How could an evening devoted to grief be so uplifting? That was true of “Precarious: Guest Solos 1,” a collection of invited solos at Danspace Project on the Lower East Side. But it was also true of the entire month-long Platform 2016: A Body in Places, which included performances, workshops, photograph exhibits, talks and other wanderings from February 17 to March 23.

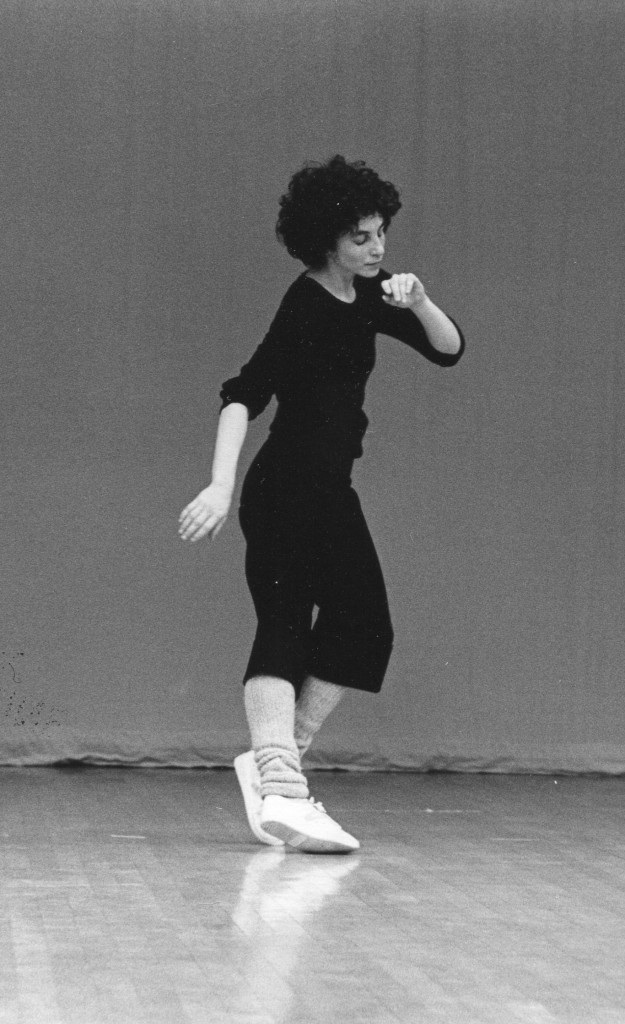

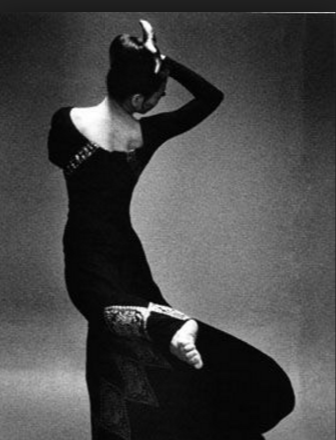

The answer is Eiko Otake, recently redefined as a solo dance artist. When you’re in the presence of her dancing, her aura fills time and space. You lose track of what century or country you’re in. She seems to transform the very air she occupies. You tap into a whole world of grief that, like a beautiful poem, makes you want to be near it.

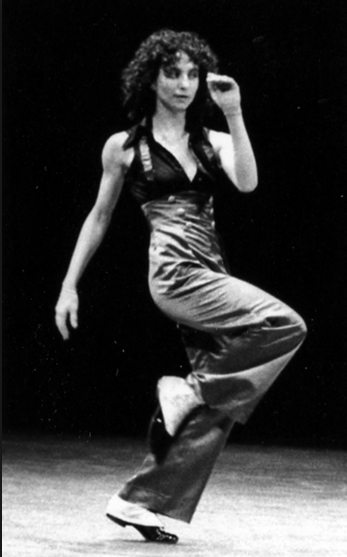

Eiko at local shop, photo by Ian Douglas

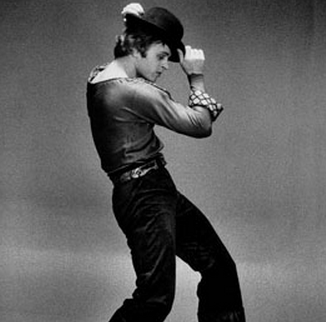

As a duo, Eiko and Koma could change the way you looked at the world. When you watched them inch along with their archetypal slowness, whether in a theater, a pool of water, or a museum, you might get the eerie feeling that a Japanese painting from a previous century was coming to life. Maybe you felt you were witnessing a primordial world that has no beginning or end.

