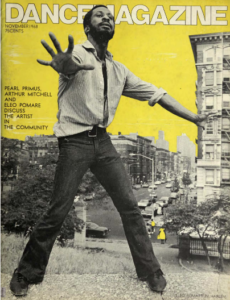

Photo by Martinus Anderson

Who was the first African American to start a modern dance company? Who was the first Black performer to be cast in a Metropolitan Opera production? And which pioneer of American modern dance died tragically young at 26?

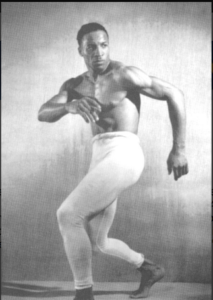

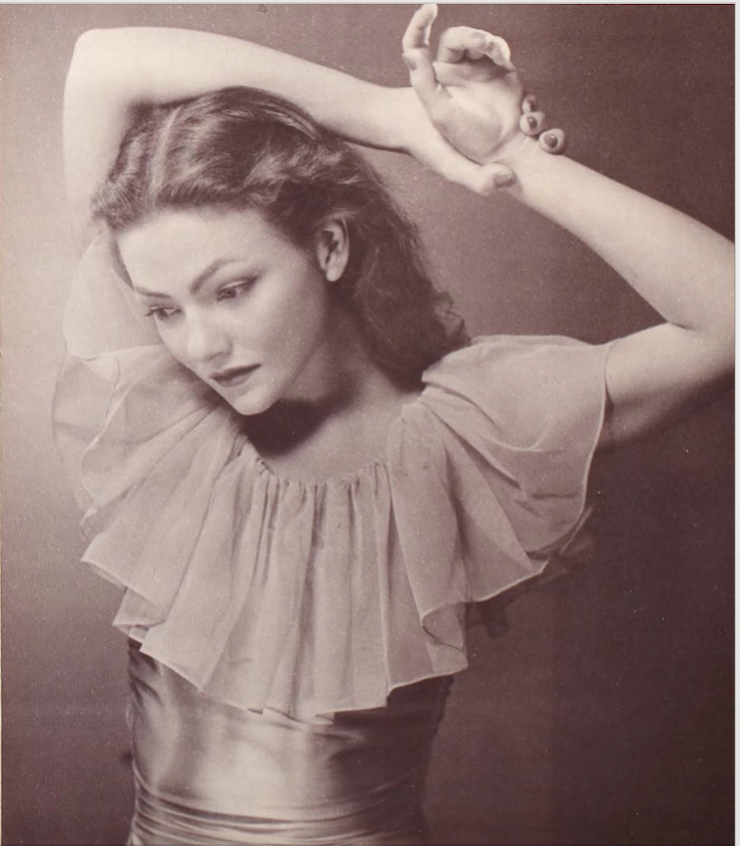

The answer to all three questions is Hemsley Winfield. Starting out as an actor who choreographed for plays, he extended his abilities to directing, producing, teaching, performing, and choreographing. He shone as a dancer, garnering adjectives like “startling” and mesmerizing.” In the last four years of his life he made valiant efforts to sustain a Black modern dance company. This was during the Harlem Renaissance, which celebrated Black literature, visual art, music and theater.

We have very little in the way of photographs or descriptions of Winfield as either a dancer or choreographer. We do know he was tireless in getting gigs for his group, whether it was a theater group or dance group. And we have evidence from reviews that he was promising, courageous, and charismatic.

Winfield was born in Yonkers, New York, and attended public schools. His father co-owned a construction business and his mother was a nurse, educator, and playwright. He was athletic as a child. His parents owned their own home, and he lived with them his whole life, so he was relatively insulated from the poverty that befell many in the Depression.

All God’s Chillun Got Wings, with Paul Robeson and Mary Blair c. 1924

Leadership came naturally to Winfield. Almost as soon as he became an actor, he also became a director. He trained with the National Ethiopian Art Theatre School, which offered classes in Isadora-like “esthetic dancing” (Perpener 30) as well as in acting. At the age of 17, he found himself directing an offshoot group called Mariarden Players that seems to have functioned as a student group (Neal 11-12). That summer, he landed a minor role in Eugene O’Neill’s All God’s Chillun Got Wings, a play about a mixed-race couple starring Paul Robeson, at the Provincetown Playhouse (Perpener 29). A photo of the white actress Mary Blair kissing the hand of Robeson circulated in the press, igniting a prolonged uproar that included a bomb threat (Duberman 58-59), which can’t have been lost on the young Winfield.

At 18 Winfield started directing his own troupe, the Sekondi Players, as part of the “little theatre” movement, analogous to community theater, that took hold around the country. He later incorporated the Sekondi players into his larger group, the New Negro Art Theatre (Neal 31). After directing many productions in small theaters in and around New York City, he was called an “outstanding leader” in the little theatre movement. As Joe Nash said, “Filled with the hype and hope fostered by the proliferation of the “new”—New Masses, New Era, New Science, New Woman—this group of dancers was anxious to wrestle with the negative images popularized by decades of minstrelsy to create a New Negro dance” (Nash, Free to Dance).

But let’s go back.

Lulu Belle

While directing his theater group, Winfield often took acting roles in other productions. When the controversial Lulu Belle, written by white men (Edward Sheldon and Charles MacArthur) and produced by a white man (David Belasco), opened at the Belasco Theater in February 1926, Winfield played the minor character of Joe. In a cast of 115, 100 were black, but the top roles went to whites who wore blackface. The character Lulu Belle was a Black woman who was sexually provocative, wantonly independent, and unfaithful. Like Carmen, she ended up murdered. The third act took place in a fictional gay nightclub where Lulu Belle had a dancing gig. So, although there were no gay characters, Lulu Belle glamorized what was called the Pansy Craze.

A scene from Belasco’s Lulu Belle, probably in Act I.

White critics and Black critics had different reasons for not liking the play: Black critics found it “disturbing” for its appalling portrayal of Harlem, white critics found it immoral. But theater goers—most of them white—came flooding in. As scholar James F. Wilson as written, “Harlem’s appeal for whites was its promise that all regulations of polite society would indeed be broken.” He called Lulu Belle “one of Broadway’s biggest hits of the 1920s” (Wilson 81-82).

Another scene from Lulu Belle. Belasco’s settings were always as realistic as possible.

According to Wilson, the character of Lulu Belle was subversive for more reasons than her loose sexuality:

(T)he hypersexual Lulu Belle is controversial not for her erotic desire, but for her representations of class and race. As responses to the play and drag balls lay bare, the visible homosexual (that is, the cross-dressed man or woman) and the sexually unrestrained black woman, both associated with the working class, were particularly contentious figures to the African American communities in the Harlem Renaissance. They each posed a perilous threat to the advancement of the race because of their “low-class” morality, and mocked the ideals of the middle-class family toward which the communities strove (Wilson 81-82).

The tension between the goals of the elder artists and the wishes of the younger ones continued throughout the Renaissance.

Lulu Belle ran for 461 performances on Broadway, providing Winfield and many other Black performers with thirteen months of work (Playbill).

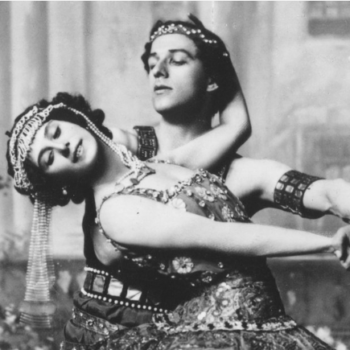

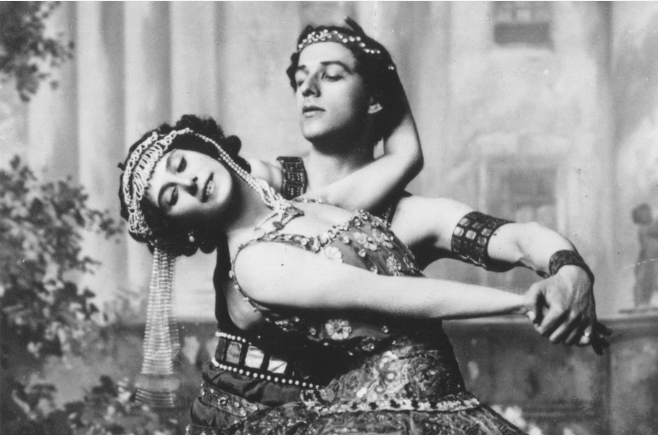

Salome

Perhaps it was Lulu Belle that gave Winfield a taste for provocative plays written by white men. His next project was to direct Oscar Wilde’s Salome for his own group, the New Negro Art Theatre. At that time Wilde’s play was enjoying coast-to-coast popularity, partly because of the Orientalist fad and partly for the opportunity it afforded female actors. As Black dance scholar John Perpener has pointed out, the role had been played by Ida Rubinstein, Loie Fuller, and Maud Allen (Perpener 34). In fact, Salome had been produced by the original, Chicago-based Ethiopian Art Theatre in 1923. [The New York–based National Ethiopian Art Theatre School, where Winfield trained, started in 1924.]

Winfield first directed his own version at the Philipsburgh Hall in Yonkers in 1926. Two years later, his company performed it at the Alhambra Theater, a major Harlem hot spot, at midnight.

Although the idea of the Harlem Renaissance was to cultivate Black artists, there was also a feeling that a “serious” play meant a play written by a white person (Poueymirou 204). That if Black actors could play roles not designated as Black characters, the play would be deemed more universal (Poueymirou 202). And yet what appealed to the younger generation of Harlem Renaissance artists about Wilde’s play was its sensuousness and decadence. They didn’t want to have to be “high-minded” all the time.

When the production returned to Yonkers, the leading lady took sick and Winfield stepped in to dance Salome himself. He continued to dance the role when, in 1929, the production moved to the Cherry Lane Theatre, located in Greenwich Village, which was, even back then, a haven for gay men. Apparently Winfield wore not much more than a beaded curtain (Perpener 34) and reveled in the movement. One of his dancers, Richard Bruce Nugent, remembers him in that role:

He, for instance, did a show . . . in which he played the role of Salome. And, well, it sounds like a laugh, but it wasn’t a laugh because he was Salome. There was nothing camp about it. He just was Salome. He was absolutely dedicated to what he was doing (Perpener 35).

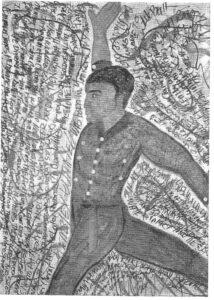

Nugent became so obsessed with Winfield in the Dance of the Seven Veils that he made a series of drawings depicting Salome dancing.

Nugent’s drawing of Salome dancing, late 1920s

Perpener and others have opined that Winfield’s performing of Salome turned him toward concentrating on dance rather than theater (Perpener 33-34). But something else was happening too.

Run-in with Du Bois

The great civil rights leader W. E. B. Du Bois, the inspiration behind the Harlem Renaissance, published an article in 1926 in The Crisis, the magazine he co-founded and edited. In this article, he laid down what Black theater should be:

The plays of a real Negro theatre must be 1. About us. That is, they must have plots which reveal Negro life as it is. 2. By us. That is, they must be written by Negro authors who understand from birth and continual association just what it means to be a Negro today. 3. For us. That is, the theatre must cater primarily to Negro audiences and be supported and sustained by their entertainment and approval. 4. Near us. The theatre must be in a Negro neighborhood and near the mass of ordinary people (Perpener 28).

