“Make something new out of something old.” That was an assignment that a drawing teacher at Bennington College (Sophia Healy) used to give. And the results were wonderfully layered.

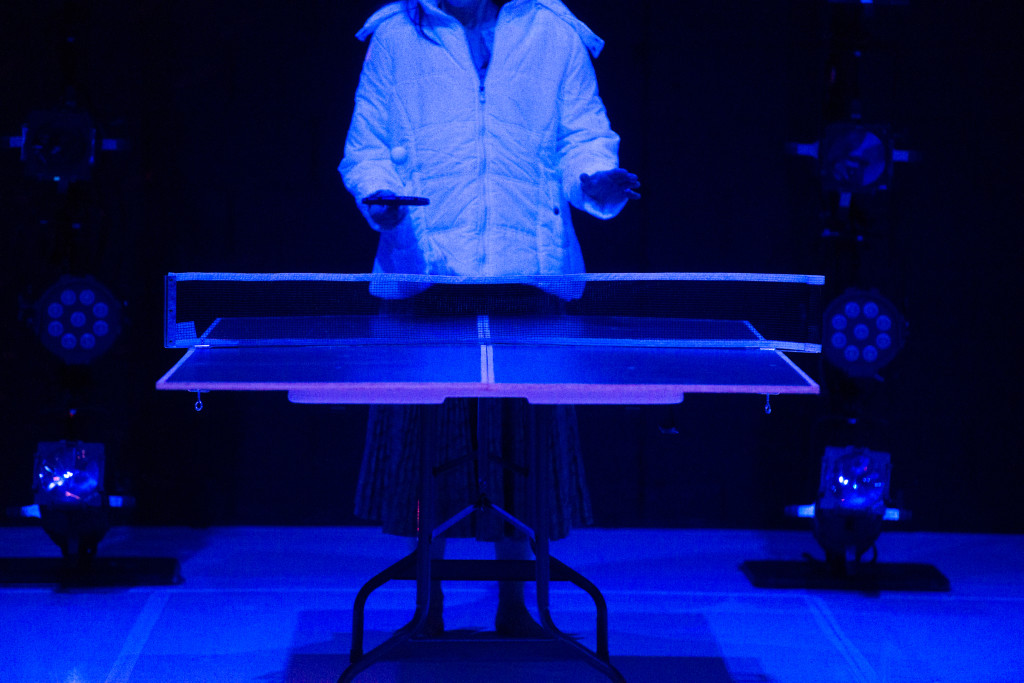

A stimulating example is ALLY, a multi-layered collaborative event that takes a few ideas of Anna Halprin’s and makes something new. Presented by the artist-friendly Fabric Workshop and Museum in Philadelphia, these ideas reverberate and expand through the minds and bodies of Stephen Petronio and Janine Antoni. The series takes place on four levels of the eight-storey Fabric Workshop.

