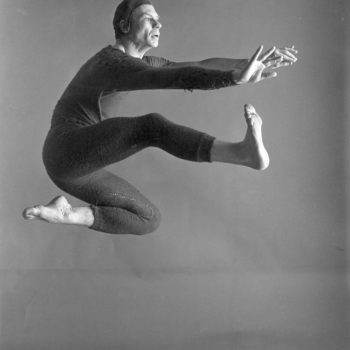

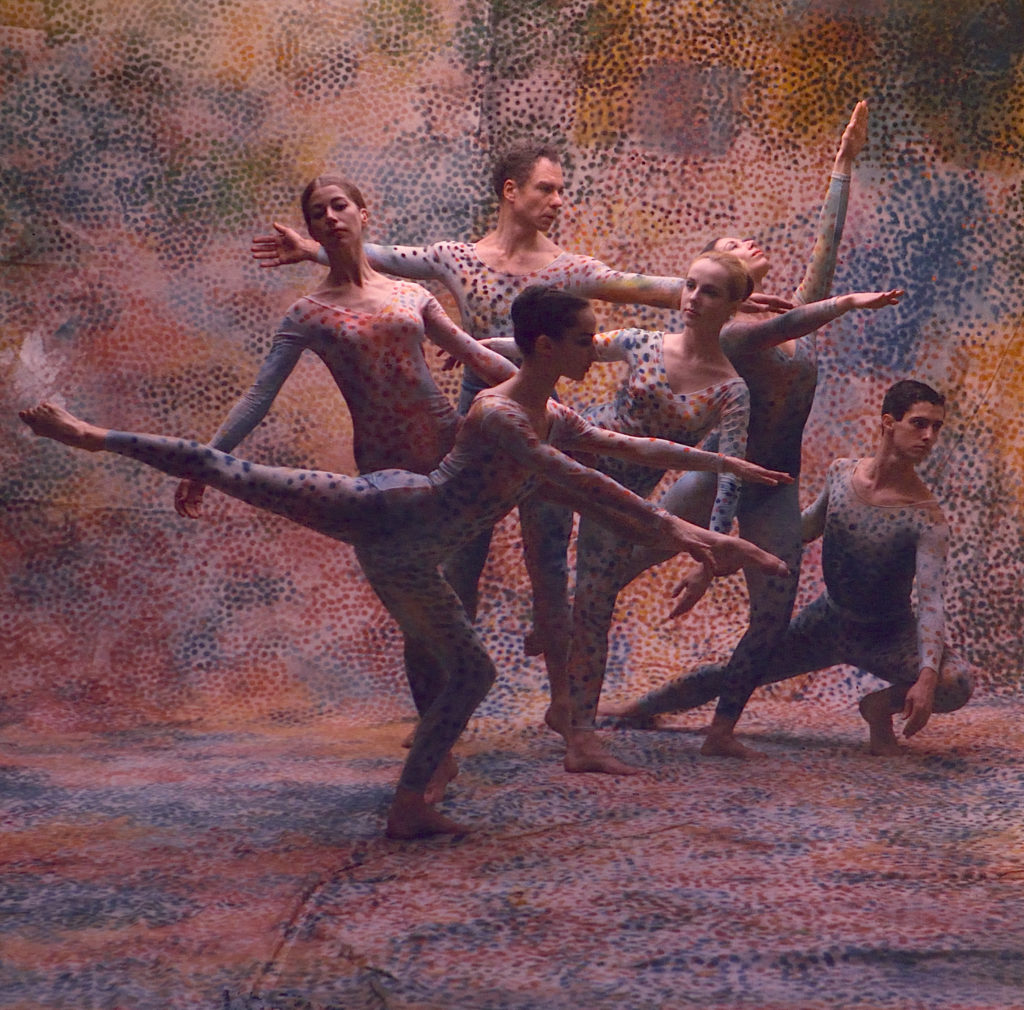

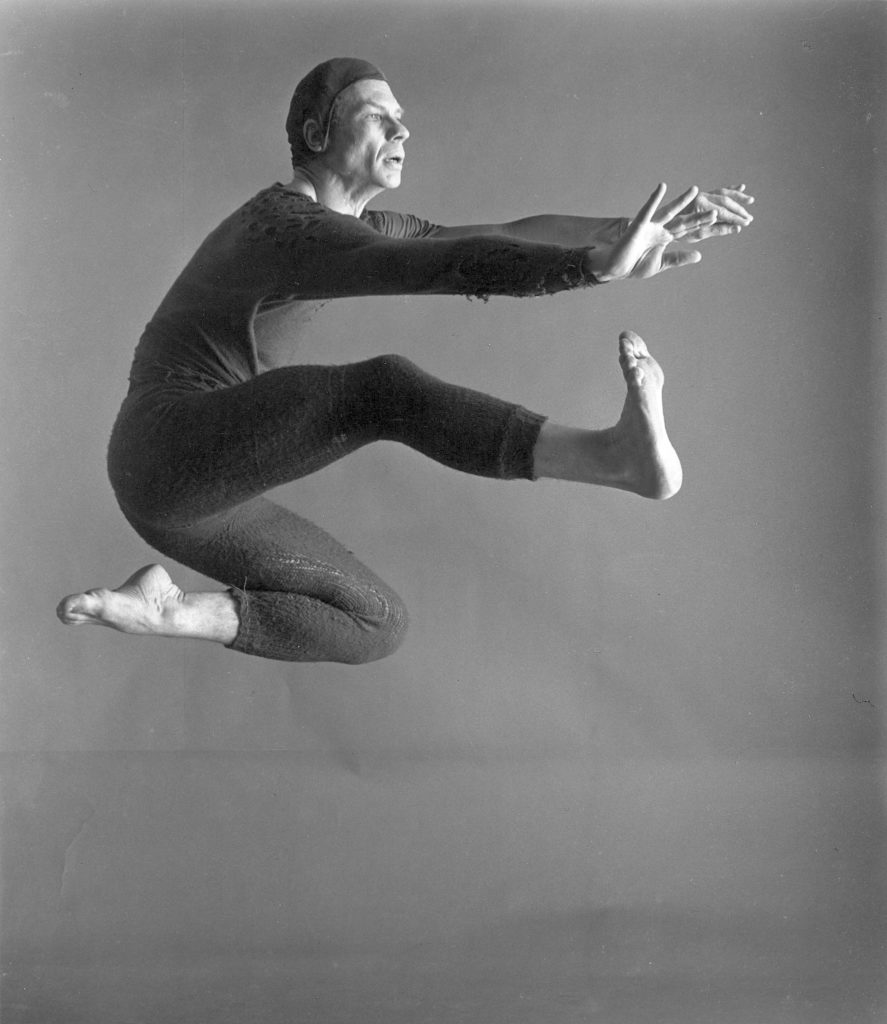

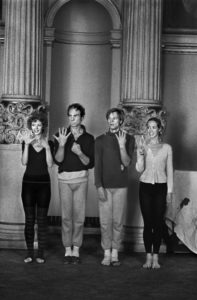

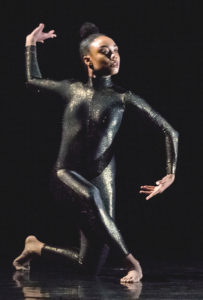

Ishmael, Ralph, Bebe, all photos by Nathan Keay via MCA Chicago