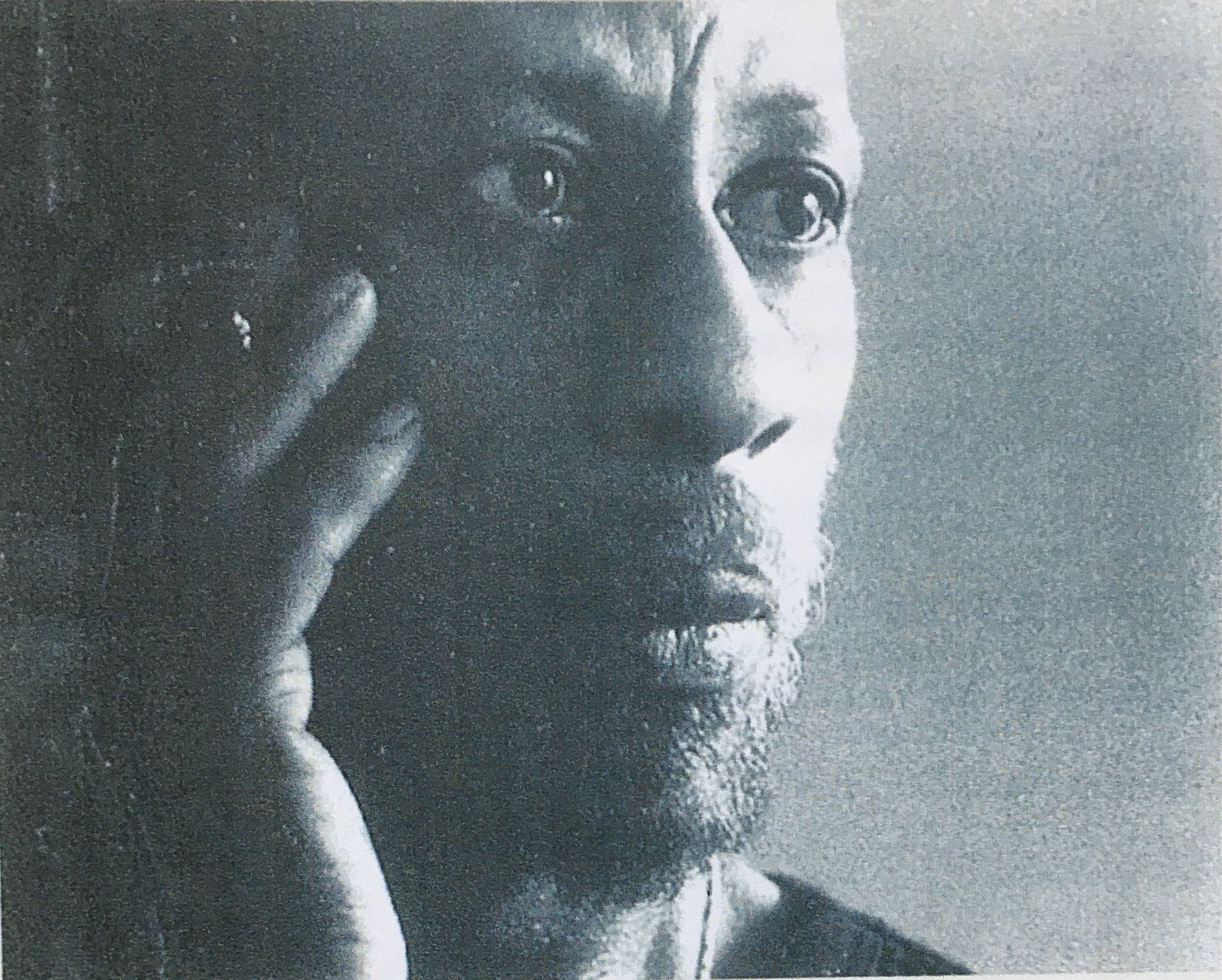

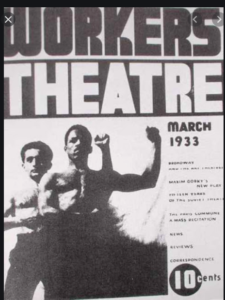

The Crisis, Jan. 1927 issue, art by Aaron Douglas

Along these lines, Du Bois established his own group, the Krigwa Players, in the basement of the Harlem branch of the New York Public Library on 135th Street (later named the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture). And there is evidence that the Krigwa Players had actually collaborated with Winfield as an actor and director in a program of one-act plays (W. E. B. Du Bois Papers).

According to correspondence revealed by Winfield biographer Nelson D. Neal, Winfield and Du Bois were planning, starting in January 1927, to share the basement space for rehearsal and performance. Apparently Winfield’s group did perform there in February. Then, in August, the Amsterdam News printed an item announcing that the New Negro Art Theatre, directed by Winfield, would move into the Harlem library basement “permanently.” Du Bois hit the ceiling. He had not extended the space on a permanent basis. When told that the item was in error, he was not assuaged. On September 12, 1927, he sent a letter to the librarian threatening to withdraw the Krigwa Players if they went ahead with (or continued with) housing Winfield’s New Negro Art Theatre (which now contained the Sekondi Players). The reason? “They are not at all up to our standard.”

When you consider Du Bois’ definition of Negro Theatre, it’s easy to see why Winfield didn’t measure up: his choice of playwrights were mostly white: Oscar Wilde, Eugene O’Neill, Ridgely Torrence. At that point, Winfield had not yet done his drag act in Salome, but he had produced Wilde’s play in Yonkers and as a radio play. This may have bothered Du Bois, as he considered the Wildean aesthetic decadent, thus undermining the goals of the Harlem Renaissance (Wirth in Nugent 47).

I suspect that his brush with Du Bois steered Winfield away from theater and toward dance. Perhaps he envisioned greater independence as a dance artist. After all, no one was laying down the rules for Negro dance.

Shunned by Harlem Renaissance Journals

While the Amsterdam News called Winfield’s performance as Salome “startling” and “worth seeing,” the official Harlem Renaissance mouthpieces, i.e. The Crisis and Opportunity (the publication of the National Urban League), ignored it, possibly reflecting Du Bois’ influence. Harlem Renaissance scholar Margaux Poueymirou connects the shunning of Winfield’s Salome with the Renaissance elite’s disdain for the gay culture within Harlem:

Their silence is telling indeed . . . their unwillingness to acknowledge Winfield’s performance was consistent with their reaction to the aesthetic culture that now contained a writer like Wilde and a play like Salome . . . Winfield’s performance of Salome may have suggested the culture surrounding Harlem’s notorious drag balls of the 1920s and early 1930s, spectacles in themselves that drew blacks and non-blacks and gays and straights together . . . But the critical reception of the New Negro Art Theatre’s production of Salome also recalled earlier discourses that wove in and out of “Salomania” where Salome was a thing to be gazed at, a fascination that both reflected and contributed to the period’s interest in Orientalia, above all a trope of otherness which, in Winfield’s case, unfolded in relation to race, gender and sexuality and the idea of the self as always self-fashioned (Poueymirou 215).

Opportunity, Feb. 1926, art by Richard Bruce Nugent

Winfield’s familiarity with queer Harlem likely stemmed from his friendship with Nugent, who later became a celebrated gay writer, his writings collected in Gay Rebel of the Harlem Renaissance. In a manuscript for a novel titled Geisha Man, Nugent writes about an all-male party where everyone was drinking: “The men became amorous, and public caresses became more and more frequent. Hemsley was dancing nude in the front room” (Nugent 96).

Tantalizing. Was there any basis in reality or was this pure fiction? Remembering that Nugent admired Winfield’s scantily clad portrayal of Salome to the point of obsession, I find this vision of Winfield to be equally believable as memory or fantasy. Nugent frequently attended drag balls at the Savoy Ballroom and Rockland Palace (Cass) and could have easily been accompanied by Winfield—or could have imagined him being present.

Henry Louis Gates, in his Foreword to Gay Rebel of the Harlem Renaissance, writes, “The list of gay and lesbian African Americans is impressive and long, but it is surely headed by Bruce Nugent. Nugent was boldly and proudly gay. He was the most openly homosexual of the Harlem Renaissance writers” (Gates in Nugent, xii).

Playbill for Fast and Furious, Sept. 1932

Another event that suggests Winfield’s familiarity with Harlem’s queer world was his role in “Pansies,” one of the thirty-seven skits in the over-stuffed, ill-fated revue Fast and Furious. With ninety cast members, twenty-four musicians, and nine sketch writers including Zora Neale Hurston and comedian Jackie (later “Moms”) Mabley—both of whom also performed—Fast and Furious lasted only one week at the New Yorker Theatre in September 1931. Winfield danced, acted, and sang, taking part in “Jacob’s Ladder,” “Boomerang,” and “Dance of the Moon,” in which he danced alone, covered in bronze. But the scene that was called the funniest was the Pansies skit (Neal 79), with the song “Pansies on Parade” by Porter Grainger. This no doubt parodied the flamboyant ritual at drag balls where each beauty contestant would strut their stuff before the competition (Wilson 86). Sometimes they’d be named for a flower. In Fast and Furious, the Flowers included Orchid, Violet, Lily, Daffydill [sic], and a quartet of Dancing Pansies. Winfield, however, was not a Flower but was cast as the Young Man (Neal 103–107).

