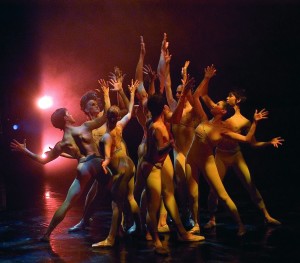

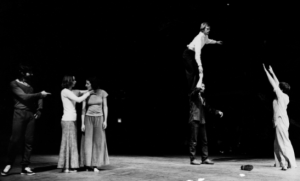

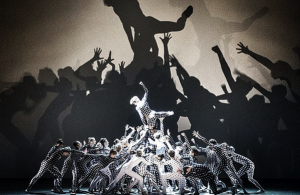

Sometimes it takes an outsider to break through to a new mode, a different look. When 40 NYCB dancers fled across the Koch Theater stage in unmanageable hordes, one knew right away that this was a different kind of ballet. To the music of Woodkid, and wearing variously dotted unitards, the dancers created tableaux that cast huge, heroic shadows on the backdrop (lighting by Mark Stanley). Spartacus for today.

Les Bosquets

JR’s installation last season, using NYCB dancers to form a huge eye, photo by me

This pièce d’occasion, Les Bosquets, was created by French street artist JR, who had wowed us last season with a design on the mezzanine floor that showed an uncanny choreographic sense. His stroke of genius attracted a younger audience, and Peter Martins invited him back to create an eight-minute dance for the week of 21st-century programs.

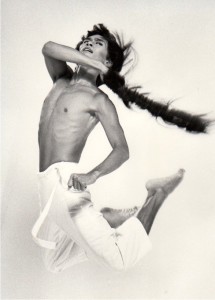

A lot happened in those eight minutes. The theme of a prince trying to reach his ideal woman amidst a forest of obstacles was familiar from classic ballets like Sleeping Beauty, Swan Lake, and Firebird. But here, the prince was jookin dancer Lil Buck, which made an aesthetic/cultural point. Since both Lil Buck and the ballerina, Lauren Lovette, were dressed in papery white, they seem destined to be together. And yet they never came together—except in live, ultra close-up film. As in Romeo and Juliet, everything aligned to keep them apart, even a line of other dancers. (if you want to see a duet between a street dancer and a ballet dancer where they really do dance together, check out this wonderful behind-the-scenes video of William Wingfield and Whitney Jensen.)

Les Bosquets with Lil Buck and Lauren Lovetter, photo by Paul Kolnik

In the end, when they all lined up for a bow, one could see that the thousands of dots, spread over the costumes of the 40 dancers, formed a pair of eyes—an echo of the collectively made eye that JR created last season. Les Bosquets has been dismissed as a novelty or a crowd-pleaser, but I found it tantalizing. It made me wonder what JR would do with a longer span of time.

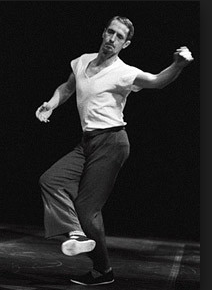

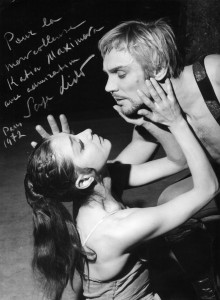

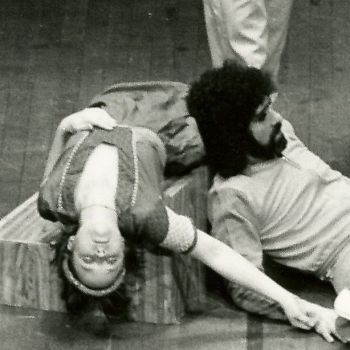

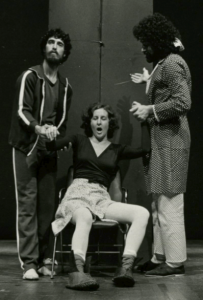

Barber Violin Concerto with Charles Askegard, Megan Fairchild, Sara Mearns, and Jared Angle, photo by Paul Kolnik

Apparently Peter Martins helped translate JR’s ideas into steps, and it’s interesting that this collaboration was on the same program with Barber Violin Concerto, which was a past foray of Martins into new territory. He originally made it in 1988 for two NYCB dancers and two Paul Taylor dancers—Kate Johnson and David Parsons. Megan Fairchild’s rambunctious jittery energy in the Kate Johnson role was as far from Martins’ comfort zone as Lil Buck was.

In the context of NYCB’s Balanchine and Robbins rep, Forsythe’s Herman Schmerman Pas de Deux (1992) is a breakthrough too. The movement is rangier, quirkier, and the walking—this may seem like a small thing—is done heel-first. How often you see ballet dancers walk like a normal human on the stage? They are trained to walk toe first, which I have always felt was unnatural. I loved the way Amar Ramasar, with his broad hunky shoulders, shifted deliciously as he took those insolent Forsythian heel-first walks.

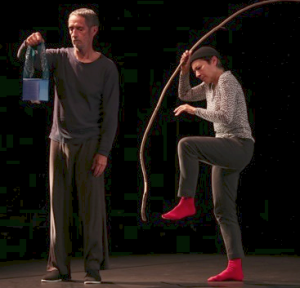

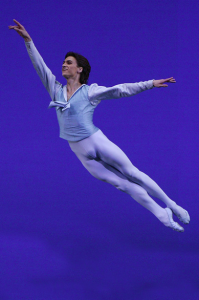

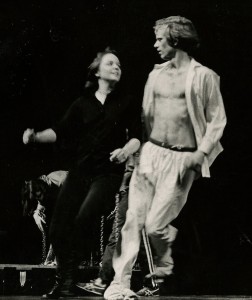

Wendy Whelan and Tyler Angle in This Bitter Earth, photo by Paul Kolnik

My last comment about this program: In her comeback after a sabbatical and hip surgery, Wendy Whelan performed Wheeldon’s This Bitter Earth (excerpt) with Tyler Angle, gliding through the piece with a calm force—or a forceful calm. But actually Whelan’s’ presence hovered over the evening. For years she was the go-to girl for Herman Schmerman and she had created a lead role in Ratmansky’s Namouna (the whole second part of the program). But more than that, her ability to imbue contemporary ballet with crystal-edged clarity and a completely unsentimental kind of spirituality makes her the ideal interpreter of 21st-century choreographers. Which is why it will be sad that she will give her farewell to NYCB this October.

Featured Uncategorized 1