A mesmerizing dancer and an intellectual force in the field, Steve Paxton asked the most basic questions—about movement, performance, and hierarchies of all kinds. His curiosity led him to become a leading figure in three historic collaborative entities: Judson Dance Theater, Grand Union, and Contact Improvisation. For almost six decades, Paxton performed and taught around the world, earning the Golden Lion for lifetime achievement at the Venice Biennial in 2014. Since his death at Mad Brook Farm in Vermont on February 20, at the age of 85, expressions of intense gratitude have appeared across social media.

Paxton grew up in Tucson, Arizona, where he excelled in gymnastics. He also took Graham-based dance classes in community centers. To hear it from his childhood friend, the critic and educator Sally Sommer, “We partied all the time because we hung out at a friend’s ranch house, played records, and danced. We also danced at night on the tarmac of empty roads—turned on the headlights and cranked up the radio.” In school his two favorite subjects were English (hence, the eloquence of his writings) and microbiology (the curiosity of body mechanics). He attended the nearby University of Arizona, where his father was a campus policeman. He didn’t like the teachers, so he withdrew from college life.

He did like dancing. He accepted a scholarship to the American Dance Festival at Connecticut College the summer of 1958. Although the José Limón Company had provided the financial aid, it was his encounter with Merce Cunningham’s work that intrigued him. He recalled how the Cunningham company, during its first residency at this stronghold of established modern dance, caused “consternation” with his chance procedures.

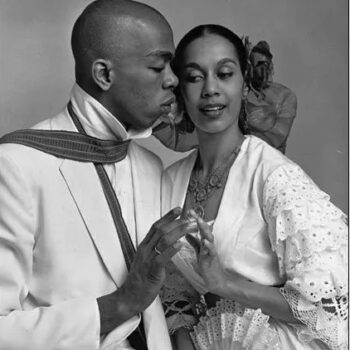

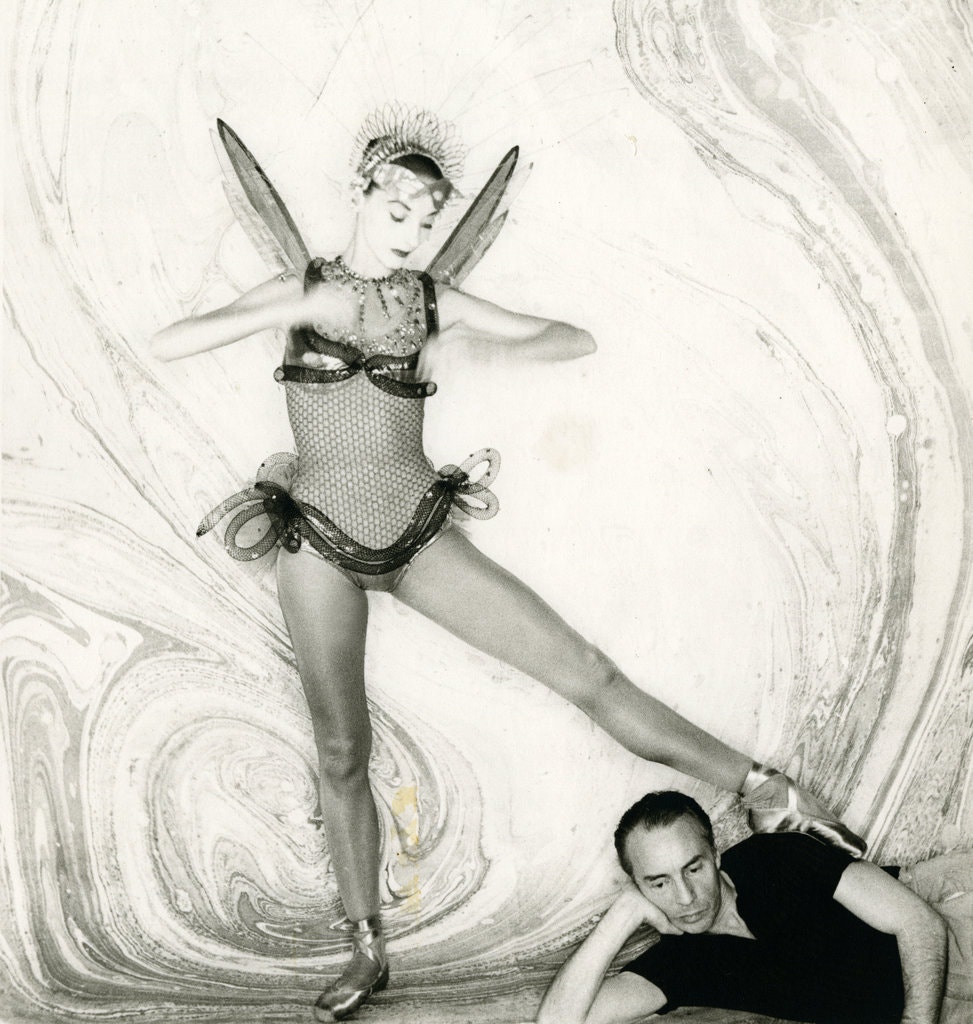

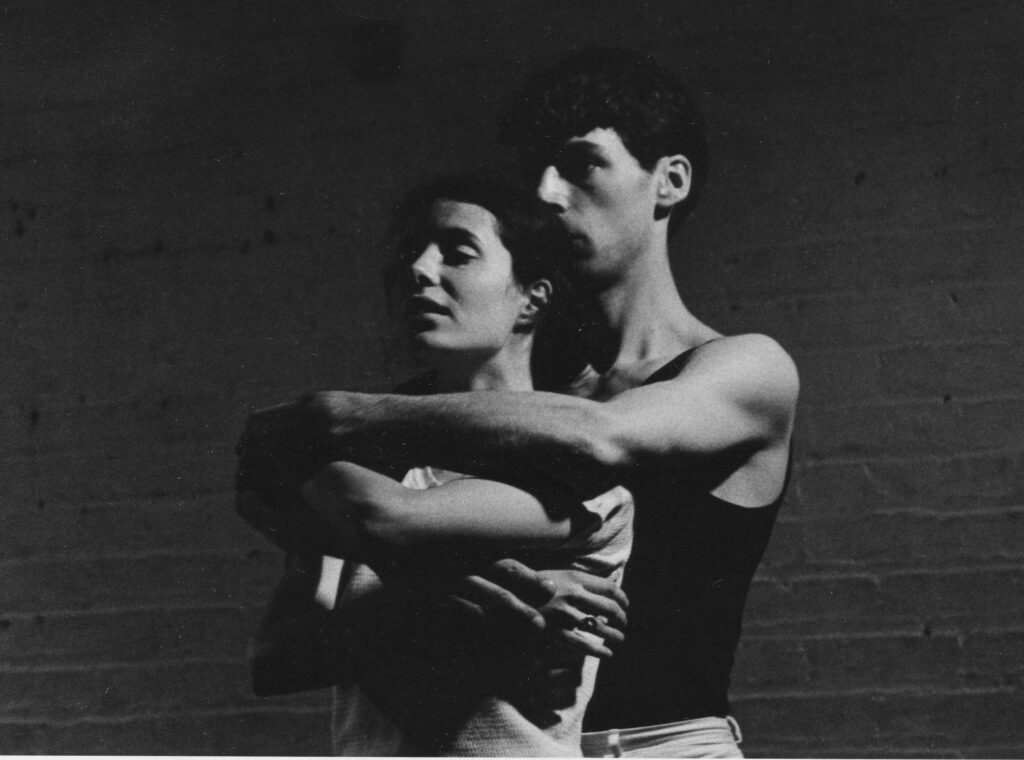

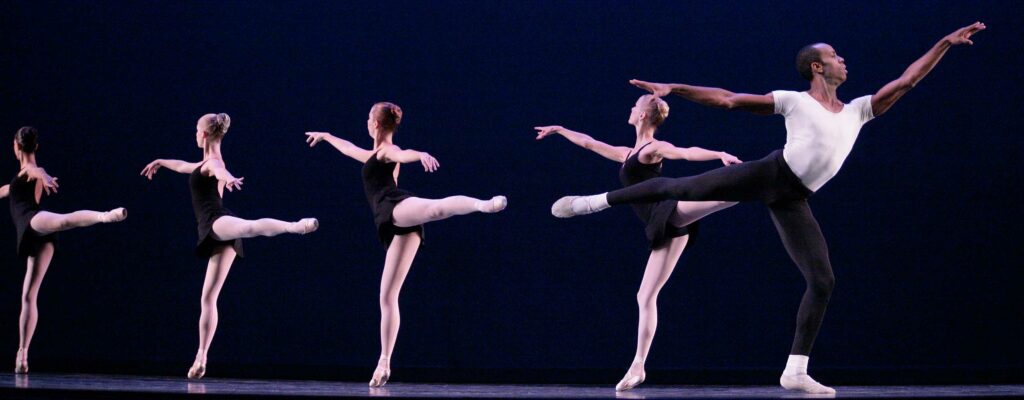

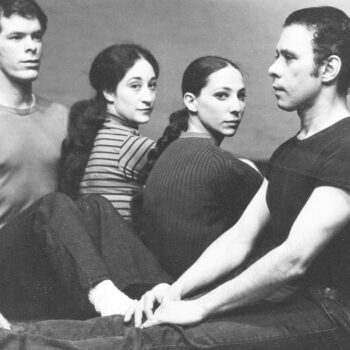

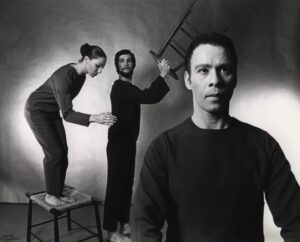

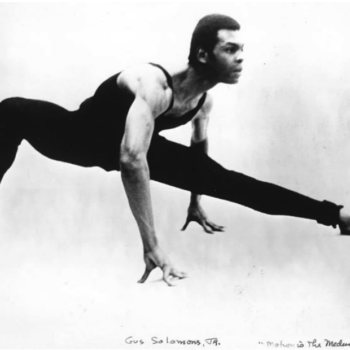

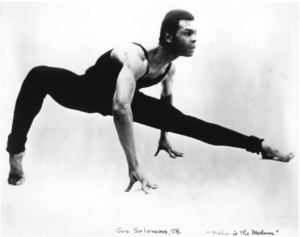

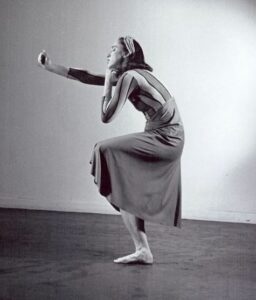

Aeon, by Merce Cunningham,1961, From left: Steve Paxton, Carolyn Brown, Judith Dunn, Marilyn Wood, Viola Farber, and Shareen Blair (on floor). Studio photo Rauschenberg.

