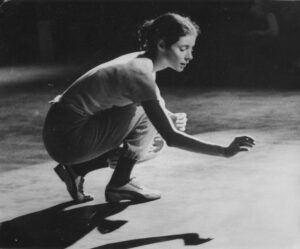

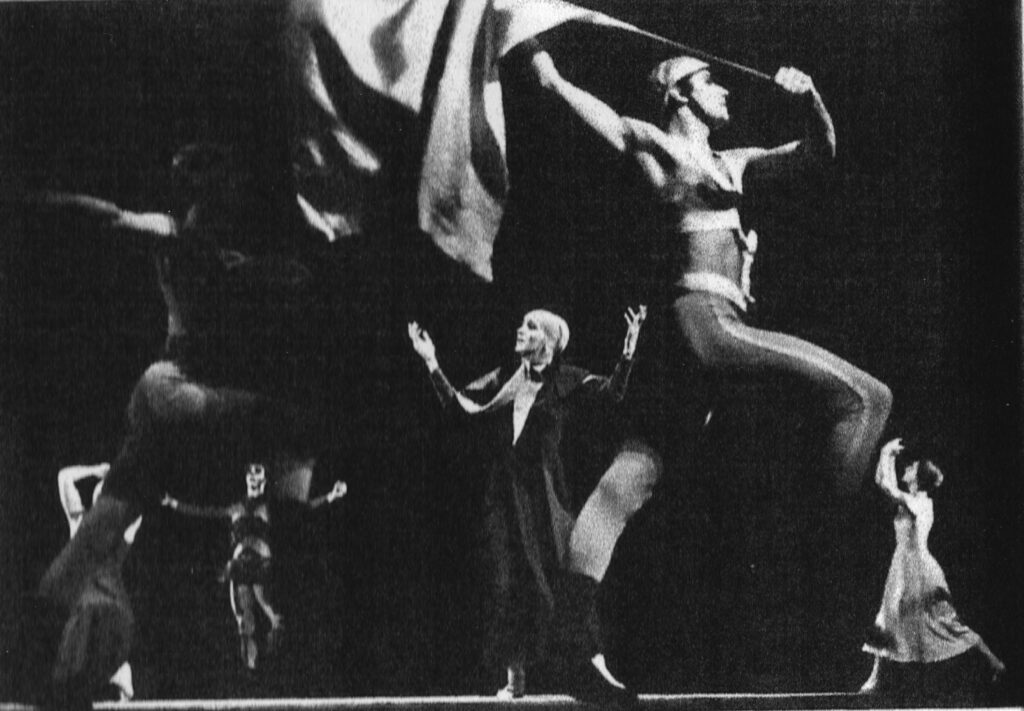

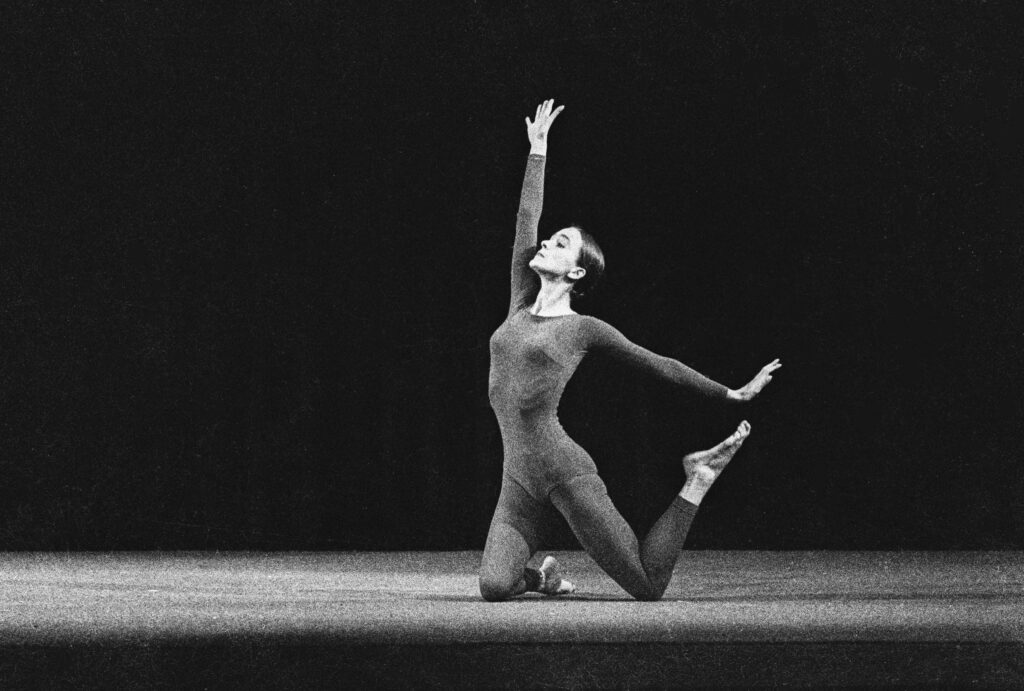

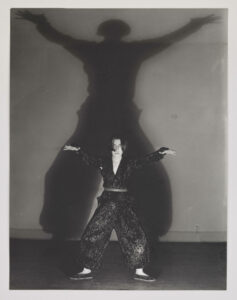

I will never forget Rudy Perez performing Countdown in 1968. If the word “riveting” did not exist, it would have to be invented for that performance. Sitting in a chair, his feet rooted to the ground, his focus unwavering, he took a super slow-motion drag on a cigarette. He slowly stood up, and without breaking his tempo, streaked his cheeks with green paint. Were they tears? Were they war paint? The recorded music of the “Songs of the Auvergne” transported us to a faraway place. Rudy was perhaps remembering something beautiful that arrested his everyday action. Countdown was also an example of radical juxtaposition, a term I didn’t know then, which describes a dada-esque collision of opposites that forces the viewer to create their own cogency. (It was a term Yvonne Rainer borrowed from Susan Sontag.) His work also had a whiff of satisfying absurdism. Of course Rudy never used such terms to describe his choices.

