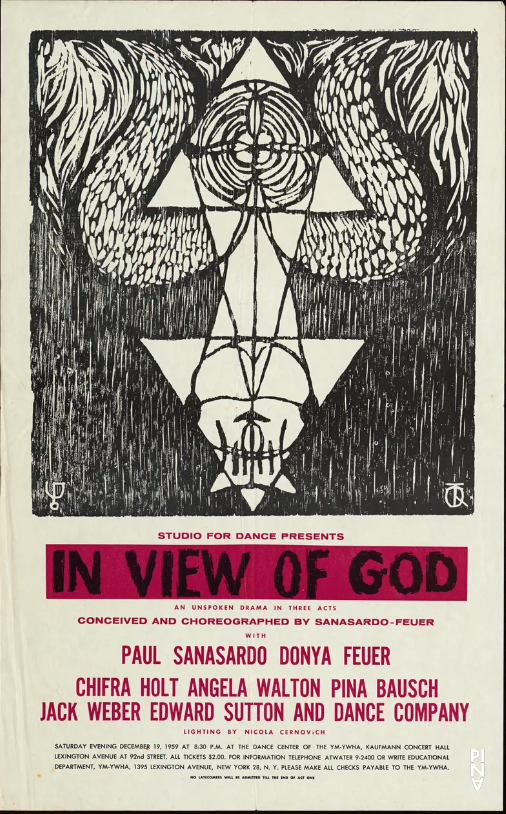

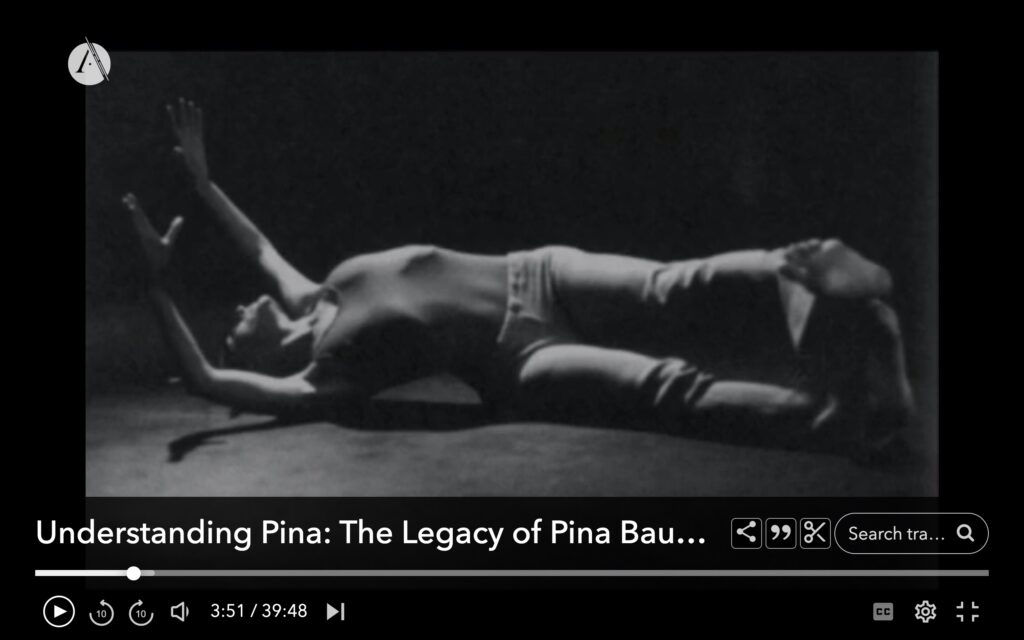

The legendary 1966 series 9 Evenings: Theatre & Engineering involved nine interdisciplinary artists. When a 2024 exhibit at the Getty looked back at this landmark event, curator Nancy Perloff invited me to write about the four dance artists who contributed. (Also in that series were John Cage, Robert Rauschenberg, Alex Hay, Robert Whitman, David Tudor, and Öyvind Fahlström.) This text is reproduced from the exhibition catalog Sensing the Future: Experiments in Art and Technology (E.A.T.), edited by Nancy Perloff and Michelle Kuo © 2024 J. Paul Getty Trust.

“Looking back at 9 Evenings allows a glimpse of the wild imagination that fueled a burgeoning alternative to conventional concert dance.”

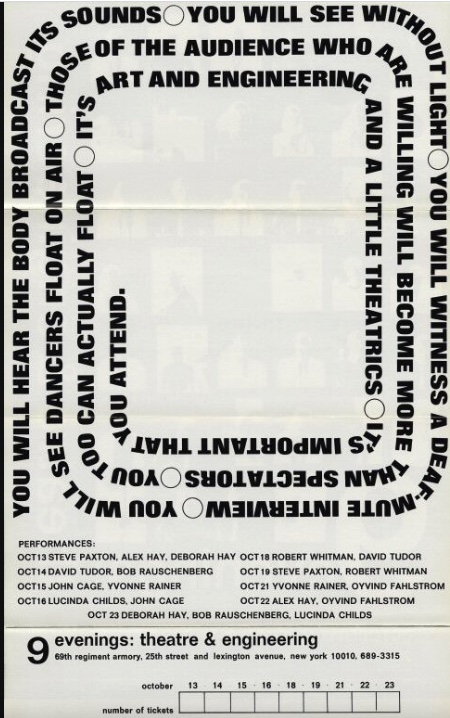

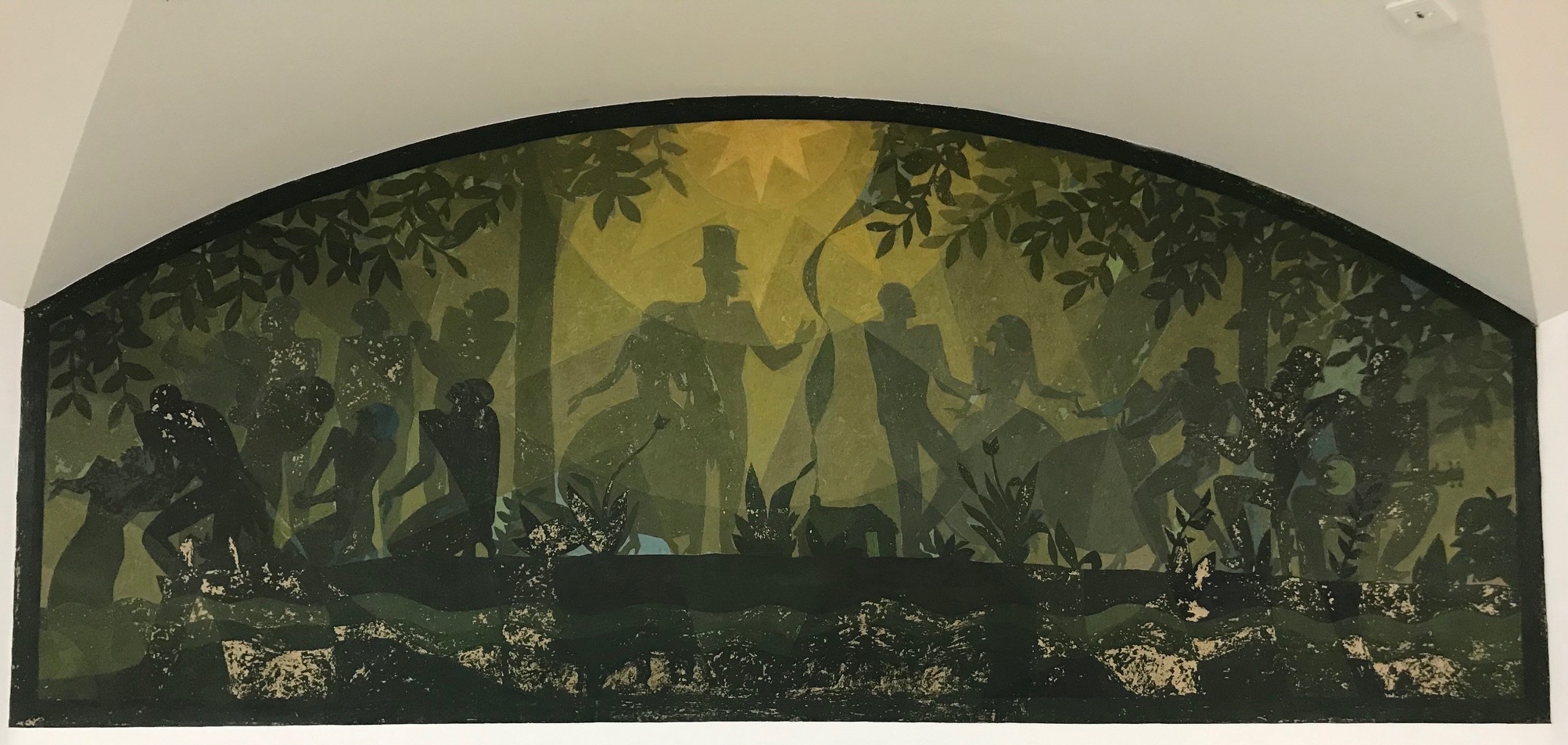

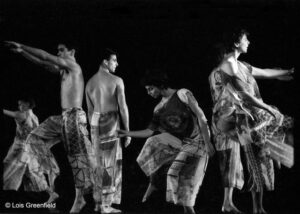

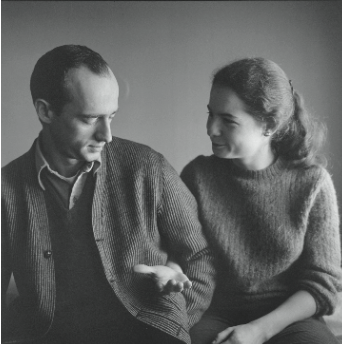

When given the opportunity to work with engineers from Bell Telephone Laboratories, four dance artists—Steve Paxton, Yvonne Rainer, Lucinda Childs, and Deborah Hay—welcomed the chance. They were all living in or near SoHo, the New York City neighborhood where artists of different disciplines were blurring genre boundaries in a spirit of collaboration. Billy Klüver, the physicist and engineer who helped instigate 9 Evenings: Theatre & Engineering, told the artists to ask for anything they wanted—or could imagine—and that his team of engineers would try to invent what didn’t yet exist. The final series, with ten artists’ works (each one performed twice), took place at the massive 69th Regiment Armory in New York in October 1966.