That fall, Paxton came to New York, where he continued studying with Limón. He soon added Cunningham classes, where, as a scholarship student, he helped clean the studio. Limón’s company was in residence at Juilliard, and when the school needed more men for the restaging of Doris Humphrey’s Passacaglia, Paxton was asked to step in. (Aside: Pina Bausch, who was a student at Juilliard that year, danced the lead female role.) He later said, “I regarded myself as a barbarian entering the hallowed halls of culture when I came to New York.”

When Robert Dunn offered a workshop in dance composition at the Cunningham studio in 1960, Paxton, along with Yvonne Rainer and Simone Forti, was one of the first five to sign up. A protégé of John Cage, Dunn taught in a Zen manner, providing the space for experimentation without judgment. As Paxton has said, “The premise of the Bob Dunn class was to provoke untried forms, or forms that were new to us.”

Stylistically, Dunn stressed the value of the ordinary rather than laboring to make a dance study “interesting.” From that evolved many of Paxton’s walking dances. Why walking? Of course it fits Dunn’s request for the “ordinary.” But also, as Paxton explained in this interview, at Walker Art Center, “How we walk is one of our primary movement patterns and a lot of dance relates to this pattern.”

Fellow student Simone Forti, who had studied with Anna Halprin, produced a historic evening of “dance constructions” at Yoko Ono’s loft on Chambers Street in 1961. Paxton performed in her works Huddle, Slant Board, and Herding. Forti had no interest in technique, preferring to meld the movement function to objects. As Paxton told me in a 2015 email, he found the effort to divest from his technical training “self-shaking, paradoxical, and enlarging.”

Also in 1961, Paxton joined the Merce Cunningham Dance Company. Though bewildered at first, he loved the company and responded to the beauty and humor in the work. He felt drawn toward the Buddhist bent of John Cage and “felt at home” when listening to Cunningham, Cage, and visual collaborators Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns.

When the students in Dunn’s class wanted to show their work, they auditioned for the 92nd Street YMHA, the bastion of modern dance. Paxton, along with Rainer and Gordon, were rejected. (Aside: Lucinda Childs, however, was accepted and did perform at the Y in 1963.) So they went to Judson Memorial Church, which already housed the Judson Poets Theater and Art Gallery. Dunn’s students—who by then included Trisha Brown, Rudy Perez, Deborah Hay, Elaine Summers, and many more— collectively produced a series of sixteen numbered concerts, not all of them at the Church, from 1962 to 1964.

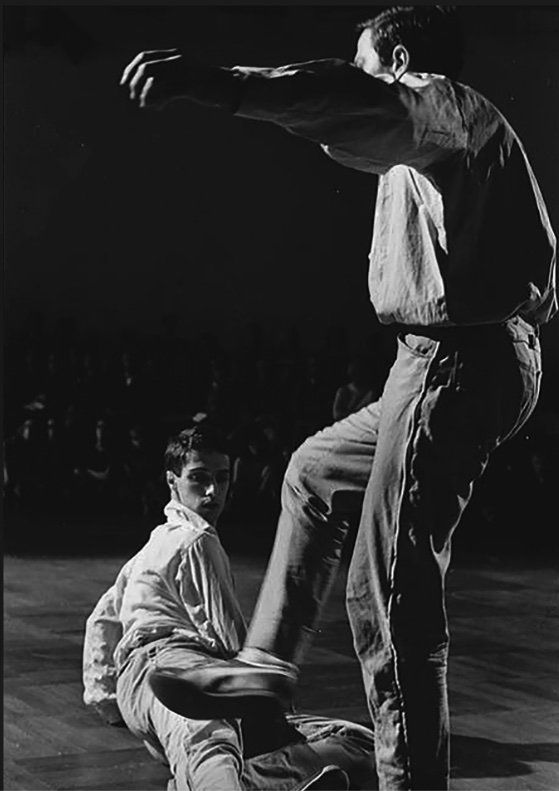

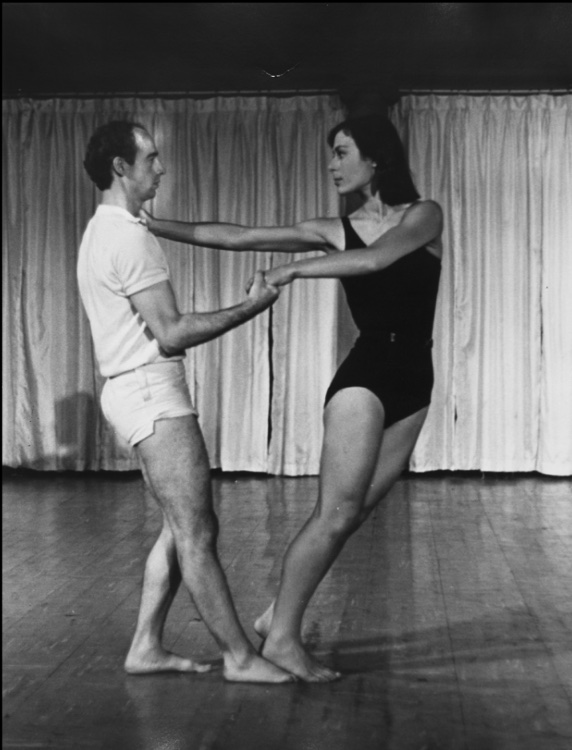

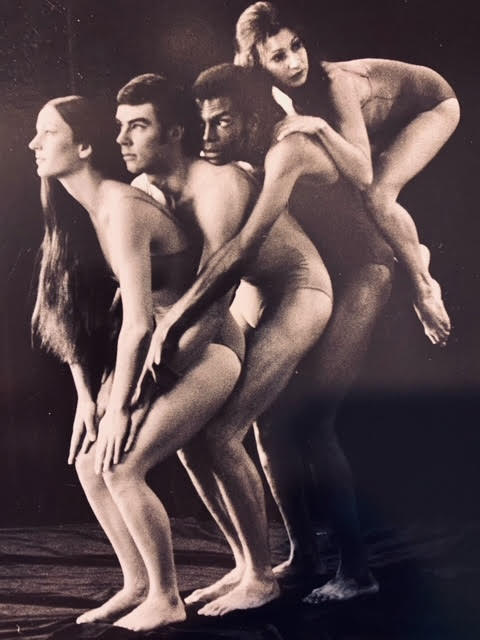

One of the early works at Judson was Trisha Brown’s Lightfall, in which Trisha and Steve perched on each others’ back until the standing person moved and the perching person slithered off. Robert Rauschenberg, who had started coming to Dunn’s classes, said, ”In Lightfall the two were just bouncing all over and under each other. The choreography seemed to be based on how much risk they could take.”

For an assignment to make a one-minute dance, Steve sat on a bench and ate a sandwich.

Paxton’s burning question at the time was Why not? About Judson Dance Theater, he said, “The work that I did there was first of all to flush out my ‘why-nots’…‘Why not?’ was a catchword at that time. It was a very permissive time.”

Yvonne Rainer wrote about his work at Judson in her memoir, Feelings Are Facts:

Steve’s was the most severe and rigorous of all the work that appeared in and around Judson during the 1960s…Eschewing music, spectacle, and his own innate kinetic gifts and acquired virtuosity, he embraced extended duration and so-called pedestrian movement while maintaining a seemingly obdurate disregard for audience expectation.”

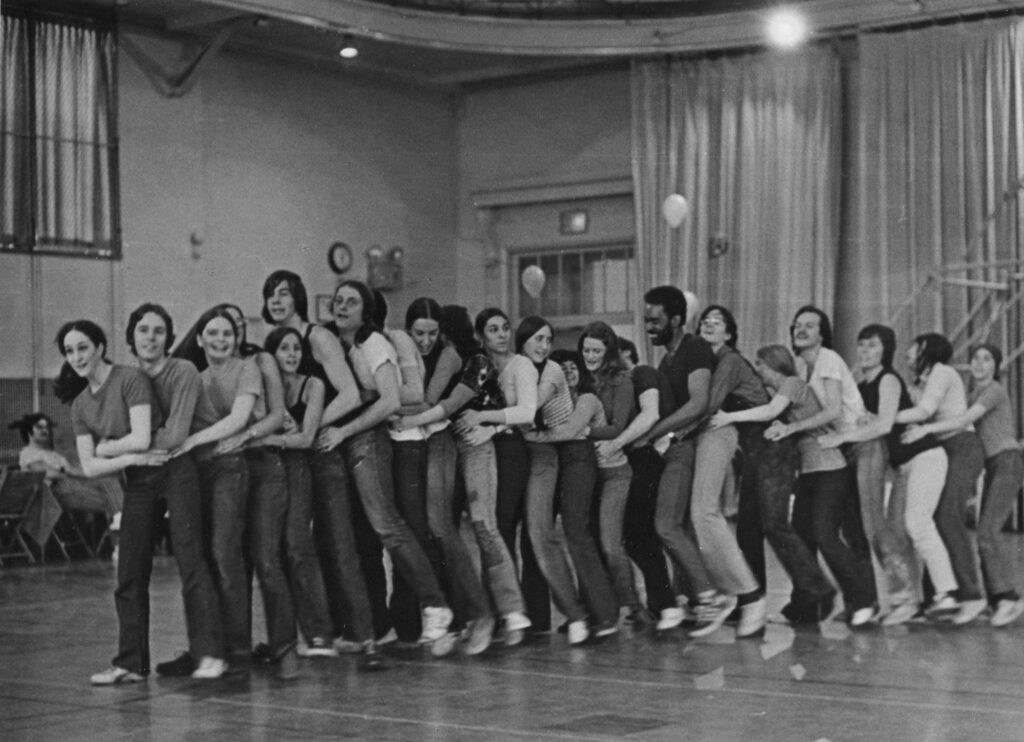

One of the landmark pieces that came out of that aesthetic, which celebrated the untrained human body, was Paxton’s Satisfyin Lover (1968). In it, a large group of dancers simply walked, stood still, or sat on a chair. Jill Johnston wrote this now famous passage in the Village Voice:

And here they all were . . . thirty-two any old wonderful people in Satisfying Lover walking one after the other across the gymnasium in their any old clothes. The fat, the skinny, the medium, the slouched and slumped, the straight and tall, the bowlegged and knock-kneed, the awkward, the elegant, the coarse, the delicate, the pregnant, the virginal, the you name it, by implication every postural possibility in the postural spectrum, that’s you and me in all our ordinary everyday who cares postural splendor. . . . Let us now praise famous ordinary people.