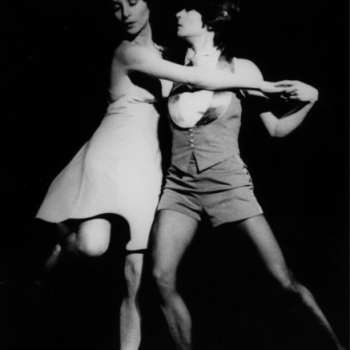

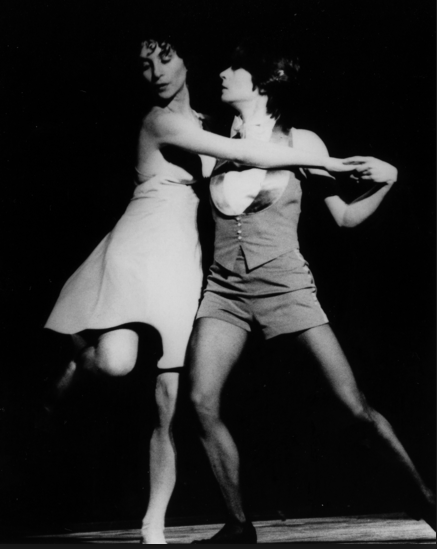

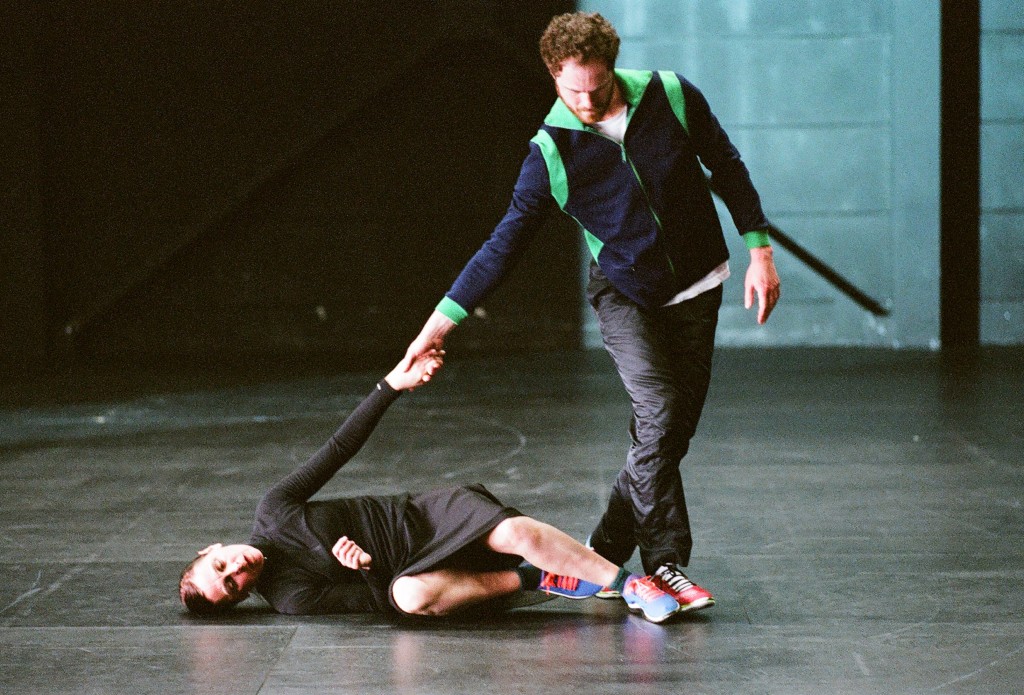

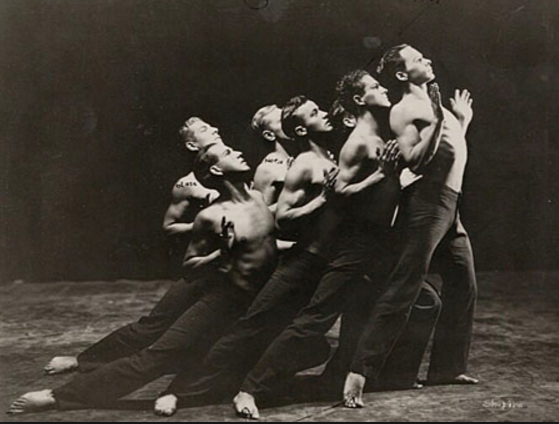

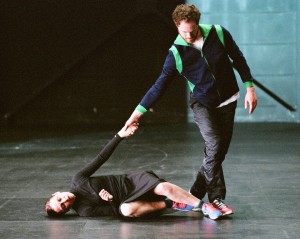

Petronio in Halprin’s The Courtesan and the Crone, at the Fabric Workshop and Museum, photo by Carlos Avendaño

Petronio has taken Halprin’s short, highly theatrical solo The Courtesan and the Crone (1999) and made it poignant for a different reason. Originally Halprin donned an elaborate mask and brocaded gown to suggest a beautiful young woman who gestures seductively in some previous century. When Halprin removed the mask, her aging face was revealed. Petronio, similarly bedecked, is fascinating to watch as he gets into the skin of a woman. To Baroque music, he beckons to the audience with white-gloved fingers and gives his torso a sensual torque worthy of Marilyn Monroe. When he takes the mask off, what is revealed is the “wrong” gender rather than the “wrong” age.

