[I wrote this article for the August, 2000 issue of Dance Magazine. Reprinted with permission.]

[I wrote this article for the August, 2000 issue of Dance Magazine. Reprinted with permission.]

All Roads lead to Katherine Dunham. Well, not all. But sometimes it seems to be so. Jazz dance, “fusion” and the search for our cultural heritage all have their antecedents in Dunham’s work as a dancer, choreographer and anthropologist. She was the first American dancer to present indigenous forms on a concert stage, the first to sustain a black dance company, the first black person to choreograph for the Metropolitan Opera. She created and performed in works for stage, clubs and Hollywood films; she started a school and a technique that continue to flourish; she fought unstintingly for racial justice. She could have had her own TV show called “Dance Roots.”

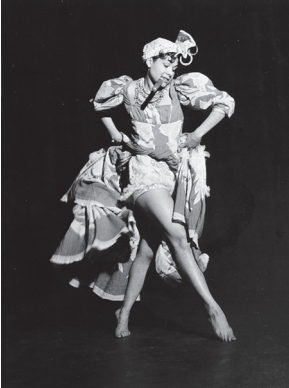

Rara Tonga (1940)

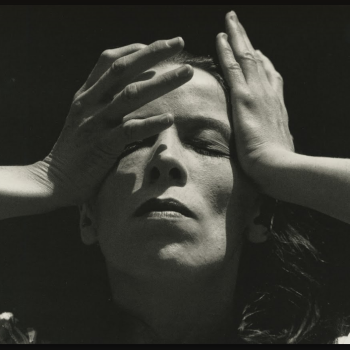

Dunham, 91, lives in Manhattan, where she is working on an autobiography, Minefield, while undergoing physical therapy for her surgically replaced knees. Surrounded by former dancers, friends and a bright-eyed two-and-a-half-year-old goddaughter, she regales them with stories, songs, and warm-hearted joking.

The young Katherine Dunham studied ballet with Mark Turbyfill of the Chicago Opera and the Russian dancer Ludmilla Speranzeva. When she was only 21, with Turbyfill’s help, she formed the short-lived Ballet Nègre. Soon after, she started the Katherine Dunham Dance Company, which was based in Chicago during the early years. Carmencita Romero, who danced with Dunham from 1933 to 1941, said the company performed a mix of cultures even then: “We did Russian folk dances with full skirts, Spanish dances influenced by La Argentina and Carmen Amaya, and plantation dances like Bre’r Rabbit an’ de Tah Baby.”

In 1935, Dunham, under the aegis of a Rosenwald fellowship, traveled to the Caribbean to research African-based dances. She returned in 1936, having passed rigorous initiation rites to become a mambo—a vaudun priestess. She soon choreographed pieces that reflect Haitian movements, for instance, the Yanvalou, in which the spine undulates like the snake god, Damballa. But more than that, she absorbed the idea of dance as religious ritual. She has said, “In vaudun we sacrifice to the gods, but the top sacrifice is dance.” Shango (1945), which depicts such a sacrifice, hypnotized audiences during the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater’s celebration of Dunham, The Magic of Katherine Dunham, in 1987.