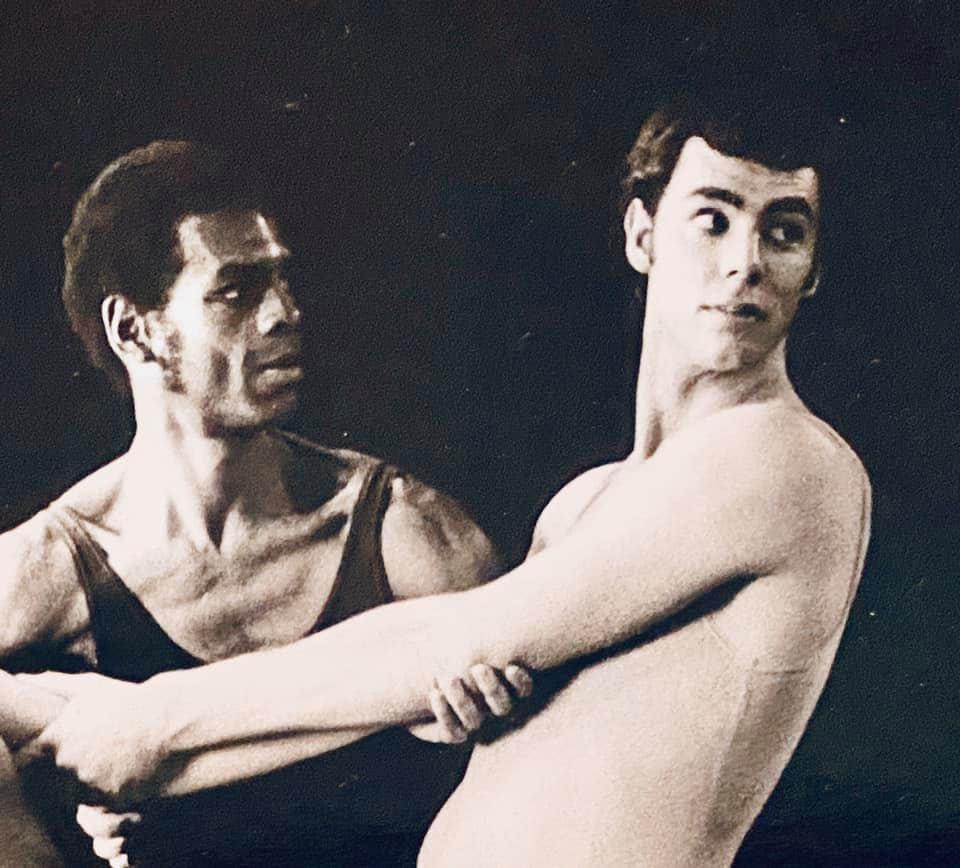

Robert Rauschenberg, Cunningham’s lighting designer and frequent visual collaborator, visited Dunn’s class and started making his own performances. Paxton was often involved in Rauschenberg’s pieces, and the two were a pair at the time. In the fall of 1964, they collaborated on one duet, Jag vill gärna telefonera (I Would Like to Make a Phone Call). This duet, based on photos of athletes, was reprised by the Bennington College Judson Project in 1982, and by the Stephen Petronio Company in 2018.

Judson Dance Theater marks a historical moment when (portions of) modern dance morphed into postmodern. At the time, Paxton thought of Judson as a place where you could just do stuff and not worry about big entertainment in big theaters. Rather than thinking they were doing something revolutionary, as Rainer felt, Paxton located himself in the lineage of modern dance tradition. In a recent Pillow Voices podcast about Grand Union, he says that modern dance—Graham, Limon, Cunningham, Humphrey, Dunham—gave permission to create new forms “from the ground up.”

For an engagement at the L. A. County Museum in 1966, Trisha Brown convinced Paxton to improvise with her. He was amazed that her loose structure elicited an immediate response from the audience; he realized the “personal element reaching through the form” was the key to the audience response—and he got hooked on improvisation.

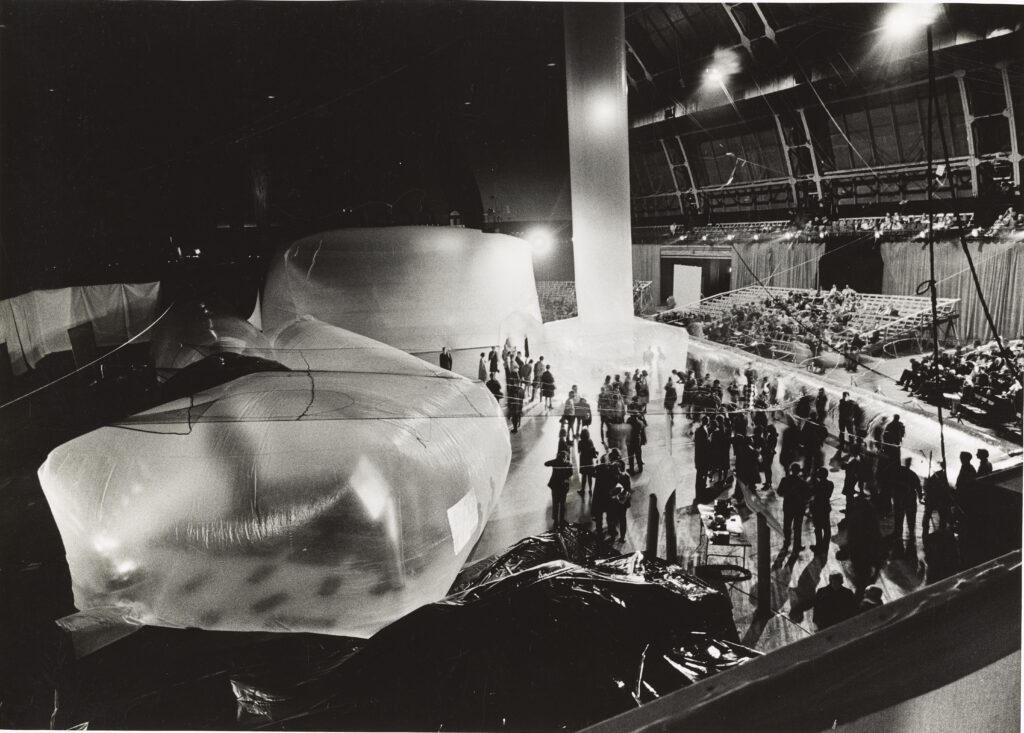

How can objects be transformative? In his surreal solo Bound (1982), Paxton wore a strange object around his neck that turned out to be a travel pillow. In some kind of endurance test, he walked slowly into a bright light, his eyes watering. For years he was fascinated by inflatable plastic sheets. In Music for Word Words (1963) at Judson Church, with the help of Rainer operating an industrial vacuum cleaner, he inflated a room-sized plastic bubble around himself, then deflated it and walked away. After several other experiments, his obsession reached its endpoint with Physical Things, the piece he made for “9 Evenings of Theatre and Engineering.” For that 1966 series in the massive 69th Regiment Armory, he created a huge inflatable tower that audience people walked through, realizing only later how toxic the plastic was.

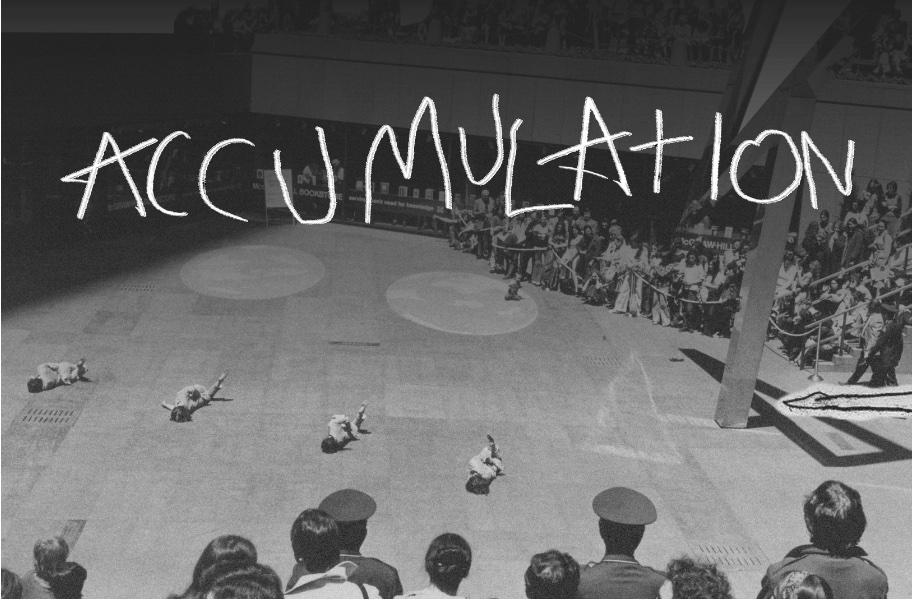

Paxton’s Physical Things, 9 Evenings of Theatre & Engineering, 69th Regiment Armory, 1966, ph Peter Moore

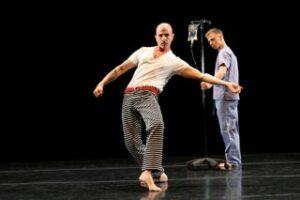

Another question was about censorship: What, really, is obscenity? For a performance at NYU in 1970, he proposed a version of Satisfyin Lover in which 42 red-headed people would be nude. The university administration nixed it on the grounds of obscenity, so he replaced it with Intravenous Lecture, in which a medical assistant injects him while he keeps talking. This piece was reprised by Stephen Petronio in 2012 with instructions from Paxton to “make it his own.”