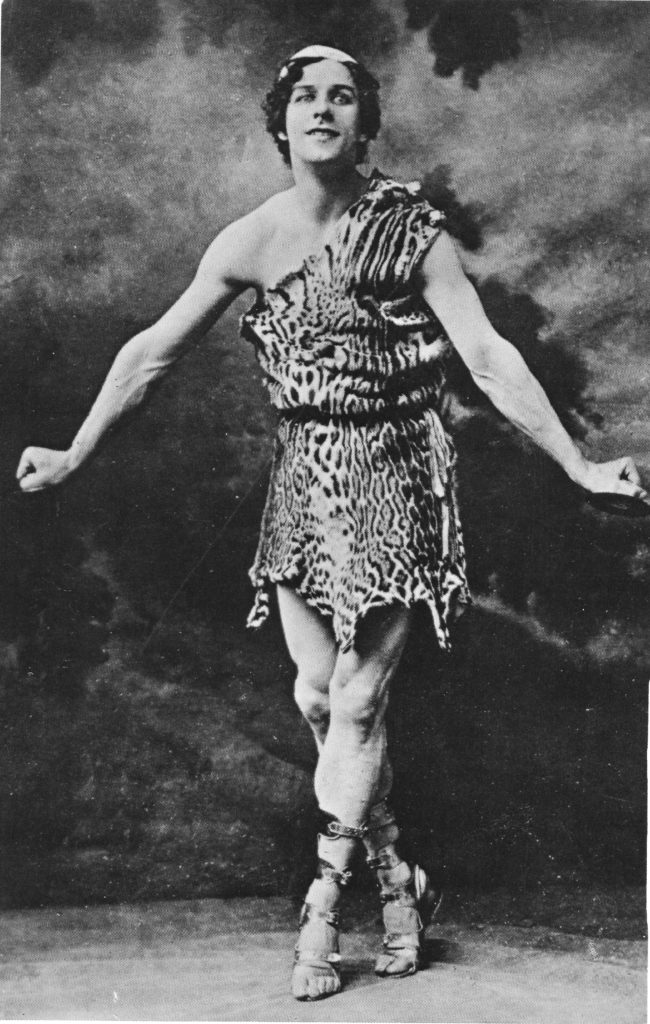

The First Black Modern Dance Company

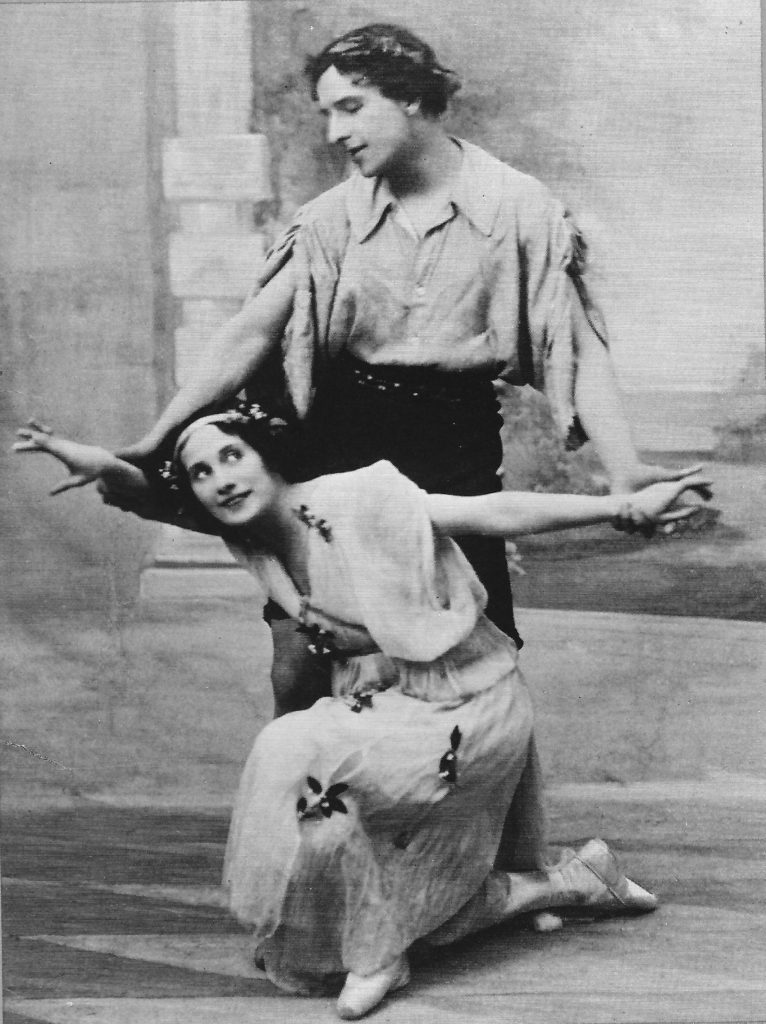

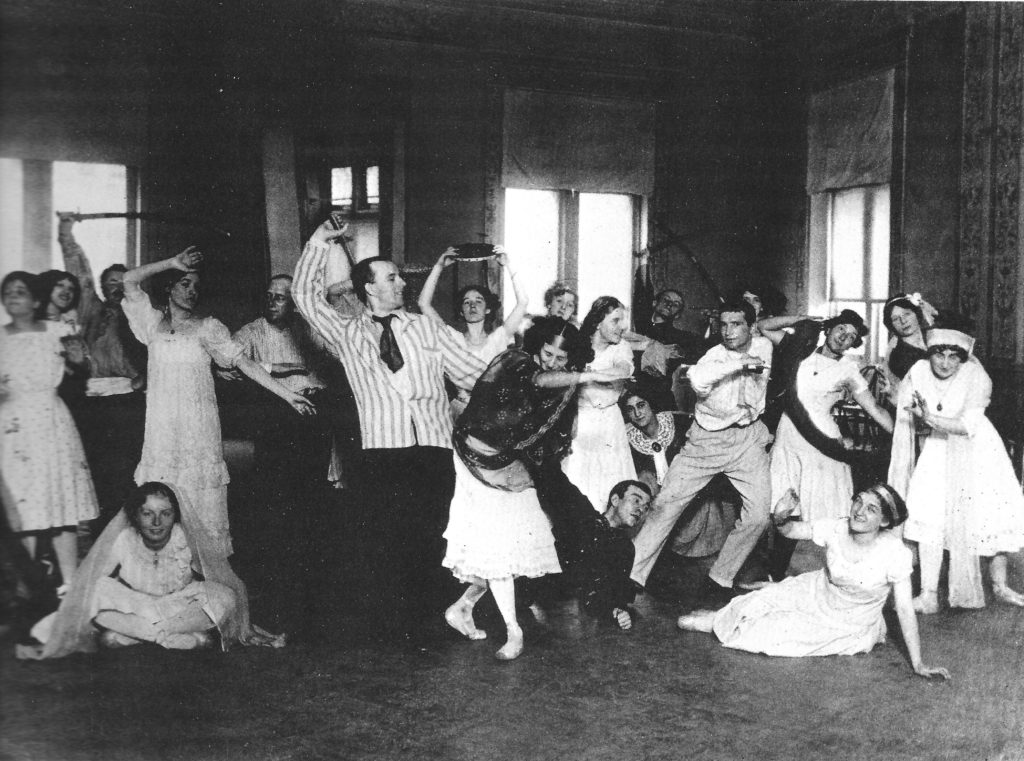

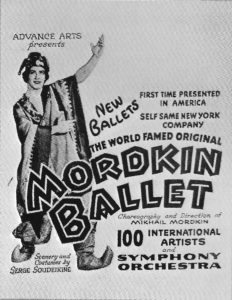

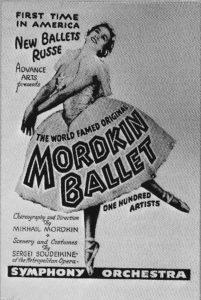

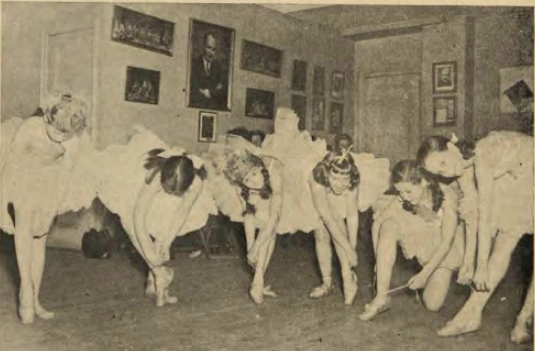

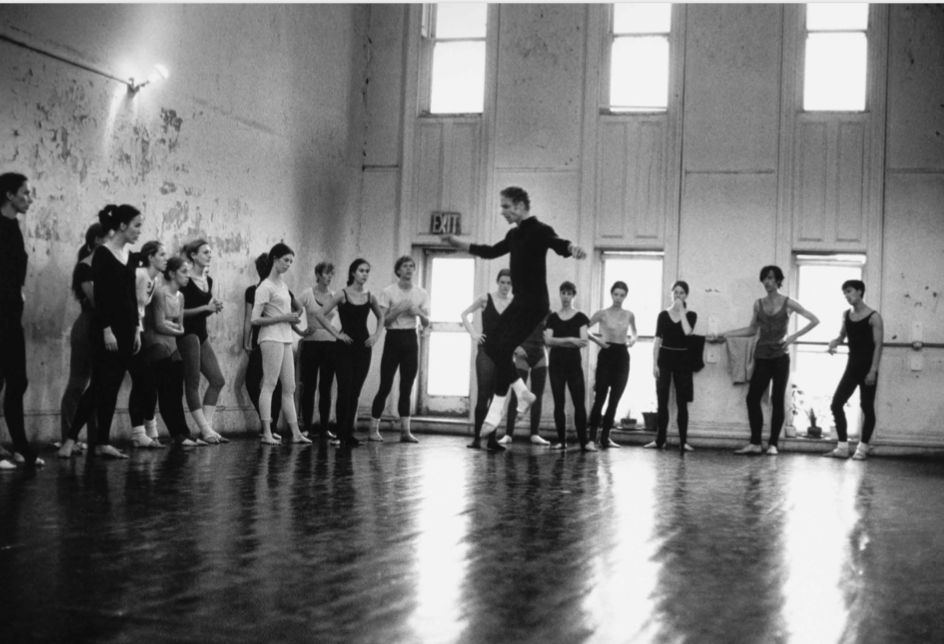

On March 6, 1931, Winfield debuted his dance group, calling it the Bronze Ballet Plastique. The name was probably influenced by Mikhail Mordkin, with whom he was studying. A former Bolshoi Ballet star whose company made possible the formation of Ballet Theatre, Mordkin often used the word “plastique.” It’s a word that’s been popular in Russia to this day, to describe a sinuous kind of expressiveness. Winfield may have also studied with Helen Tamiris, who taught in Harlem, and he may have seen early performances by the German expressionist dancer Harald Kreutzberg or by Ted Shawn (Perpener 41).

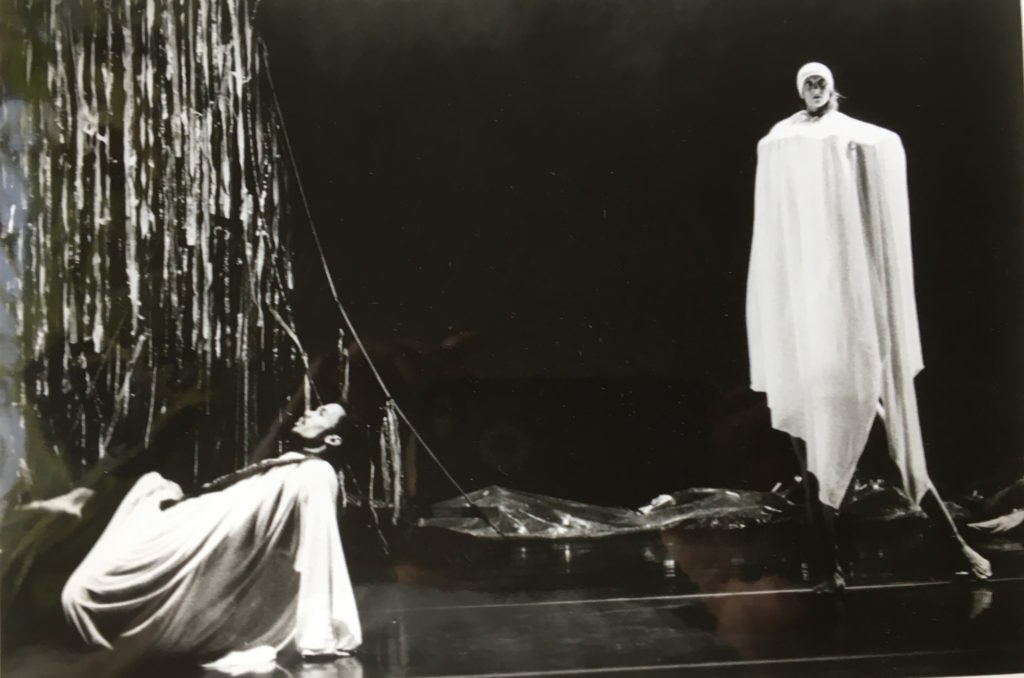

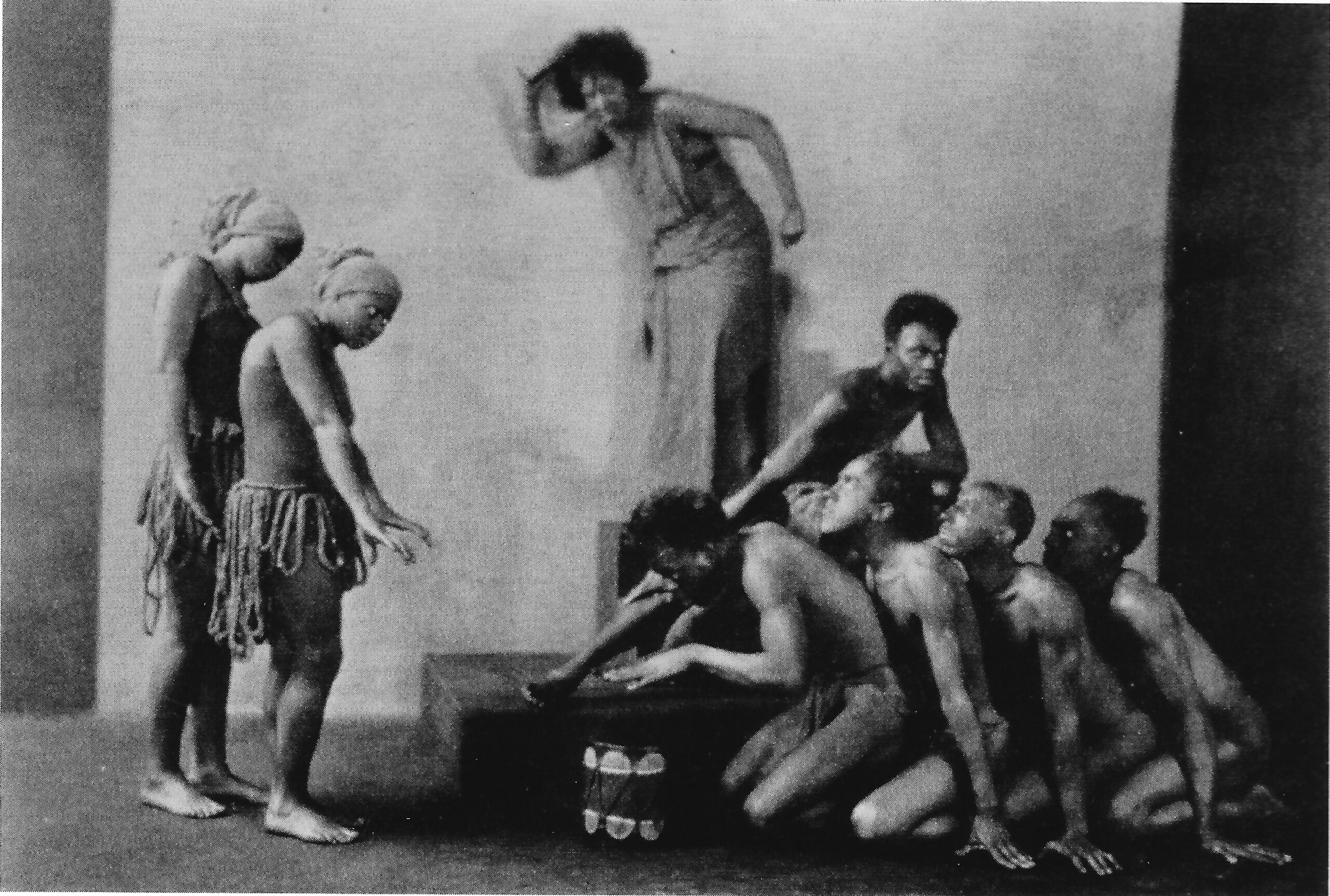

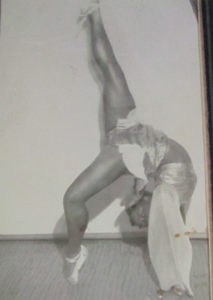

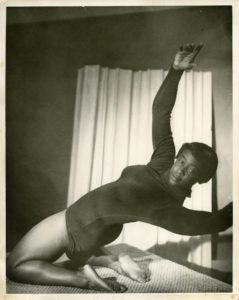

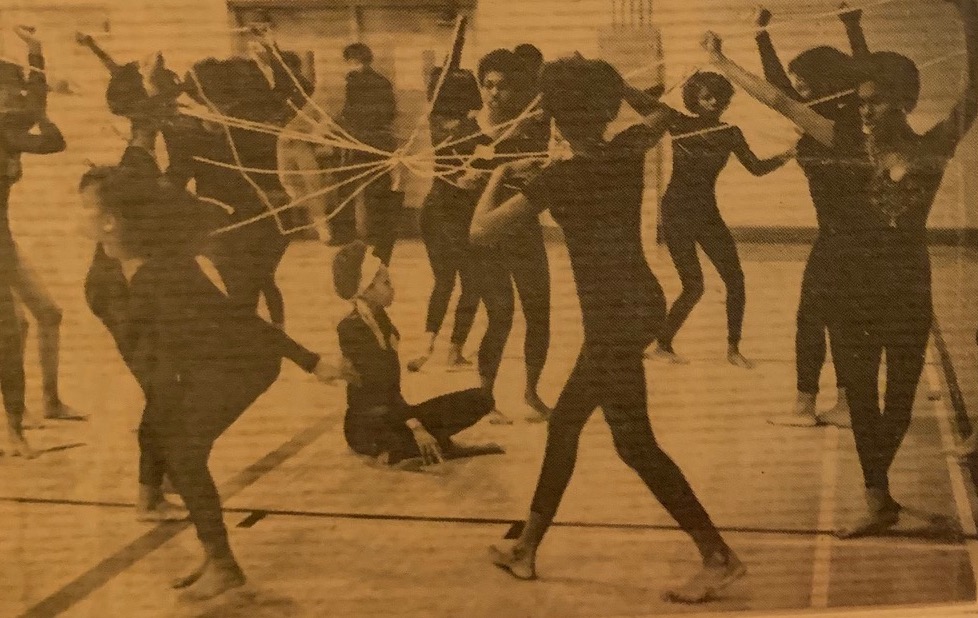

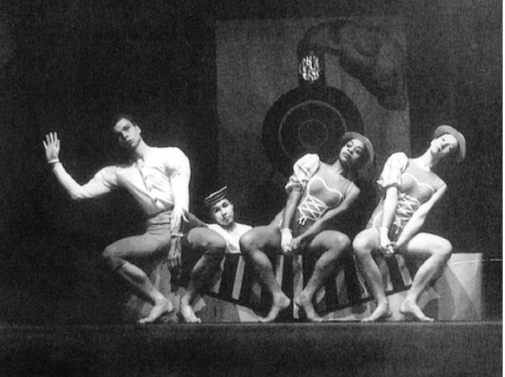

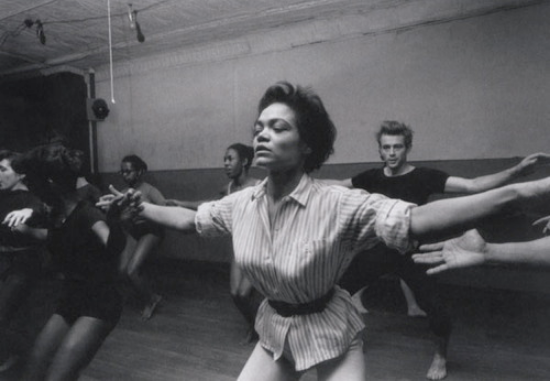

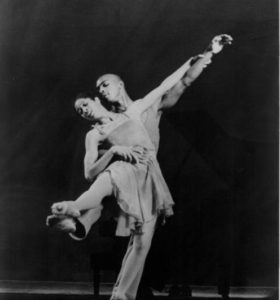

Hemsley Winfield, below center, in his Life and Death 1931 Joe Nash Collection

The Bronze Ballet Plastique gave one performance at the Saunders Trade School in Yonkers as a benefit for the Colored Citizens Unemployment Relief Committee. The program of works choreographed by Winfield included the following, with my shortened versions of Winfield’s own notations (Neal 88–95):