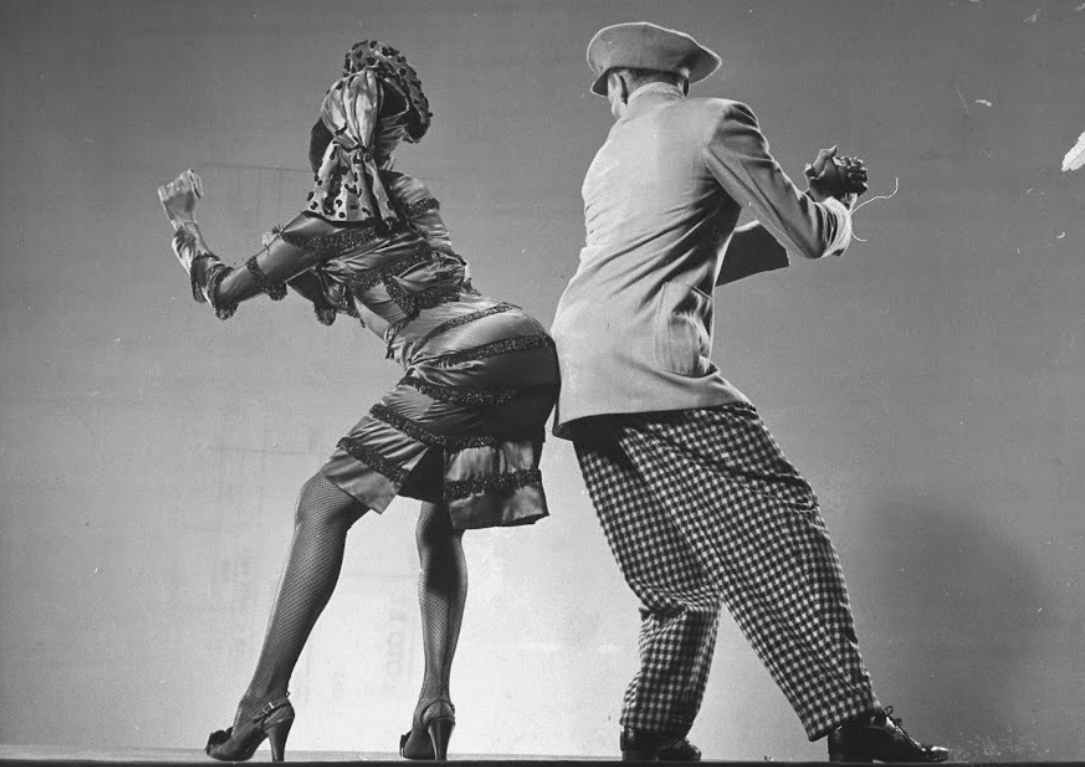

Barrelhouse Blues (1940)

Dunham also focused on American dance forms: “I was running around getting all these exotic things from the Caribbean and Africa when the real development lay in Harlem and black Americans,” she says. “So I developed more things in jazz.” Her revue, “Le Jazz Hot” (1940), included vernacular forms like the shimmy, black bottom, shorty george and the cakewalk. That same year, Dunham worked with George Balanchine on the choreography of the Broadway musical Cabin in the Sky. She recalls, “He took an Arab song and taught it to me for a belly dance.” About their collaboration, she confesses, “He was a help, but I was pretty adamant about what I wanted to do. We had a wonderful time together.”

One of the few works of hers that was filmed was Carnival of Rhythm (1941). In this clip she is seen dancing with Archie Savage, who had danced with Hemsley Winfield.

In 1943, the international impresario Sol Hurok presented Dunham’s company in “Tropical Revue” at the Martin Beck Theater on Broadway, adding Dixieland jazz musicians to boost its commercial appeal. The show became a hit, enjoying a six-week run, unusual for such a revue. Dunham was a glamorous performer, and it is rumored that Hurok had insured her legs for a million dollars. In an interview with biographer Ruth Beckford, Dunham demurred, saying the amount was a mere quarter million.

Dunham opened a school in Manhattan in 1945. Dana McBroom-Manno, who was a student there and later danced with Dunham, describes the Dunham technique as modern with an African base. “You use the floor as earth, the pelvis as center, holding torso and legs together. You work for fluidity, moving like a goddess, undulations like water, like the ocean. High leaps for the men. You elongate the muscles, creating a hidden strength. We use both parallel and turned out, so it’s easy to go from Dunham into any other technique. The isolations of the hips, ribs, shoulders that you see in all jazz classes were brought to us from the Caribbean by Miss Dunham. Also, she [talked about] Indian chakra points (in yoga, points of physical or spiritual energy in the body).” Romero, who has taught dance history at The Ailey School, emphasizes the spirit. “In Africa, all dance is based on animals, plants, the elements of the universe. The Dunham technique gives you a feeling of release and exhilaration by letting the body go.”

The Dunham school, Eartha Kitt in foreground, James Dean at right

Syvilla Fort correcting James Dean

The Dunham school, in the Times Square area, thrived for ten years. Its thirty teachers offered classes in ballet, modern (José Limón was one of the modern teachers), “primitive,” acting, martial arts and more. Among its students were James Dean, Arthur Mitchell, Butterfly McQueen and Doris Duke. Donald Saddler, recently reminiscing, said Marlon Brando would come and play drums. Sometimes jazz bassist and composer Charles Mingus would come with a group of his musicians and play for classes.

Out of the school came a student group, directed by the legendary Syvilla Fort, that included Julie Belafonte, Walter Nicks, and Peter Gennaro. This group performed at schools and benefits. Belafonte—who met her husband, Harry, though one of these performances—recalls: “We were taught the rhythms of the movements with drums and with song in other languages; for instance, Portuguese and Haitian patois. In class anyone could break into song at any time.”

The Dunham company was an incubator for many well-known performers, including Eartha Kitt, Talley Beatty, Janet Collins, and Vanoye Aikens. In the 1940s and ’50s, its heaviest touring years, the company visited an astounding fifty-seven countries. Audience response was heady. Dr. Glory Van Scott, who danced with the company in 1959 and 1960, says, “Everywhere we went, audiences went crazy. In Paris, we’d do our show, and then we’d go dancing half the night at the Samba Club. The audience loved us so much, they would follow us there. It was unreal.”