In 1971, Paxton worked with Vietnam Veterans Against the War, who had made a documentary with testimonies of the atrocities that American soldiers committed against Vietnamese civilians. In Collaboration with Winter Soldier, he had two performers watching this anti-war documentary while hanging upside down.

In 1972, he proposed Beautiful Lecture, which juxtaposed a porn film with a film of the Bolshoi’s Swan Lake (the famous Ulanova version), to the New School for Social Research. Pressured by the authorities to omit the porn film, he replaced it with a documentary about people starving in Biafra.

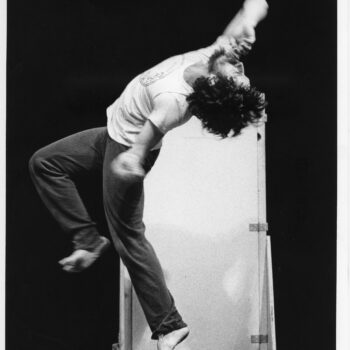

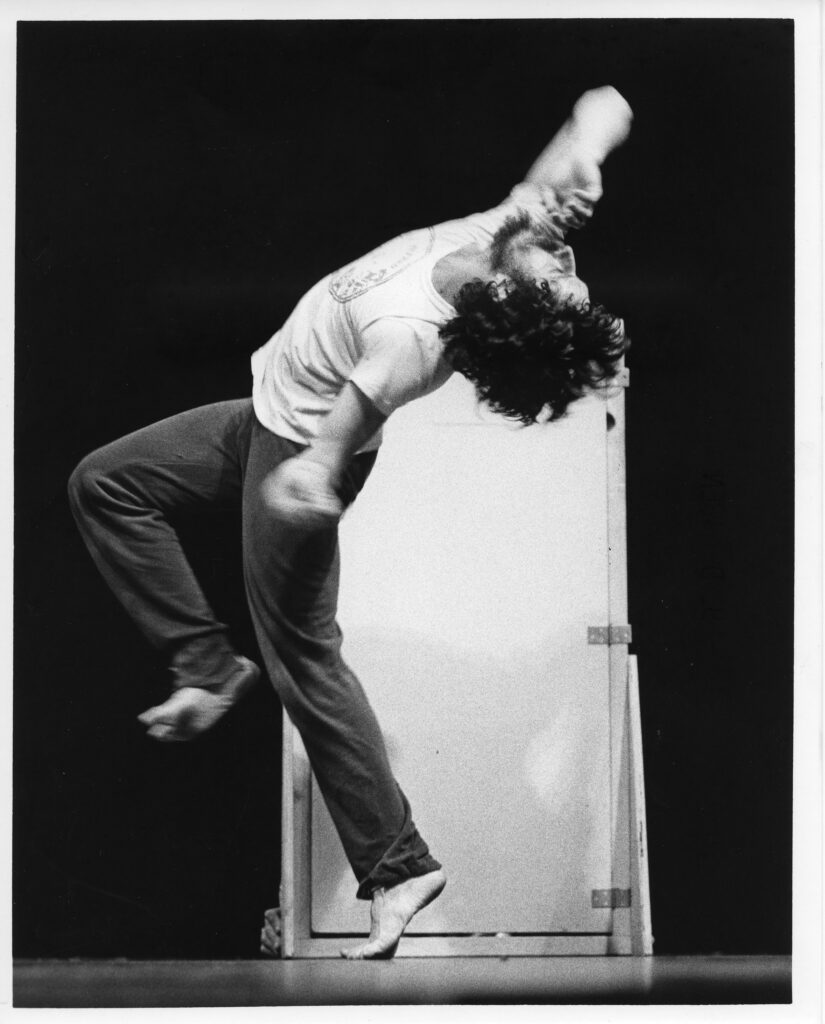

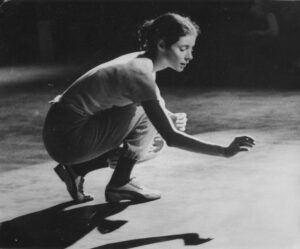

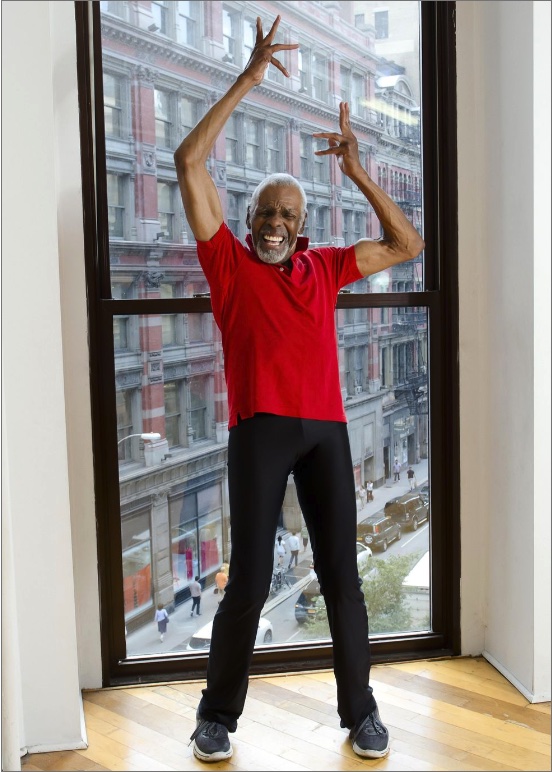

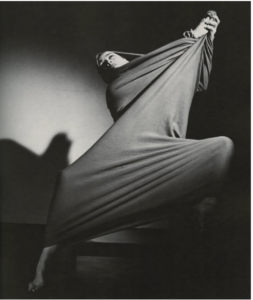

Paxton’s dancing—with his loose limbs, swerving spine, and charismatic aura—was magnificent to behold. In Terpsichore in Sneakers, Banes described him as projecting “a continuing sense of the body’s potential to invent and discover, to recover equilibrium after losing control, to regain vigor despite pain and disorder.”

At the end of the Sixties, Paxton was working with Rainer on her piece Continuous Project—Altered Daily, which changed with every performance. Rainer had given the dancers—Paxton, David Gordon, Douglas Dunn, Barbara Dilley and Becky Arnold—so much freedom that the choreography eventually blew open, obliterating previous plans. After a period of uncertainty, the group then morphed into the Grand Union, an improvisation collective with no leader. It was then augmented by Trisha Brown, Nancy Lewis and Lincoln Scott. Some of Paxton’s questions at that time were “how to make artistic decisions, how not to depend on anyone unless it is mutually agreed; what mutuality agreed means, and how to detect it.”

In the June 2004 issue of Dance Magazine, Paxton said, “Grand Union was a luxurious improvisational laboratory. All of us were very formally oriented, even though we were doing formless work.” He called the group anarchistic, which meant to him that they could do its work without a leader. He had witnessed a “dictatorial” situation and a fixed hierarchy in dance companies. For him, Grand Union “bypasses the grand game of choreography and company [where] ego-play is the issue.”