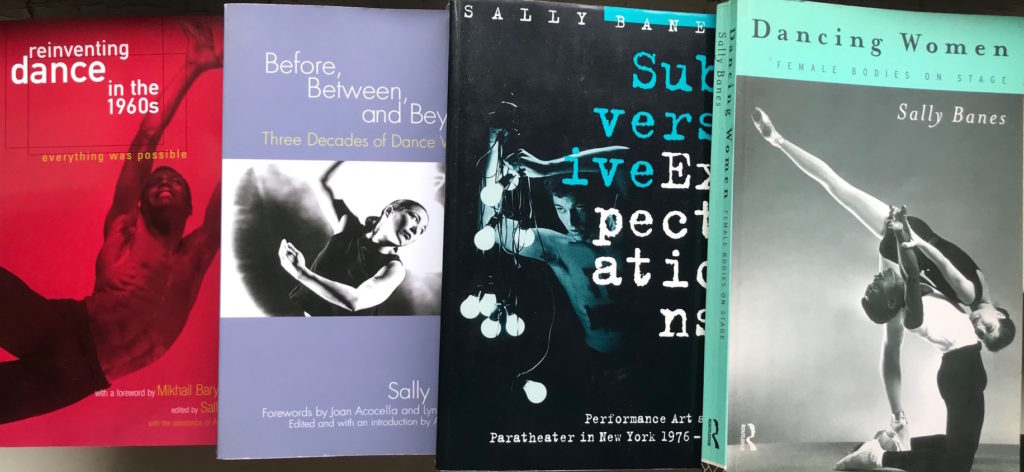

When it was announced that Ishmael Houston-Jones, Ralph Lemon, and Bebe Miller would perform together, it seemed too good to be true. Three of our greatest mischievous/masterful dance artists improvising together!