During the Platform, Eiko’s stature grew from large to huge. It’s not only that Eiko herself expanded as an artist, but that her ideas and presence radiated like moonbeams, connecting to the luminous darkness in other artists and issues. It’s like the long and deep connection she had with Koma imploded, then exploded into a scintillas flying in different directions.

The Platform provided an Eiko-a-day infusion of spirit somewhere on the Lower East Side. I attended 3 of the 25 or so events and participated in one “Bearing Witness” talk session. Eiko brought her dancing, like a breeze of sorrow, into different sites. She might lurk in the shadows and then appear on the balcony, threatening to drop her kimono over the edge; she might whip her carefully collected reeds against a wall. Just when you thought she would fade away and die, she erupted with a burst of anger, rage, or subhuman moaning as though suddenly remembering all her children were dead. She included audience members by offering a stalk, or beckoning us to follow her.

A new element since her barefoot days with Koma was a pair of wooden sandals. She clomped around in them, teetered, and almost fell out of them. You were sure she would twist an ankle. (She didn’t, but she did sprain a wrist the first week and performed the rest of the Platform with a bandaged hand.)

A typical beginning of one of her solos: Nestled close to the ground, she doesn’t budge for minutes. We see the swirling designs of her kimono move before we see her shift underneath. Her fingers and the soles of her feet look so fragile. Brian Seibert in his New York Times review of March 2, described the startling sight:

“At 9 a.m. on Monday, if you had peeked through the storefront window of Dashwood Books on Bond Street in Manhattan, you would have seen a body on the floor, sleeping or possibly dead. Slowly, out of tattered Japanese robes emerged whitened feet, gnarled and aged and terribly exposed.”

Seibert also wrote about the powerful effect of looking into her eyes:

“When her gaze briefly meets yours, it’s still unclear whether she sees you, but the possibility is enough to be harrowing. It’s a look you might have seen on a homeless person or a refugee, a piercing look that reminds you of your sins and makes you count your blessings.”

I too received that piercing look and was transfixed by it. I had actually seen her just before the show started, when she happily confessed that she was nervous. Minutes later, she became a completely different creature.