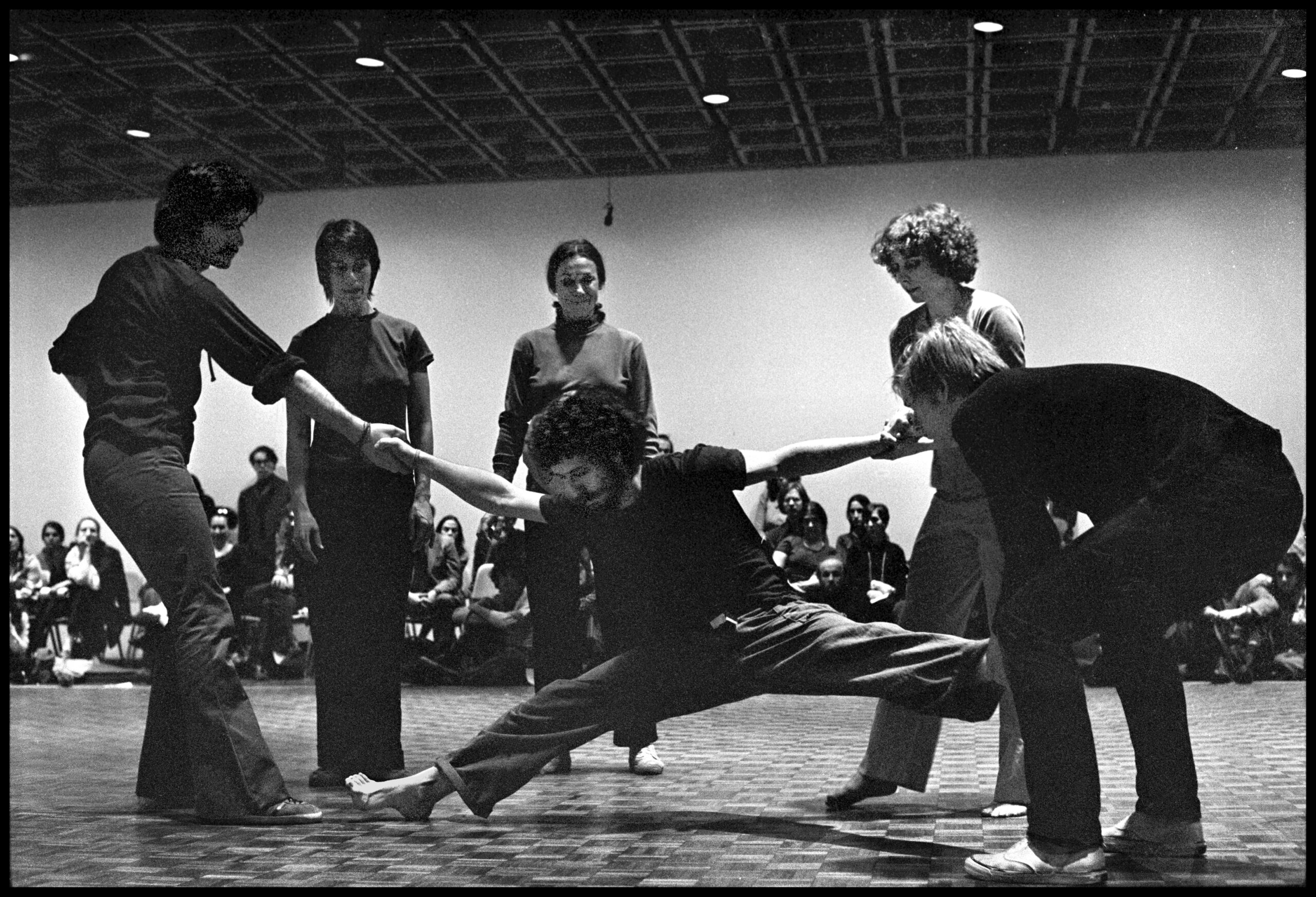

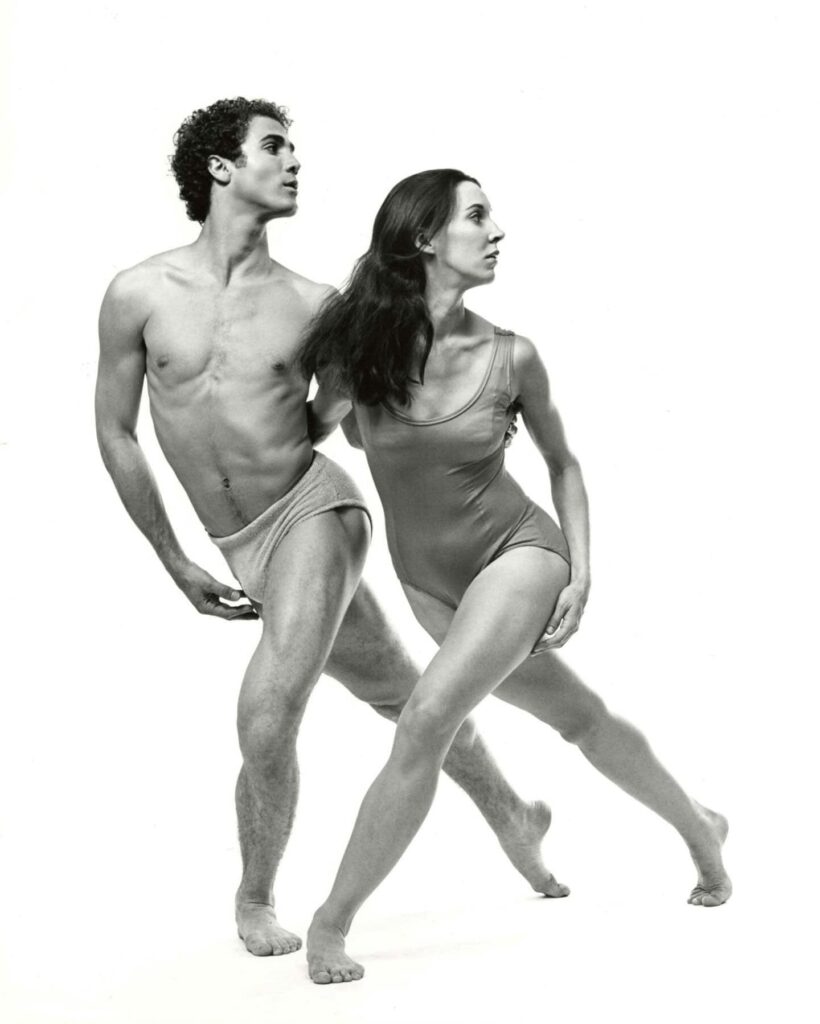

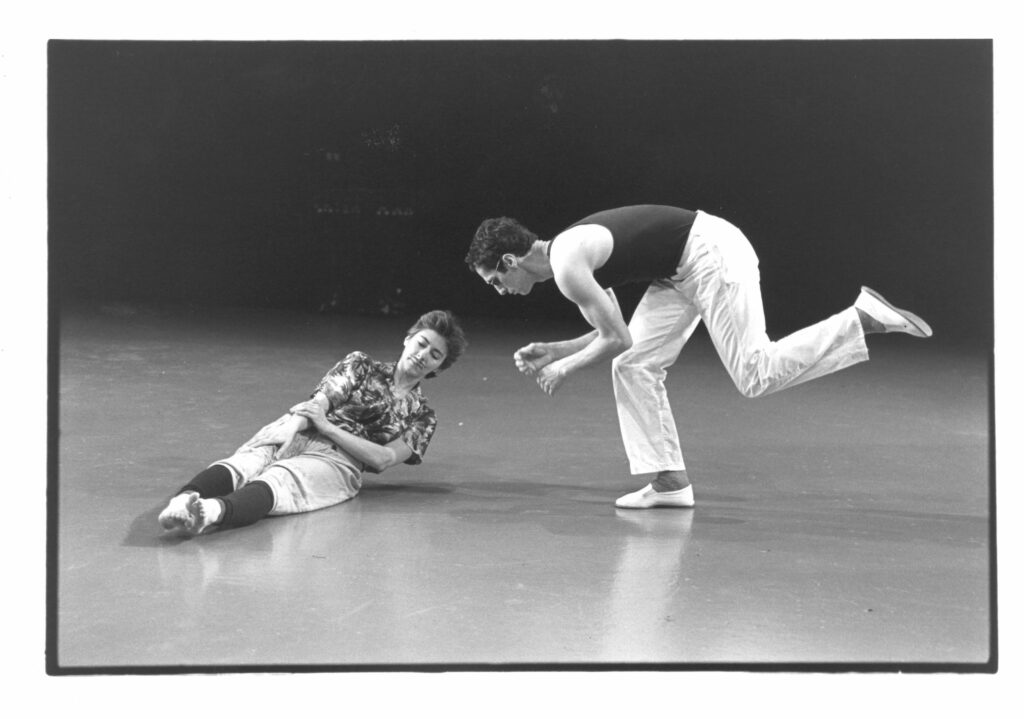

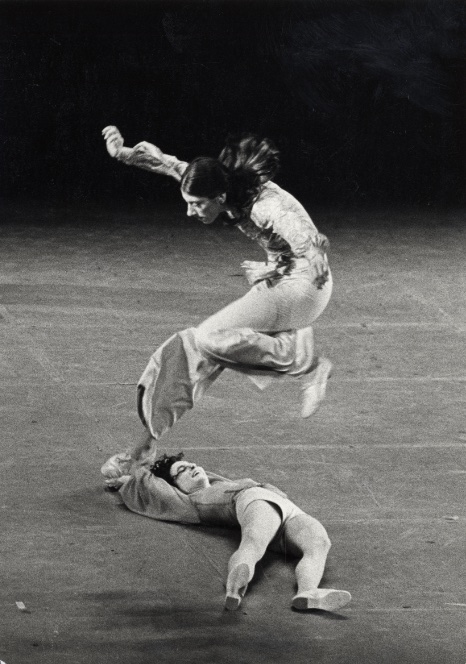

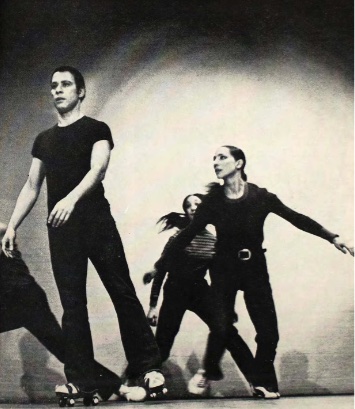

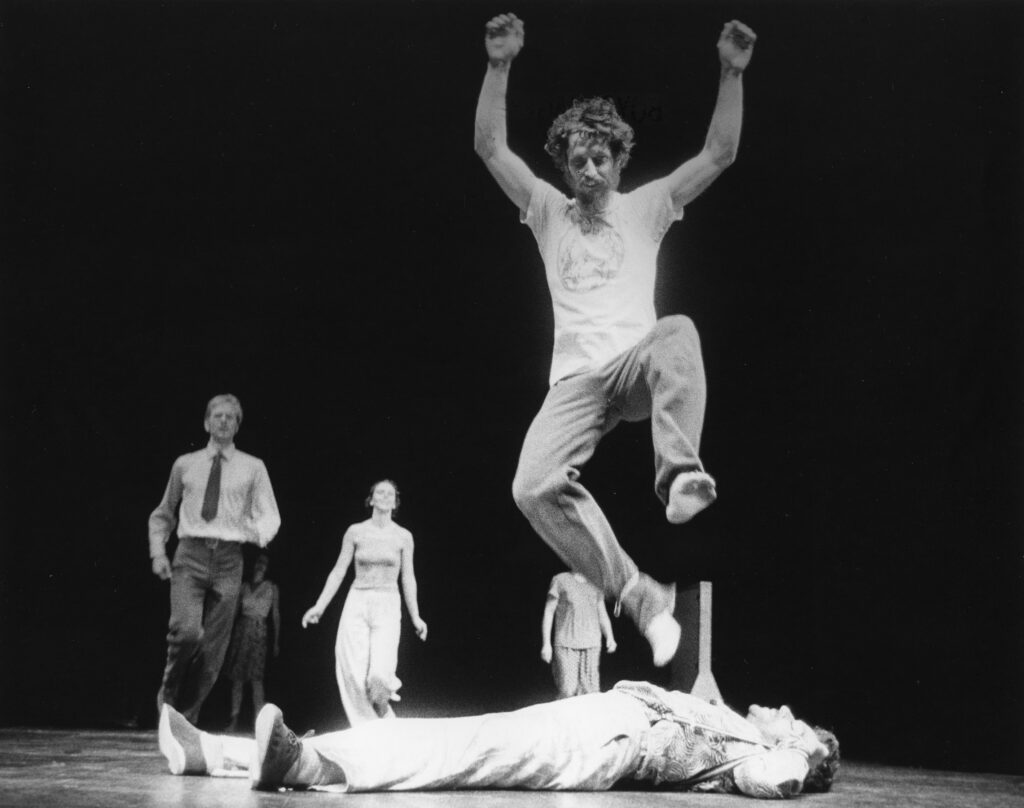

Grand Union residency at Walker Art Center, 1975. Steve jumping over David Gordon. At left: Douglas Dunn, Trisha Brown (almost hidden), Nancy Lewis and Barbara Dilley (head hidden), Tnx WAC Archives