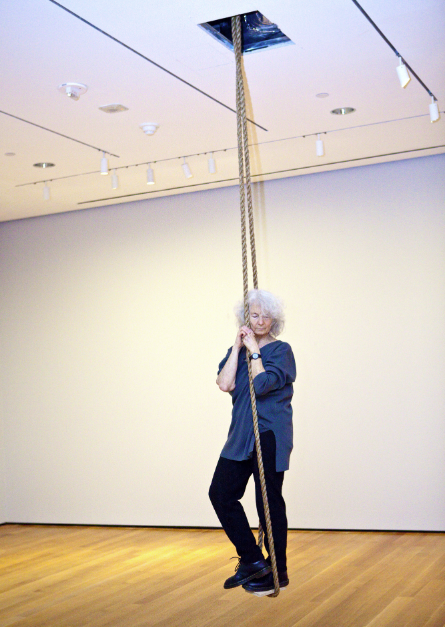

Each of the dance artists had a different fantasy about what would be possible. But there was one wish they all seemed to share. Julie Martin, director of Experiments in Art and Technology (E.A.T.), recalled, with only slight exaggeration, that when Klüver asked the artists to state their desires, “Everybody wanted to float.”[1]

The Influence of John Cage, Robert Dunn, and Simone Forti

It’s true that all four dance pieces had a component that defied gravity. But it’s also true that they stayed grounded, task-like, insistently mundane. These four dance artists valued the ordinary realm that Robert Dunn had encouraged a few years earlier. A disciple of John Cage, Dunn taught a composition class at Merce Cunningham’s studio from 1960 to 1962, breaking open the possibilities of what a dance could be. As Rainer said recently, Cage “was constantly broadening what was acceptable as art.”[2] Embracing the ordinary was a way to pay attention to what was present, what was real, to notice the life around you.

Like Cage, Dunn was deeply influenced by Zen Buddhism; he fostered an environment where the students felt free to experiment, unjudged. Paxton, Rainer, Childs, and Hay were all part of that class, and visual artists like Robert Rauschenberg and Robert Morris often visited the sessions. The ensuing explosion of activity led to the groundbreaking collective Judson Dance Theater, so named because the place that welcomed this band of renegades was Judson Memorial Church in Greenwich Village.

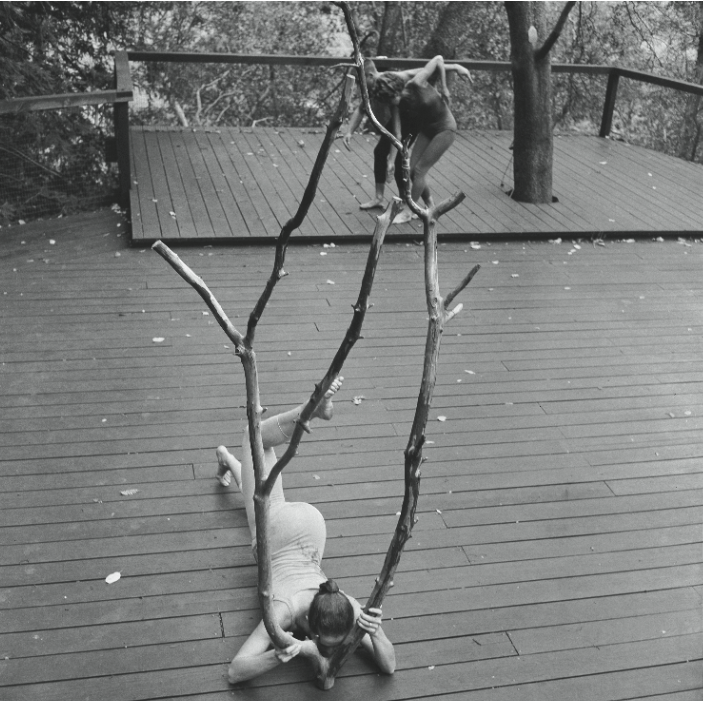

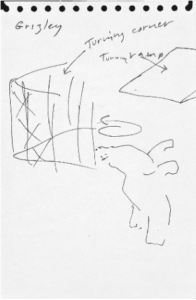

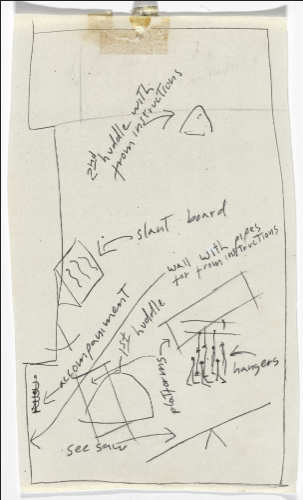

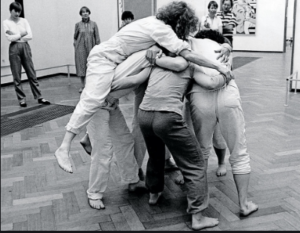

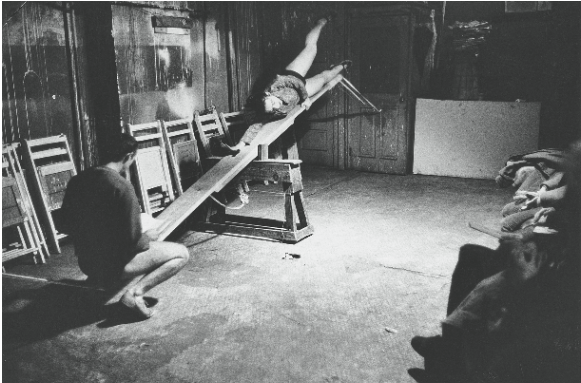

Simone Forti was also in that class. After about five years of improvising with Anna Halprin in California, she was familiar with the practice of making dances based on scores, lean structures to be fleshed out by the performers in their own ways. It was the encounter between Halprin’s approach to tasks in natural settings on the West Coast and the more structured approach of Dunn that led Forti to create Dance Constructions in 1961.[3] In these short works, Forti paired motion and object such that each was necessary to the other. For example, Slant Board (1961) conjoined an object—a 45-degree angled wooden surface with ropes attached—with the performers’ task of traversing that steeply sloping surface while holding the ropes to keep from falling. Neither the construction nor the task made sense without the other. Forti considered these pieces to be both dance and sculpture.

Dance Constructions can be seen as a precursor to 9 Evenings, which could almost have been called Advanced Dance Constructions or Dance Constructions’ Leap into Science Fiction. Although Forti was not one of the four dance artists “commissioned”[4] for the Armory event, she was in some ways a presiding spirit. Rainer and Paxton had performed in her Dance Constructions, which had opened up new ways of exploring the physicality of motion.[5] For the Armory event, Forti, who was married to performance/theater/media artist Robert Whitman at the time, became the person responsible for keeping track of the meetings and writing reports.

Forti’s observation that 9 Evenings was more of a way station than a point of arrival is well taken. None of the dance pieces was a finished, repeatable product. There was never a dress rehearsal that integrated the technology with the choreography. Further, no one was trying to make a work that was recognizable as art. As Paxton said while describing Marcel Duchamp’s influence, “It was almost that our art of those times was anything that did not look like any art that had happened.”[6] (I don’t think it was lost on Paxton or anyone else that Duchamp shattered existing notions of art at the same armory in 1913.)

Cage’s concept of the permeability of art and life infused these works, and along with that came a certain acceptance of messiness. Forti described it to me in terms of the changing goals of literature: “In fiction there’s probably less interest in a story that gets wrapped up in the end with some kind of punchline. [There was] a leaning toward having things open. . . . It was kind of a philosophical need John Cage filled.”[7] Forti wrote during the planning process: “I’m beginning to feel that the main function of the performances is not so much the presentation of art pieces, but a step towards the creation of a situation that will later be important to the making of art.”[8]

Cage and Dunn embraced the Bauhaus idea of using available materials. If you have copper handy, you use copper, not gold. If you have paper clips handy, you make a necklace out of them and do not wait for diamonds. For the Armory project, there was a shift away from this idea to dreaming bigger and imagining the possibilities of new technologies, even though there were bound to be “techno-hiccups” along the way.

Influence does not always involve a direct connection. As Forti speculated, groundwork for the future was being laid. Stephan Koplowitz, the longtime explorer of site-specific work and author of On Site: Methods for Site-Specific Performance Creation (2022), was a student at Wesleyan University in the late 1970s. In a recent conversation, he recalled the excitement he felt when learning about 9 Evenings: “When I read about 9 Evenings at Wesleyan, it blew my mind. It was the Holy Grail. It made me wonder, What is possible? How can we combine technology and the body and still keep our humanity? Technology and human bodies are blurring now. 9 Evenings was the beginning of that.”[9]

All four dance artists, plus Forti, sustained long international careers almost entirely outside the proscenium stage. Looking back at 9 Evenings allows a glimpse of the wild imagination that fueled a burgeoning alternative to conventional concert dance.