![]()

![]()

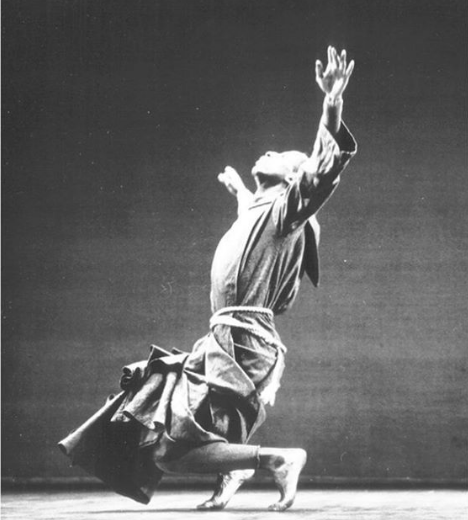

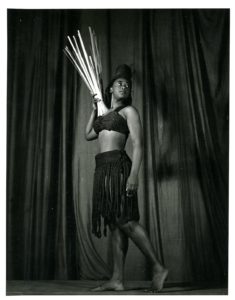

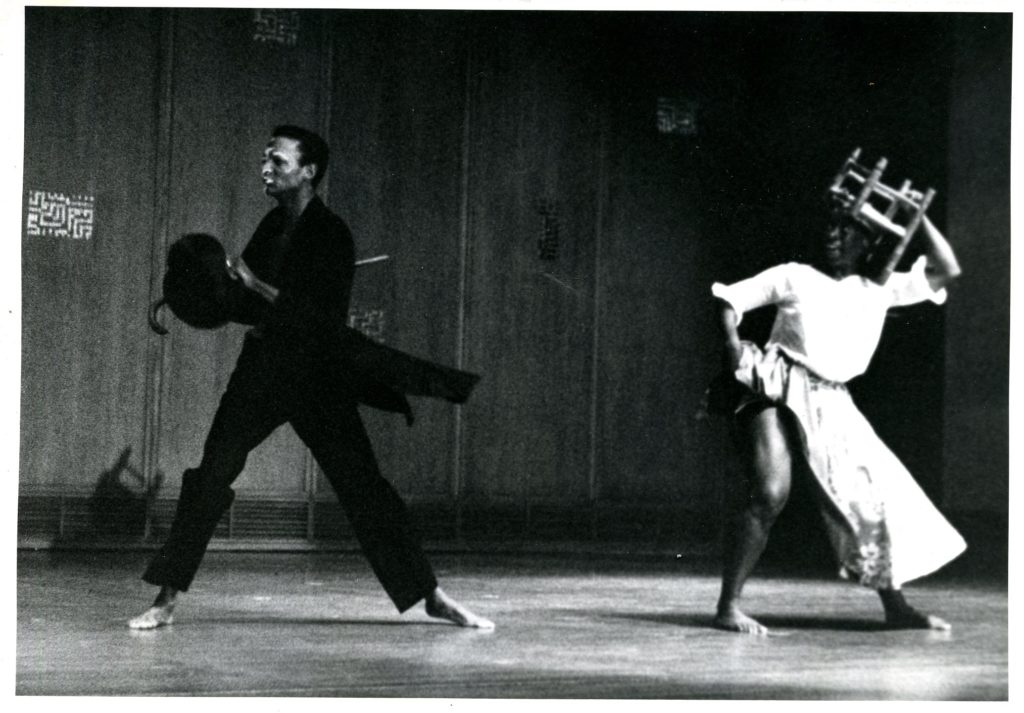

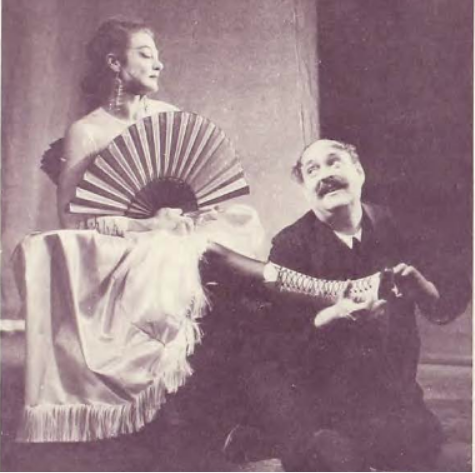

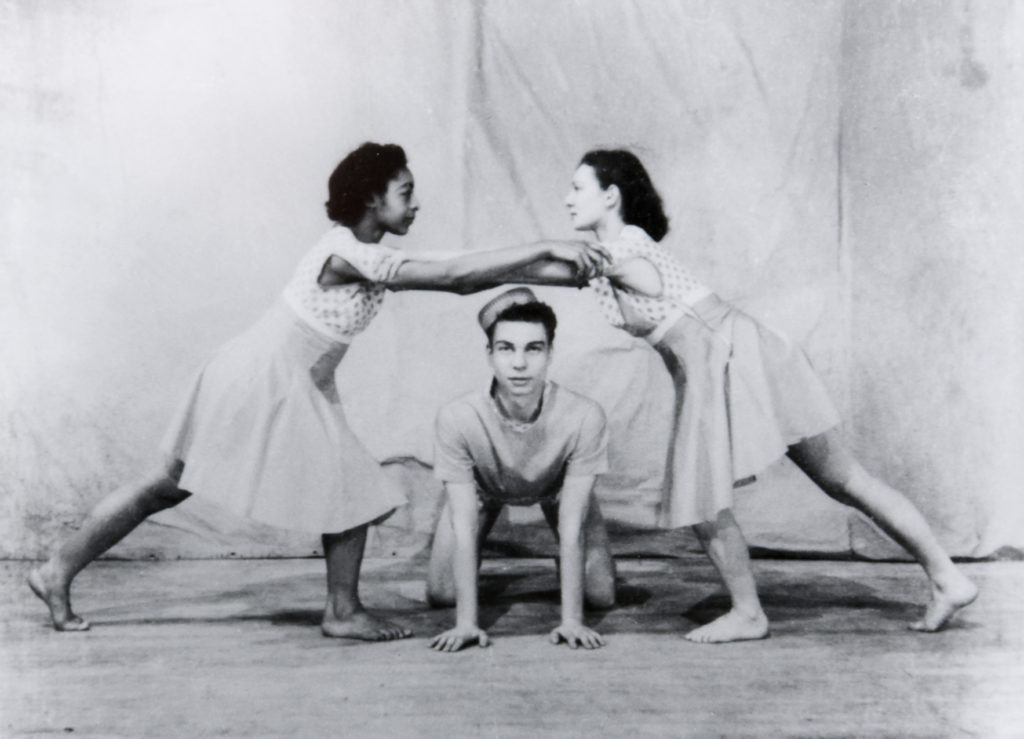

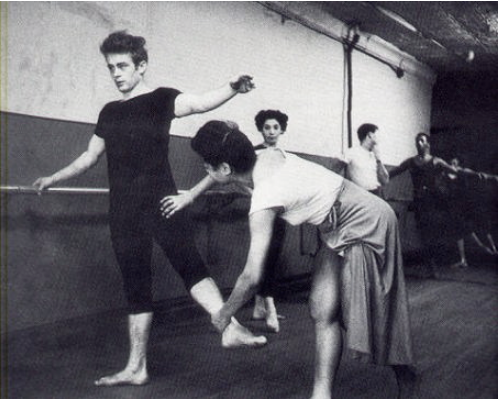

Jungle Wedding with Winfield and Frances Atkins 1931, Joe Nash Collection

![]()

![]() Jungle Wedding: a ritual in Africa in which a chief gives his daughter to a prince, tom-toms beating, with authentic African masks and costumes.

Jungle Wedding: a ritual in Africa in which a chief gives his daughter to a prince, tom-toms beating, with authentic African masks and costumes.

Prohibition: a man drinks himself into a stupor. The police enter, beat the man until they, the police, are exhausted. The man rises, discovers his old gin bottle, drinks, and laughs hysterically.

Life and Death: (originally a scene from Wade in de Water, a play produced as a pageant by his mother, Jeroline Hemsley): Life is a solo figure in the center of the stage. Death, a group of fifteen men, swoops down from the four corners of the earth and pours upon Life deadly diseases. Life fights desperately, freeing itself momentarily. Death claws Life in a mass movement, rising in triumph.

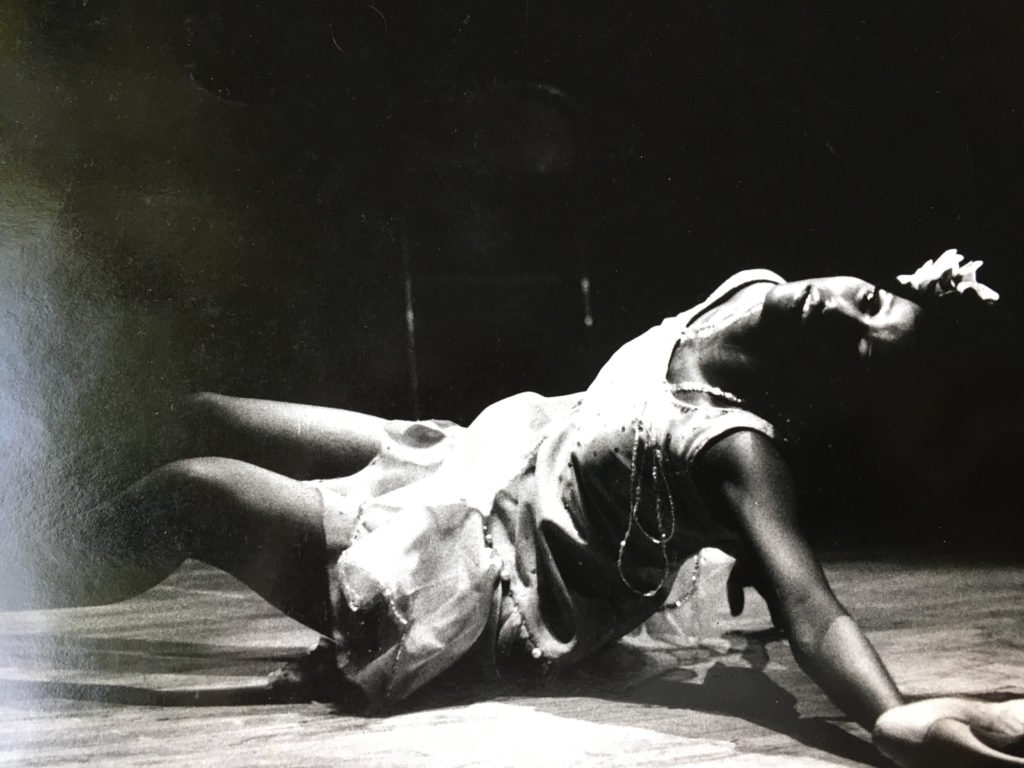

St. James Infirmary: Eight figures, one at a time, come downstage in silence to perform one step, e.g., a kick step, a shake, a Charleston. Each time the rhythm starts in the feet and continues through the body to the fingertips, which then stiffen. A girl enters, doing “modernistic” movements. The men place her on a hearse, cover her with a red cloth, and bury her.

Negro: A sole figure dances to slow blues that accelerates to become barbaric and more negro [sic].

Work Song: A chain gang. A guard strikes a worker who is not working fast enough. That worker ends up tugging on the guard’s legs.

From his own notes, these seem like harshly stereotypical depictions. Even more reason to wonder how Winfield might have evolved as an artist.

After that first performance, he changed the name of the group, re-embracing the New Negro but adding the word “dance,” so it became the New Negro Art Theatre Dance Group (Neal 68). I suspect that the name change also resulted from having second thoughts about including word “ballet.” Winfield was seeing early, as yet unnamed modern dance during that period, and he may have felt more aligned artistically with this new form. Mary Wigman was touring the United States from 1931 to 1933; Harald Kreutzburg was touring, Some of Winfield’s work, certainly the photo of Life and Death, is reminiscent of the group dynamics of German Ausdruckstanz.