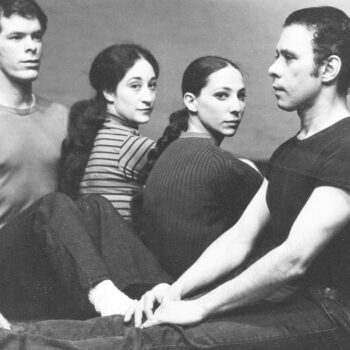

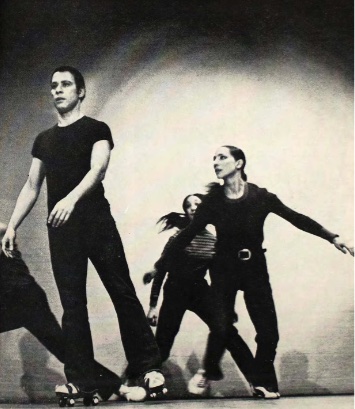

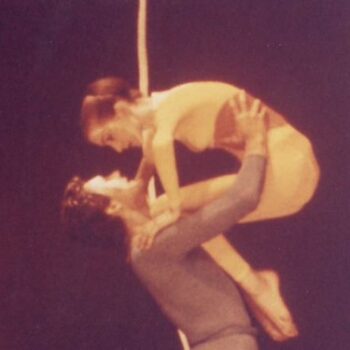

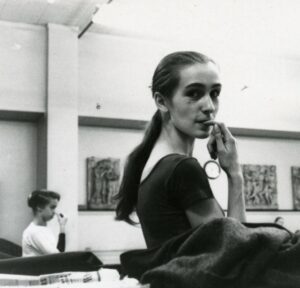

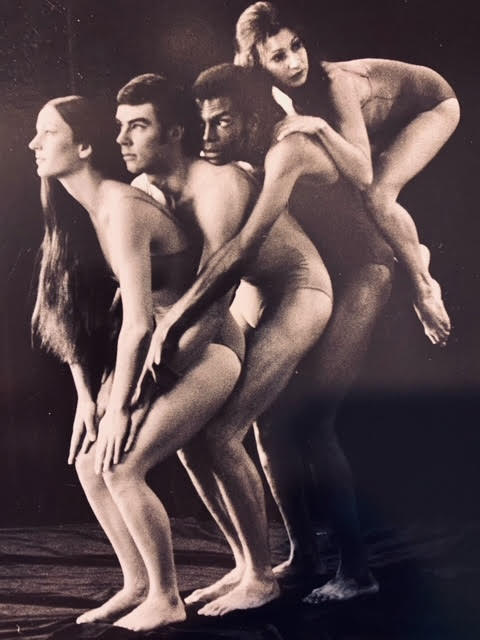

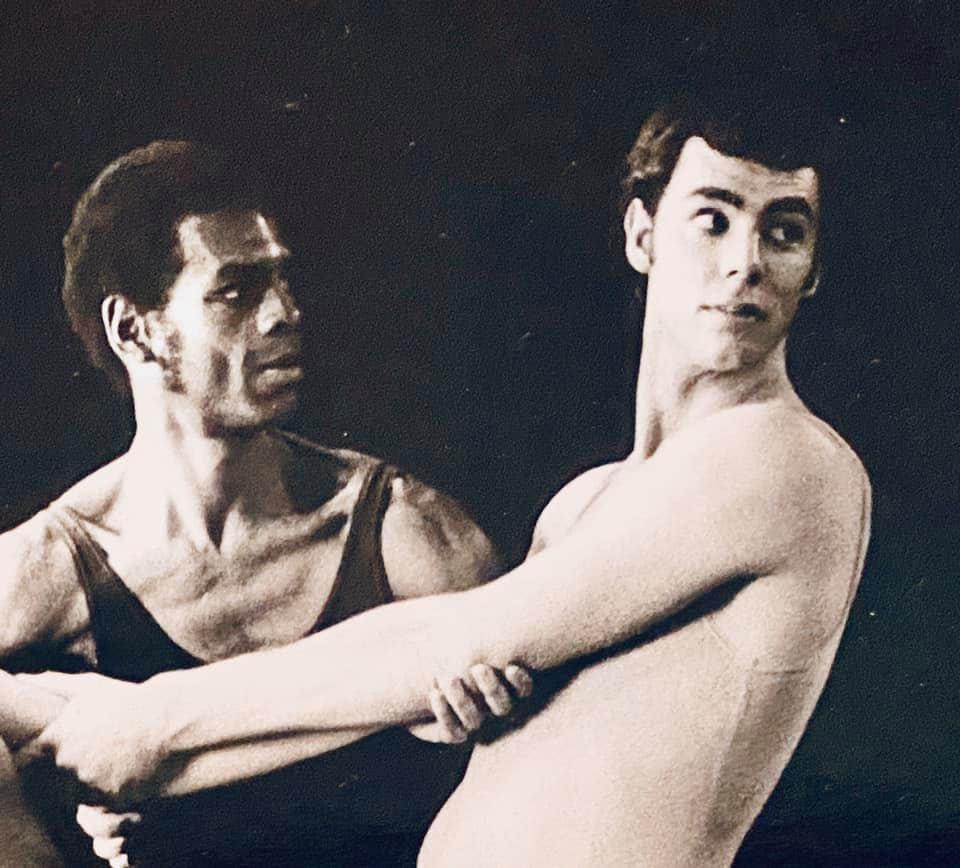

The place where I saw Countdown was the old Dance Theater Workshop, which was Jeff Duncan’s living space on West 20th Street. Later, in the fall of 1969, also at DTW, I was showing a solo of mine to Jeff Duncan for a program of what is now Fresh Tracks. Rudy had just finished rehearsing and decided to hang out and watch my solo. A few weeks later, I ran into Rudy in a local supermarket on the Upper West Side, and he invited me to join his tiny company. Having been knocked out by Countdown, I said Yes. I danced with him for a year, enjoying performing with the magnificent Barbara Roan, the delightful Anthony La Giglia, and being challenged by Rudy’s sturdy movement and uncompromising vision.