And it wasn’t true—at least not for New Yorkers. Relations was only true for the lucky people in Chicago. The presenter was MCA Chicago, the curator was Tara Aisha Willis, and the dates were November 2–3, 2018.

Last week Tara organized a virtual watch party of the second performance, and it will now remain posted until July 31. I was thrilled to see the video. There’s a certain feeling of alert anticipation when you watch really good improvisers in live performance. And somehow this video did not seem like a document but seemed alive to me.

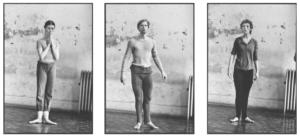

Ralph, Bebe, Ishmael

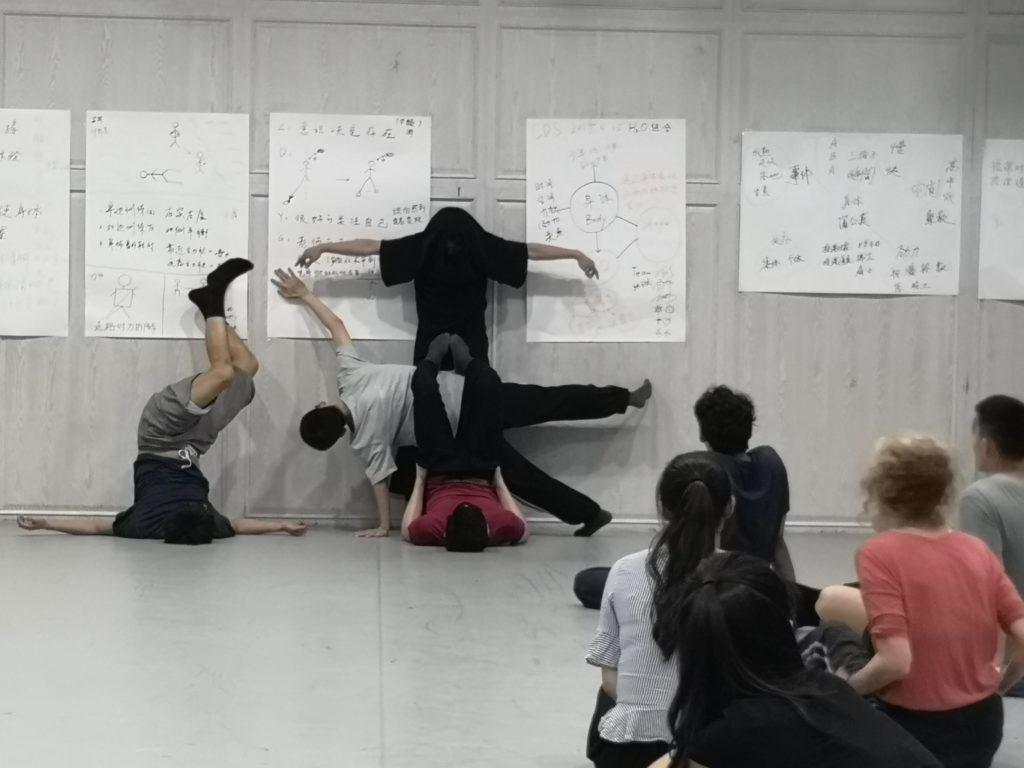

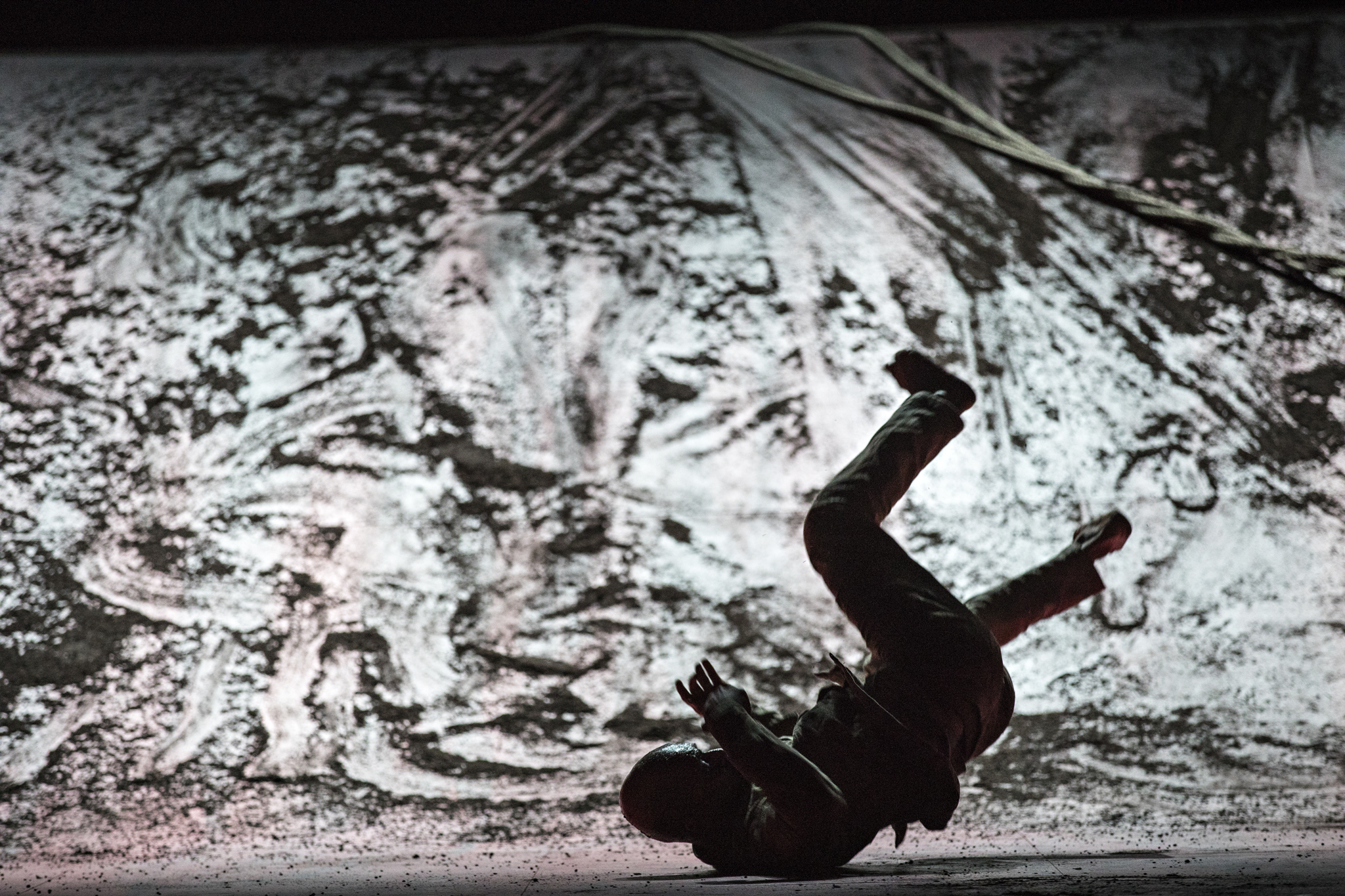

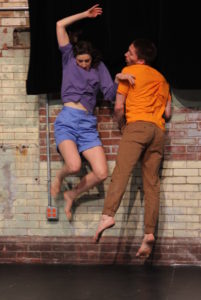

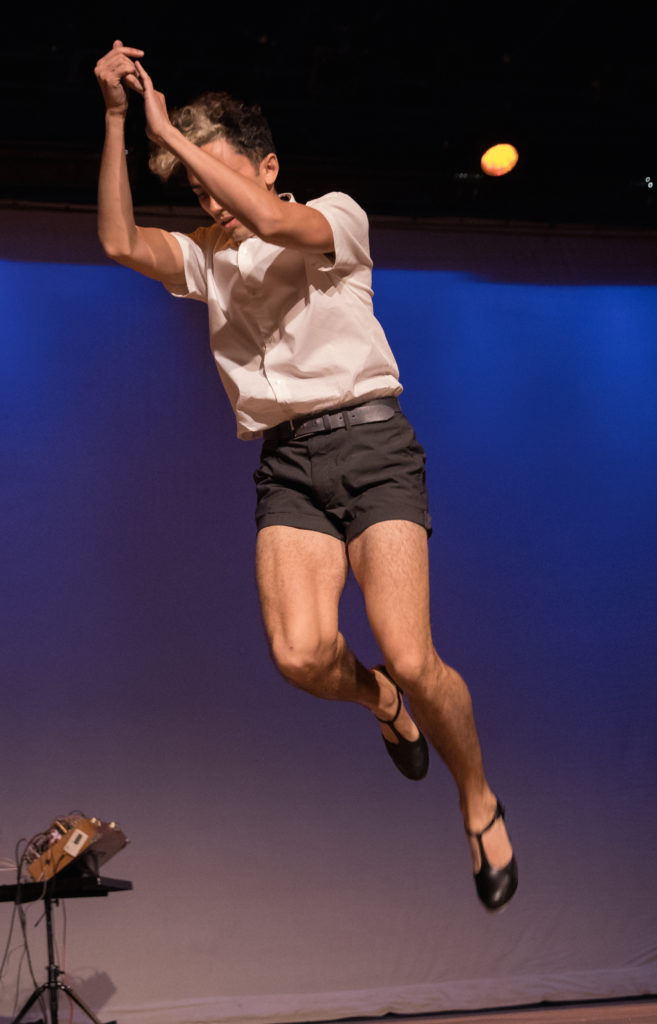

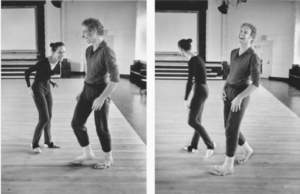