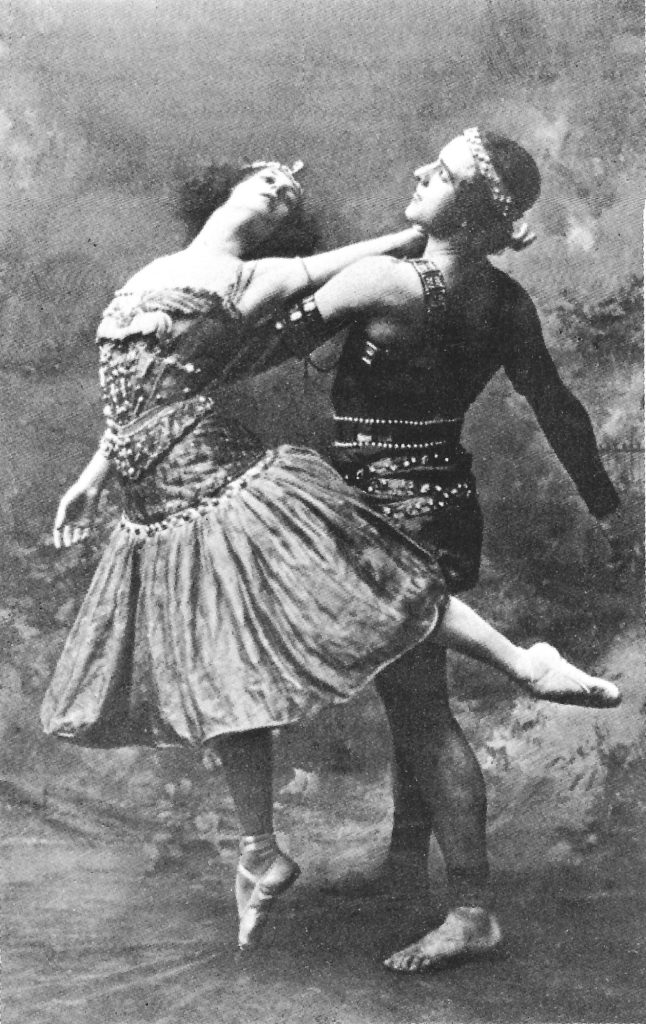

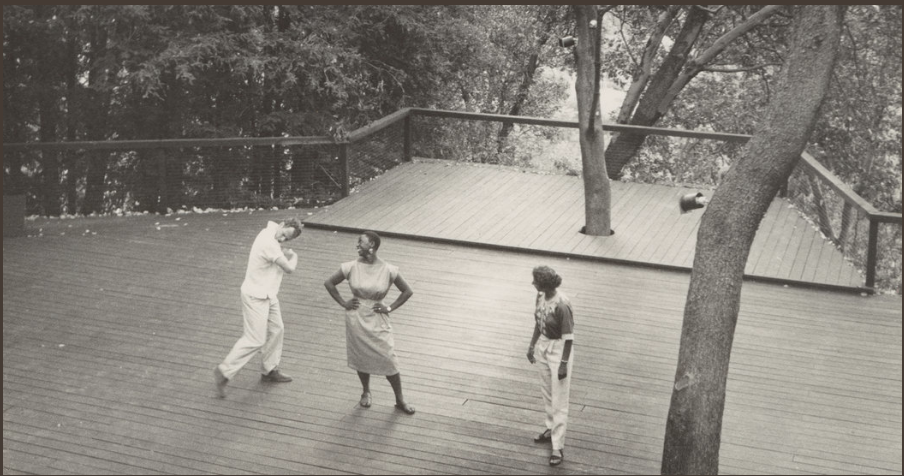

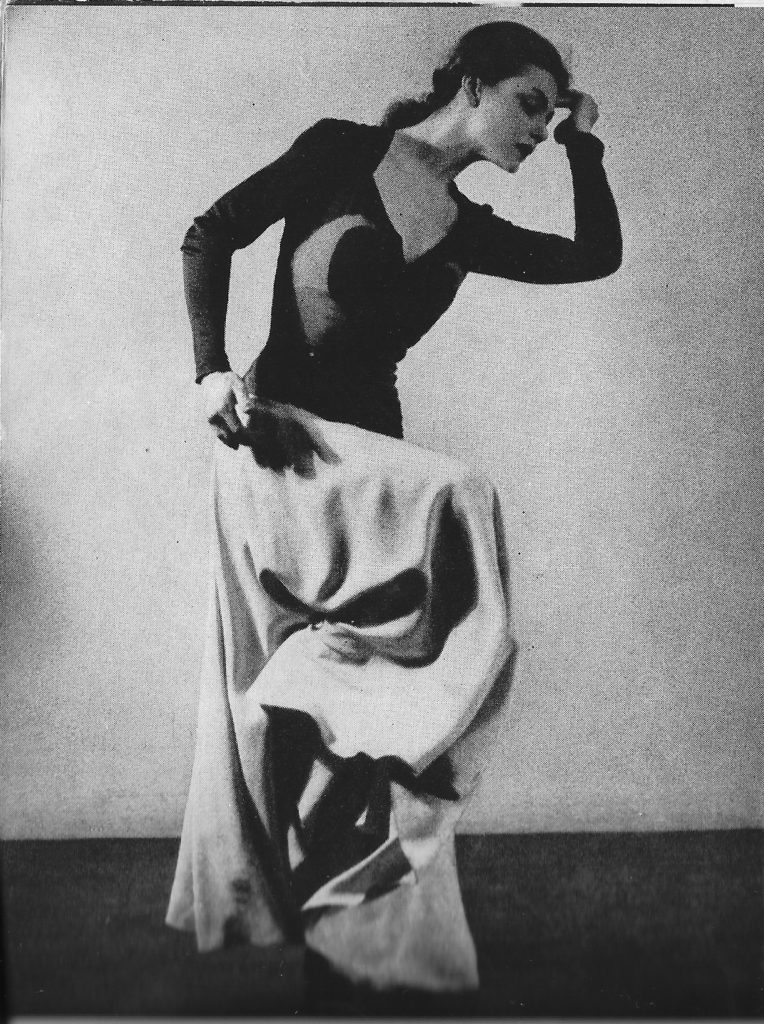

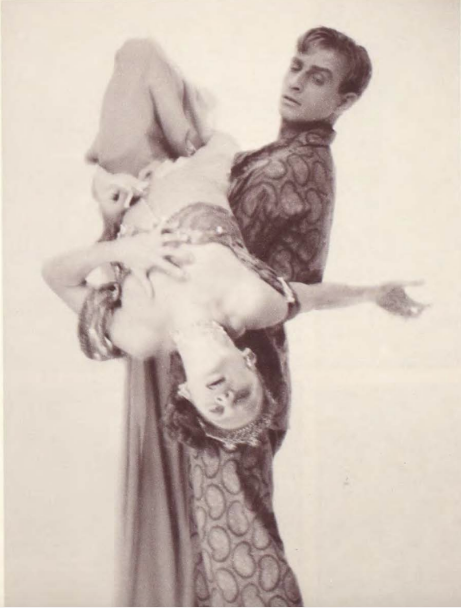

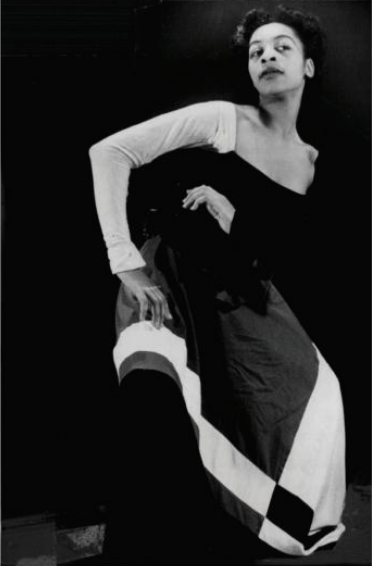

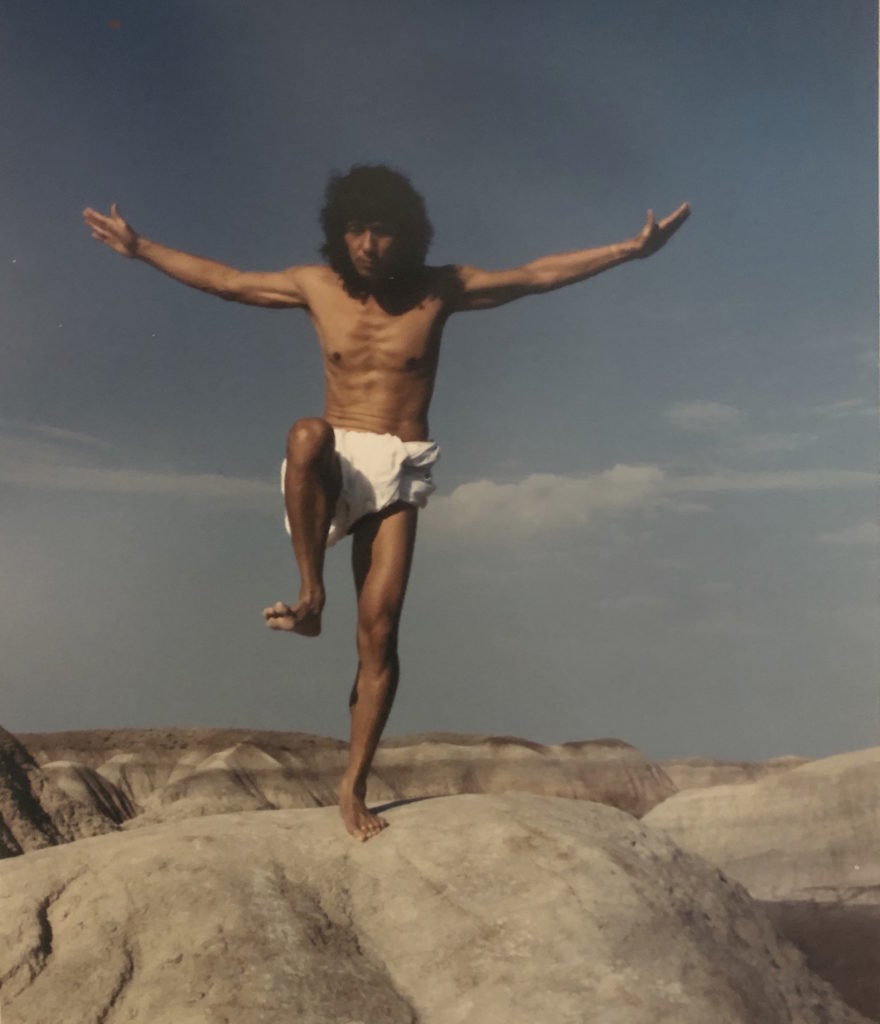

Jungle Wedding ph Soichi Sunami

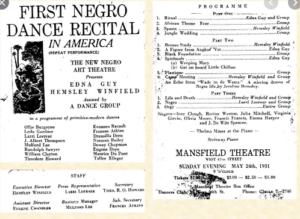

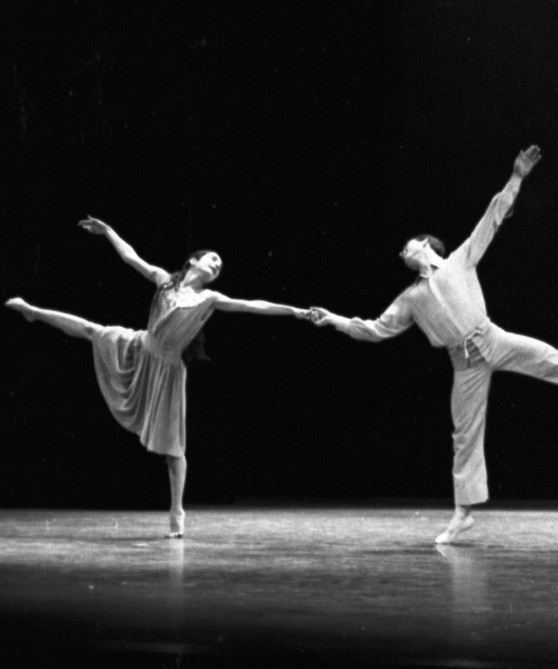

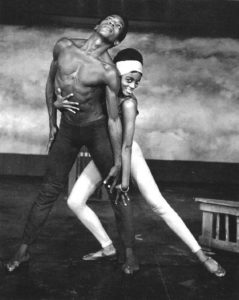

With this new/old name, the company gave the “First Negro Dance Recital in America,” presented by Winfield and Edna Guy, who had studied with Ruth St. Denis for six years. The venue was the “Theatre in the Clouds” on the fiftieth floor of the Chanin Building in midtown. Subtitled “a programme of primitive-modern dances,” it included eighteen dancers, eight singers, and a pianist. Winfield contributed most of the thirteen works, including Ritual, Bronze Study (which had been described by Mary Watkins of the New York Herald Tribune as mere reveling in his fine physique), Black Foundation, Plastique, Camp Meeting (a scene from Wade in de Water), and Life and Death. As a guest artist, Guy performed Ruth St. Denis’ A Figure from Angkor-Wat and her own Spirituals.

With this new/old name, the company gave the “First Negro Dance Recital in America,” presented by Winfield and Edna Guy, who had studied with Ruth St. Denis for six years. The venue was the “Theatre in the Clouds” on the fiftieth floor of the Chanin Building in midtown. Subtitled “a programme of primitive-modern dances,” it included eighteen dancers, eight singers, and a pianist. Winfield contributed most of the thirteen works, including Ritual, Bronze Study (which had been described by Mary Watkins of the New York Herald Tribune as mere reveling in his fine physique), Black Foundation, Plastique, Camp Meeting (a scene from Wade in de Water), and Life and Death. As a guest artist, Guy performed Ruth St. Denis’ A Figure from Angkor-Wat and her own Spirituals.