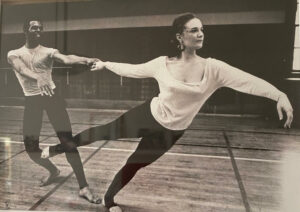

In 2019, the Stephen Petronio Company revived Rudy’s Coverage, a solo he made during the time I was dancing with him. When Siobhan Burke wrote an advance article for the New York Times, she asked me to describe what was unique about Rudy’s work. She quoted me describing his approach: “He had this instinct for what would work next to each other. We’d be doing something rigid and stiff, then suddenly we’d be bending down and picking flowers in a dreamlike slow motion…There was something very sure and magical about what he did onstage.”

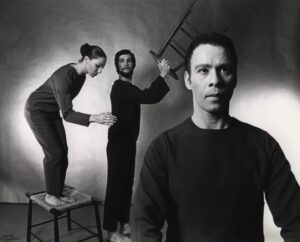

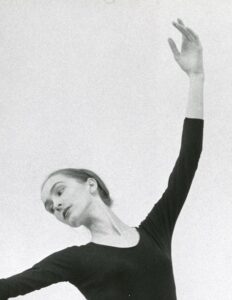

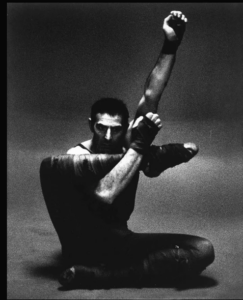

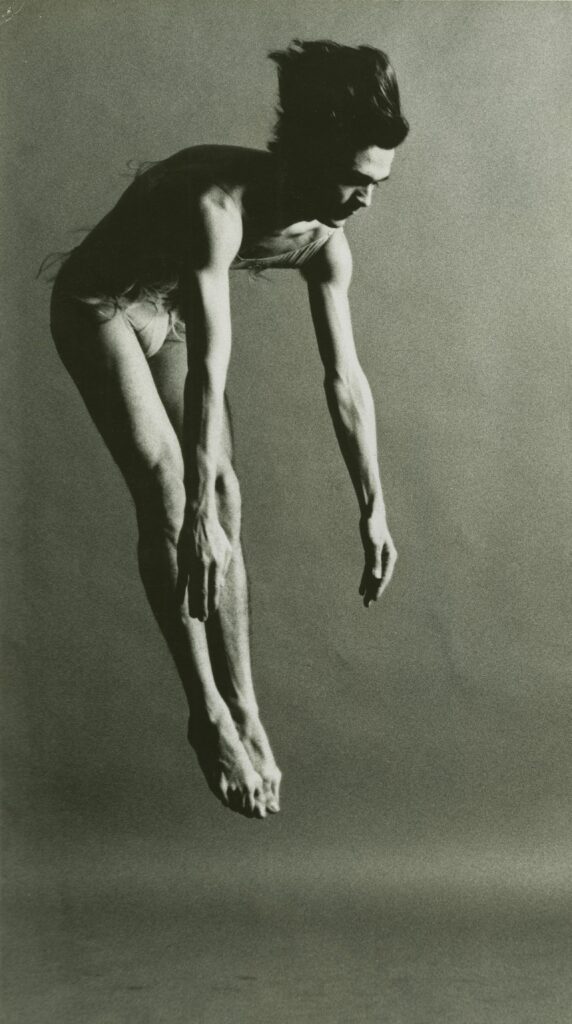

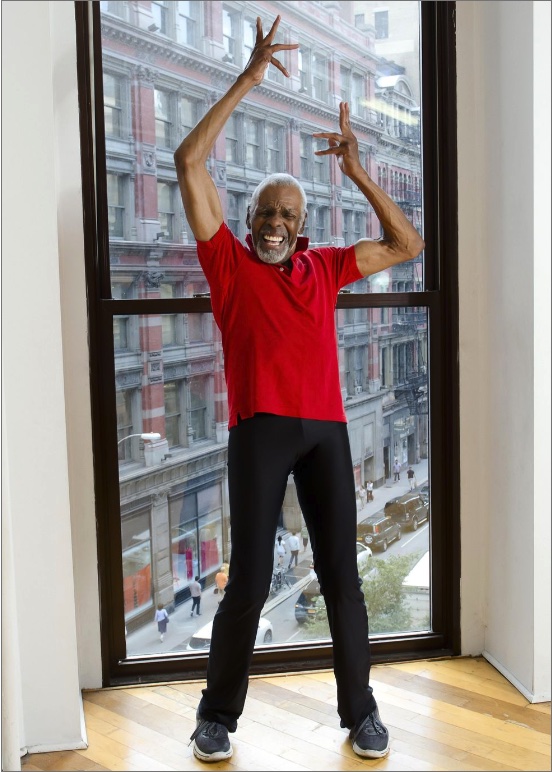

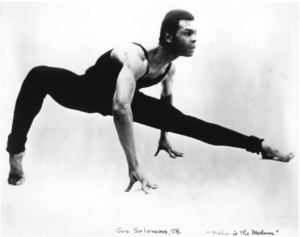

Although Rudy was a strong and energetic dancer, he did not have what was considered a dancer’s body. He told me that he realized he’d have to make his own work if he wanted to dance. This, I think was a strength: He created his own aesthetics.

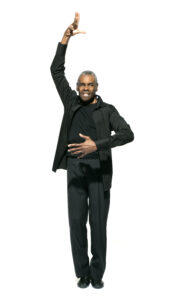

When Don McDonagh’s book The Rise and Fall and Rise of Modern Dance came out in 1970, I was excited because he highlighted dance artists from Judson and DTW—people I had danced with—as the ones who were raising modern dance up again in the Sixties. In his chapter on Rudy, he described the choreographer’s “vibrant stillness.” He also wrote that Rudy was “the most emotively charged dance maker of his generation, but his emotionalism is strictly controlled and measured out in carefully placed spurts of movement.” The elements of his choreography were “meticulous workmanship, unusual juxtapositions of visual and aural material, and a weighty intensity.”