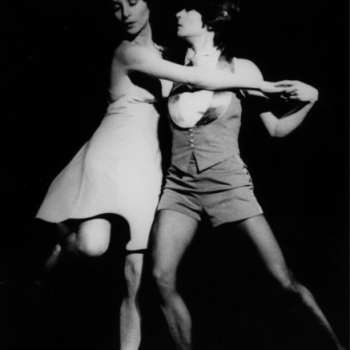

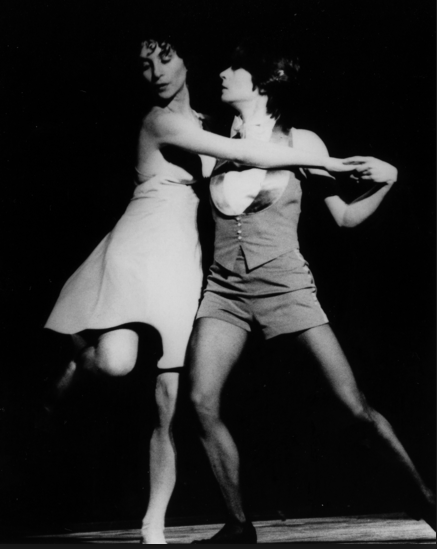

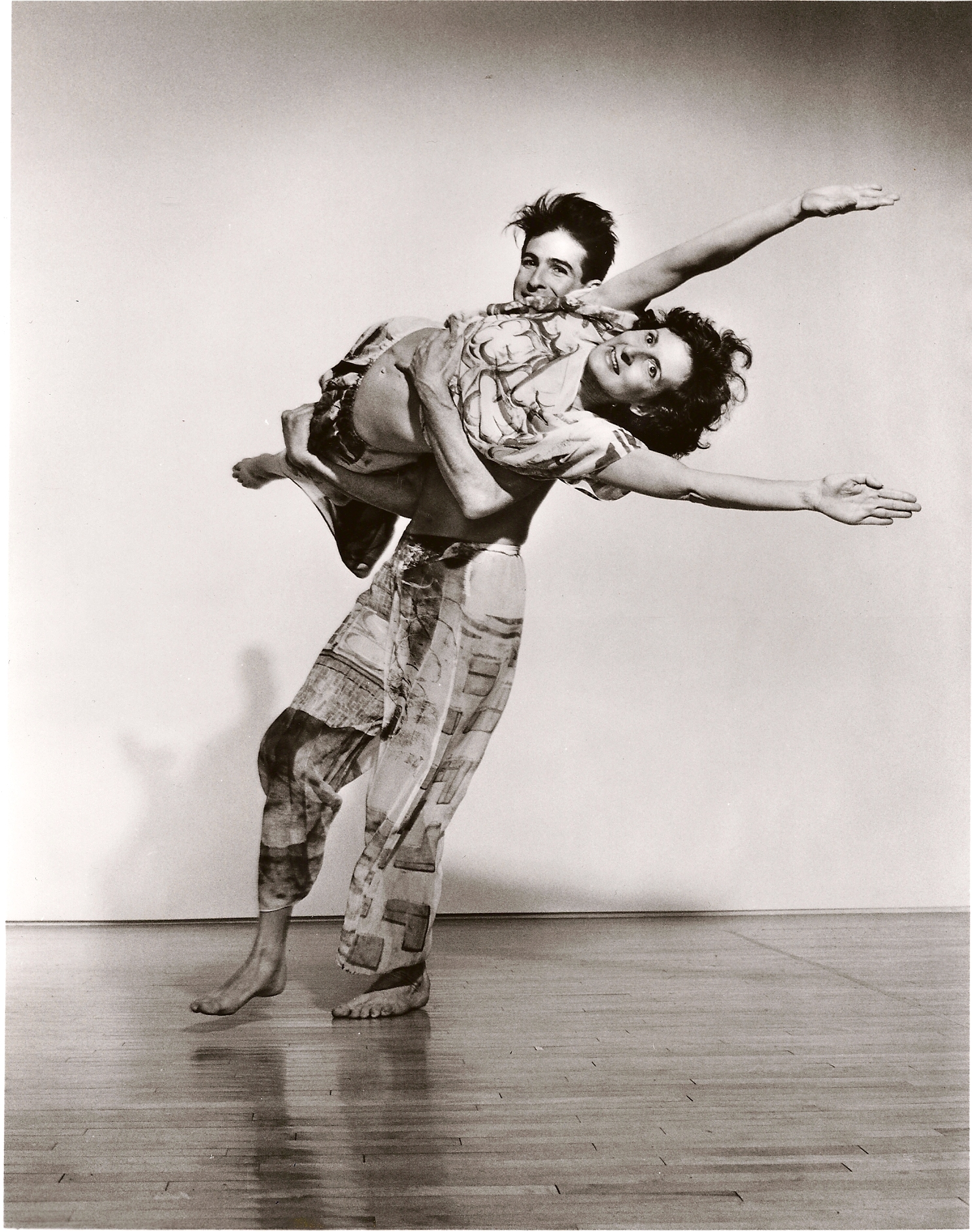

Talking Duets with David Brick and John Kelly (curator Lydia Bell is at left), photo by Ian Douglas

But in some ways her work partnering other dancers was even more startling. As Siobhan Burke pointed out in The New York Times, during “Talking Duets I” many got a whiff of Eiko’s sense of humor for the first time. Instead of an ancient goddess in whiteface, she became a downtown denizen with delightful witticisms of body and voice. She danced with Emmanuelle Huynh, leading off a series of duets. To give some shape to these chance encounters, Danspace director Judy Hussie-Taylor posed questions from a table. I remember David Brick carrying John Kelly and, in answer to a question, Kelly was singing a lovely Irish ditty.

Eiko’s playful timing and natural warmth seemed to be contagious. I’d never seen Bebe Miller be so funny.

But to return to the grief evening, or rather the invited solos inspired by grief (Judy Hussie-Taylor had given each artist a quote from Judith Butler), the diversity of interpretations was part of what was uplifting. Koma chose to perform his solo, “Dancing with My Painting and Lion,” outside in the cold, lurching from dirt ground to stone lion statue while tango music played. Beth Gill, inspired by Eiko and Koma’s Husk (1987), oozed along the carpeted risers in the Sanctuary during almost the whole three hours. And Donna Uchizono quietly interviewed audience members in the Parish Hall about a remembered loved one before improvising with that information. After being deep in conversation with audience member Ralph Lemon, she immersed herself in a remarkably evocative improvisation.