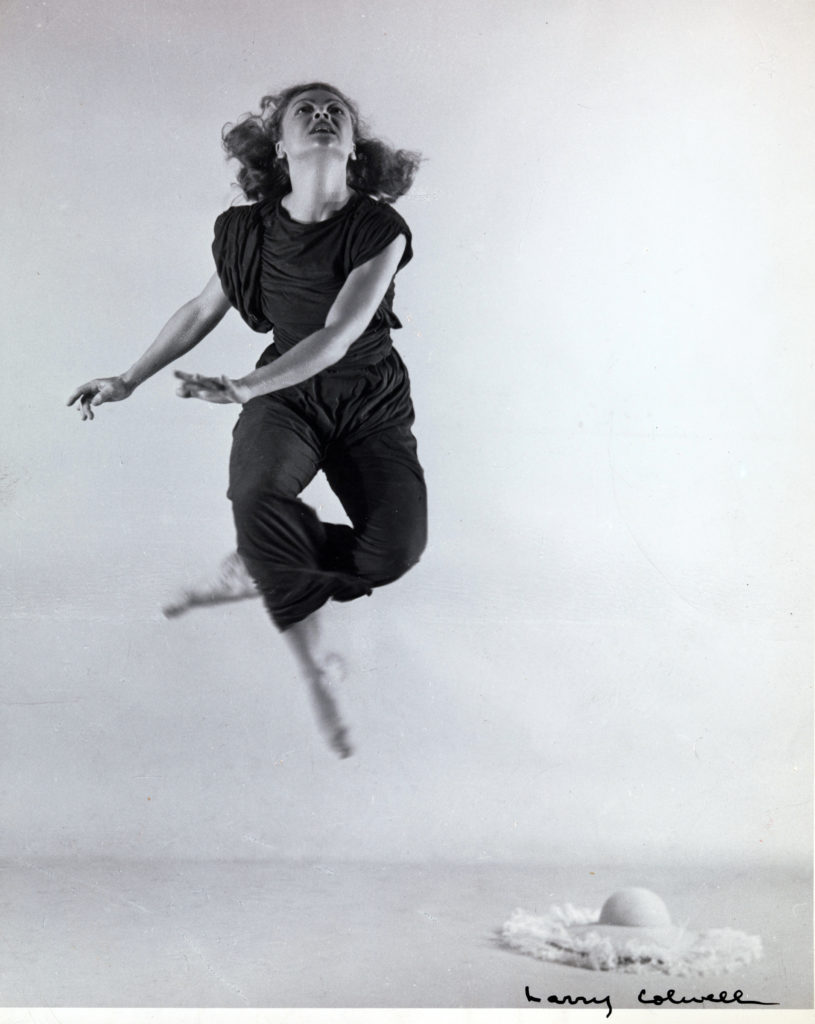

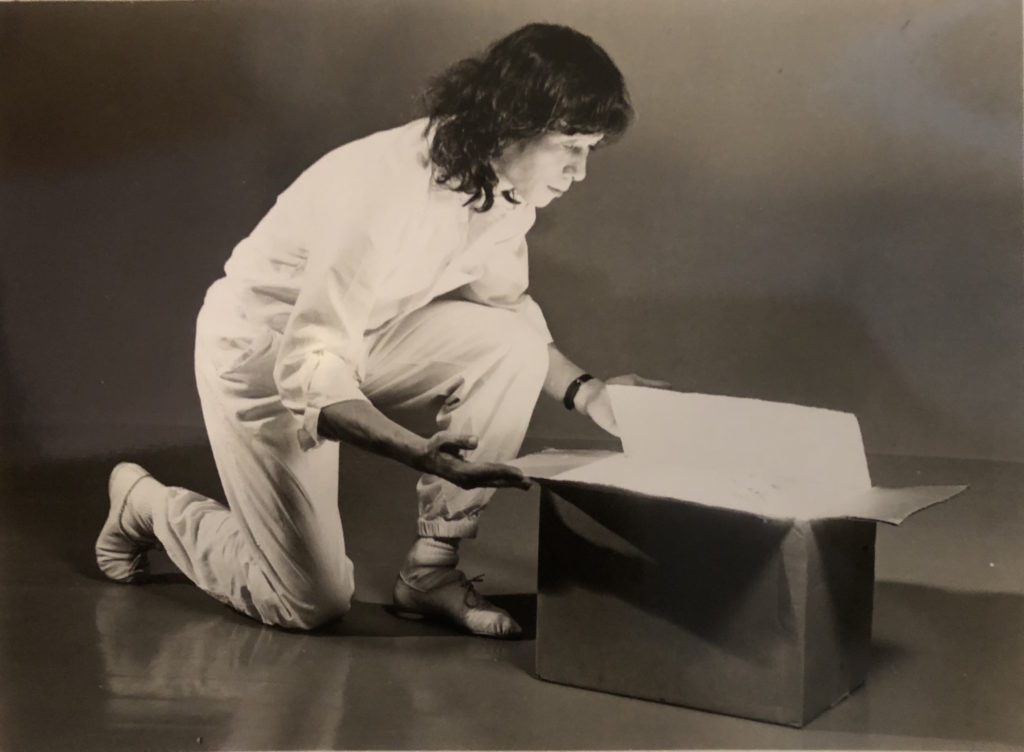

Edna Guy in A Figure in Angkor-Wat by Ruth St. Denis, 1931

John Martin, the dance critic of The New York Times, proclaimed the program “the outstanding novelty of the dance season” (Nash, Free to dance; also Neal, 157). Dance writer Charles Isaacson lauded the company, predicting that “within the next five years the biggest development in dancing will come from the Negro.” He was more favorable toward the group’s dancing than the choreography. However, he wrote,

Such numbers as Camp Meeting, Life and Death, [and] Ritual may be looked upon as the beginnings of great and important choreographic creations—compositions which in time will rival the production of the Russian Ballet. Praise is due Edna Guy and Hemsley Winfield (Neal, 72-73).

The program was repeated at the slightly larger Mansfield Theatre in midtown in May.

Other Dance Performances

Although a whole evening of the New Negro Art Theatre Dance Group was rare, the company gave their energies to many benefits. Some examples: 1) the “Monster Benefit” for the Dancers’ Club relief and scholarship fund, directed by the unlikely trifecta of Michel Fokine, Ruth St. Denis, and Ned Wayburn which took place at the Mecca Temple (now New York City Center). Among those on a crowded program were Bill “Bojangles” Robinson, Charles Weidman, and Fred Astaire. 2) the Pullman Porters Brotherhood at the Lafayette Theatre at midnight in a cast that included Duke Ellington, Ethel Water, and Small’s Paradise Revue. 3) A benefit for the cruelly framed Scottsboro Boys that involved W. C. Handy, the star tappers Buck and Bubbles, and others.

Other venues included the Harlem Academy (Neal 113), Roerich Hall, Henry Street Settlement Playhouse, the Abyssinian Baptist Church (Neal 142), City College, Dunbar Palace (during which Winfield premiered a dance cheekily titled The Sensation of Marihuana [sic]), and outdoors at the Lido Terrace with three Black composers: Duke Ellington, Alston Burleigh, and William Grant Still (Perpener 52).

As part of the Let Freedom Ring spectacular at the Roxy in Feb 1932, headlined by Will Rogers, Winfield and thirty dancers joined with the Hall Johnson singers. The story took the audience from slave ships to the cotton fields to Lincoln the Great Emancipator. The “Hot Cotton” number involved the Roxyettes, precursor to the Radio City Rockettes. One critic commented that “Hall Johnson’s chorus of two hundred and Hemsley Winfield and his New Negro Art Theatre dance group are drawing many curtain calls at the Roxy” (Neal 82-83).

Although Winfield was welcomed as a performer and teacher in many places, he came up against American racism quite close to home. When he tried to open a school in the nearby Dunwoodie section of Yonkers, people protested with sticks and stones and signs saying things like “We want white tenants in our white community.” The residents sent letters to the Yonkers Statesman. One letter read, “The colored people weren’t wanted in Dunwoodie. They’ll be lynched if they try to stay here” (Neal 14). Headlines reported, “Dunwoodie Is Aroused Over Near Race Riot, Threats Make Colored Folk Abandon Plans for Little Theatre: Mob in Demonstration Before Old Church” (Neal, Forgotten Pioneer). Undaunted, Winfield set up a school in Harlem.

Artistic Growth

At a certain point, John Martin of The New York Times noted that Winfield had grown artistically. He wrote that Winfield managed to avoid two traps of Black dance artists of the period: producing stereotypes and imitating white choreographers (Perpener 46-47). (To which Joe Nash responded in a 1976 article, “How quickly we forget the lessons of history. Who did the copying, borrowing, and stealing of dance styles, patterns, and steps in the first place?” [Nash, Drums 8]) Martin admired Winfield’s integrity, saying that the dancer refused to associate himself “with the amusement business of Harlem, where the Negro with his proverbial good nature presents himself as what the white amusement seekers like to think he is” (Martin). Presumably he’s talking about venues like the Cotton Club, where entertainers like the joyful Nicholas Brothers and the sexy Earl “Snake Hips” Tucker—and even Duke Ellington and his “jungle music”—gave white audiences what they expected.

Like Martha Graham, whose company debuted in 1926, Winfield regarded dance as an art that deserved to be put on the concert stage. It’s a sad irony that he was devoted to the larger mission of the Harlem Renaissance to celebrate Black arts, but his particular discipline—dance—was not respected by Du Bois and others (Perron 35). As Perpener has pointed out, the low esteem that Harlem elites had for dance stemmed from their view of vernacular dance as lower class (Perpener 17).

Workers Dance League

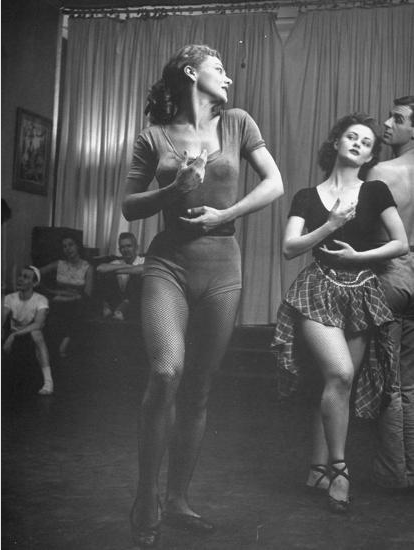

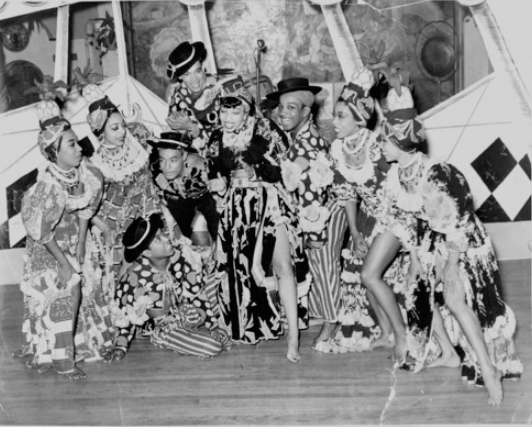

A poster showing Edith Segal’s Black and White with Add Bates in foreground.

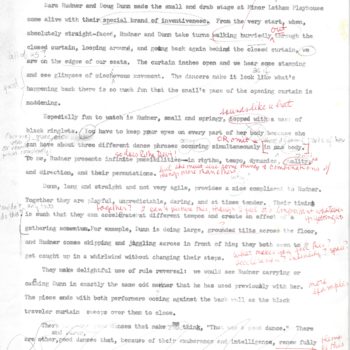

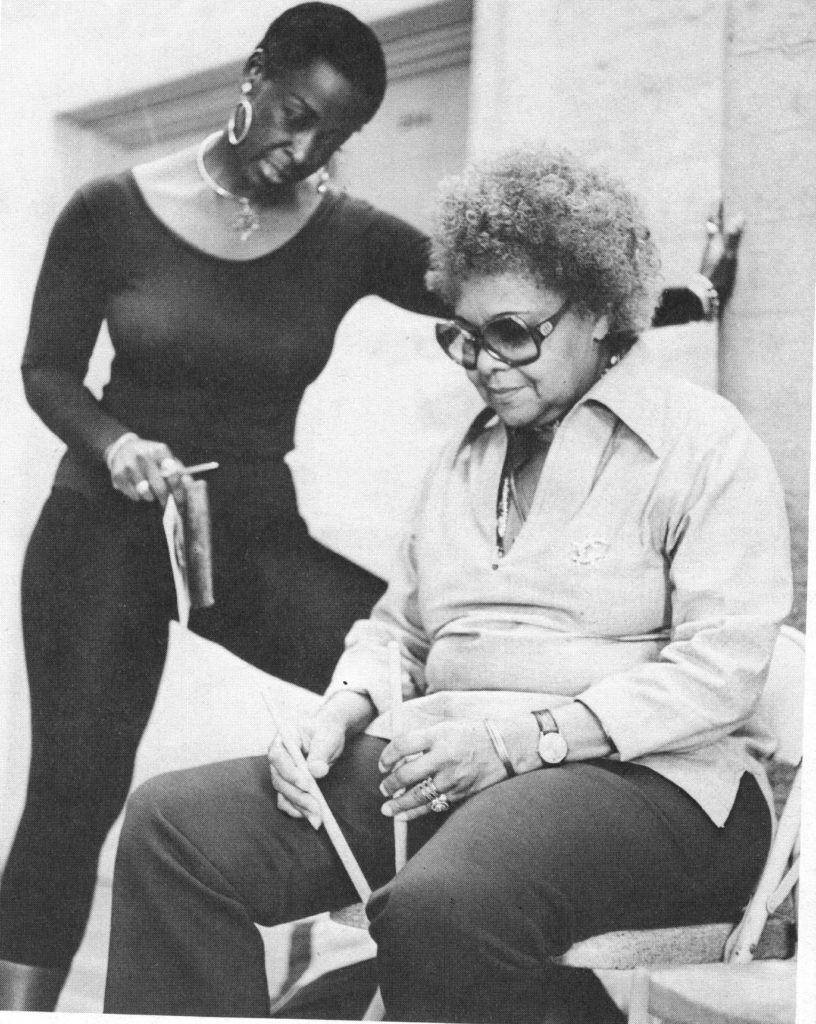

In Winfield’s last year, the Workers Dance League, a consortium of leftist dance groups, held a series of forums at the 135th Street YWCA. The first one addressed this question: What Direction Shall the Negro Dance Take?” (Some versions say the question was “What Shall the Negro Dance About?”) It was co-led by Augusta Savage, well known Negro sculptress (who had supported Edna Guy’s work in the past), and Winfield (Neal 143).