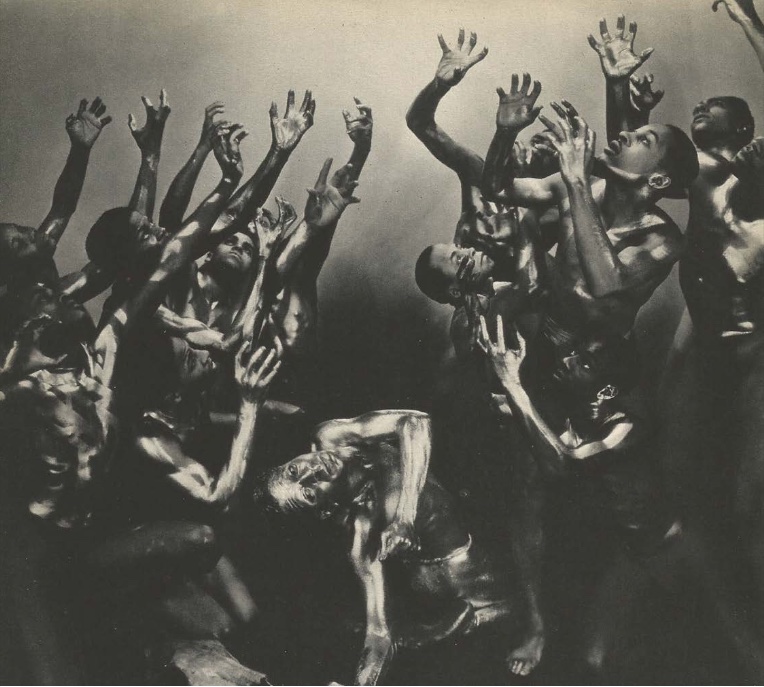

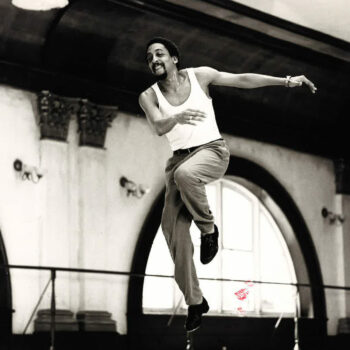

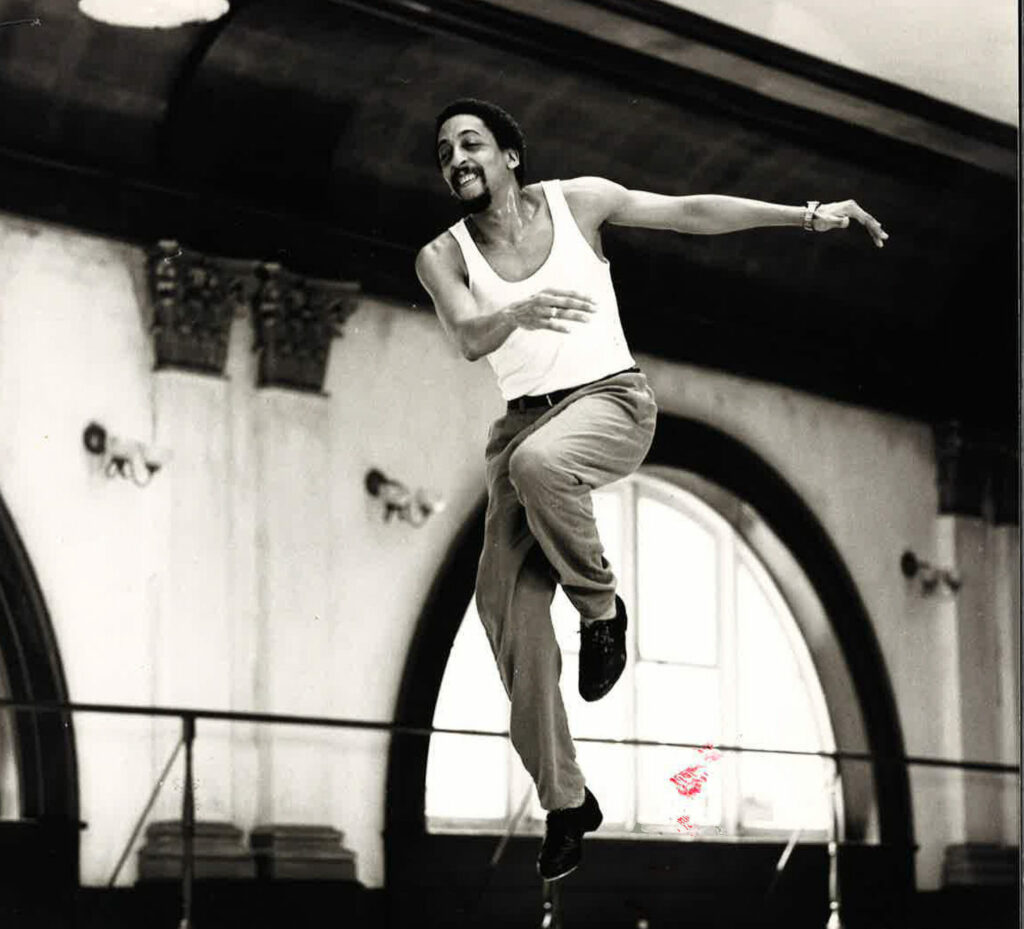

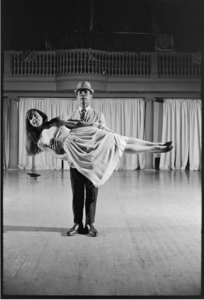

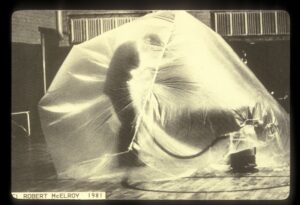

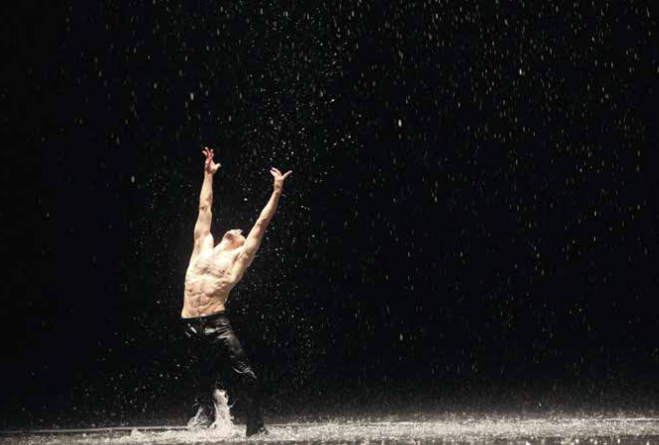

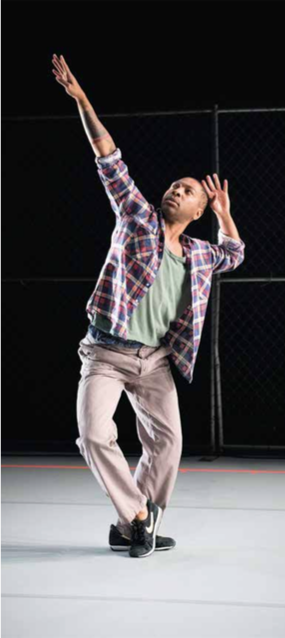

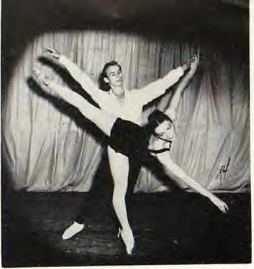

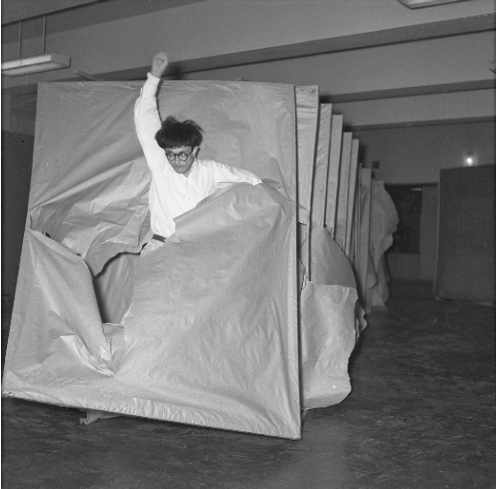

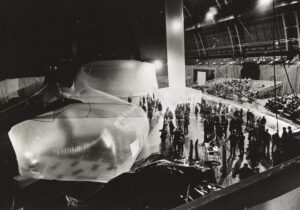

Steve Paxton’s Physical Things

For Physical Things, Paxton used clear polyethylene sheets to build a gigantic maze that the critic Lucy Lippard called “a series of billowing tunnels” attached to a hundred-foot-tall tower.[10] “I was drawn to the inflatability of the material,” Paxton wrote, “and that you could make shapes with it and change your perception of the space.”[11] Paxton had been experimenting with plastic inflatables since 1963. On 29 January of that year, he performed Word Words, a collaborative duet with Rainer, in silence, at Judson Memorial Church. The next night he created Music for Word Words, which he conceived as accompaniment for the duet the night before. He started Music for Word Words standing inside a room-sized bubble that had been inflated by an industrial vacuum cleaner. He simply deflated the plastic until it shrank to drape over his body like a rumpled suit. He used polyethylene again for The Deposits (1965), which included an inflated plastic armchair at Kutsher’s Hotel and Country Club in upstate New York that Paxton and Hay batted around with big paddles. Another instance was Earth Interior (1966), for which he created a hundred-foot tunnel with side passages in a skating rink in Washington, D.C.