Three is a good number. Three people who are natural leaders agreeing to enter a leaderless arrangement. One is always in Relation to the other Two, as well as being in relation to a slat on the floor, or to a chair, or to a stash of records. I had that anything-can-happen sensation, that sitting-on-the-edge-of-my-seat feeling, while also noticing how centered in their bodies and how conscious of their decisions they seemed. It doesn’t hurt that they are all, bottom line, terrific movers.

Ralph, Bebe, Ishmael

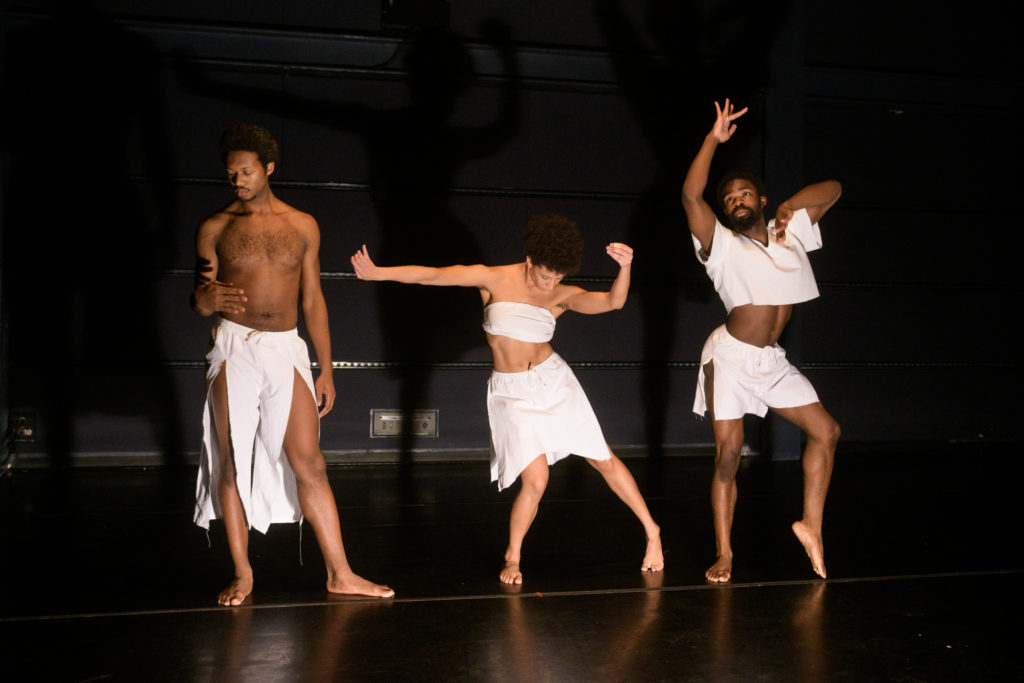

Clear roles emerged over the hour. Bebe was like the center, the mother, the connector—connecting to each of the men and connecting to her dancer self at every moment. Ishmael was the impulsive one, in and out at the same time, expressing his ambivalence in sneaky ways. Ralph was the architect/auteur, contemplating the space, designing the space, turning it into a literary space.

Ishmael, Ralph

I don’t want to say too much about how they interacted, or how they let words slip into their nestlings and challengings, or how they let a diagonal form and then unform, because I hope you’ll see the video for yourself.

What was the genesis of this occasion? Tara asked Ishmael what he would want to do, and he replied that he’d never gotten to dance with Bebe and Ralph. This seems like a modest proposal. But when you think of “Parallels” at Danspace in New York City in 1982, the landmark series of performances that Ishmael curated to challenge the reigning definition of “black dance,” it’s in that vein. “Parallels” was reprised for a tour to Europe in 1987 (which Bebe, Ralph, and Ishmael were part of), and back at Danspace, expanded by a younger generation, in 2012. Here we are in 2020, casting a loving eye on how these three “Parallels” artists have evolved, and how they are existing, existentially, now in their 60s (greater integration of mind and body) and how they intersect as performers.