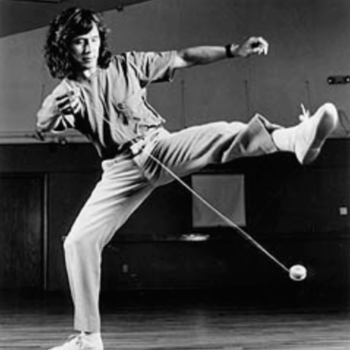

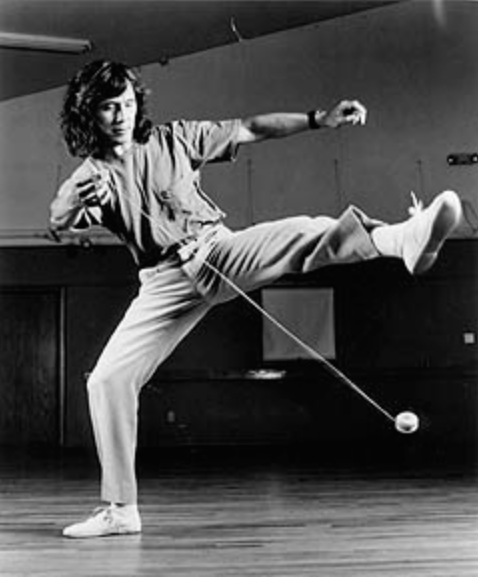

The performance component comprised Winfield’s Red Lacquer and Jade and Edith Segal’s Black and White (1930). The first was reviewed as showing “a fine feeling for the music” as well as “imagination and fantasy, emotional lucidity and restraint” (Manning 57). Segal’s piece was a short agitprop duet for a white man and a Black man alternating swings of the hammer, suggesting that laborers of different races could work together.

During the discussion Winfield was low-key. His opening statement was measured:

The Negro has primitive African material that he should never lose. The Negro has his work songs of the South which he alone can express. It’s hard for me to say what the Negro should dance about. What has anyone to dance about? (Manning 58).

The dancer Add Bates, who had just performed Segal’s Black and White, spoke up from the audience: “A young Negro should dance about the things that are vital to him. There should be a militant direction there. There should be some fights.” One young woman added,

We have come to a newer type of dance, a dance that has social significance. Since we recognize the Negro as an exploited race, our dance should express the strivings of the new Negro. It should express our struggle for social, economic, and political equality, and our part in the struggle against war (Perpener 53).

Winfield listened to these comments, which seem to be harbingers of the Civil Rights movement and Black Lives Matter. But, from his summarizing statement—“I have heard things tonight that have made me think” (Manning 58)—we don’t know if he was swayed at all. My guess is that, having felt scolded (or scalded) by Du Bois’ written rules for Negro theater, Winfield did not want to subject himself to a new set of rules about Negro dance.

The Emperor Jones

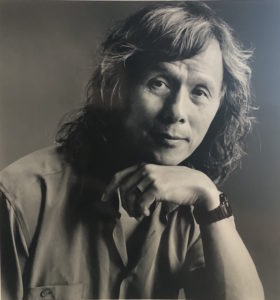

Opportunities to perform kept coming to Winfield and his company. In January 1933, when he was cast as the Congo Witch Doctor in Louis Gruenberg’s operatic version of Eugene O’Neill’s The Emperor Jones, Winfield became the first African American to be contracted by the Metropolitan Opera. (It’s often said that the singer Marian Anderson was the first, in 1955. But actually, Winfield was, and the second was ballet dancer Janet Collins in 1951 [Cheatham, 172].)

(Note: Another landmark set by Winfield’s appearance at the Metropolitan Opera had to do with dance rather than race: Not since 1910, when Anna Pavlova and Mikhail Mordkin took the audience by storm with their first performance in America, did the Met host a dance company.)

As the Witch Doctor, he was the fourth lead in Emperor Jones. The famous baritone Lawrence Tibbett, playing the Emperor in blackface, had insisted that Winfield be chosen for the role and that his company play the natives. He met with resistance from the management, which, according to Joe Nash, had planned to put the Met singer and dancers in blackface, as they had done for Dance in the Place Congo in 1918. Tibbett threatened to quit unless the Winfield group appeared. The Met finally agreed but retaliated by dropping the dancers’ names—and even the name of the group—from the Playbill.

Like Katherine Dunham a few years later, Winfield had traveled to the Caribbean to study African diasporic dance forms there, which probably helped him choreograph his role of the Witch Doctor as well as the ensemble numbers. Mary Watkins’ review in the New York Herald Tribune attests to how transporting his performance was, even within the stereotype of the “primitive” native:

Mr. Winfield was… after Mr. Tibbett, the hero of the occasion . . . his sinister and frantic caperings as the Witch Doctor made even the most sluggish, opera-infected blood run cold. His company, members of the New Negro Art Theatre Group, approached its work in much the same vein, renewing with no apparent difficulty, the racial traces of savagery long sublimated in the elegant sophistication of Harlem . . . The scene as the curtain fell was a vortex of horrid gayety [sic], a bloody revel for which Death beat the intoxicating rhythms. For one miraculous moment Broadway receded from consciousness, leaving the audience stranded in the midst of a too realistic nightmare. That this has been accomplished at the Metropolitan Opera it is a privilege to record, a matter of fair congratulations to whomever was inspired to seek out Mr. Winfield and to make his achievement possible (Neal 118-19).

Bruce Gulden of Dance Culture was equally excited by Winfield. He did not review the production favorably but wrote that,

Hemsley Winfield as the witch-doctor gave a thrilling exhibition of savage dancing. His body swayed, turned and twisted, and with jerky staccato yet rhythmic movements, he swung his arms about full of expression and emotion. His dance became more frantic and violent as the music increased in intensity. He seemed to cast a spell upon the audience. His scene was by far the most magnetic and pulsating scene in the entire work (Neal 119).

Screen grab of Winfield as Witch Doctor, 1933

Winfield’s last performance of Emperor Jones was March 18, 1933. He was scheduled to appear when the opera was reprised in January 1934, but by then he was too sick with pneumonia. His mother said it was brought on by overwork and over worry about his company’s future. From a hospital bed, he designated his dancer Leonard Barros to replace him as the Witch Doctor and to oversee the company. He died January 15, 1934. One hundred and fifty people attended the memorial service that was held three weeks later in his last Harlem dance studio. In tribute, Augusta Savage created a mixed-media art work.

Legacy

For an artist whose life was cut short at 26, Winfield made a remarkable contribution. It’s enticing/agonizing to imagine what he could have accomplished if he’d lived longer. He might have sustained a Black dance company well before Katherine Dunham. He might have become a choreographer for musicals as did George Faison, Donald McKayle, and Geoffrey Holder. He might have choreographed enduring works. He might have expanded his vision of Blacks in dance.

John Martin, looking back, characterized the early Black pioneers as “full of energy and experimentation” and wrote that its leaders, specifically Hemsley Winfield and Edna Guy, were “fairly indomitable” (Martin 179).

Perpener has written,

The regularity with which critics had mentioned his leadership, discipline, dedication and blossoming artistry pointed toward a special promise, the promise of continued development of his individual aesthetic, even greater artistic output, and the codification of a dance technique that took into account the cultural roots of black artists (Perpener 54).

In her obituary, Watkins wrote that Winfield “was regarded in dancing circles as the initiator and chief exponent of Negro concert dancing in the Unites States” (Neal 159).

After his death, two of his dancers, Juanita Baker and Leonard Barros, reformed the group into the Modern Negro Dance Group. As Susan Manning points out, it was the only group to use both “Modern” and “Negro” in its title, thus combining two identities that were usually perceived as separate (Manning 64). The Modern Negro Dance Group shared a concert with the Workers Dance League at Brooklyn Academy of Music, reprising Life and Death, and then disbanded. Both Baker and Barros found work in the Negro Unit of the Federal Theatre Project, which gave work to artists during the Depression (Manning 65).

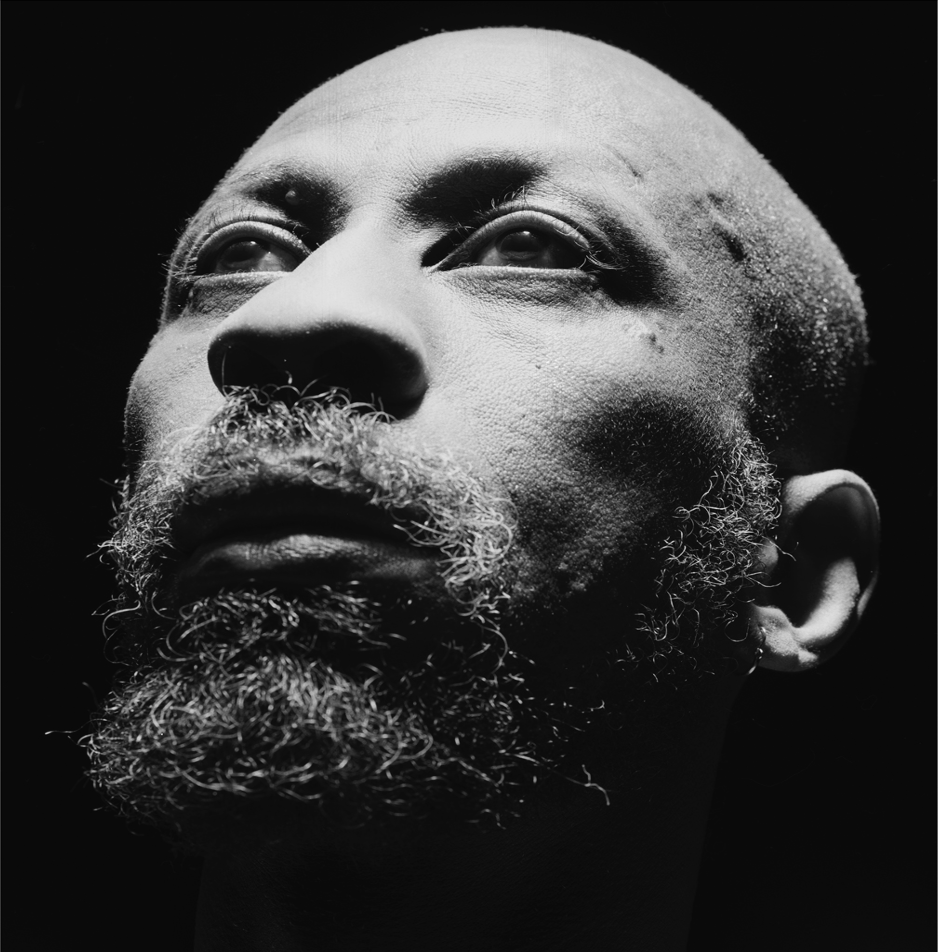

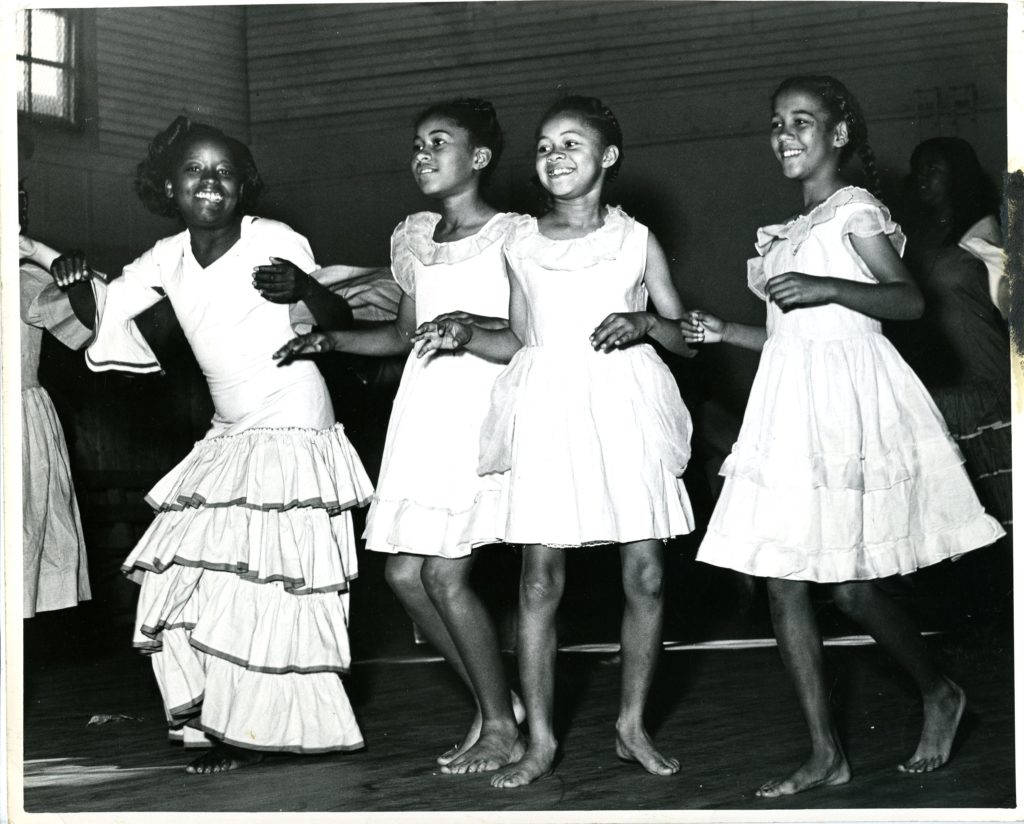

Archie Savage

Though his life was tragically short, Winfield planted seeds that continued to grow. Randolph Sawyer went on to dance with Asadata Dafora and in Billy Rose’s Carmen Jones on Broadway, working with the choreographer Eugene Loring (Perpener 72-73). Archie Savage became a leading dancer with Katherine Dunham and had his own group for a while. Olga (Ollie) Burgoyne, a vaudeville performer who met Winfield during Lulu Belle, continued dancing freelance, including in Run Little Chillun, which Doris Humphrey choreographed. Edna Guy continued organizing; it was she who brought Dunham to New York to perform in the “Negro Dance Evening” in 1937.