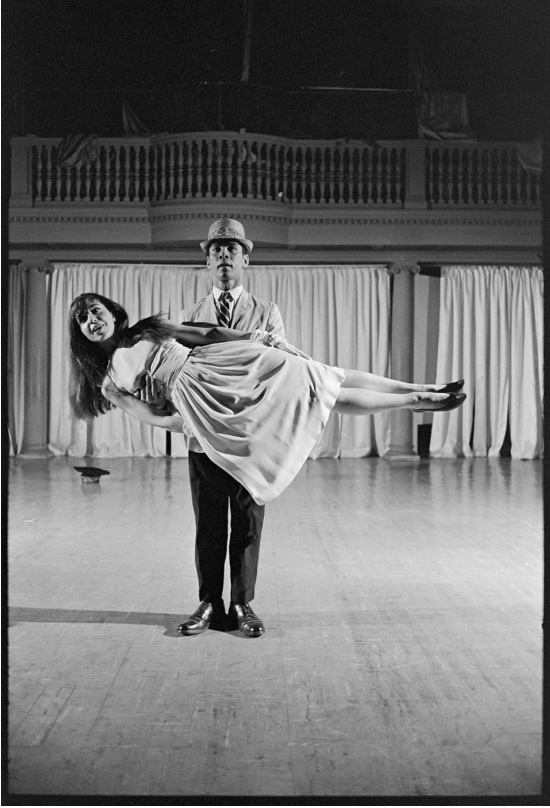

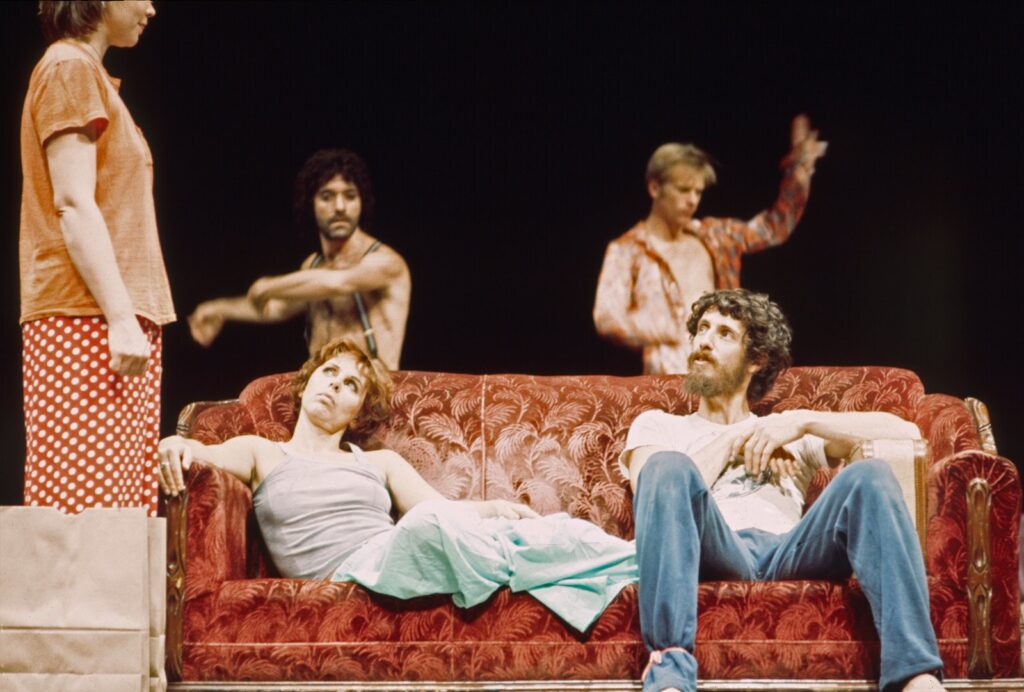

Grand Union at Walker Art Center, 1975. From left: Barbara Dilley, David Gordon, Nancy Lewis, Douglas Dunn, Steve Paxton. Tnx to WAC Archives

When Grand Union was engaged for a residency at Oberlin College in 1972, Steve taught a daily class at dawn that included “the small dance.” Nancy Stark Smith, a student, took the class and loved it: “It was basically standing still and releasing tension and turning your attention to notice the small reflexive activity that the body makes to keep itself balanced and not fall over. So you’re standing and relaxing and noticing what your body’s doing. You’re not doing it but you’re noticing what it’s doing.” This concept of noticing interior movement became foundational for Contact Improvisation.

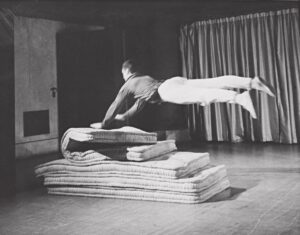

He also taught an afternoon class in tumbling just for men. The question was: How can tumbling be taught in a non-aggressive way, with soft landings? The class produced a group piece called Magnesium that was, as Paxton said, a “prototype for Contact Improvisation.” After the performance, as he recounted, “Nancy told me that if it was ever performed again, she would like to be in it. I was startled. It had not occurred to me that such a rough-and-tumble dance would be of interest to a woman.”

Although Paxton is called the “inventor” of CI, he has pointed to the mutuality of the form. It’s “governed by the participants rather than by a leader, similar to the structure of Grand Union.”