Ralph downstage, choosing a record to put on the turntable

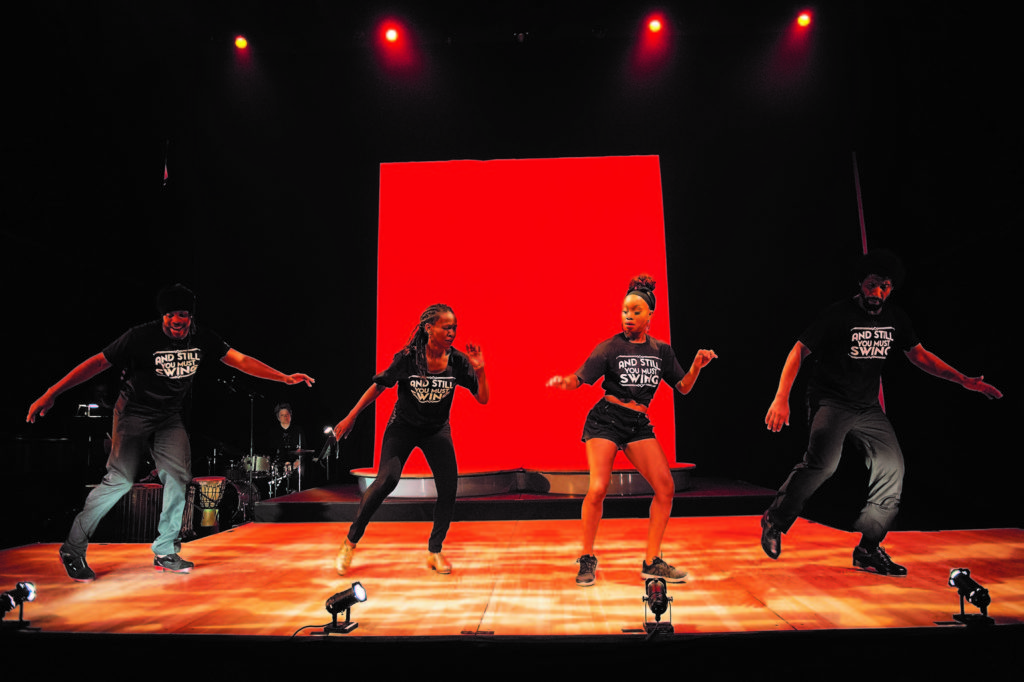

Although this threesome was called together pointedly as a group of Black dance artists, there was something porous about Relations. Maybe because of their familiarity with each other, we were allowed to see/feel their humanity in poetic, edgy, and witty ways.

I enjoyed the after-talk too. I especially appreciated that Ishmael mentioned those we have lost since the 1982 Parallels. It happens that two of those original artists—Harry Sheppard and Blondell Cummings—were good friends of mine. They had already been dancing downtown for a decade, paving the way for Ishmael to make the breakthrough.

The after-talk

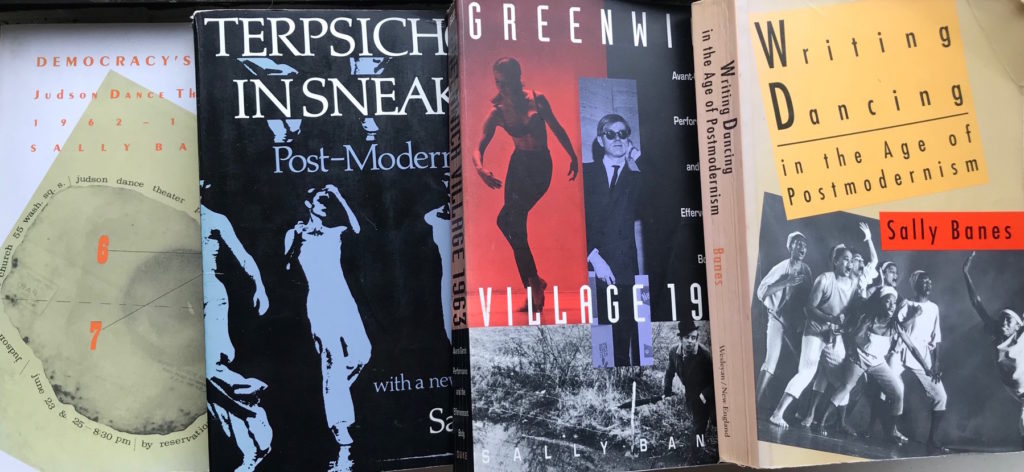

Someone was quoted as saying Relations was like a “Black Grand Union.” Oh good, I didn’t want to be the first to say it! For those of you who don’t know, Grand Union was the legendary, post-Judson, mostly white, improvisation group from 1970 to ’76. I am sure that Ralph, Bebe, and Ishmael weren’t thinking of GU, but I saw some common ground: an anchoring in movement exploration, a certain nuzzling comfort (Grand Union was an unattributed laboratory of Contact Improvisation), patience in allowing things to develop in their own time, being totally themselves yet listening to the others. Being able to surprise each other, goad each other, add a touch of humor or echo to each other.