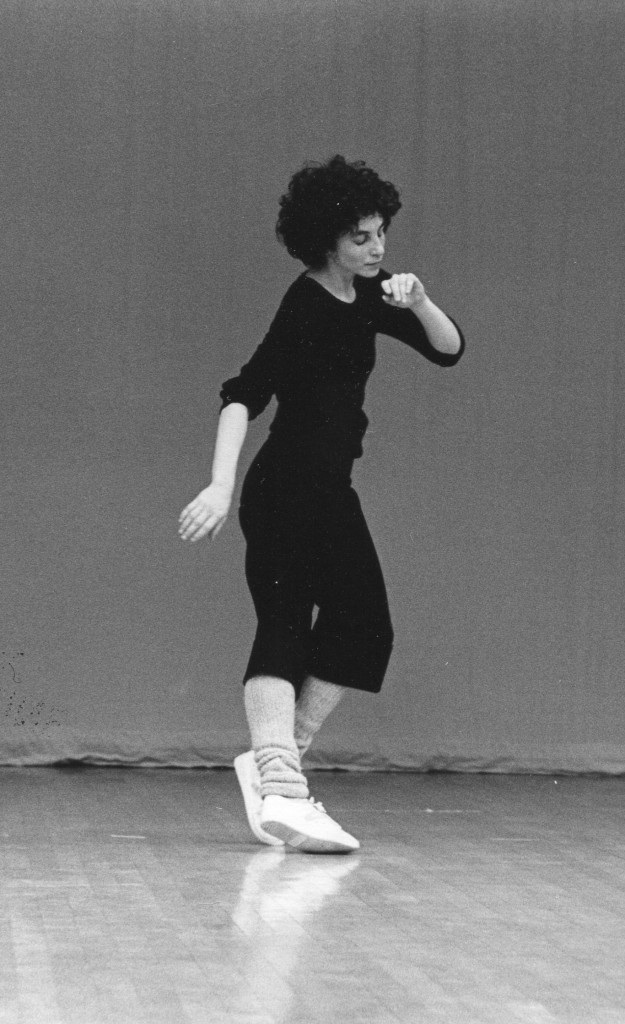

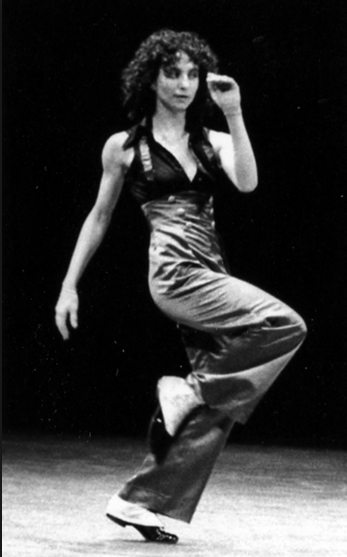

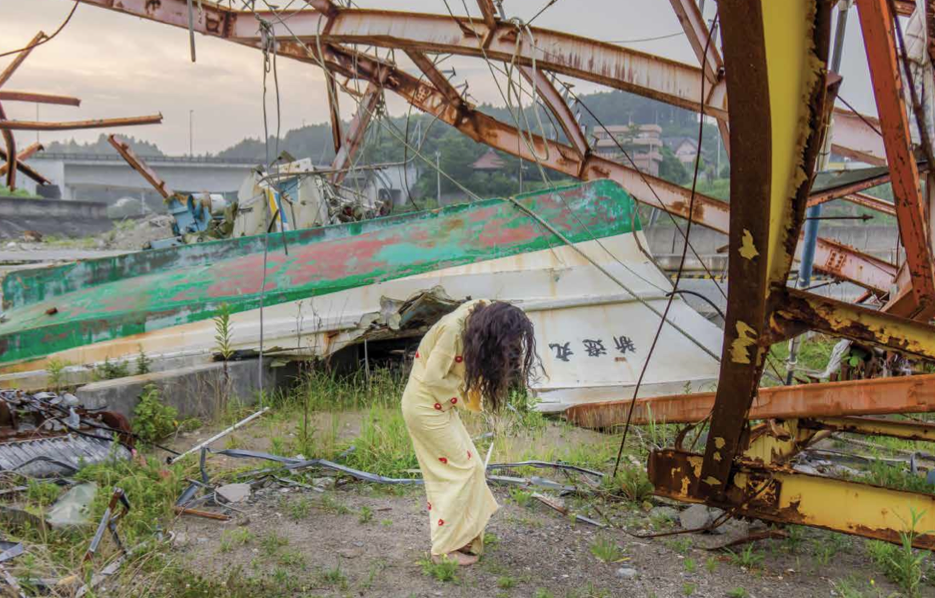

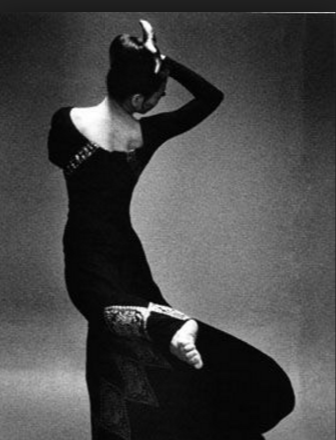

Antoni is not a dancer, but, like Halprin, she finds ways that her body can nestle into an environment. For her long solo on the 8th floor, inspired by Halprin’s “Paper Dance” from her landmark work Parades and Changes (1965-67), she crumples, pleats, and tears a roll of butcher paper, then fits her nude body into the sculpture formed by the variously ruptured paper in instinctive, almost animal ways.

Janine Antoni in collaboration with Anna Halprin, Paper Dance, 2013.

Photographed by Pak Han at the Halprin Dance Deck. Courtesy of the artists and

The Fabric Workshop and Museum, Philadelphia.