In Physical Things, audience members had to pass through this structure, and along the way they could perceive other people ahead of them. Seen through the plastic dividers, those figures looked hazy and ungrounded—floating, as if in a fog. Spectators also encountered bizarre sights like limbs of performers that protruded from a dark mound—“highly surrealistic in effect.”[12] As they exited the last “room,” each audience member was given a wireless radio handset so they could hear voices and sounds coming from a layer of sound loops overhead. As they changed locations, they could assemble their own sequence of sounds. In the documentary film,[13] we hear a snippet about the astronaut John Glenn’s trip to outer space, which was uncannily apt.[14]

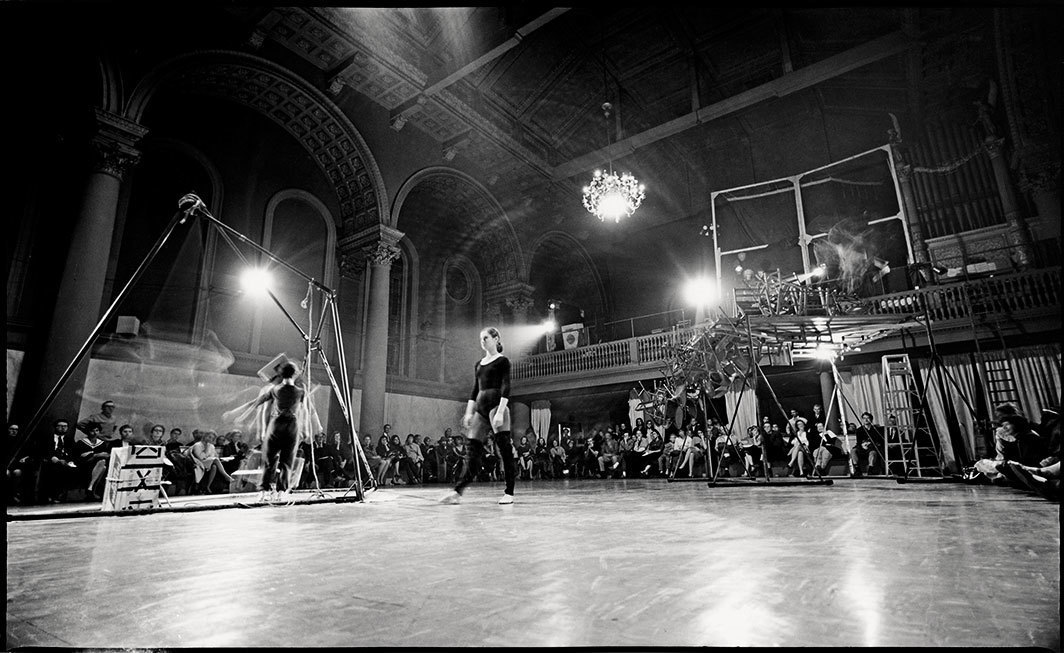

Paxton’s Physical Things; photo by Peter Moore showing an overview of large inflated air structures from the balcony behind the control booth, Getty Research Institute

The Armory was the last site of Paxton’s love affair with polyethylene. The outgassing chemicals hadn’t bothered him before, but by 1966 he had become aware of their toxicity. Noting that hordes of people had passed through his plastic enclosures, he was just a tiny bit rueful on the phone: “It was toxic. They were just subtly poisoned. Sorry, everybody.”[15]

