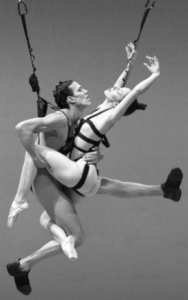

For groups that dip into the lusciously ludicrous, I vote for Ponydance. When I saw this zany quartet’s Anybody Waitin? in a tiny upstairs bar in Dublin four years ago, they crashed every idea of what good choreography is. In some ways it was more like a play, with characters who dare each other to break social barriers. But their dancing is full-throttle, top speed and, well, maybe a bit haphazard. But after a while you feel certain themes underneath. For one, the theme of waiting—although they spend no time at all standing still. This is not Waiting for Godot by that other Irish institution, Samuel Beckett.

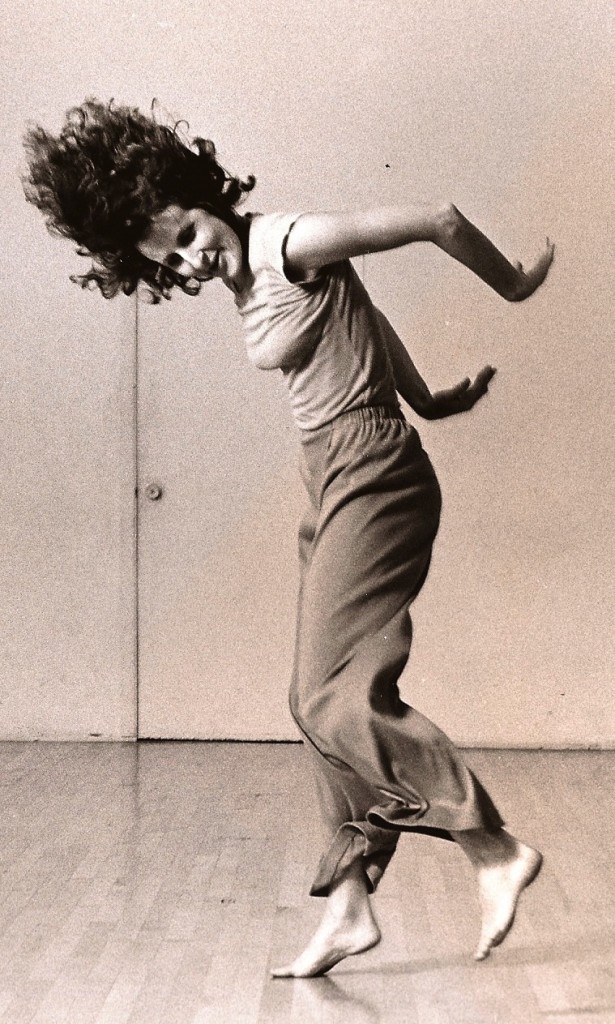

Ponydance’s Anybody Waitin? Photo by Brian Farrell

Ponydance, directed by Leonie McDonagh, is two women and two men, or, to divide it another way, three thin people and one charmingly chunky person. They pair off into same-sex duets more often than hetero; they relish interrupting each other—and the audience. In their brazenness and seeming anarchy, they remind me a bit of DanceNoise of a couple decade ago.

The aggressive manner in which they coax the audience to be part of the show could be irritating but is so bold that you find yourself laughing in disbelief. They grabbed my friend and encased him in a tiny portable tent, from which he emerged wearing a scant flowery outfit.

I’m curious to see how the barroom-brawl effect in Dublin will translate to Abrons Arts Center, October 7−10. Click here for tickets.

Anybody Waitin, which is co-presented by the Irish Arts Center, is part of Abrons’ Travelogues dance series, curated by Laurie Uprichard.

In NYC Uncategorized what to see Leave a comment