When one downtown choreographer’s work is spread over a whole month, there is time to contemplate that artist’s work. I dropped by the Danspace Project for the first “A catalogue of steps,” part of PLATFORM 2014 on/by DD Dorvillier last Wednesday (five more to go) for half an hour of the three-hour stint, and found a quiet and concentrated space. An oasis in the middle of my week. The intensity of the dancers, especially Katerina Andreou, pulled me in immediately—and that’s hard to do without music, lights, and a crowd watching. I felt the sanctuary of St. Mark’s Church was really a sanctuary at that moment, with light streaming through the stained glass windows and the carillon chiming every half hour.

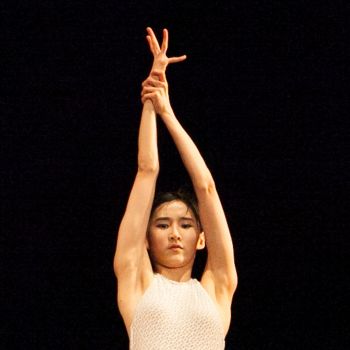

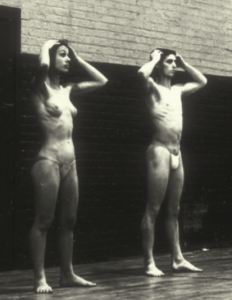

Katerina Andreou and Oren Barnoy, photo by Ian Douglas

When she dances, Dorvillier has an uncanny knack for interrupting her own flow of movement with bluntly honest radical changes. A soft caving in of the chest might make way for a carefree skip. It’s like she suddenly empties her body of all intention and quickly replaces it with a completely different intention. That kind of restlessness is hard to transfer to other dancers, but the three who are devoting themselves to these long days of “Catalogue of Steps” are doing a terrific job. They allow us to see Dorvillier’s choreographic mind at work.

When I entered the sanctuary Katerina Andreou was plowing through a physically wild solo with utmost precision while Oren Barnoy and Nibia Pastrana, sitting on the floor, were slowly leaning in toward each other in a kiss that never happened. (At a certain point the dancers changed places in this and other sequences.) The juxtaposition gave food for thought during several repetitions. Only about 15 audience members were there, free to walk around the periphery and peruse note cards used in the choreographic process.

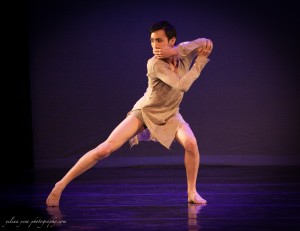

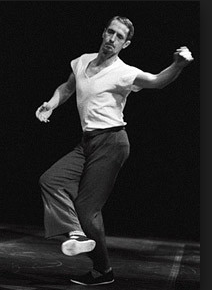

Oren Barnoy at window, photo by Ian Douglas

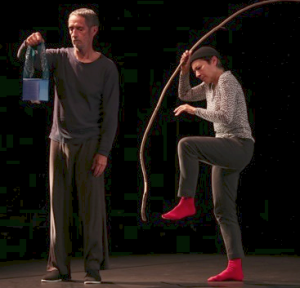

Throughout the month there will also be a series of solo performances by dance artists who have collaborated with Dorvillier like Jennifer Monson, Jennifer Lacey, and Walter Dundervill. And then, as culmination (or not) in June there will be four performances of Diary of an Image, a new work by Dorvillier with music by Zeena Parkins, lighting by the extraordinary Thomas Dunn, and Dorvillier herself dancing.

Assorted conversations in the flesh and on paper accompany this series, whose full title is PLATFORM 2014: Diary of an Image by DD Dorvillier. For full information, click here.

In NYC Uncategorized what to see Leave a comment