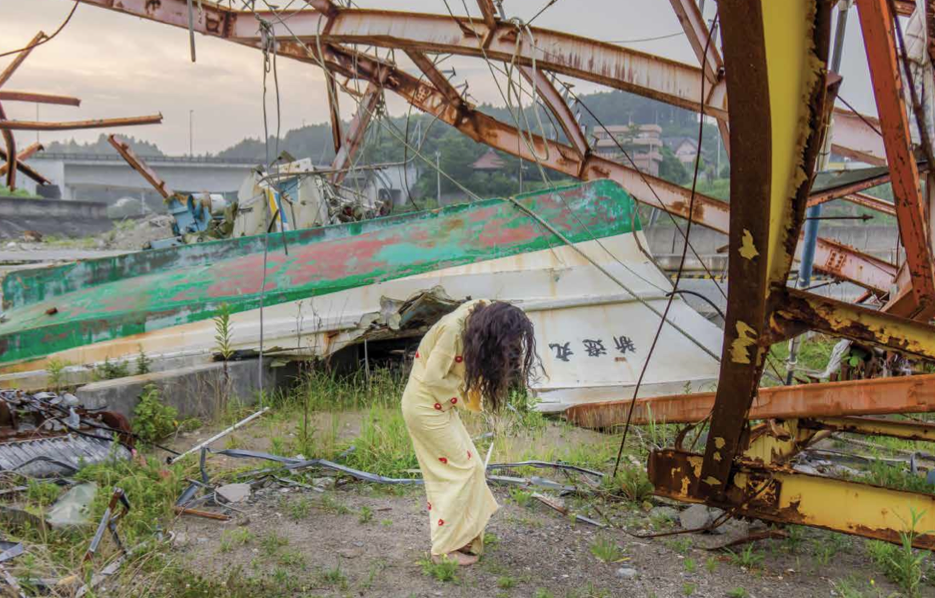

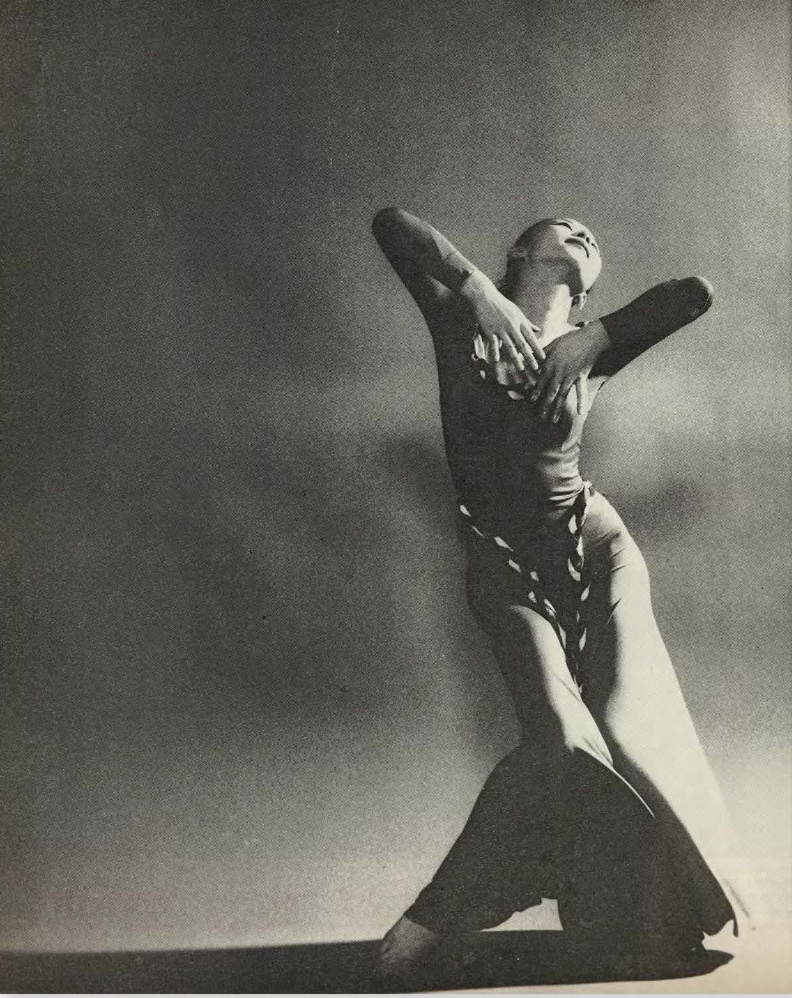

Part of the inspiration for the Platform can be traced back to Eiko’s harrowing project with photographer William Johnston, A Body Fukushima (2014). Together they traveled to irradiated areas in and around the damaged Fukushima Daiichi nuclear reactors. These images of Eiko, even more “terribly exposed,” yet fitting in harmoniously to those godforsaken landscapes, are uncannily beautiful.