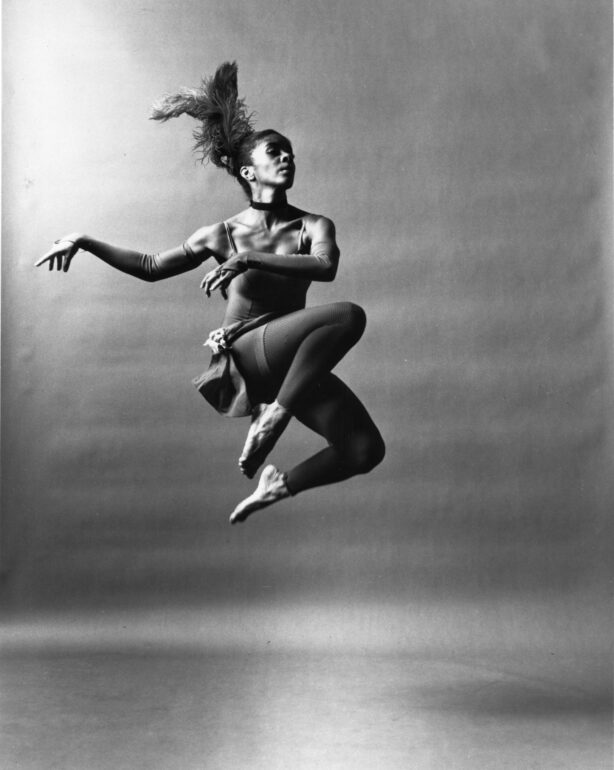

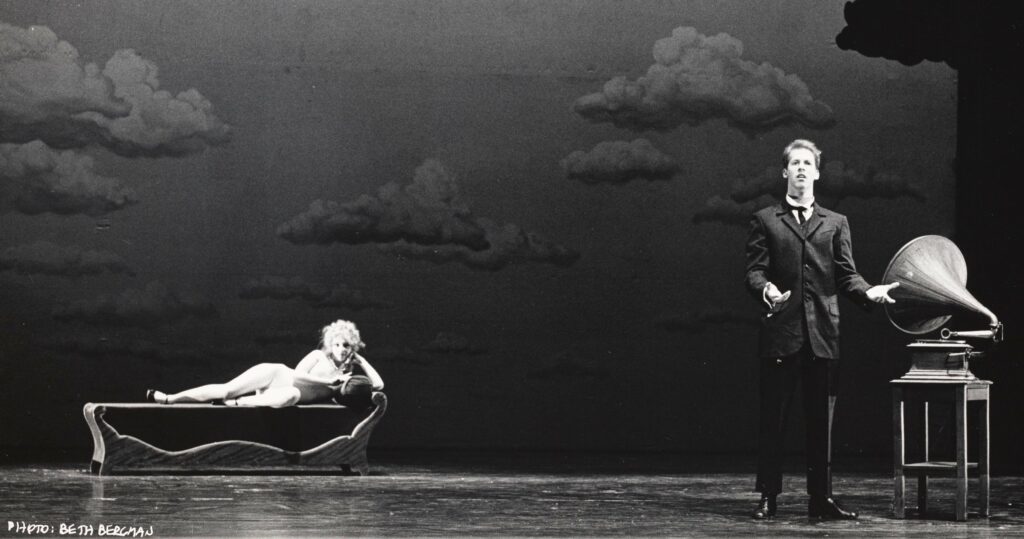

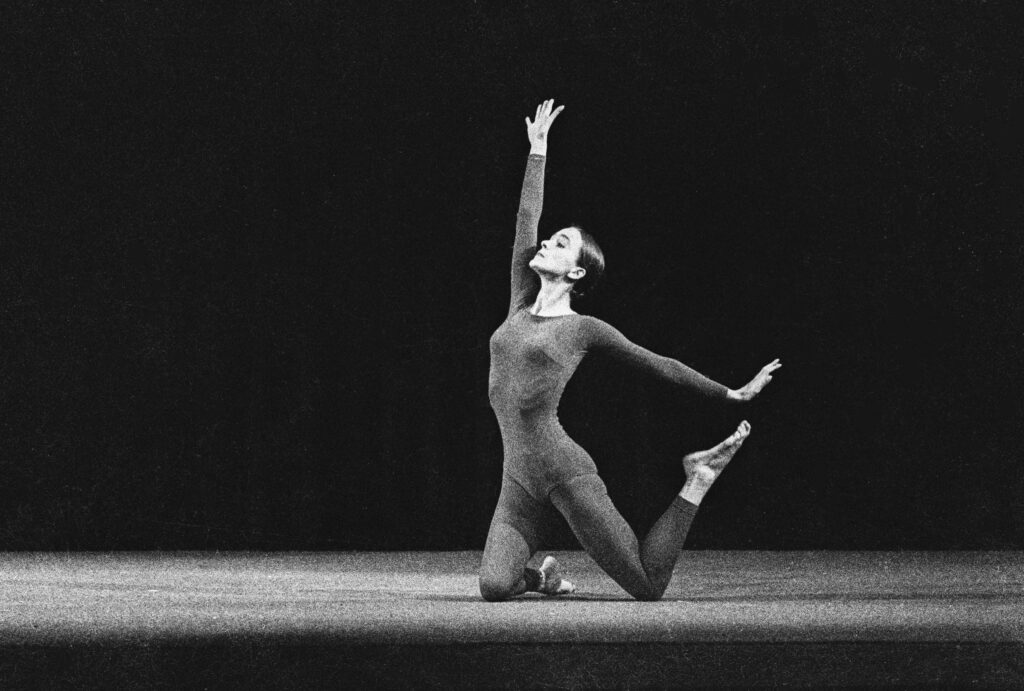

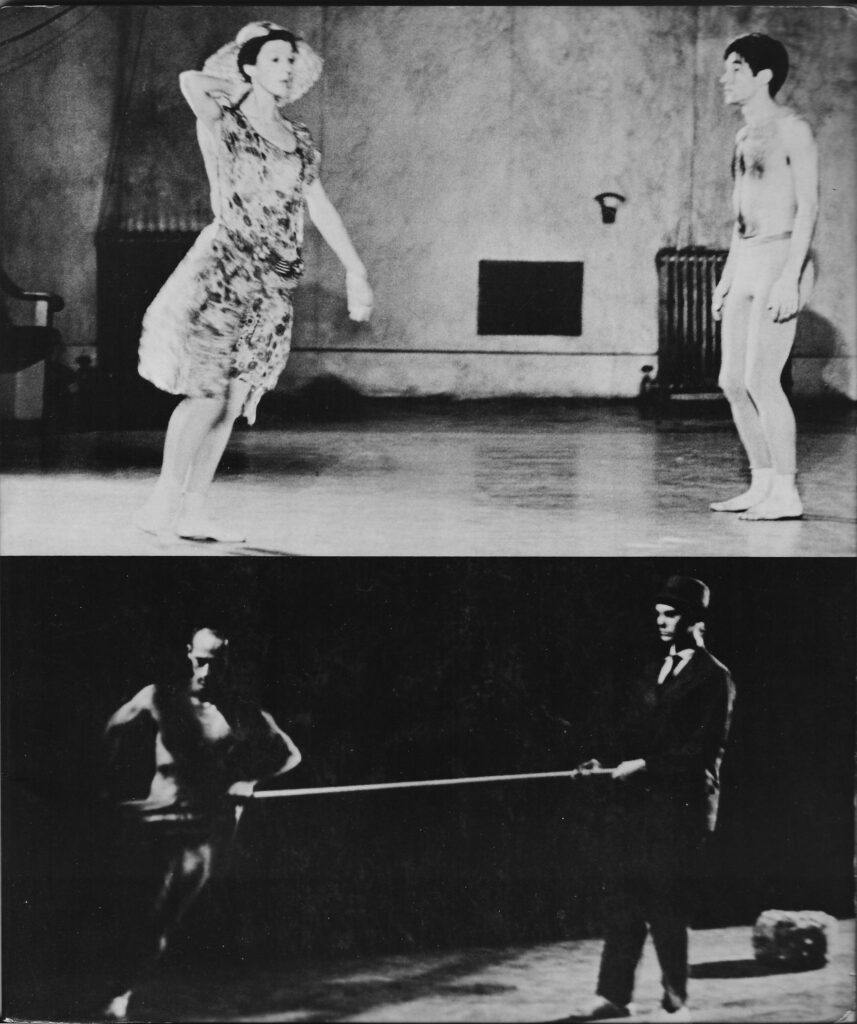

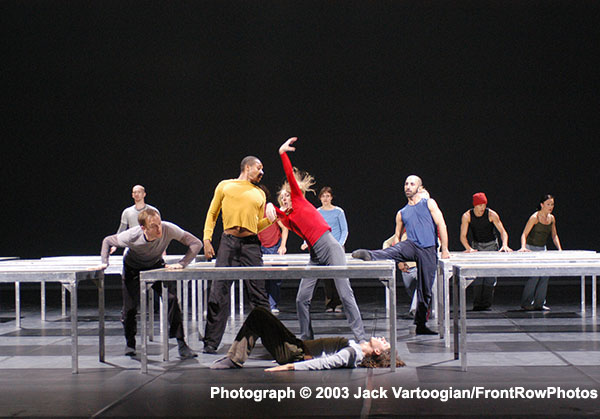

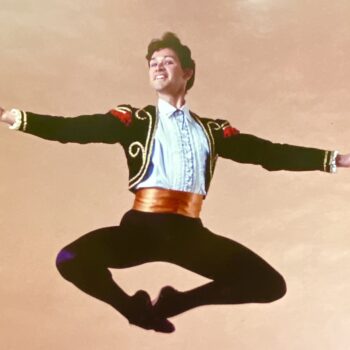

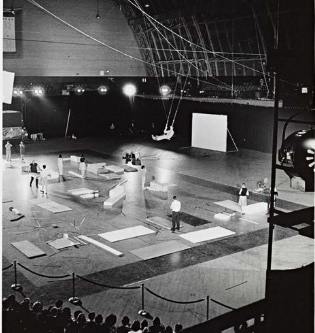

Yvonne Rainer’s Carriage Discreteness

For Rainer, the many tasks and objects in Carriage Discreteness were typical of her work at the time—for instance, the red rubber balls in Terrain (1963), mattresses in Room Service (1963) and Parts of Some Sextets (1965), and various weighted objects like paper and bubble-wrap in The Mind Is a Muscle (1966)—but more elaborate in terms of space and mechanics. She gathered a wide array of differently weighted objects that included—at least in the plan—one hundred wooden slats, one hundred foam slats, six mattresses, five pieces of paper, two elevator weights, and five Styrofoam beams donated by the sculptor Carl Andre (who also performed in the piece).[16]

Rainer split most of the actions into two kinds of events: performers moving objects to specific spots on the floor, and mechanically activated events like movie fragments, slide projections, light changes, closeups on TV monitors, and a small plexiglass globe guided by an elevated pulley across the space—all planned to happen in a prescribed sequence. During the performance, Rainer was sitting high on a balcony, directing the performers to carry an object, one at a time, and place it in one of twenty rectangles marked on the floor. The performers were receiving her messages through a walkie-talkie attached to either a shoulder or a wrist. Perhaps because they were intent on hearing the instructions, they wore a bit of a zombie look. Rainer later regretted her elevated perch. In her autobiography, she wrote that she was “in the remote balcony overlooking the 200 x 200-foot performing area like a sultan surveying his troops on a vast marching field.”[17] She could have given her performers the freedom to make their own choices, which undoubtedly would have made for a livelier performance. “But no,” she wrote, “I had to exercise my controlling directorial hand.”

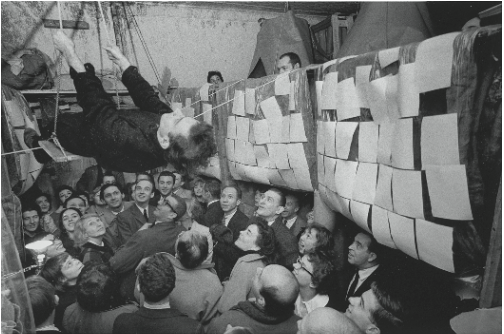

Yvonne Rainer’s Carriage Discreteness, Peter Moore’s photo shows the vast Armory, the objects on the floor, a freestanding screen, and Steve Paxton swinging from the rafters.

(Rainer had another reason for bad memories of this evening. In the wee hours after the first performance, she was struck with a medical disaster that almost killed her. She was rushed to the hospital and operated on immediately. For the second night of Carriage Discreteness, Morris, who was her romantic partner at the time, stepped into her role as “sultan” and things went smoothly. But it took months for Rainer to recuperate from a severe intestinal blockage replete with gangrene and peritonitis.[18])

In 1966, Rainer was soon to migrate from performance to film, and Carriage Discreteness foreshadowed that shift. The film elements included clips of the actors W. C. Fields and James Cagney projected onto a large, freestanding screen and the audiotape of a conversation between a man and a woman about a film. This dialogue, originally between Rainer and Morris, and vocalized by Childs and William Davis, suggests that talking about films can be as seductive as watching a film.

Despite the diffuse quality—and the fact that on the first night the mechanical events had been accidentally programmed backwards (!)—Carriage Discreteness had two spectacular moments. The first was when, in a clip from the film The Old Fashioned Way (1934), Fields is precariously balancing a pile of cigar boxes when a man in his audience throws a ball that topples the boxes. Suddenly, the huge screen in the Armory broke apart and crumbled to the floor in big chunks. What was two-dimensional vaudeville self-destructed in a real, three-dimensional way. Forti remembers it vividly: “Suddenly the parts came apart and it fell down in parts. It was quite beautiful, quite loud, quite surprising.”[19]

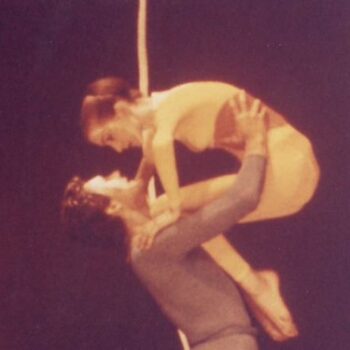

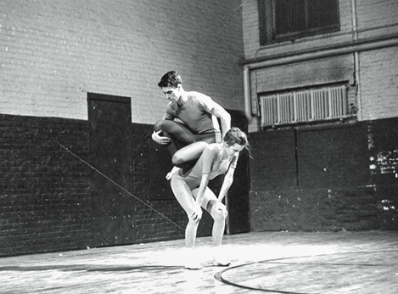

The other highlight of Carriage Discreteness—this is where floating came in—was Paxton sitting on a swing that soared out into the upper reaches of the 120-foot-high Armory. He wasn’t pumping his legs (that was “forbidden,” he said);[20] rather, he just let the action subside after the first big push. For Paxton, it was a stimulating kinetic experience: “The initial swoop of the swing was great, but what was best was that the piece lasted long enough that . . . the swing just died down. It got smaller and smaller and smaller and smaller till I could barely tell I was moving. I was going a little bit forward and a little bit back and no sense of arc at all, and that was incredible. That was like a revelation.”[21]

Fast forward to Rainer’s recent work, Hellzapoppin’: What about the Bees (2022), in which the performance area was also split into two parts, with dancers on stage right and film projections on stage left. When reminded of this congruence with Carriage Discreteness, Rainer said, “I guess I’m interested in a field of activity where you can’t take it all in, you have to choose where you focus your attention.”[22]