Naturally I would see them with this lens of Grand Union. For three years, I’ve been immersed in writing a book on this group that will be out in September. I thought of GU as a fluke, only possible because of a specific time and place, unrepeatable. And it was. And this event, Relations, is also unrepeatable. But . . . I hope they repeat it in NYC some day.

(Adjunct materials for Relations—program notes, Tara’s blog, clips of the after talk, and a booklet of their writings—are here.)

Featured 1

One of the most exciting periods of the Merce Cunningham Dance Company was the late sixties and early seventies. Cunningham himself was still dancing magnificently. Composer/philosopher John Cage was still driving the Volkswagen mini-bus on tour. And the company was making and performing some of the most iconic works of contemporary dance.

One of the most exciting periods of the Merce Cunningham Dance Company was the late sixties and early seventies. Cunningham himself was still dancing magnificently. Composer/philosopher John Cage was still driving the Volkswagen mini-bus on tour. And the company was making and performing some of the most iconic works of contemporary dance.

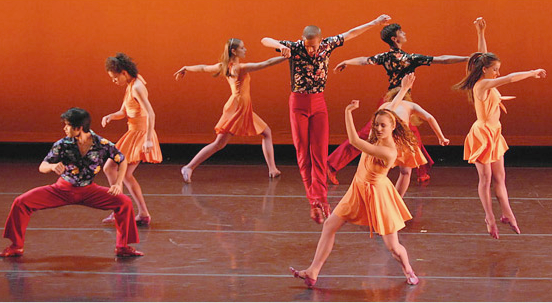

Ephraim Sykes as David Ruffin in Ain’t Too Proud: The Life and Times of the Temptations. The hyper-energized Sykes dove into sensational extremes; he’d bound straight in the air and slam back down into a sliding split. Sheer, adrenaline-fueled, shakin’-down-the mic wildness.

Ephraim Sykes as David Ruffin in Ain’t Too Proud: The Life and Times of the Temptations. The hyper-energized Sykes dove into sensational extremes; he’d bound straight in the air and slam back down into a sliding split. Sheer, adrenaline-fueled, shakin’-down-the mic wildness. Urban Glamour

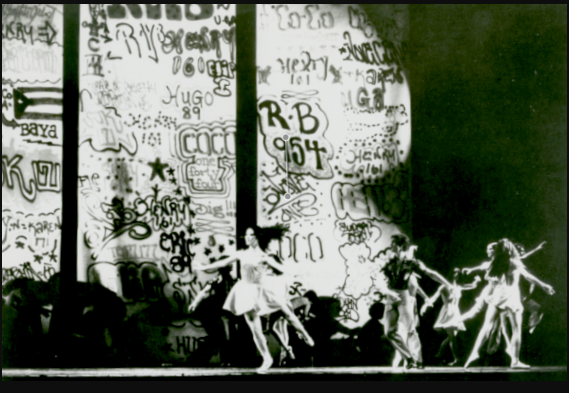

Urban Glamour Anguish in the Bones

Anguish in the Bones

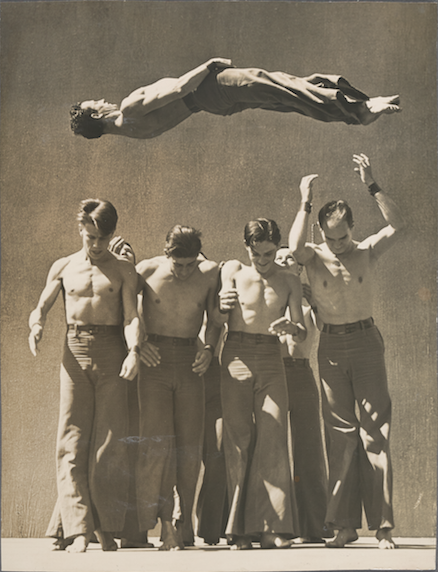

Ted Shawn: His Life, Writings, and Dances

Ted Shawn: His Life, Writings, and Dances

Jerome Robbins, by Himself

Jerome Robbins, by Himself A Body in the O: Performances and Stories

A Body in the O: Performances and Stories Ray Bolger: More Than a Scarecrow

Ray Bolger: More Than a Scarecrow Dancing with Merce Cunningham

Dancing with Merce Cunningham And while we’re on the subject of Merce…

And while we’re on the subject of Merce… How to Land: Finding Ground in an Unstable World