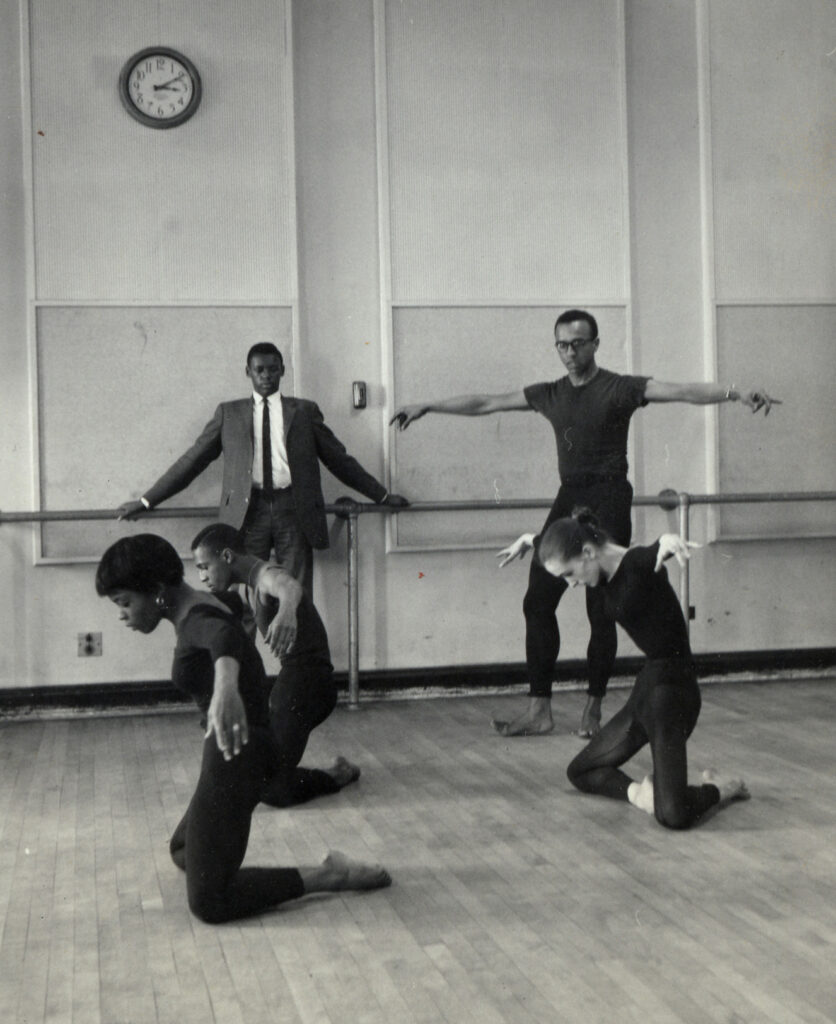

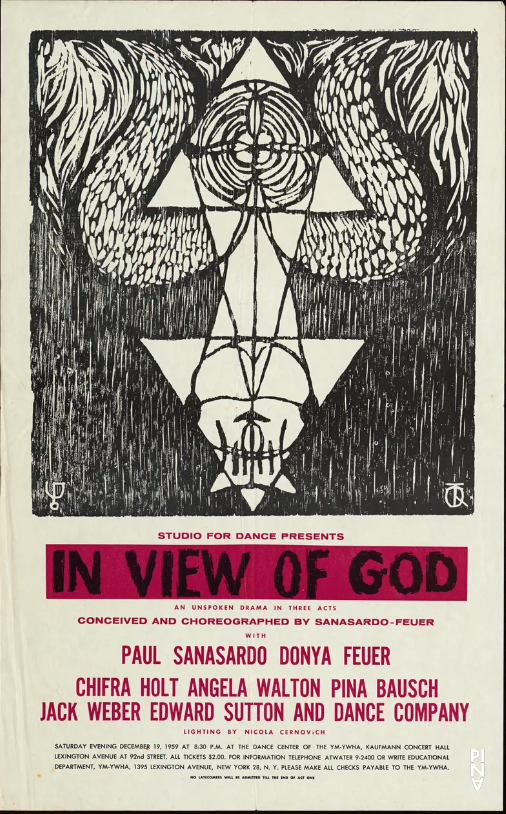

Rudy was the first person I heard talk about Judson Dance Theater. He had attended some of Robert Dunn’s workshops and had participated in Judson concerts from day one. Judson became a huge topic of interest to me. Just hearing the name Judson helped me trace where Rudy got his exquisite simplicity from. When I started teaching at Bennington in 1978, I wanted to expose my students to the experimental spirit of Judson. I created a multi-year project called the Bennington College Judson Project, part of which is archived at the NY Public Library for the Performing Arts. (I also gave a “Dance Historian Is In” presentation on it. If you’re interested, the recording is viewable at the Library.)