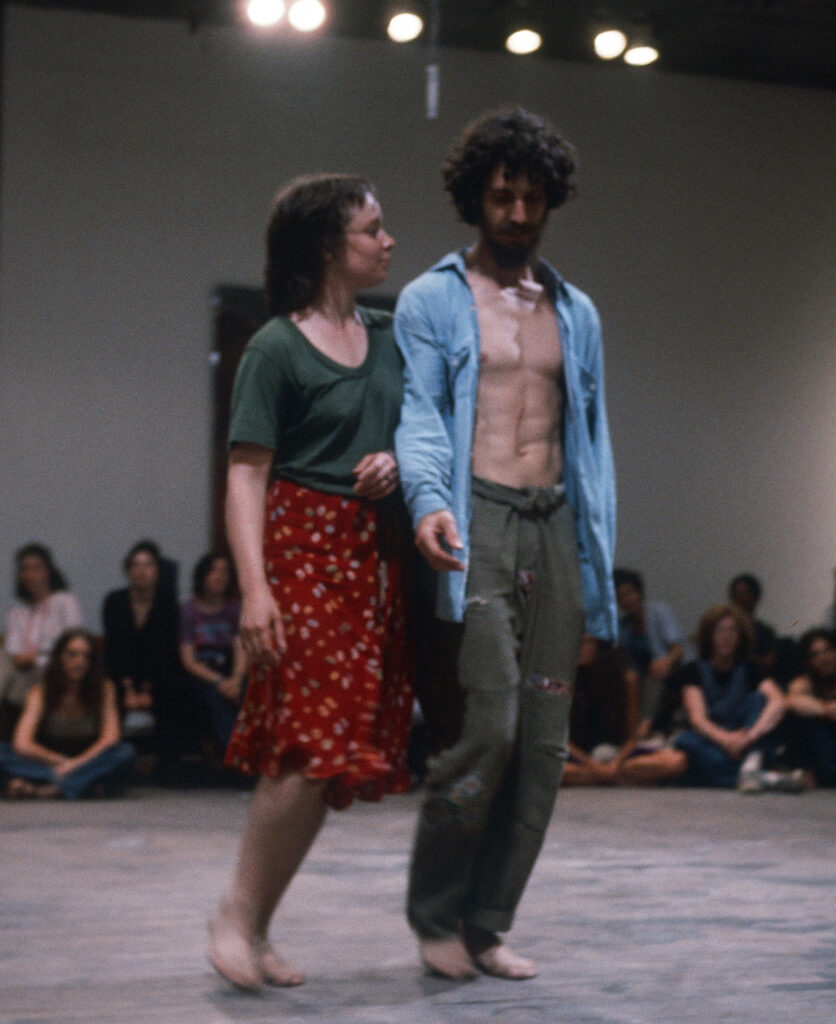

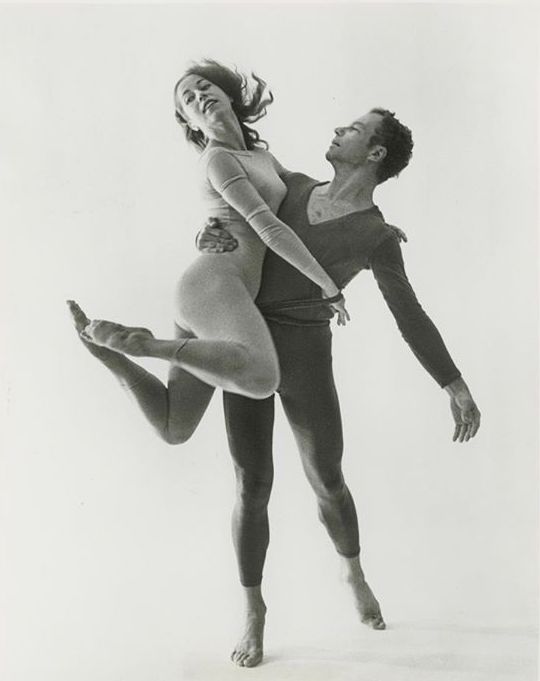

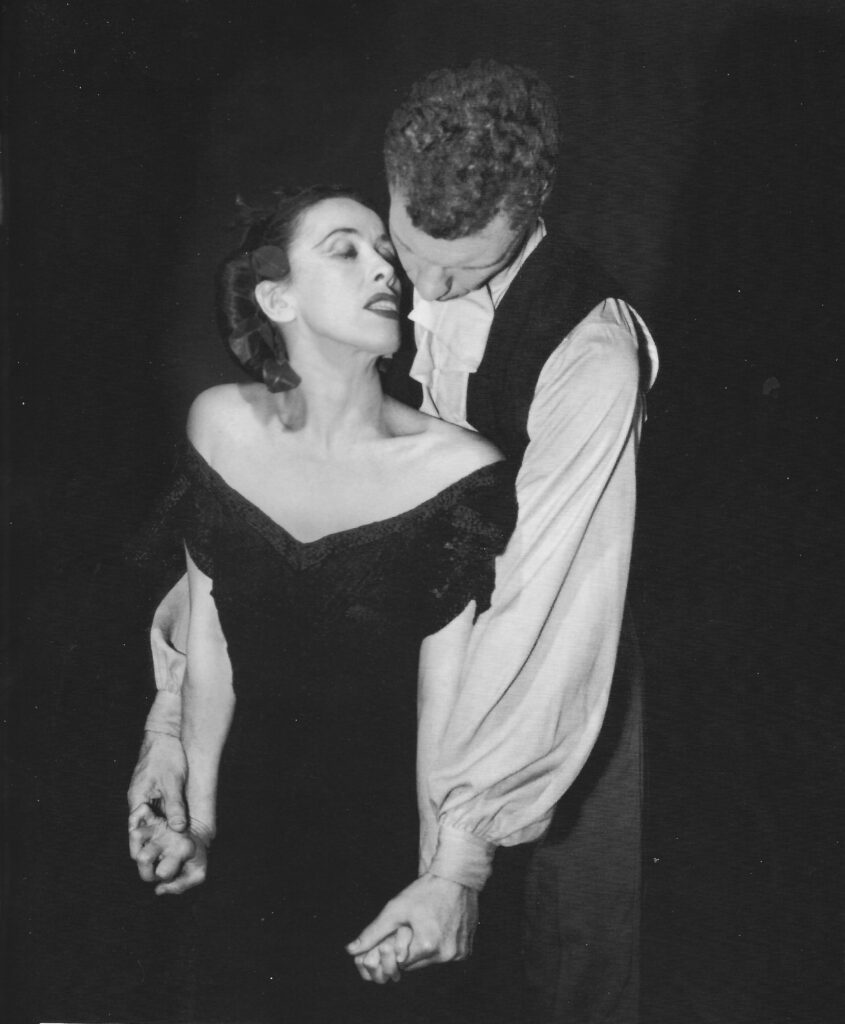

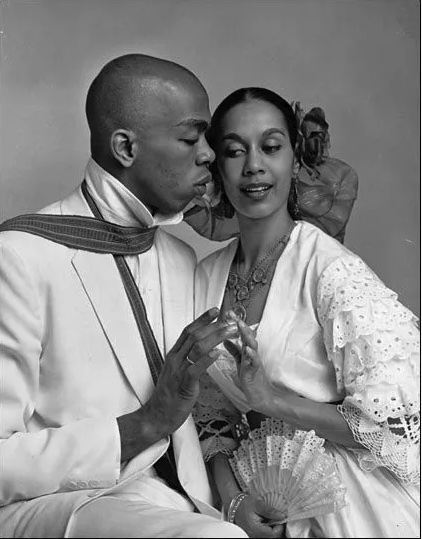

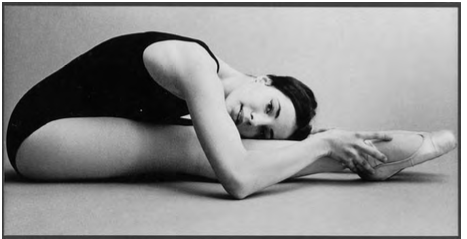

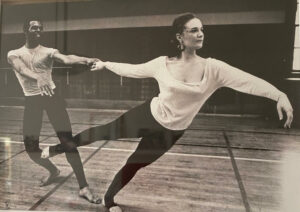

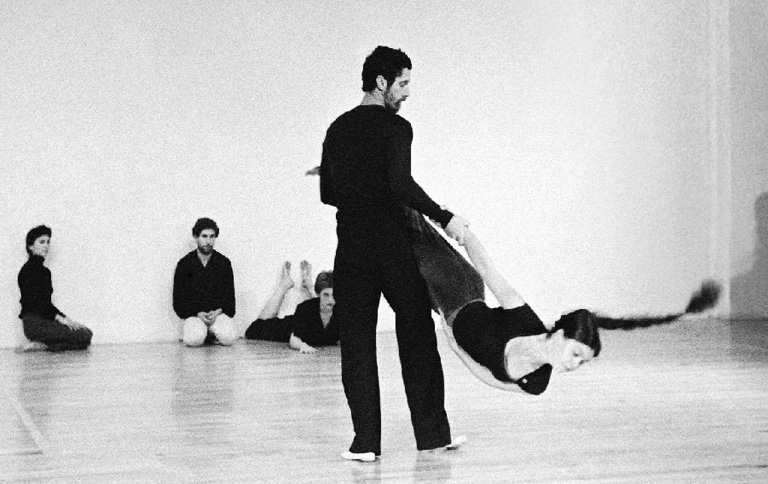

Paxton & Nancy Stark Smith in a CI performance, ph Stephen Petegorsky. Behind them are Lisa Nelson, Daniel Lepkoff, and Christie Svane. Thorne’s Market, MA, 1980.

Contact Improvisation caught on for thousands of people who wanted to move—and move with other people—but who did not want to train to be concert dancers. Paxton and Smith co-founded Contact Quarterly, which presented an alternate vision of dance with its own strong aesthetic.

