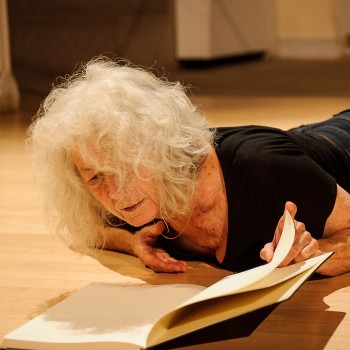

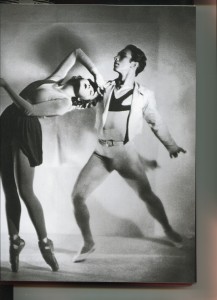

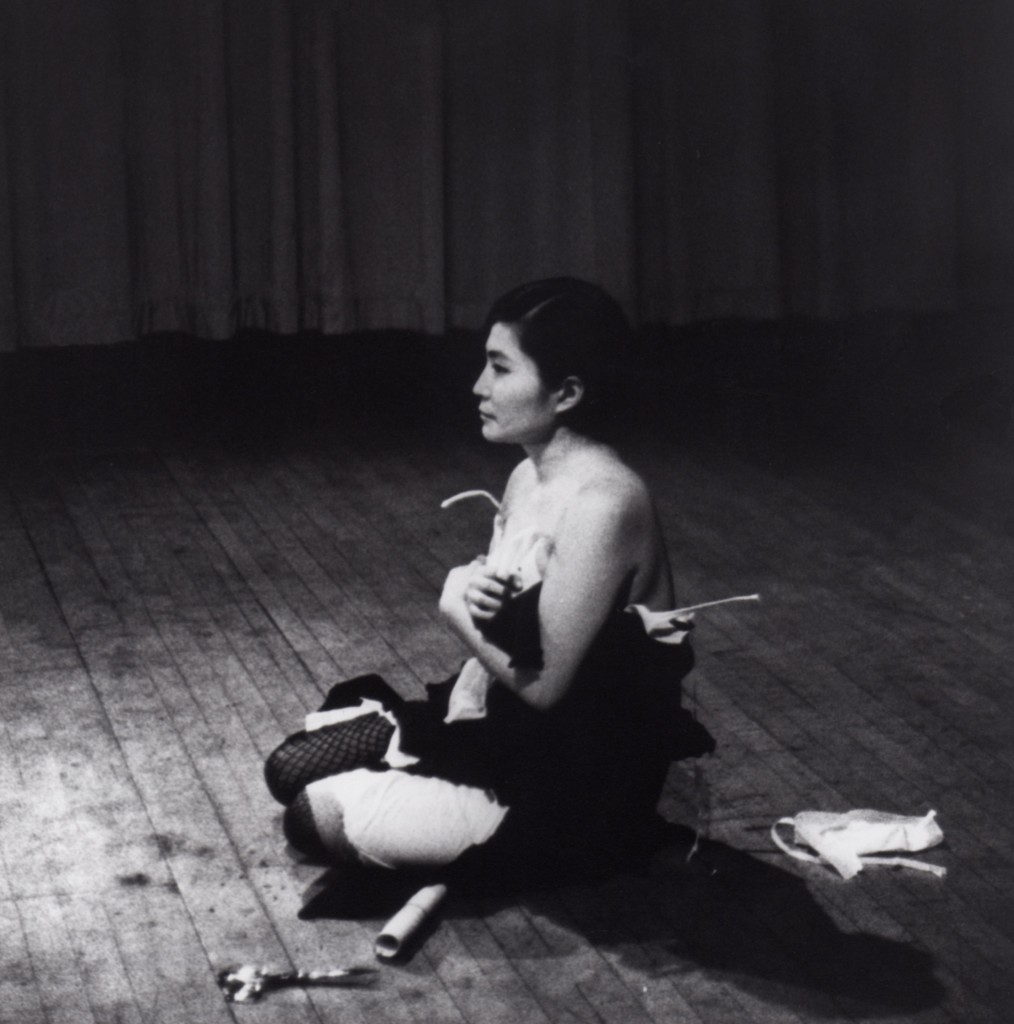

What a revelation MoMA’s exhibit of Yoko Ono’s early work is! Just watching the film of her Cut Piece from 1965 is astonishing. She sits on the floor with a pair of scissors at her side. Audience members are invited to walk up to her and cut a piece of her clothing off—a simple task, laced with sexuality and danger. All the while she sits still, her face a mask of zen-like awareness—composed yet vulnerable, intelligent yet helpless, modest yet brazen. In using her own body as part of the artwork, she anticipates women artists like Cindy Sherman and Ana Mendieta. Click here for a YouTube clip of Albert Maysles’ film of Cut Piece.

