Nacho Duato and the Graham company are an inspired pairing. Although Duato told me in this interview that he enjoyed working with the Mikhailovsky Ballet dancers, I imagine he missed the earthy quality that is so central to his choreography. And lord knows the Graham company needs new choreography. Rust, the piece he made on the group’s men last year, sears your soul with its images of torture. (Sorry, but we won’t be seeing it at City Center this season.) His world premiere, as shown in progress at Guggenheim Works & Process a couple weeks ago, is also intense. Titled Depak Ine, it has insect motifs like scrunching, belly-to-the-ground twitches. A gripping solo for the astounding PeiJu Chien-Pott, a new dancer from Taiwan, is worth the ticket price alone. The season also includes Clytemnestra (with the glorious Katherine Crockett), Appalachian Spring, and a world premiere by Andonis Foniadakis. March 19–22 at NY City Center. Click here for tickets.

In NYC Uncategorized what to see Leave a commentMonthly Archives: March 2014

One of Twyla Tharp’s breeziest, most feel-good works, Baker’s Dozen will be performed by Juilliard students next week. The piece, made in 1979 for 12 dancers, has an innocent polymorphous pleasure that predates the combative seductiveness of the more familiar Nine Sinatra Songs (1982). The piano music, by Willie “The Lion” Smith, will be played live by a Juilliard alum—one of the pluses of going to a dance concert at Juilliard. Another plus, of course, is that you get to see serious students who are already at a professional level. They regularly perform works by current choreographers, and this program is no exception. Accompanying Baker’s Dozen is Lar Lubovitch’s classic group work, Concerto Six Twenty-Two (the one that contains his beautiful male-bonding duet made in the time of AIDS) and Eliot Feld’s fun romp The Jig Is Up. March 21–25 in Juilliard’s Peter Jay Sharp Theater. For more info click here.

In NYC

Rebekah Morin as Red Queen. Photo by Adam Jason

At the beginning of Then She Fell, an immersive performance in a Brooklyn church, a man playing “the doctor” reminds us of all the meanings of the word falling: Falling down the stairs, falling ill, falling in love. The audience of 15 is sitting in a tiny room in a Brooklyn church. This little speech, delivered by a young man so cluelessly serious he put me in mind of Professor Peabody of Rocky and Bullwinkle, helps us feel like we are entering pleasantly endangered territory. The mysterious wines and liqueurs we are offered also help.

The dancers playing Alice, the White Rabbit, and the Mad Hatter—even the Red Queen—are not as intense as the characters in Sleep No More, the more blockbuster example of the new immersive theater. There is no violent thrashing against ceilings or murder in a bathtub. But the smaller, quieter, Bessie Award-winning Then She Fell, has its own rewards. First of all, audience members get to be themselves, not masked. You are guided here and there like a patient in an elite hospital, and it gradually dawns on you that you are part of the performance. You are not one of the white masked masses that surge through Sleep No More, but you might be just a windowpane away from the Red Queen grabbing her bottle of pills. Or you might be invited to play poker with—was it the doctor?—after he tells of a dream where the streets keep changing.

Then She Fell, with Marissa Nielsen-Pincus and Tara O’Con as the two Alices. Photo by Rick Ochoa

Secondly, there is a literary component that comes at you in fragments, and it’s left to you to connect the bits and pieces. With more than 20 rooms and audience members being led in different directions, you don’t encounter the same scenes as your fellow spectator. One scene that hooked me was where the two Alices almost merge in a two-way mirror, reminding me of the haunting, identity-confusion scene in Bergman’s film Persona. Another was the Mad Hatter giving dictation in a room littered with thousands of such failed attempts. He tries to dictate a letter, scampering nervously all over the room, never getting beyond the first few words. The letter seems to be about a break between Carroll and Alice. (We learn earlier that her mother put an end to his visits.) As the woman taking dictation tries to get it right, I am reading some of the myriad scrapped letters that have accumulated in piles—traces of many shows past.

The intriguing thing was hearing and seeing bits of writing by Lewis Carroll. You get a sense of the weirdness of Carroll’s obsession with Alice but also the vastness of his literary output.