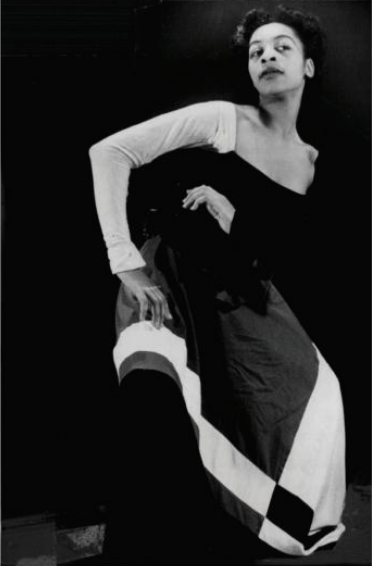

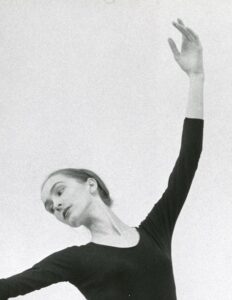

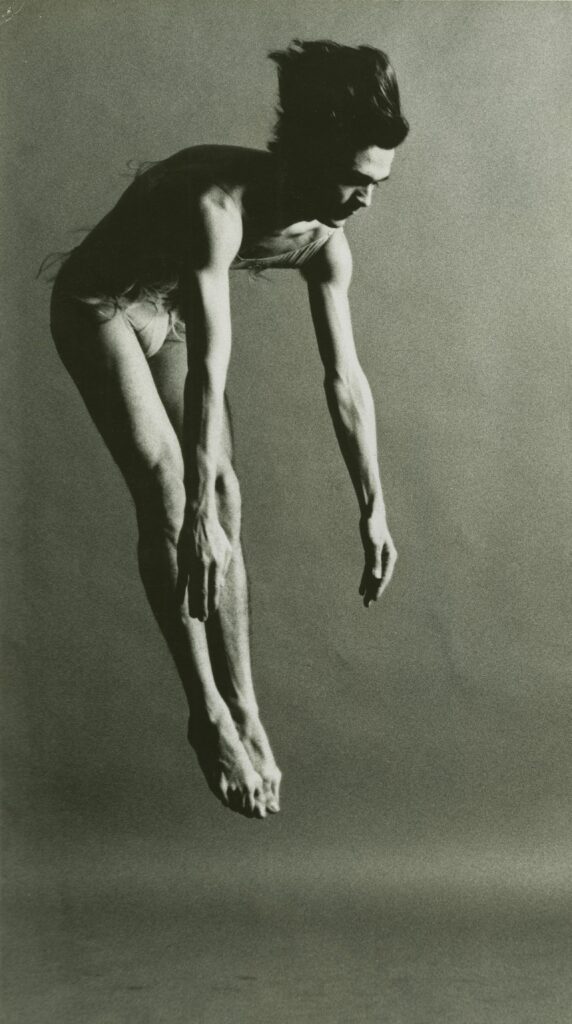

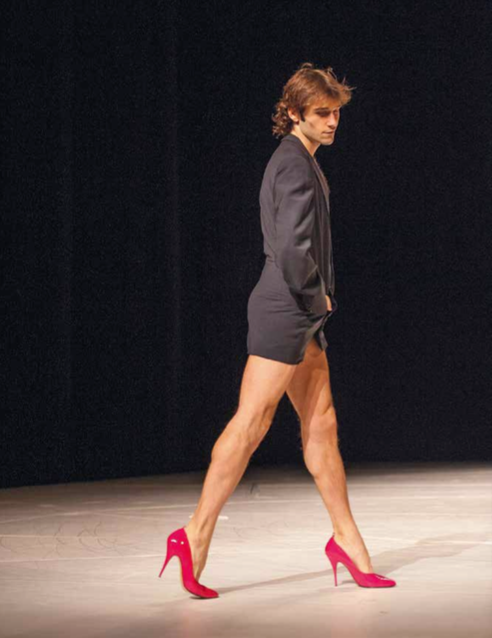

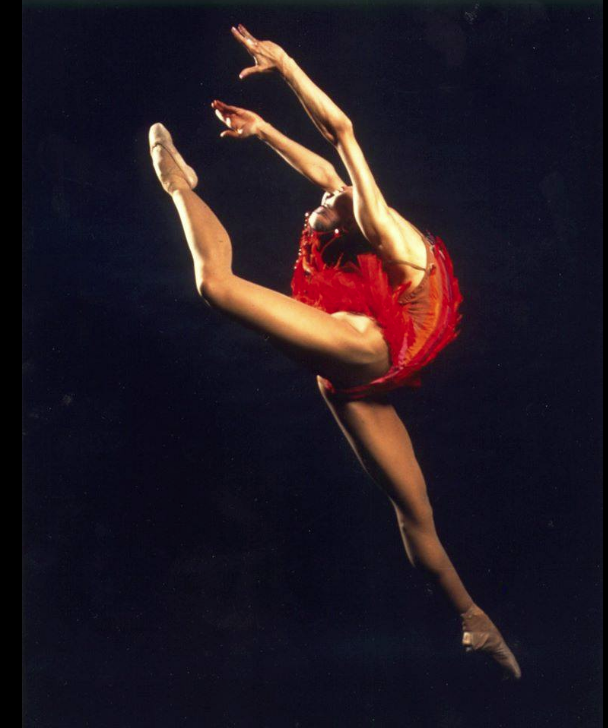

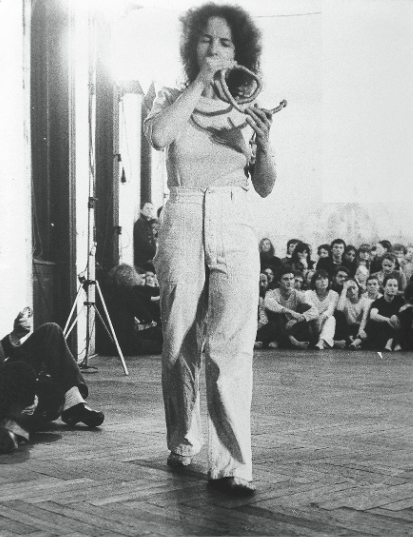

Lucinda Childs’s Vehicle

Childs, who had given a brilliant, absurdist cast to choreographing with objects (for instance, in her 1964 solo Carnation, she manipulated sponges and other domestic objects to hilarious effect), knew from the beginning that she wanted to experiment with the Doppler sonar device. To elicit sound from the invisible sonar beam, Childs stood among three hanging, sand-filled buckets, guiding them in circular motion. (These red buckets were part of the sprinkler system required of every SoHo loft. As Childs quipped, they were “stolen from the fire department.”[23]) Hanging at just the right level to be intercepted by the sonar beam, the buckets created a sound that Klüver called “a swishing noise like wind blowing through a forest.”[24]

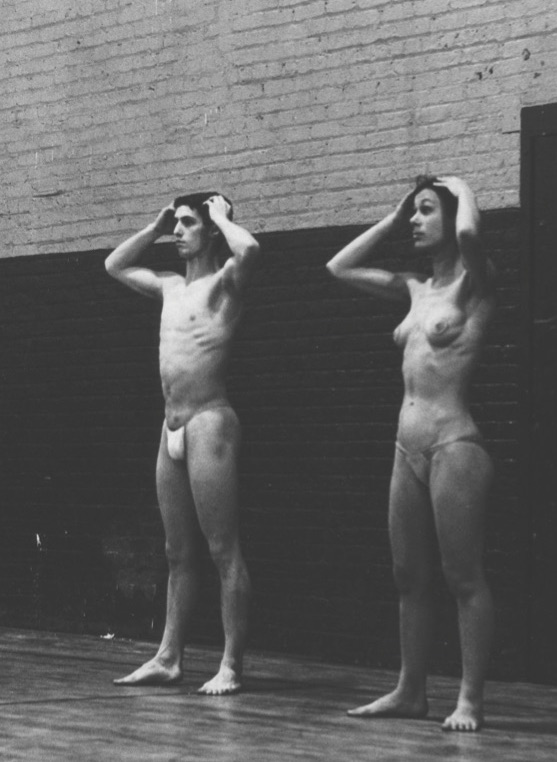

Lucinda Childs’ Vehicle, Peter Moore photo showing William Davis and Alex Hay, left, inside plexiglass enclosure, Childs at right with buckets, Getty Research Institute

The piece began with a floating plexiglass cube, airborne via old-fashioned methods: suspended from a scaffold and rotated by the currents of an electric fan. This cube bobbed in the air, with a lightbulb inside it, at about eye level. A larger, phonebooth-sized plexiglass enclosure, with Alex Hay inside, was air-cushioned from below with what Klüver called a “ground-effects machine.”[25] It didn’t work quite the way they had planned, so William Davis (a dancer with Cunningham’s company) helped steer it in order to deliver the three red buckets to Childs. To extend the action outward, the sound from the sonar beam was amplified by twenty speakers, and images and shadows of the objects were projected onto three screens.[26]

Childs was happy with at least two of the components: the variety of sounds elicited by the swinging buckets and the oscilloscope that projected the image of the sounds onto one of the screens.[27] However, the process of trying to put it all together in her loft was “frightening because nothing really totally came together until the time of the performance.”[28]