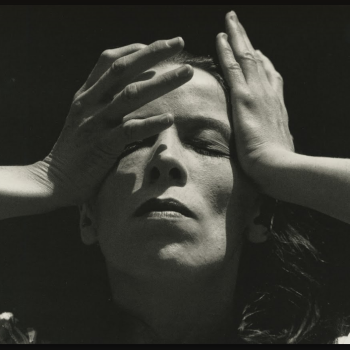

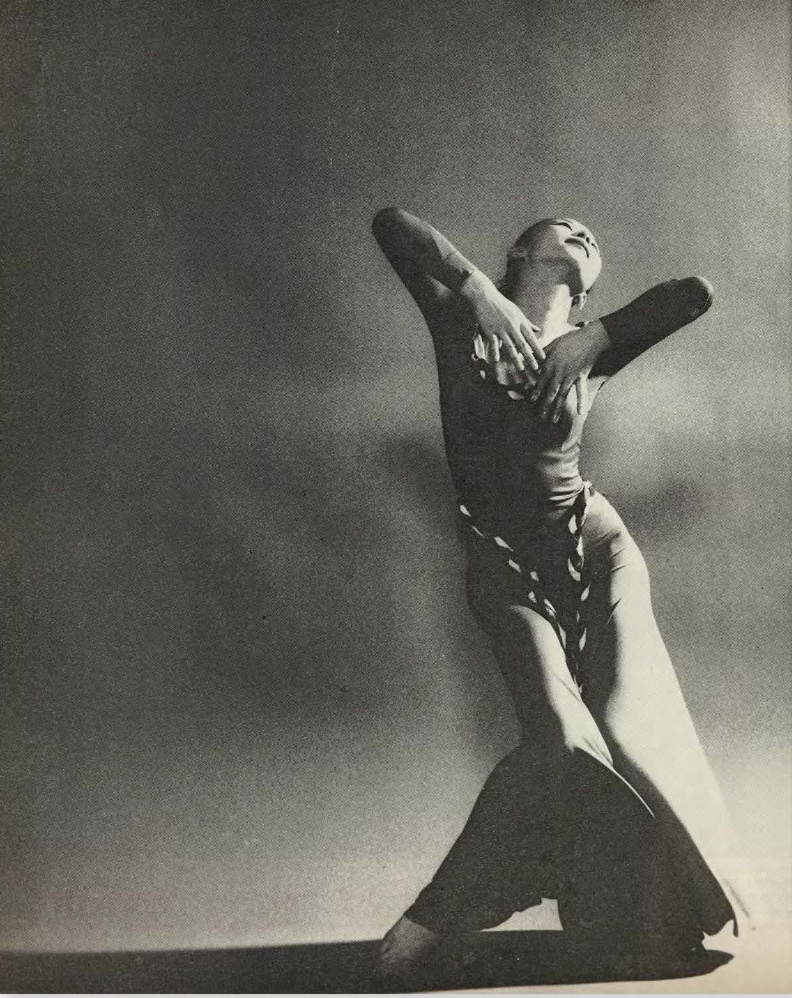

Rope is a true collaboration, instigated by Halprin’s wish to see the two younger artists in relation to each other. One of the softly brilliant things about Rope is that, to begin and end the piece, we watch Halprin’s face in a close up video taken on her famous outdoor deck in Marin County. In the video, she is reacting to Petroni and Antoni improvising according to her score for the rope dance.

Close-up of Anna Halprin as she watched a rehearsal of Rope, on dance deck

Since Halprin is 95 and not traveling much these days, it is a lovely way to have her with us. In the middle part of the dance Petronio gives control of the rope over to us, the people of the audience. This aligns with Halprin’s idea that there is no audience—we are all participants—as well as her faith in the ordinary, non-trained moving body involved in a task.

There are many criss-crossing ideas, disciplines, and genres to be gleaned from these performances and installation. ALLY continues until July 31, 2016. Click here for (a rather complex schedule of) performances times and tickets.

Around the Country what to see Leave a comment

• Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker and Boris Charmatz’s Partita 2 at Sadler’s Wells in London. Postmodern in the best sense: dance that creates structure and relationship from nothing but movement and squeaky sneakers. Energizing.

• Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker and Boris Charmatz’s Partita 2 at Sadler’s Wells in London. Postmodern in the best sense: dance that creates structure and relationship from nothing but movement and squeaky sneakers. Energizing.

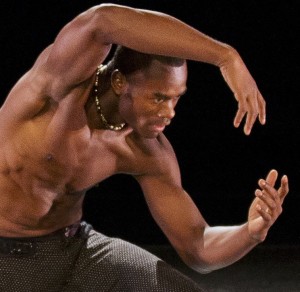

• Jamar Roberts in the Ailey company, magnificent in works by Robert Battle, Paul Taylor and Ron Brown and more. (photo of Roberts in Aszure Barton’s LIFT, by Paul Kolnik)

• Jamar Roberts in the Ailey company, magnificent in works by Robert Battle, Paul Taylor and Ron Brown and more. (photo of Roberts in Aszure Barton’s LIFT, by Paul Kolnik)

This Very Moment: teaching thinking dancing

This Very Moment: teaching thinking dancing Rhythm Field: The Dance of Molissa Fenley

Rhythm Field: The Dance of Molissa Fenley What the Eye Hears: A History of Tap Dancing

What the Eye Hears: A History of Tap Dancing Like a Bomb Going Off: Leonid Yakobson and Ballet as Resistance in Soviet Russia

Like a Bomb Going Off: Leonid Yakobson and Ballet as Resistance in Soviet Russia Alla Osipenko: Beauty and Resistance in Soviet Ballet

Alla Osipenko: Beauty and Resistance in Soviet Ballet Saving Radio City Music Hall: A Dancer’s True Story

Saving Radio City Music Hall: A Dancer’s True Story Lois Greenfield: Moving Still

Lois Greenfield: Moving Still Rupert Can Dance

Rupert Can Dance Changing the Conversation: The 17 Principles of Conflict Resolution

Changing the Conversation: The 17 Principles of Conflict Resolution