Near Fukushima, 2014, photo by William Johnston

After one of the solos in the neighborhood, I was overwhelmed. I visited Eiko “backstage.” I said to her, “Your body carries all the sadness of the world.” Her immediate response was, “Don’t we all?”

I participated in a “Bearing Witness” event as a commemoration of five years since the nuclear meltdown at Fukushima. Prompted by the idea of the artist as wanderer, scholars and performers spoke about various ramifications of Eiko’s work. Yoshiko Chuma, fresh from a work period with dancers in Palestine, talked about the dangers facing people there. Both Yoshiko and Eiko are fearless wanderers who enter dangerous territories without a second thought.

Eiko expressed her worry that the Body in Fukushima images were merely beautiful and did not prompt action. But I expressed my thought that the photos go beyond beauty and reach into the observer’s feelings. They create a connection with the unfortunate people from Fukushima who are living in exile, and by extension, with all refugees.

This Platform provided a long, lingering look at a monumental artist, one who is willing to embody the sorrows of life on this earth. With Eiko’s generous spirit, the Platform shed light on other artists’ experience as well. Kudos to Danspace, to Hussie-Taylor, and to Platform curator Lydia Bell for choosing and shaping this deeply moving and thought-provoking experience.

Although the Platform ended in March, you can still see some of Eiko’s solos in this video collage.

Featured Leave a comment

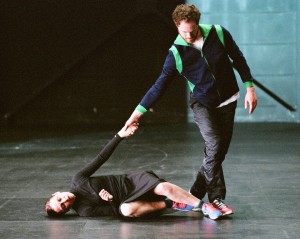

• Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker and Boris Charmatz’s Partita 2 at Sadler’s Wells in London. Postmodern in the best sense: dance that creates structure and relationship from nothing but movement and squeaky sneakers. Energizing.

• Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker and Boris Charmatz’s Partita 2 at Sadler’s Wells in London. Postmodern in the best sense: dance that creates structure and relationship from nothing but movement and squeaky sneakers. Energizing.

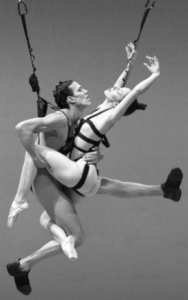

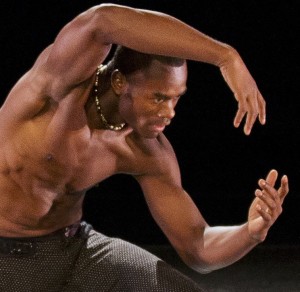

• Jamar Roberts in the Ailey company, magnificent in works by Robert Battle, Paul Taylor and Ron Brown and more. (photo of Roberts in Aszure Barton’s LIFT, by Paul Kolnik)

• Jamar Roberts in the Ailey company, magnificent in works by Robert Battle, Paul Taylor and Ron Brown and more. (photo of Roberts in Aszure Barton’s LIFT, by Paul Kolnik)

This Very Moment: teaching thinking dancing

This Very Moment: teaching thinking dancing Rhythm Field: The Dance of Molissa Fenley

Rhythm Field: The Dance of Molissa Fenley What the Eye Hears: A History of Tap Dancing

What the Eye Hears: A History of Tap Dancing Like a Bomb Going Off: Leonid Yakobson and Ballet as Resistance in Soviet Russia

Like a Bomb Going Off: Leonid Yakobson and Ballet as Resistance in Soviet Russia Alla Osipenko: Beauty and Resistance in Soviet Ballet

Alla Osipenko: Beauty and Resistance in Soviet Ballet Saving Radio City Music Hall: A Dancer’s True Story

Saving Radio City Music Hall: A Dancer’s True Story Lois Greenfield: Moving Still

Lois Greenfield: Moving Still Rupert Can Dance

Rupert Can Dance Changing the Conversation: The 17 Principles of Conflict Resolution

Changing the Conversation: The 17 Principles of Conflict Resolution