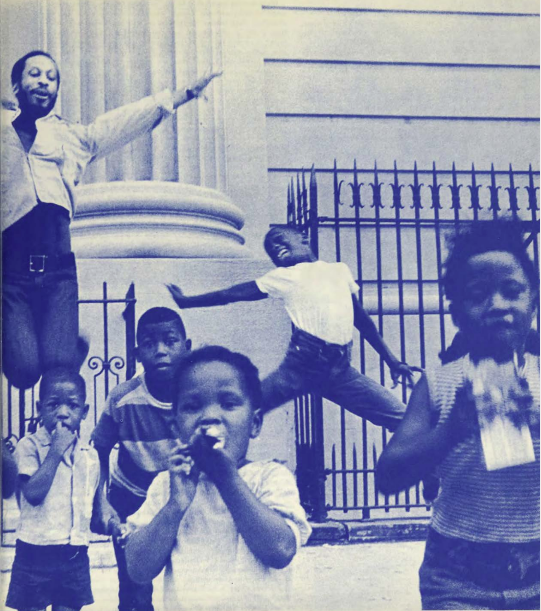

Richard Nugent was also cast in Run Little Chillun (and was delighted when José Limón replaced Doris Humphrey as his coach); he later danced with Dafora (Wirth in Nugent 31) and Wilson Williams (Wirth 33). Decades later, as co-chair of Harlem Cultural Council, Nugent was instrumental in organizing the DanceMobile, the flatbed truck that brought dance artists like Eleo Pomare and Syvilla Fort to inner city neighborhoods.

Toward the end of his life, Winfield told his dancers, “We’re building a foundation that will make people take black dance seriously” (Nash, Drums 9, and Free to Dance).

Augusta Savage’s mixed media painting

¶¶¶

This essay is dedicated to Joe Nash, an Unsung Hero himself. I wish we could keep talking about all of this.

¶¶¶

Works Cited

Books

Duberman, Martin Bauml. Paul Robeson. London: Pan Books, 1989.

Manning, Susan. Modern Dance, Negro Dance: Face in Motion. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2004.

Martin, John. John Martin’s Book of the Dance. New York: Tudor Publishing Company 1963, 1970.

Neal, Nelson. Hemsley Winfield: Pioneer of Modern Dance. Self-published, 2020.

Nugent, Richard Bruce. Gay Rebel of the Harlem Renaissance: Selections from the Work of Richard Bruce Nugent, Ed. and Intro by Thomas H. Wirth, Foreword by Henry Louis Gates. Durham: Duke University Press, 2002.

Perpener, John O, III. African-American Concert Dance : the Harlem Renaissance and Beyond. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2001.

Wilson, James F. Bulldaggers, Pansies, and Chocolate Babies: Performance, Race, and Sexuality in the Harlem Renaissance, Accessed as ebook Feb. 15, 2021.

Articles and Essays

Gauss, Rebecca G. “O’Neill, Gruenberg, and “The Emperor Jones.” The Eugene O’Neill Review, Vol. 18, No. 1/2 (Spring/Fall 1994), pp. 38–44.

McBreen, Ellen. “Biblical Gender Bending in Harlem: The Queer Performance of Nugent’s Salome.” Art Journal, Vol. 57, No. 3 (Autumn, 1998), pp. 22–28.

Nash, Joe. “Dancing Many Drums.” The Birmingham Times, National Scene Magazine Supplement, September–October, 1976, pp. 1–12.

Perron, Wendy. “Dance in the Harlem Renaissance: Sowing Seeds.” EmBODYing Liberation: The Black Body in American Dance, Dorothea Fischer-Hornung and Alison D. Goaler, eds. Forecaast, Vol. 4, 2001, pp. 23–39.

Poueymirou, Margaux. “The Race to Perform: Salome and the Wilde Harlem Renaissance.” Refiguring Oscar Wilde’s Salome, volume ed. Michael Y. Bennett, 2011. ProQuest Ebook Central, pp. 201–209, accessed Feb. 20, 2021.

Internet Sources

Hemsley Winfield: The Forgotten Pioneer of Modern Dance, by Nelson D. Neal, Ed.D.

Nash, Joe. “Pioneers in Negro Concert Dance: 1931–1937,” PBS Free to Dance, Historic Essays.

W. E. B. Du Bois Papers, Credo Collection, UMass), accessed Feb. 26, 2021.

Cass, “Harlem’s Drag Ball History,” Harlem World, accessed Feb. 27, 2021.

Unsung Heroes of Dance History 2

but was less than artistically fulfilling.

but was less than artistically fulfilling.

Dance We Do: A Poet Explores Black Dance

Dance We Do: A Poet Explores Black Dance Daniel Lewis: A Life in Choreography and the Art of Dance

Daniel Lewis: A Life in Choreography and the Art of Dance Final Bow for Yellowface: Dancing between Intention and Impact

Final Bow for Yellowface: Dancing between Intention and Impact Martha Graham’s Cold War: The Dance of American Diplomacy

Martha Graham’s Cold War: The Dance of American Diplomacy The Fascist Turn in the Dance of Serge Lifar: Interwar French Ballet and the German Occupation

The Fascist Turn in the Dance of Serge Lifar: Interwar French Ballet and the German Occupation

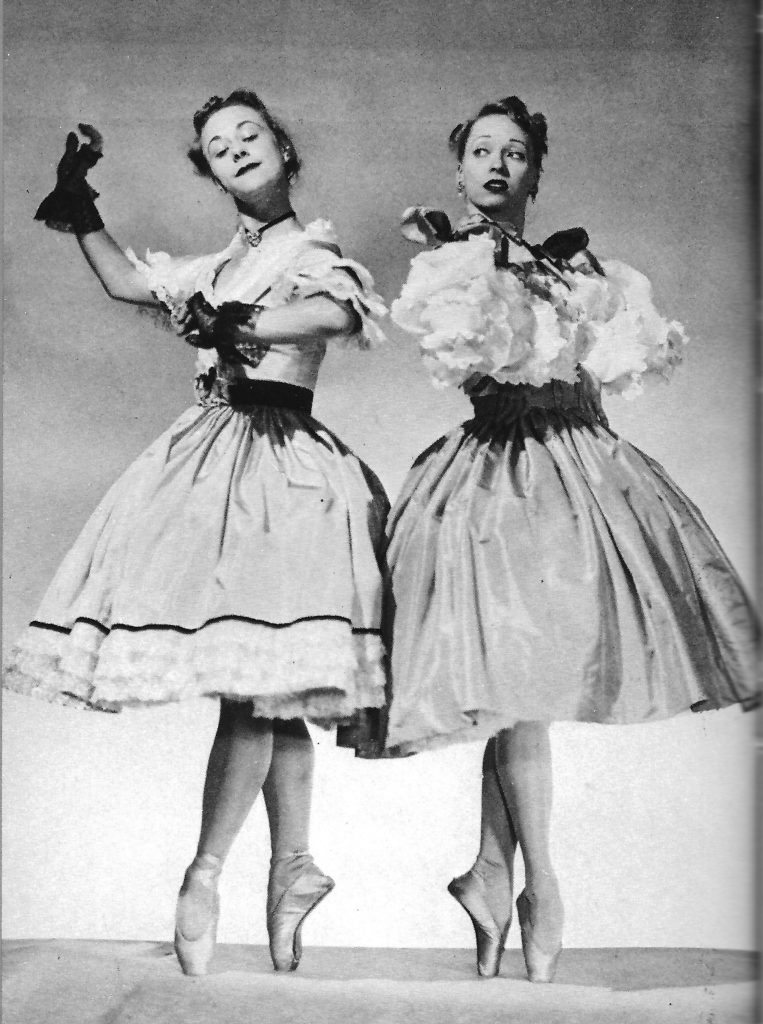

The Legat Legacy

The Legat Legacy Futures of Dance Studies

Futures of Dance Studies Ballet in the Cold War: A Soviet-American Exchange

Ballet in the Cold War: A Soviet-American Exchange Finding Balanchine’s Lost Ballets: Exploring the Early Choreography of a Master

Finding Balanchine’s Lost Ballets: Exploring the Early Choreography of a Master Catherine Littlefield: A Life in Dance

Catherine Littlefield: A Life in Dance Moving and Being Moved

Moving and Being Moved Fringe: Maria Benitez’s Flamenco Enchantment

Fringe: Maria Benitez’s Flamenco Enchantment Yvonne Rainer: Work 1961–1973

Yvonne Rainer: Work 1961–1973 Conversations with Meredith Monk

Conversations with Meredith Monk Howling Near Heaven: Twyla Tharp and the Reinvention of Modern Dance

Howling Near Heaven: Twyla Tharp and the Reinvention of Modern Dance

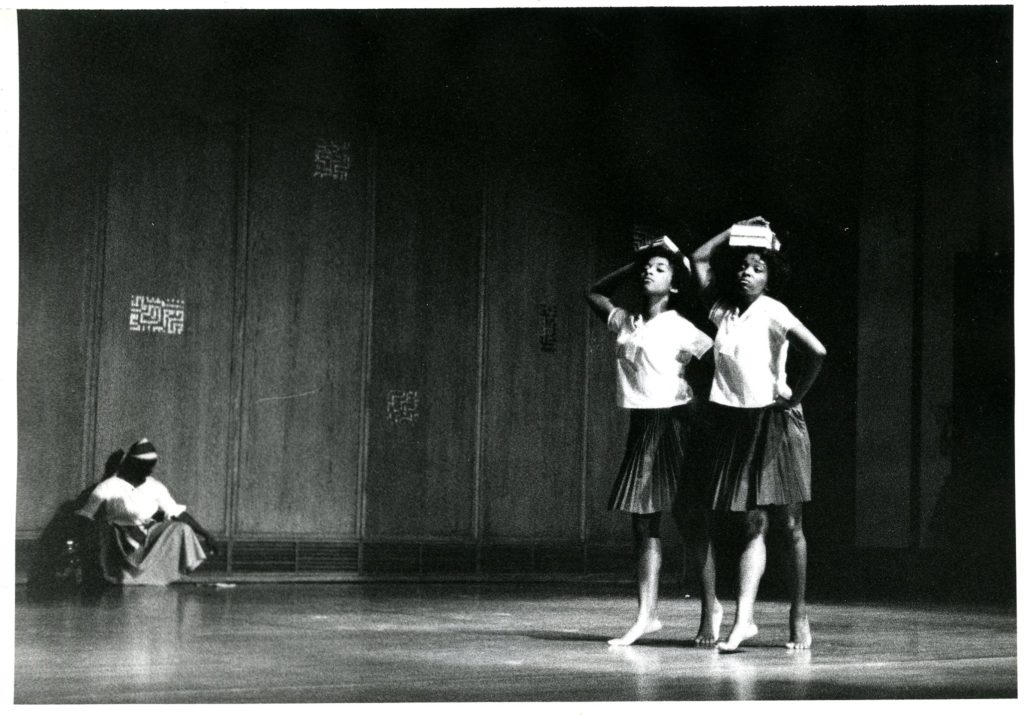

When she wasn’t on tour, Fort taught both Dunham technique and ballet there. Two of her students, Marion Cuyjet and Sydney King, asked her to guest teach at their studios in Philadelphia. She did teach in Philly during the 1947–48 school year but stopped in 1948, when she took on the responsibilities of dance director of the Dunham school. That same year, her mother died, making her the legal guardian of her 8-year-old brother, John Dill (together, at right). He joined her in Harlem and eventually became a drummer.

When she wasn’t on tour, Fort taught both Dunham technique and ballet there. Two of her students, Marion Cuyjet and Sydney King, asked her to guest teach at their studios in Philadelphia. She did teach in Philly during the 1947–48 school year but stopped in 1948, when she took on the responsibilities of dance director of the Dunham school. That same year, her mother died, making her the legal guardian of her 8-year-old brother, John Dill (together, at right). He joined her in Harlem and eventually became a drummer.

Pomare was a prolific choreographer whose work was too raw for prime time. As Anna Kisselgoff wrote in The New York Times, “Eleo Pomare’s dances always have a special gutsy quality.” His performances were hyper-realistic; indeed he was accused of being “too real.” Although he wasn’t invited to go on State Department–sponsored international tours like Alvin Ailey or to choreograph Broadway musicals like Donald McKayle, he kept making dances—118 in all. His courage and imagination were inspiring; his febrile physicality was startling. As dance historian Katrina Hazzard Donald says in the PBS special

Pomare was a prolific choreographer whose work was too raw for prime time. As Anna Kisselgoff wrote in The New York Times, “Eleo Pomare’s dances always have a special gutsy quality.” His performances were hyper-realistic; indeed he was accused of being “too real.” Although he wasn’t invited to go on State Department–sponsored international tours like Alvin Ailey or to choreograph Broadway musicals like Donald McKayle, he kept making dances—118 in all. His courage and imagination were inspiring; his febrile physicality was startling. As dance historian Katrina Hazzard Donald says in the PBS special