Tom Pearson as White Rabbit and Rebekah Morin as Red Queen. Photo by Rick Ochoa

While the story of Lewis Carroll and his young friend Alice is one cornerstone of Then She Fell, the site itself is another. The piece was first produced in a hospital (thus the doctor) but it moved to this site, The Kingsland Ward at St. Johns, last year. The building housed Occupy Wall Street a century after it was built. Tom Pearson, one of the three originators (the other two are Zach Morris and Jennine Willett) said to me after the show, “I love the architecture, the culture of what’s underfoot, the smells and touch. We call it all topography and it grows roots in all directions.”

I don’t understand the math, but with audiences of only 15, and a cast of about 8 doing two shows a night, somehow this production is holding its own financially. Happily, it is here to stay for months to come.

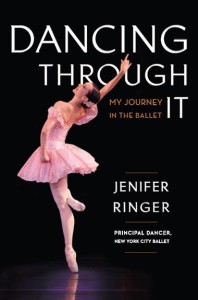

Featured Uncategorized Leave a commentThere’s a moment in Jenifer Ringer’s book, Dancing Through It: My Journey in the Ballet, when she is so desperate that she contemplates suicide. She’s tried again and again to solve her eating disorder, which led to losing her job at New York City Ballet, and she feels like an utter failure. What saved her, in that dark moment, is the awareness of the pain her death would bring to her parents and sister. Needless to say, one of the reasons to read her terrific book is to learn how she pulled herself out of that abyss.

I know, from the suicide attempts of people close to me—both successful and blessedly unsuccessful—that what goes out the window in those darkest moments is any thought of one’s loved ones. (Or, in temporary twisted thinking, the notion might be, “They’d be better off without me.”) Every thought crowding around the person is simply, and only, about how to release themselves from a life that has become unbearable.

Philip Seymour Hoffman

In Michael Feingold’s recent column in Theater Mania, he comes to a similar conclusion. Prompted by the death of actor Philip Seymour Hoffman, he is trying to understand the addictive personality. He contrasts that type of person with artist in the theater who have lasted a long time, giving the example of the 90-year-old lyricist Sheldon Harnick. Of course, addiction is complicated and an overdose such as Hoffman’s may be accidental. But in general, Feingold sees that, at the other end of the tunnel, there needs to be some feeling that you matter to those close to you. If there is a secret to survival, he says, it is “the simple awareness of others’ concerns.” Sadly, that awareness is sometimes beyond the reach of someone who’s been pulled into a downward spiral.

Depression has long been a hazard for artists. I found this in Tchaikovsky’s letters, from 1876:

Tchaikovsky

“Sometimes for hours, days, weekends, months, everything looks black; it seems that you are abandoned by everyone, left alone, and no one loves you. But I explain my state of despondency, my weakness and sensitivity, by my bachelor state and absolute lack of self-denial. To tell the truth, I live following my vocation as well as I can, but without being of any use to individual people. If I should disappear from the face of the earth today, maybe Russian music would lose something—but surely no one would be made unhappy. In short, I live the egoistic life of a bachelor. I work for myself, think only of myself, aspire only for my own welfare. This is very convenient, but it is dry, narrow, and deadly.”

Featured 1Talk about breaking the fourth wall—Faye Driscoll broke all the walls and the floor last weekend! And she’ll do it again this weekend.

Her piece Thank You for Coming starts with five dancers smashing body parts against each other—fingers crunching a cheek, a knee poking into a neck. There is something childlike in they way they disregard, and yet take pleasure in, the flesh of the person next to them—or on top of them. This is happening on a low platform in the middle of the St. Mark’s Church sanctuary. Tethered to each other in a sensual hell/heaven, they reach out to us beseechingly. Should we help them? Will they pull us under? Will we get stuck in the same frantic playground they are mired in?

Thank You for Coming, Faye Driscoll sliding under the platform, photo by Aram Jibilian

At some point Faye Driscoll entered the space and slipped under the platform. I thought she would thump on the surface from below. But no. While the five dancers connected in one long, writhing line and rolled down into the audience like a wave washing up on a shore, Driscoll pushed apart the platform from below, breaking it up into segments—that turned out to be separate benches. The floor that was solid enough to withstand lurches, falls, and tackling embraces is now being deconstructed before our eyes. Where do the benches go? They become our new seats—as Driscoll carries each one to the sidelines. Meanwhile that writhing line of humans is slithering out of their T-shirts and shorts into other clothes (shades of Trisha Brown’s Floor of the Forest) with the help of the audience members they landed on.

