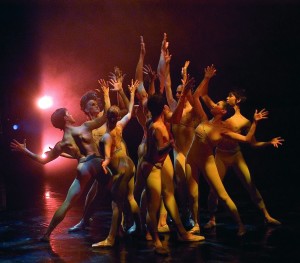

While many Americans choreographers are bee-lining it to collaborate with international composers, Donald Byrd, artistic director of Seattle’s Spectrum Dance Theater, is placing his bets on Americans. It seems preposterous, but he is choreographing seven new works for a six-day festival—exactly the number of ballets that Balanchine made for the famous Stravinsky festival in 1972. From George Gershwin to John Zorn, Byrd is determined to satisfy his American itch.

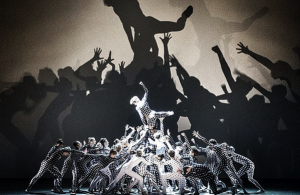

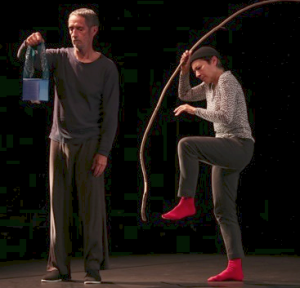

Spectrum Dance Theater in Donald Byrd’s LOVE (2012), photo by Nate Watters

The title of the festival is promising: “Rambunctious: A Festival of American Composers and Dance.” That adjective describes perfectly his premiere for Dance Theatre of Harlem last season. I was taken by—rather grabbed by—his rambunctious Contested Space, which I called “relentlessly inventive” in this posting. The first program of Rambunctious, May 15–17, includes music by Gershwin, Copland, and Persichetti, at Freemont Abbey Arts Center. For the second program, May 22–24 at Washington Hall, the composers are Wuorinen, John Zorn, and Don Krishnaswami. All the music will be played live by Seattle’s own chamber music group Simple Measures, including an overture to each performance by Charles Ives. For more info, click here. And to catch up on the voice of Donald Byrd, see his Choreography in Focus.

Around the Country Uncategorized what to see Leave a comment