Yoko Ono in Cut Piece (1964) Carnegie Recital Hall, 1965. Photo

© Minoru Niizuma. Courtesy Lenono Photo Archive

The Dawn of Performance Art

Not unsurprisingly, Cut Piece was named by The Guardian one of the 10 most shocking performance pieces ever. . But I am interested in it less for its outrageousness and more for its connection to dance and performance art. It was not unlike some of Anna Halprin’s work of the ’60s, for example, the slow sequence in Parades and Changes in which the performers are dressing and undressing while focusing steadily on another person.

That kind of gaze became known as the downtown “neutrality.” I’ve seen a similar combination of guts and neutrality in work by Yvonne Rainer, and the combination of a simple structure with sensuality in Simone Forti’s work. Rainer and Forti (both of whom had studied with Halprin), were colleagues of Ono’s in the early ’60s, sometimes performing in the same shows.

Ono with Bag Piece (1964). Homepage photo of Ono with Apple, both photos at MoMA by Ryan Muir

Another interactive performance piece, called Bag Piece (1964–2015) is based, touchingly, on her own shyness. The instructions are for two people to go under the bag, take their own clothes off, put them back on, then emerge from the bag. In the display type, she writes, “I didn’t know how to explain to people how shy I was. When people visited I wanted to be in sort of a box with little holes where nobody could see me but I could see the m through the holes.”

Talking About Crotch Aesthetics

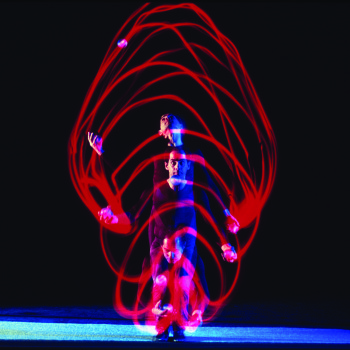

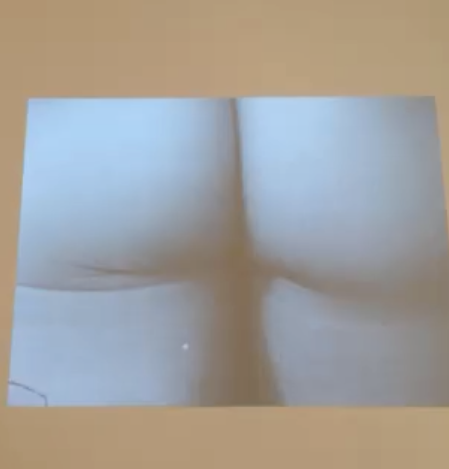

Still shot of Film No. 4

I recently posted my musings about the new frankness of what I call crotch aesthetics. But I realized when I saw this exhibit that Ono was way ahead of today’s artists in her crotch derring-do. In Film No. 4, she filmed nude people walking away from her, one at a time, the camera trained on the lower rear end. You get to see how different people move their buttocks as they walk.

The John Cage Influence

Many of the artists in Ono’s milieu were inspired by John Cage, whose famous composition class at The New School she sometimes attended. He challenged the separation of music and theater and, even further, the separation of art and life.

In the early 60s, that cross-discipline spirit was fostered in Ono’s loft on Chambers Street, which soon became a hotbed of hybrid work by musicians, visual artists, and dancers. Forti created a landmark evening called “Dance Constructions” there in 1961. In it she presented her now-classic works like Huddle, Slantboard and Roller Boxes.

Just as Judson Dance Theater was an offshoot of John Cages’ teachings (via Robert Dunn), Ono was an offshoot in a different direction. Already possessed of an idiosyncratic imagination that knew both pleasure and pain on a cosmic level, she extended his idea that any sound can be music to any action can be art. In the new book John Cage Was, she acknowledged his influence by beginning her contribution with this claim: “The history of Western music can be divided into B.C. (before John Cage) and A. C. (after Cage).” The respect was likely mutual. Cage, who himself was influenced by Asian ideas, had dedicated a piece of music to Ono.