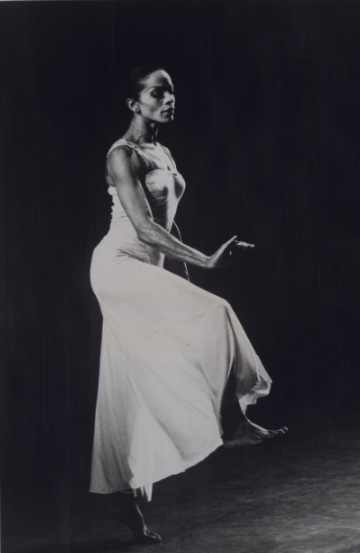

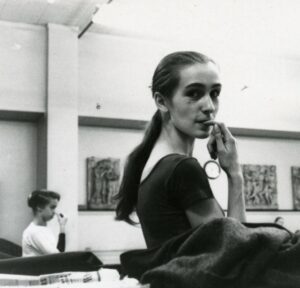

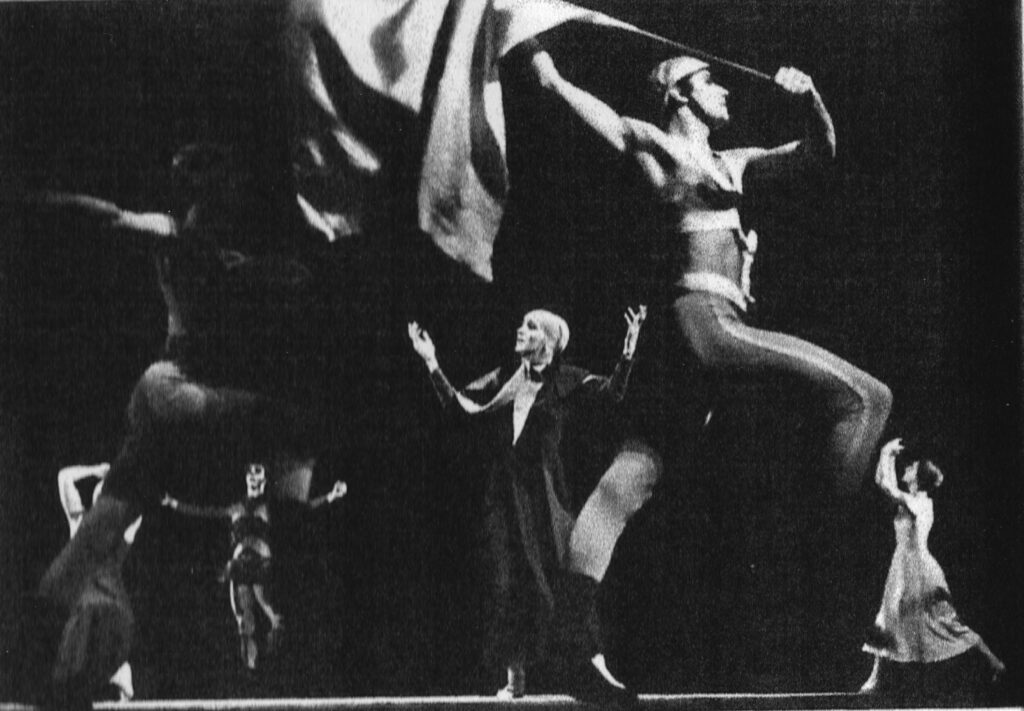

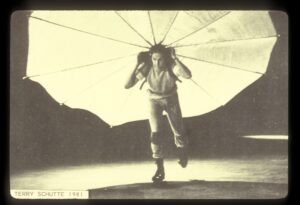

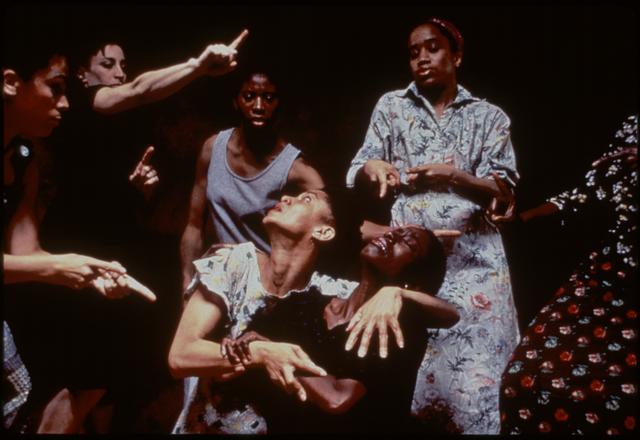

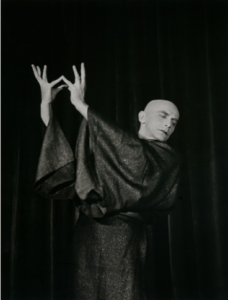

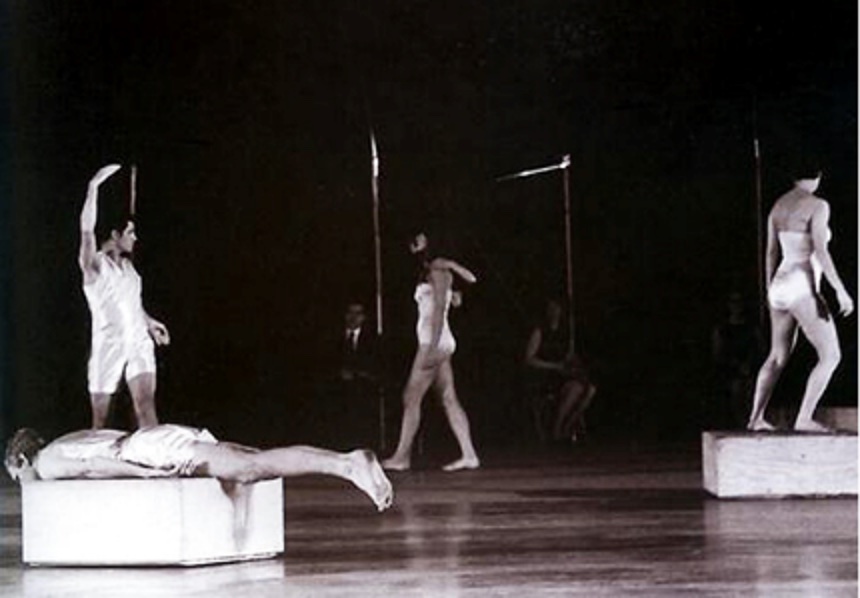

Deborah Hay’s solo

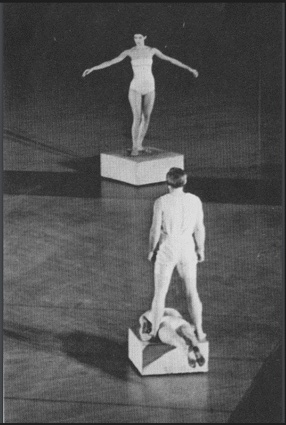

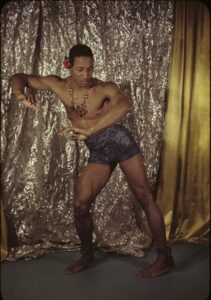

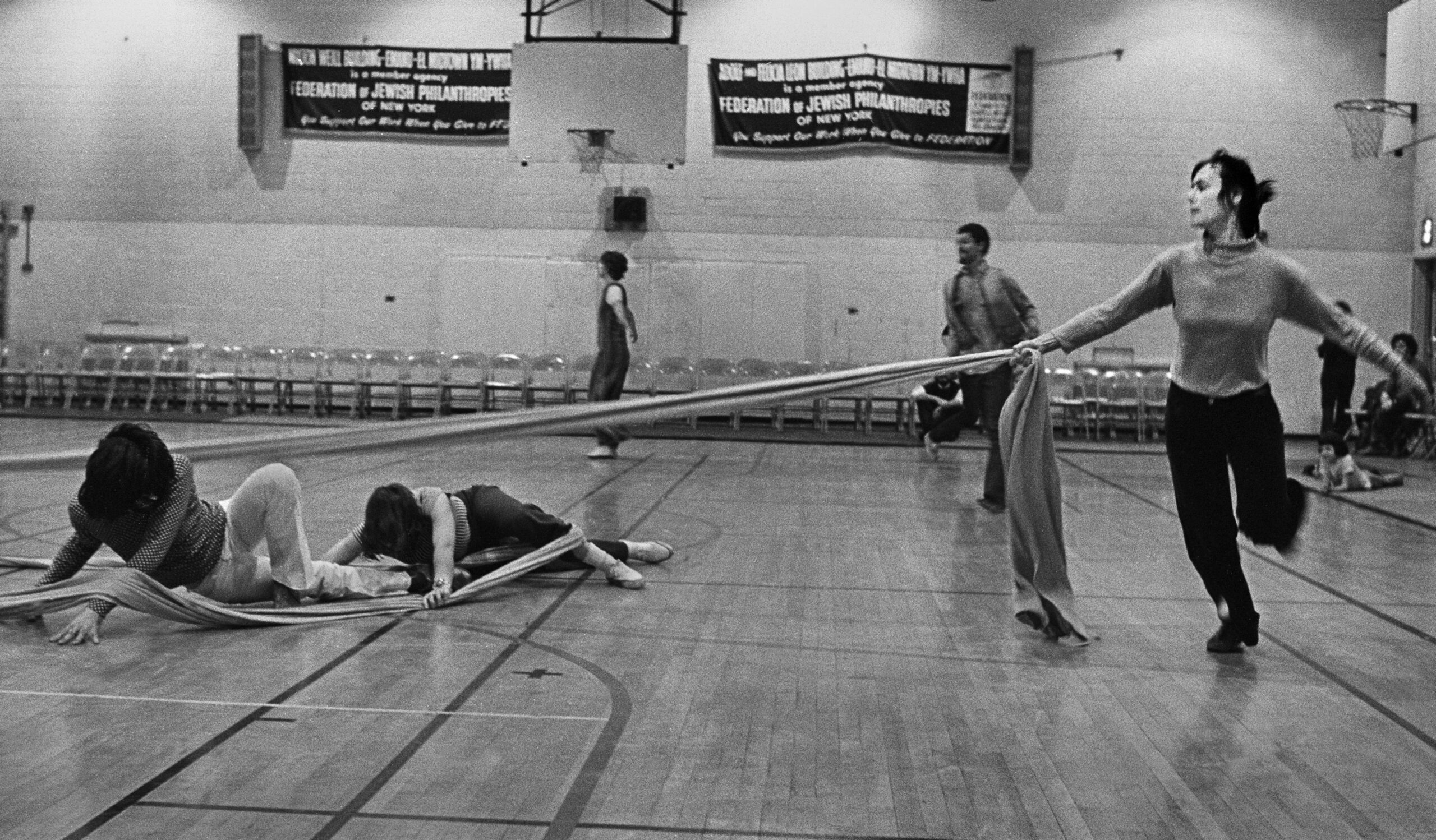

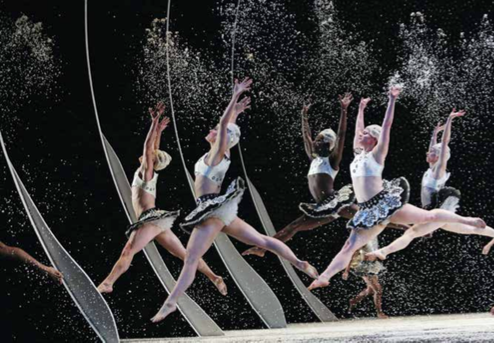

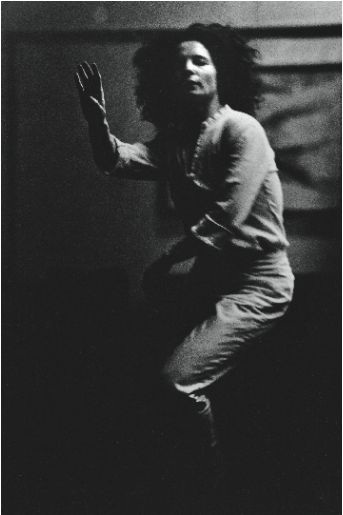

Although Deborah Hay’s solo[29] also had technical problems, it’s probably the one dance piece that created a cogent aesthetic effect. With dancers gliding by on individual remote-controlled platforms, it was otherworldly, like traveling on a moon rover. Hay was studying tai chi at the time, which gave the movement of the performers a spare steadiness. She was also influenced by the stillness she saw in traditional Japanese performing arts like bugaku (dance) and bunraku (puppet theater). At times one person would lie prone on a rolling platform, creating an almost morgue-like effect. At other times performers were walking alone or in groups of two or three. Long, translucent plastic sheets were hung in front of the audience, rendering the sixteen dancers (including herself) quite distant, as though seen through a frosty window. Hay didn’t want the audience to see the bodies clearly “but just to get almost like a mirage.”[30]

Hay’s written description focused on formal qualities: “Solo is a white, even, clear event in space. The performers are part of the space and light. . . . All movement is with the intention of maintaining a balance of order and evenness.”[31] The signaling system, however, only worked for about three platforms, so solo ended up having more walking than gliding. The dancers gradually walked in twos or threes without disturbing the calm.