In their fancier clothes (visual design by Nick Vaughan and Jake Margolin), the dancers now go through manic stop-action motion to effusively greet or skeptically avoid someone. They sustain this hyper—even spastic—mode with superhuman energy for a long time, yet it somehow goes with the mellow guitar played by Michael Kiley.

The space is again turned inside out by a crazy, snaking, bulging intersection of nearly naked dancers and elastic tubing that eventually resolves into, of all things, a maypole dance. Again, Driscoll herself is the subverter and guide, asking people to hold ropes or tubing. And suddenly, the contradictory feelings melt away, the dancers forget their struggle, and an innocent maypole dance ensues, each round gathering more audience members, who by this time are utterly charmed.

Because the dancers were so close to us, because they were so legible in their expressions of contradictory feelings, because the physicality veered toward and away from sexuality, and because you didn’t know what you would be called upon to do, this was the most engaging performance I’ve seen in a long time. With all its anarchy and purpose, it was like the Living Theater of the Sixties.

Thank You for Coming continues this week, March 11 and 13–15. I think it’s sold out, but check out the Danspace website.

Featured Leave a commentI wouldn’t don 3-D glasses for just anyone, but I would for Wayne McGregor. His London-based Random Dance company gives Atomos its American premiere at Peak Performances in NJ. The piece plunges his fierce performers into a visually transforming environment, including 3-D video screens hung from above (I’m trying to picture it), designed by his resident lighting genius, Lucy Carter. I loved Borderlands, their collaboration for San Francisco Ballet, which gave me a reason to interview the brilliant McGregor for Dance Magazine last year. If Atomos has even a fraction of the giddy complexity of Borderlands, I’ll be beyond happy. March 15–23 at Peak Performances in Montclair, NJ—only a half hour from Penn Station. To find out how to get there, click here.

Atomos, photo by Ravi Deepres

Let’s hope there are no more fires in the Harris Theater, as there was before Hamburg Ballet’s date there last month. Chicago’s underground theatre had to cancel performances, sending the 100-person German company packing when an electrical fire broke out. Thankfully, the Harris Theater is under control now—just in time for Hubbard Street’s tribute to Jirí Kylián, that master innovator in Europe. The company performs a gender-balanced program: the all-male Sarabande (1990), the all-women Falling Angels (1989), 27’52” (2002), and—everybody’s favorite sexual fantasy—Petite Mort (1991). Music scores include Bach, Reich, and Mozart. March 13–16. For tix, click here.

UncategorizedIf you’re interested in how other forms of dance infiltrate ballet—and you live near Seattle—check out Peter Boal’s Director’s Choice evening at Pacific Northwest Ballet. He’s got company favorites by (post)moderns Susan Marshall (Kiss) and Molissa Fenley (State of Darkness), and TAKE FIVE…More or Less by musical theater mastermind Susan Stroman. What’s new? A world premiere by Alejandro Cerrudo, everyone’s favorite tall, skinny Spaniard, who can flip between classical ballet (silky pirouettes) and modern (large scooping moves), as he did for Wendy Whelan’s Restless Creature. March 14–23. Click here for tix.

James Moore & Mara Vinson in Marshall’s Kiss. Homepage photo is of Stroman’s TAKE FIVE, with Kaori Nakamura; both photos © Angela Sterling.

Lightbulb Theory, photo by Julie Lemberger

For the second half of the Harkness Festival, Doug Varone has chosen signature works by two of our most risk-taking choreographers: Kyle Abraham and David Dorfman. While Abraham’s Radio Show (March 14–16) gives us a beguiling rendition of gender fluidity, Dorfman’s Lightbulb Theory (March 21–23) revels in his sly, self-effacing humor and all-out, rough-and-tumble partnering. (To get a glimpse of his sense of humor—and doom—see his Choreography in Focus.) At the 92nd Street Y. For tickets, click here.

In NYC what to see