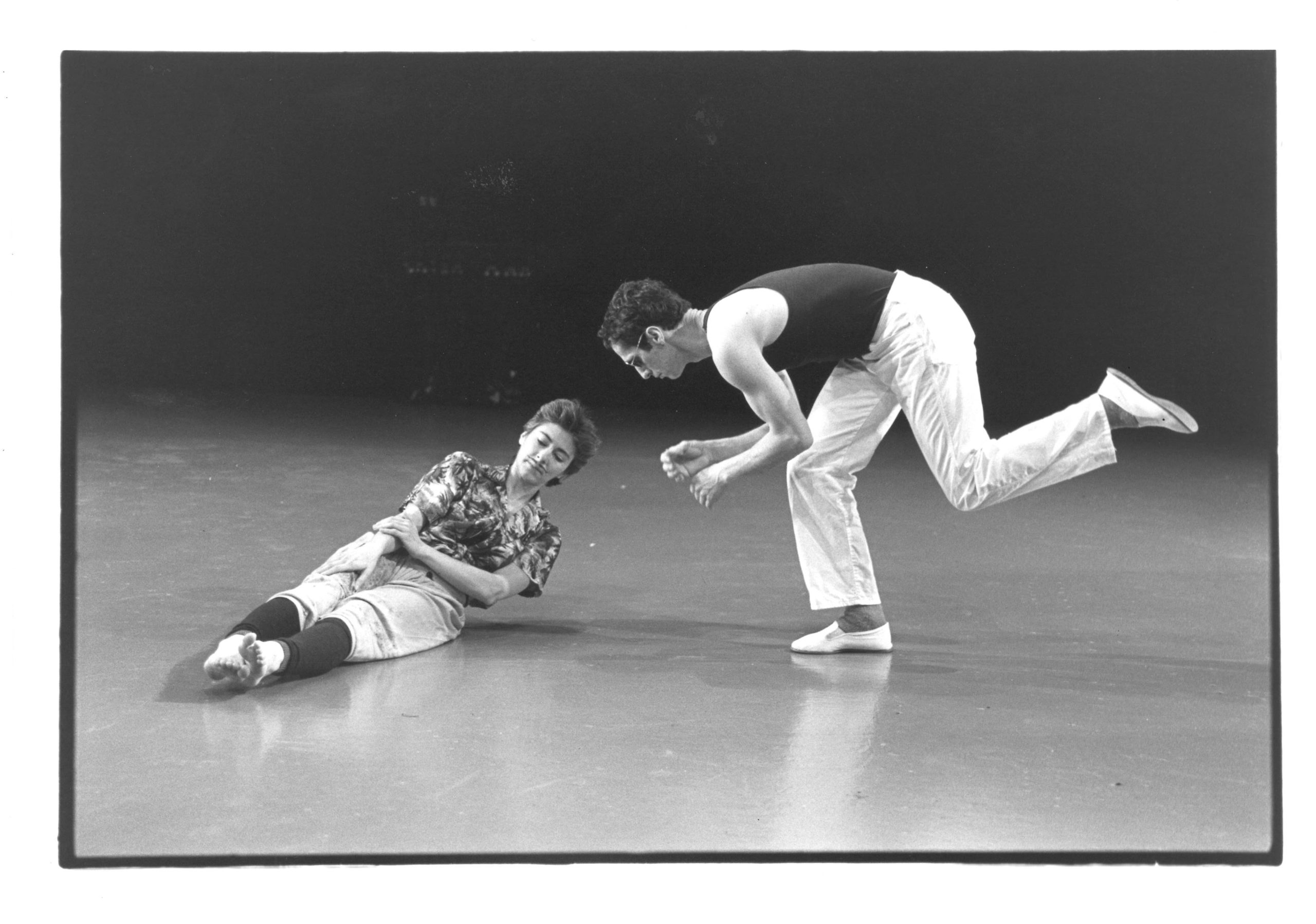

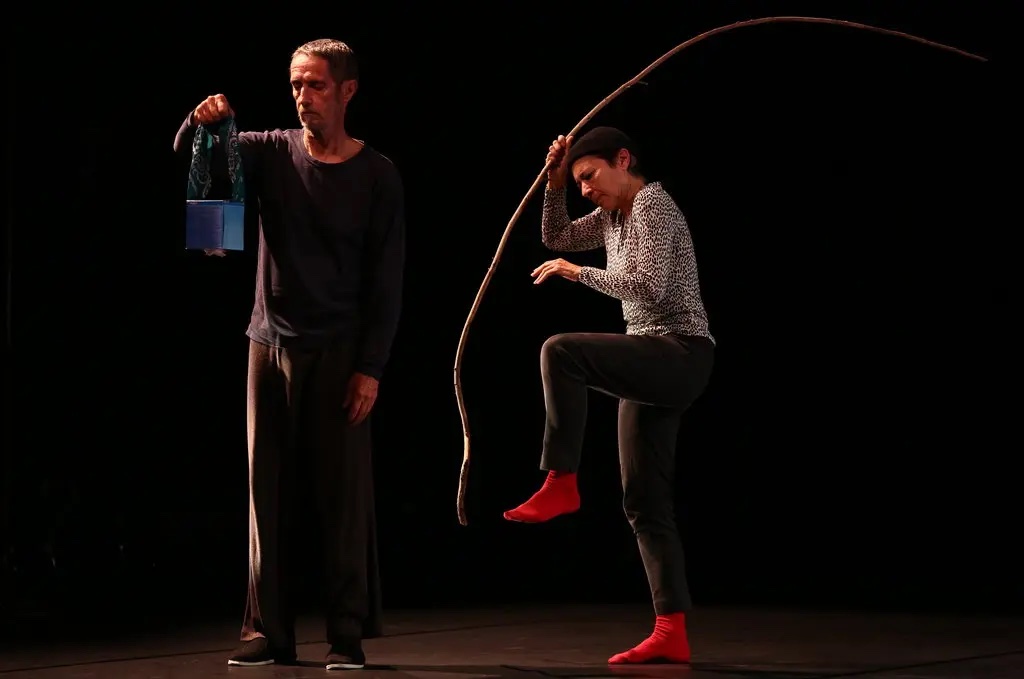

He participated in Contact Improvisation, often with Nancy Stark Smith, for ten years. Then he started developing his solo works, including his improvisations to Bach’s Goldberg Variations from 1986 to early 90s. He then developed “Material for the spine,” which he described as “what the spine is doing in that tumbling sphere with another person—a kind of yogic form, a technique that focuses on the pelvis, the spine, the shoulder blades, the rotation of the head.” He has collaborated with Lisa Nelson, fellow improviser extraordinaire and his life partner, on two entrancingly improvised duets: PA RT (1978), and Night Stand (2004). Paxton has given workshops all over the U.S. and Europe, returning to some venues again and again, especially England, Netherlands, Austria, Germany, Italy, Spain, and Portugal.

When Paxton was honored by the Danspace Project in 2014, his Judson co-conspirator, Yvonne Rainer, gave a tribute. Here is an excerpt:

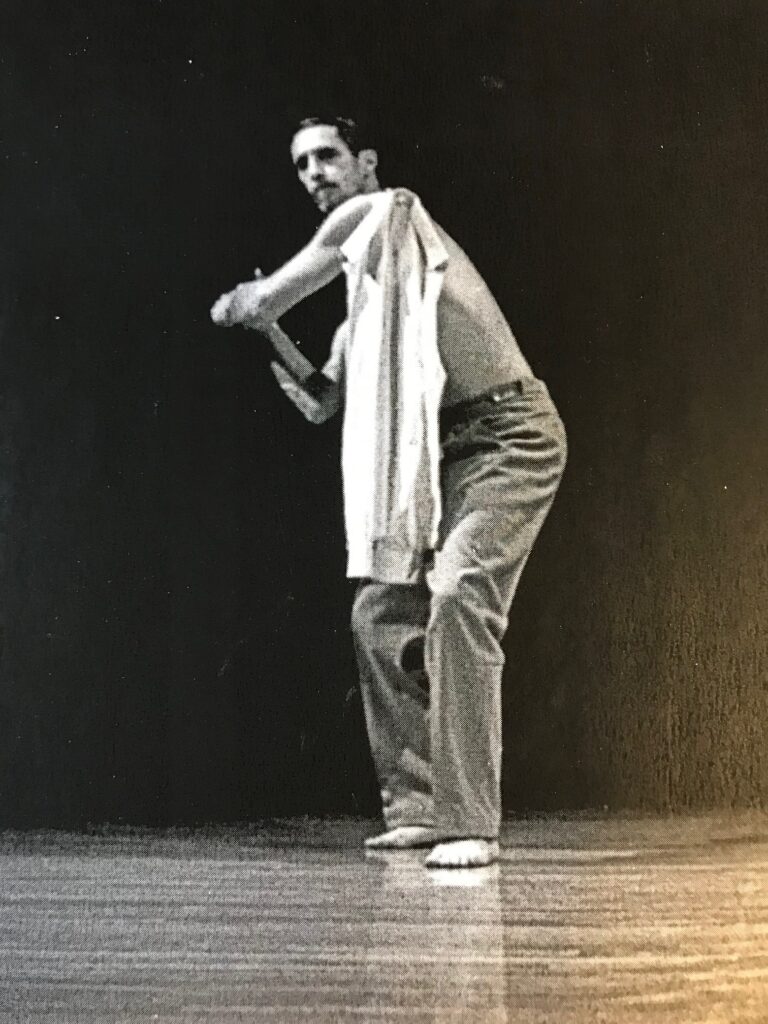

I won’t go into all the beautifully perverse and clarifying dances that Steve has created… over the years, like his performance of Flat from 1964, which I’ve heard drove members of a 2002 Parisian audience out of the theater as Steve took his own sweet time transforming himself into a clothes rack…and Proxy of 1961, which began with his promenading of Jennifer Tipton en passé on ball bearings in a washtub; and Steve’s glorious improvisations to Glenn Gould. Always we are riveted by his imposing presence and a solemnity that can morph unexpectedly into a wry comedic effect.

In 1992, his burning question was What does an idea feel like? He brought this question to a panel at Movement Research at Judson Church. His Judson-era peers —Yvonne Rainer, Trisha Brown, Simone Forti, and Carolee Schneemann— seemed stumped by this question. No one answered him straight on, so he asked again: “Does an idea have a feeling for you? If you use a stove as a score, where’s the idea?”

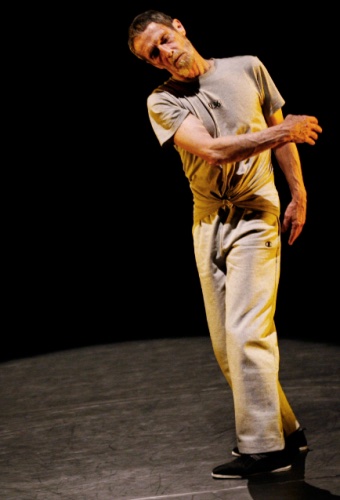

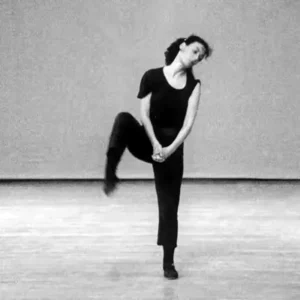

His solo The Beast (2010), in which he seemed possessed, elicited intense reactions. When he performed it at Baryshnikov Art Center, dancer/writer Lisa Kraus wrote that he “presents his own body as a locus for inquiry… His investigation has become increasingly detailed, exquisite…he is pure facet, pure torque, pure stacked bones and stretched sinew.” Amy Taubin described it in ArtForum: “If a crustacean could trace its consciousness in its carapace, it might move as Paxton did in this darkly beautiful piece, an intimate examination of the living skeleton and an evocation of what remains in the grave.” One reviewer, however, claimed that the dance was “about” old age. In this interview at Dia:Beacon, Paxton rails against the word “about,” saying “it should be stricken from the vocabulary.”

While Paxton wasn’t a warm and cuddly teacher, he was thrillingly articulate. He never faked enthusiasm. He was trusted completely by his colleagues from the Sixties—Trisha Brown, Yvonne Rainer, Simone Forti, and Cunningham dancer Carolyn Brown—in a way that I would call pure love.

Well after he had drifted away from CI, he extolled the efforts of Karen Nelson and others who brought CI to people with impairments. With democracy always in mind, he said, “that’s probably my favorite innovation in Contact Improvisation.”

Reflecting on his role in the flow of dance history, Paxton said, while interviewed by Philip Bither at Walker Art Center, that he was both a “mutant” and an “evolver” (his terms), meaning he was both a maverick for change and a stabilizing force.

Paxton always opted for the organic, close-to-nature option. Toward the end of his life, he spent much time in his garden in Vermont. In a talk at the Judson Dance Theater exhibit at the Museum of Modern Art in 2018, when asked about his life at that time, he said, “Every atom in the landscape in front of me that I look at every day is changing…I feel like it’s a living soup and I’m…kind of dissolving into its space.” He has now completed his dissolution.

Sources

Books and journals:

• Terpsichore in Sneakers: Post-Modern Dance

By Sally Banes

Wesleyan University Press, 1977, 1987

• The Grand Union: Accidental Anarchists of Downtown Dance, 1970–1976

By Wendy Perron

Wesleyan University Press, 2020

• Sharing the Dance: Contact Improvisation and American Culture

By Cynthia Novack

University of Wisconsin Press, 1990

• Taken by Surprise: A Dance Improvisation Reader

Editors: Ann Cooper Albright & David Gere

Contact Editions

• Caught Falling: The Confluence of Contact Improvisation, Nancy Stark Smith, and Other Moving Ideas

by David Koteen and Nancy Stark Smith

with a Backwords by Steve Paxton

Contact Editions, CE Books in Print

“Trance Script,” Contact Quarterly, Winter 1989 Vol. 14 No. 1, Judson Project Interview with Steve Paxton, Sept. 12, 1980.

• Avalanche, 11, 1975

• Democracy’s Body

by Sally Banes

Duke University Press, 1993

• Trisha Brown: Dance and Art in Dialogue, exh. catalog, 2002

Online resources

Contact Quarterly — for many videos and articles

Steve Paxton Talking Dance, Walker Art Center, 2014. Paxton gives a full account of his professional life with video clips spliced in, and allows questions to lead him into deep discussion.

Steve Paxton and the Walker: A 50-Year History

Steve Paxton and Simone Forti in Conversation, REDCAT, 2016, A charming performance/encounter between two old friends who are also dance icons.

Paxton Interview with Dia:Beacon, 2014

“How Grand Union Found a Home Outside SoHo at the Walker”

Featured Uncategorized 4