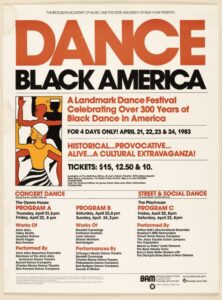

Although Rudy is not often mentioned when Judson is discussed, he is one of the few of that collective who went on to have a multi-decade career in dance. (Others were the obvious names of Trisha Brown, Lucinda Childs, Yvonne Rainer, Steve Paxton, David Gordon.) I’m glad he found his niche in Los Angeles, but he drifted away from New York consciousness. Our loss was L.A.’s gain. Marcia B. Siegel called him “one of the quiet experimenters in whose hands I think the future of dance will rest.” At least two of his students there went on to create their own dance worlds: Victor Quijada of RubberbandDance and Chris Yon, now at Appalachian State University.

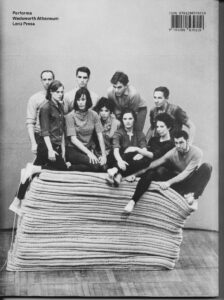

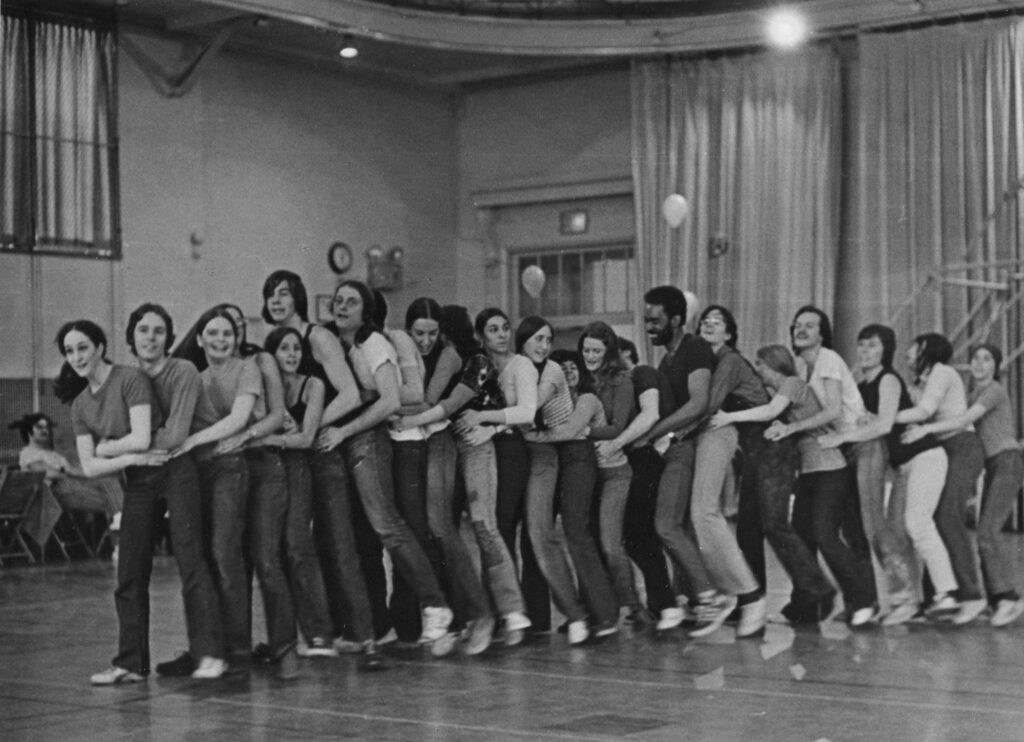

Conga line in one of Rudy’s pieces, c. 1971, led by Wendy Summit. Find Jane Comfort, ninth from the end. Ph unknown

In an article in the June 1971 issue of Dance Magazine, Rudy explained his process: “My work begins as a collection of images, but when it is finished it must be a whole, loose parts of experience making up a whole. It’s like a jigsaw puzzle, trying to fit things together so that when it’s finished, it’s complete.”

Thank you, Rudy, for your completely remarkable work.

And thanks to Sarah Vox Swenson for setting up the memorial page of the website devoted to him.

Featured 1