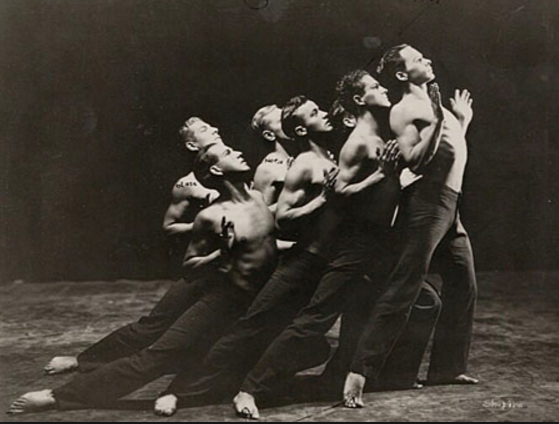

Dunham dancers, 1940s or’50s

But the company encountered racism at home, and Dunham responded with defiance. In 1944, while touring in segregated Louisville, Kentucky, she found a “For Blacks Only” sign on a bus and pinned it to her dress onstage. Afterwards, she declared to the audience that she wouldn’t come back to a place that forbade blacks to sit next to whites.

Southland, with Julie Belafonte at right

In Dunham’s Southland (1951), an impassioned response to the lynchings of blacks, Julie Belafonte played a white woman whose false accusation of rape leads to a black man’s murder. “It was very, very difficult for me,” Belafonte recalls. “I had to transpose my hatred of the character … it was an acting problem. I had to overcome it in myself.” Audience reaction was strong. Says Belafonte, “Everyone in the audience cried when we did it.”

The company premiered Southland in Santiago, Chile, despite warnings from the State Department, which wanted U.S. cultural exports to project only positive images of America. Possibly as a result, Dunham did not win support from the department, which funded tours by Martha Graham, José Limón and Paul Taylor. (In the days before the National Endowment for the Arts, this was the only program that sponsored international dance touring.) But another possible reason is that the State Department’s dance panel called her work “torrid.”

Dunham has lived her credo that “all artists are humanists.” Her home in Haiti, Habitation Leclerc, served as a medical clinic—as well as a tourist attraction, with its nightly drumming and dancing—for many years. Having given injections of vitamin B and penicillin to ailing dancers, she administered first aid for parasites and joint diseases. Once a week, local doctors helped her to diagnose and treat patients in exchange for the medications that she could get them from New York.

Dunham moved to East St. Louis, Illinois, during the racial troubles of the 1960s. Despite death threats and bomb scares, she helped a group of black youths by giving them classes in martial arts, drumming, and dance. During that period, the police were picking up young black men as a matter of course. On one occasion, Dunham railed against this racial profiling, getting herself thrown in jail.

While in her 80s, the choreographer made national headlines by going on a hunger strike to protest the U.S. government’s policy of returning Haitian refugees to face starvation and repression in their native land. She was supported in this effort by comedian Dick Gregory, filmmaker Jonathan Demme and the Rev. Jesse Jackson, along with hundreds of other Americans. It was only at the coaxing of Jean-Bertrand Aristide, the deposed and later reinstated president of Haiti, that she ended her fast after forty-seven days.

Asked about her courageous stand, Dunham says simply, “You can’t learn or acquire these things; I think they’re just put in you from the beginning.”

She feels it is an extension of her destiny to teach–“My guiding voices tell me I should teach, and that’s what I’ve been doing my entire life.” The Dunham technique is being taught all over the country. McBroom-Manno, who has taught Dunham technique at Adelphi University, The Ailey School, and now at the 92nd Street Y DanceCenter in New York, says, “I teach Dunham technique as a way of life. Nutrition, African-based religions and social conscience are all part of it.” Walter Nicks and Romero keep the Dunham technique alive in Europe, while McBroom-Manno passes it along in the United States.

“Everybody is an anthropologist,” Dunham says.

Dunham, 1940s, (Courtesy Special Collections Research Center, Morris Library, Southern Illinois University Carbondale)

“My objective is to see that different cultures get to know each other.” McBroom-Manno relates how, as a scholarship student getting free lunch at the school, she was required to learn the traditional Japanese tea ceremony. “We would be squirming and carrying on, but she wanted us to learn the serenity and silence of that tradition.” In preparing for Aida (1963), McBroom-Manno and the rest of the cast, dancers from both Dunham’s group and the Metropolitan Opera ballet company, studied karate at the Dunham school to perfect a processional before the African king.

Dunham’s influence is global. She helped to train the Senegalese National Ballet, and her performances inspired the start of many national groups, such as Ballet Folklorico de Mexico. Her numerous awards include a 1968 Dance Magazine Award, the Kennedy Center Honors, the American Dance Festival Scripps Award, the Albert Schweitzer Award and, just this spring, the Duke Ellington Award.

She is still concerned about Haiti. During a May 25 interview, she was gratified to hear that very day that Haiti had held free elections without incident.

But her thoughts linger on the art of dance. “Dance has been the stepchild of the arts for a long time. I think now it’s time for it to take its place among the other arts.”

It is also time for Katherine Dunham to be honored as one of the great innovators in the field of dance and one of the great humanitarian artists in history.

Dunham, seated with Melony McGant, and friends, Boule Blanche, Riverside Church, c. 2004. From left: Reginald Yates, me,

Louis Johnson, Mary Hinkson, Terry Carter, Micki Grant, Stanley Strohman, Glory Van Scott, Ruby Streate, Madeline Preston, and Congressman Charles Rangel.

Historical Essays 4