A taunting kind of playfulness infuses the current exhibit, officially called Yoko Ono: One Woman Show, 1960–1971. That too is in line with Cage’s endearing optimism. You only have to go as far as Twitter to find further examples of that quality. She recently tweeted, “Be playful. Dance with your mind and body. It’s such fun that ‘They’ might start to dance with us, too!”

The Prank Became Real

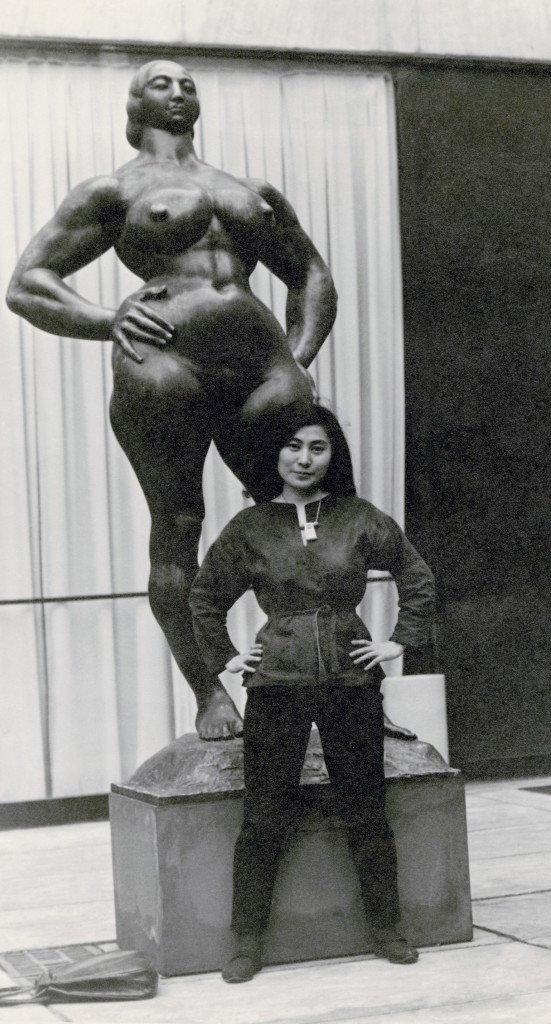

Ono with Standing Woman (1932) by Gaston Lachaise, MoMA, c. 1960–61, Photo © Minoru Niizuma, Courtesy Lenono Photo Archive

Cut Piece was one of the few performances Ono made. More often she created suggestions for a performance or exhibit rather than the thing itself. Take for instance her semi-fictitious announcement of a one-woman show at the Museum of Modern Art in 1971. She sent out publicity, took out ads, and made an elaborate catalog of a show that consisted only of a statement that a jar of flies drenched in Ono’s perfume had been released at MoMA and people were following the flies all over the city. Now, more than 40 years later, that ridiculous prank has led to a one-woman show. And it’s a spectacular, provocative, many-layered experience.

Her Rising Stature

Although I’ve always been dazzled by Ono’s gifts (I chose her song “Walking on Thin Ice” for my choreography once), this exhibit transforms her in my mind from a marginal music maker and conceptual artist to a major figure in 20th century art. The exhibit encompass 125 drawings, posters, objects (including a whole room in which all the furniture is cut in half) , audio recordings, films. Everything, whether an instruction piece or an object, are exercises in expanding the imagination.

Half-A-Room (1967)

One could view her 2013 music video of Bad Dancer, in which she’s not a bad dancer at all (at the age of 80), as an update of her ’60s ideas. It combines painting, costume design, music and dance, and has garnered over a million hits.

Capsules of Infinite Imagination

What we take away from Yoko Ono: One Woman Show, 1960–1971, is a restless, curious mind that puts fantasies in the form of challenges, riddles, or haiku. Many of the verbal riddles and instructions come from the pages of her book Grapefruit, which was written between 1961 and ’64. I will leave you with three examples from this collection of enigmatic instructions.

One page was written for Robert Morris, who was married to Simone Forti at the time.

“Find a stone that is your size or weight.

Crack it until it becomes a fine powder.

Dispose of it in the river.

Send small amounts to your friends.

Do not tell anybody what you did.

Do not explain about the powder to the

Friends to whom you sent it.”

Another page was written as “Voice piece for soprano”:

“Scream

- against the wind

- against the wall

- against the sky”

Lastly, Dawn Piece:

“Take the first word that comes across your mind. Repeat the word until dawn.”

Featured Uncategorized Leave a comment