Deborah Hay’s solo. Peter Moore photo showing D. Hay, at right atop platform, and Alex Hay, left, prone on platform, Getty Research Institute

Among those Hay recruited for her Armory piece were Robert Rauschenberg, the painter Marjorie Strider, and the sculptor Fujiko Nakaya.[32] They were three of the eight friends serving as remote-control operators, guiding the dancers on the rolling platforms. Hay called them “fake musicians,” because they were dressed formally in black, seated in a row, and “conducted” (or perhaps only given a starting flourish) by the composer James Tenney.[33] The real music was Funakakushi (1965) by Toshi Ichiyanagi, a protégé of Cage (and the ex-husband of Yoko Ono). David Tudor arranged for this richly textured electronic score to migrate from speaker to speaker, the effect being intermittent eruptions beneath the quietness.[34]

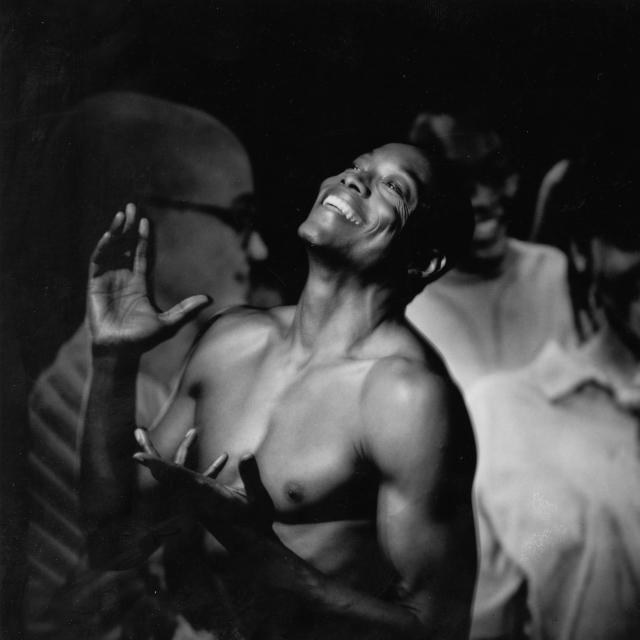

While Hay’s vision was cool and calm, her cast of characters came out of a warm, somewhat unruly environment: “What I used to do is teach free classes on Spring Street . . . several times a week and all these artists and artists’ friends and dancers would come, and I’d put on great music and half the people were stoned and we would dance for an hour.”[35]

An Unmoored Voice

There was one additional airborne element that did not come from any of the four choreographers. It came from the second performance of Rauschenberg’s Open Score. In a new concluding section, Rauschenberg picked up an unwieldy white sack and carried it from place to place. A beautiful, reverberating sound emanated from whatever he was carrying. It was the voice of Forti singing an Italian folk song from inside the bag. She was not amplified, but, with the six-second reverberation time of the Armory, her voice echoed hauntingly. As Lippard wrote, Forti sang “in a thin, clear, sweet voice that literally pierced the silence.”[36] According to Forti, “It was quite dreamlike to be in the sack singing.”[37]

Audience and Critical Reaction

The general sensibility of 9 Evenings was anti-narrative, which was part of the zeitgeist of Judson Dance Theater. That sensibility may not have translated well from a small church to a vast armory. In addition, there were long lulls due to technical problems. The performances were so low-key that the New York Times art critic Grace Glueck was able to quote a viewer saying, “Nothing’s happened yet” at the end of the first evening.[38] She also joked, with some detail, that the luminaries in the audience were more interesting than the performance. The Times dance critic, Clive Barnes, no friend of the avant-garde, called the second evening a “depressing spectacle.”[39]

Another problem was that a pro bono public relations firm had promised such a magical encounter that it backfired.[40] According to Rainer, “The whole thing was so pumped up to be a phenomenal event and the audience came with great expectations.”[41] When asked recently what they objected to, she said, “I remember they were outraged at the minimalist approach, a real letdown for them. They booed and clapped when something went on too long.”[42] Lippard confirmed that Carriage Discreteness, which she felt was one of the best works, “was greeted by the rudest audience reception.”[43]

On 13 October, Forti wrote in her report, “The audience was incensed. There was a feeling of disaster.” But, she added, “The history books are full of accounts of performances at which the audiences were incensed and that later were recognized to be important achievements.”[44] Touché!

Notes

[1]. “E.A.T.: Experiments in Art & Technology,1960–2001,” lecture by Julie Martin, Neukon Institute, Dartmouth College, 2013.

[2]. Yvonne Rainer, phone interview, 14 November 2022.

[3]. For more on Forti as a bridge between Halprin on the West Coast and Dunn in New York, see Wendy Perron, “Simone Forti: bodynatureartmovementbody,” in Radical Bodies: Anna Halprin, Simone Forti, and Yvonne Rainer in California and New York, 1955–1972, ed. Ninotchka Bennahum, Wendy Perron, and Bruce Robertson, exh cat. (Oakland: University of California Press, 2017), 88–119.

[4]. I put that word within quotation marks because, according to Julie Martin, there wasn’t enough money to pay the artists, even though Klüver and Rauschenberg, who had worked closely with Klüver to coordinate the whole series, raised a small amount of money to produce 9 Evenings.

[5]. For more on the specific ways Forti influenced Paxton and Rainer, see Perron, “Simone Forti,” 88–119.

[6]. Steve Paxton, “The Inflatables in the Age of Plastic” (transcript), ed. Tom Engels and Myriam Van Imschoot, 2019, Conversations in Vermont: Steve Paxton,

[7]. Simone Forti, phone interview with the author, 13 September 2022.

[8]. Forti, “A View of 9 Evenings,” 145.

[9]. Stephan Koplowitz, phone interview with author, 2 January 2023.

[10]. Lucy Lippard, “Total Theatre?,” in 9 Evenings Reconsidered: Art, Theater, and Engineering, 1966, ed. Catherine Morris, exh. cat. (Cambridge, MA: MIT List Visual Art Center, 2006), 71.

[11]. Paxton, “Inflatables,” 2019.

[12]. Lippard, “Total Theatre?,” 71.

[13]. 9 Evenings: Theatre & Engineering, directed by Barbro Schultz Lundestam, executive produced by Billy Klüver and Julie Martin (Lyon, France: Numeridanse, 2013), .

[14]. Colonel John Glenn was the first American to orbit Earth; he launched from Cape Canaveral on 20 February 1962. The many radio sounds for Physical Things were taped in advance.

[15]. Paxton, “Inflatables,” 2019.

[16]. See the list of objects in Yvonne Rainer, Work, 1961–1973 (Halifax: Press of the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design, 1974), 303.

[17]. Yvonne Rainer, Feelings Are Facts (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2013), 275–78.

[18]. Rainer, Feelings, 275–76.

[19]. Forti, interview 13 September 2022.

[20]. Steve Paxton, phone interview with author, 13 September 2022.

[21]. Paxton, phone interview, 13 September 2022.

[22]. Yvonne Rainer, phone interview with author, 14 November 2022.

[23]. Lucinda Childs, phone interview with author, 31 October 2022.

[24]. Billy Klüver, “9 Evenings: Theatre & Engineering; A Description of the Artists’ Use of Sound,” in Für Augen und Ohren: Von der Spieluhr zum akustischen Environment, ed. René Block (Berlin: Akademie der Künste Berlin, 1980).

[25]. Lucinda Childs, “Lucinda Childs: A Portfolio,” Artforum 11, no. 6 (1973): 56.

[26]. The sources for this description are my phone interview with Childs, e-mails with Julie Martin, and Childs, “Lucinda Childs: A Portfolio,” 50–56.

[27]. Mini-interview with Lucinda Childs, 9 Evenings, .

[28]. Childs, interview, 31 October 2022.

[29]. The title was probably based on Hay’s solo from 1965 called solo, performed at the New York Theatre Rally and at Rauschenberg’s loft. In this precursor she wore a cellophane garment and stood on a kind of skateboard.

[30]. Deborah Hay, phone interview with author, 6 September 2022.

[31]. Quoted in Klüver, “9 Evenings Theater,” 1980; and “9 Evenings: Theatre and Engineering,” Moderna Museet.

[32]. Fujiko Nakaya attended Hay’s dance sessions around the time she was painting clouds. She had met Rauschenberg when she translated for him in Japan in 1964 (during Merce Cunningham Dance Company’s world tour). In 1970, Nakaya was invited by Klüver to make a fog sculpture for the exterior of the Pepsi-Cola Pavilion at Expo ’70 in Osaka. She also became an active member of E.A.T., heading up a branch in Tokyo. Nakaya created another fog sculpture for Opal Loop, her 1980 collaboration with Trisha Brown, which is one of Brown’s most acclaimed works.

[33]. Hay, interview, 6 September 2022.

[34]. Hay, interview, 6 September 2022; and Klüver, “9 Evenings,” 1980.

[35]. Hay, interview, 6 September 2022.

[36]. Lippard, “Total Theatre?,” 66.

[37]. Forti, interview, 13 September 2022.

[38]. Grace Glueck, “Arts and Engineering Are Mixing It Up at the Armory,” New York Times, 14 October 1966.

[39]. Clive Barnes, “Dance or Something at the Armory,” New York Times, 15 October 1966.

[40]. The publicity flier, created by the PR firm Ruder Finn, claims magical acts like “You will see without light . . . You will see dancers float in the air . . . You too will float.” Flier courtesy of Julie Martin.

[41]. Rainer, Feelings.

[42]. Yvonne Rainer, interview, 14 November 2022.

[43]. Lippard, “Total Theatre?,” 72.

[44]. Simone Forti, “A View of 9 Evenings: Theatre & Engineering,”

https://monoskop.org/images/8/8b/Forti_Simone_2015_A_View_of_9_Evenings_Theatre_and_Engineering.pdf See also Clarisse Bardio, The Diagrams of 9 evenings Reconsidered: Art, Theatre, and Engineering, 1966” trans. Claire Grace (Cambridge, MA: MIT List Visual Arts Center, 2006), 45-54 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02338052/document

Historical Essays Uncategorized 2