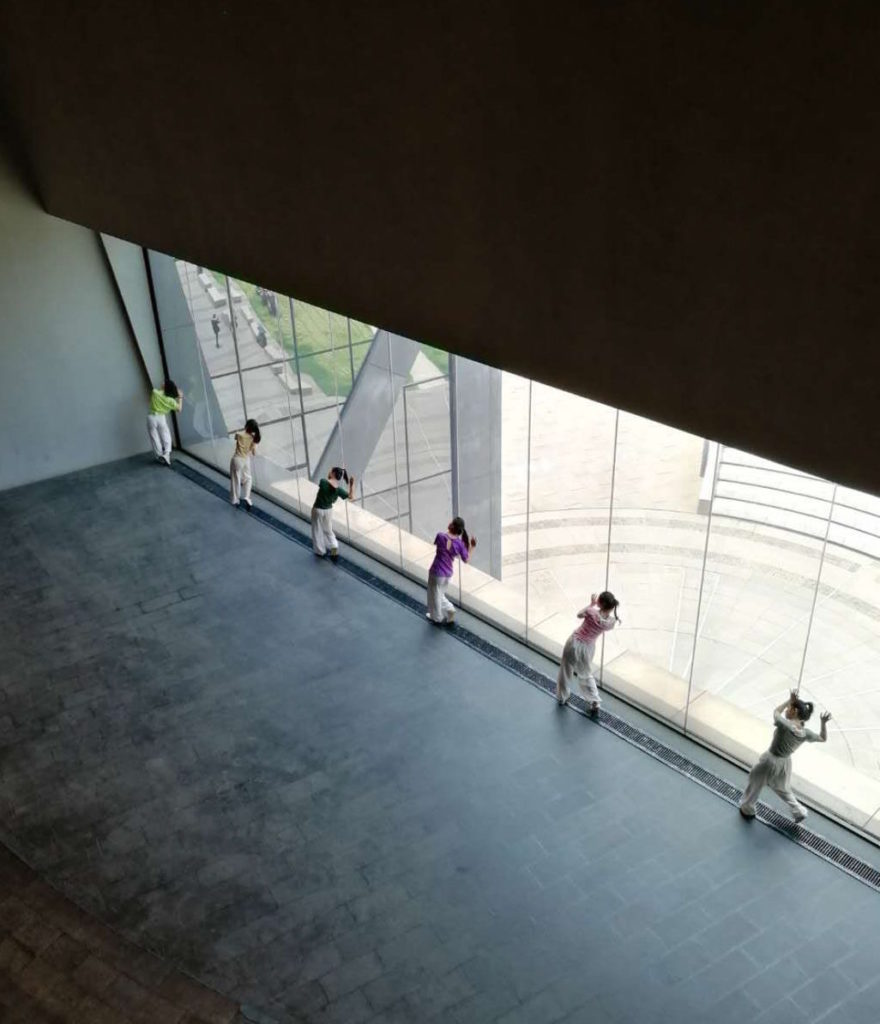

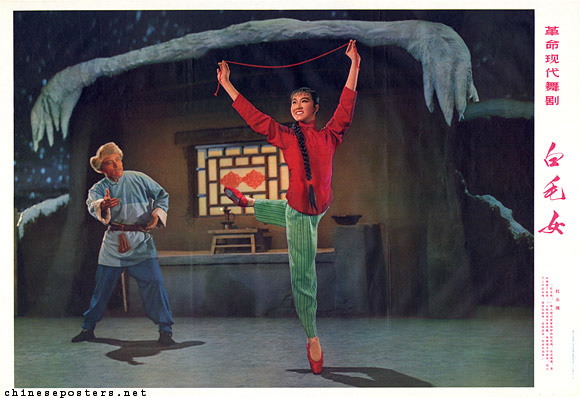

How to Land: Finding Ground in an Unstable World Revolutionary Bodies: Chinese Dance and the Socialist Legacy

Revolutionary Bodies: Chinese Dance and the Socialist Legacy Broadway, Balanchine & Beyond: A Memoir

Broadway, Balanchine & Beyond: A Memoir Keep It Moving: Lessons for the Rest of Your Life

Keep It Moving: Lessons for the Rest of Your Life Glory: A Life Among Legends

Glory: A Life Among Legends Marius Petipa, The Emperor’s Ballet Master

Marius Petipa, The Emperor’s Ballet Master