I love books on dance; they are my friends. They share my sofa and my night table with me. I make new friends each year, but I do not have time to read every page of every book. However, I did read enough to absorb the scope and style of these eleven books. Loosely speaking, I would say that they all reside in the space where art meets culture. Each book deepens our understanding of what dance can be, where dance can go.

The list contains three engaging autobiographies, three gorgeous exhibition catalogs, a pair of anthologies that look at dance in an inclusive way, a quick-digest version of Jerome Robbins’ life, a re-examination of Anna Sokolow’s work, and an elegant sliver of a book of Steve Paxton’s musings. Lastly I offer a short list of other books received.

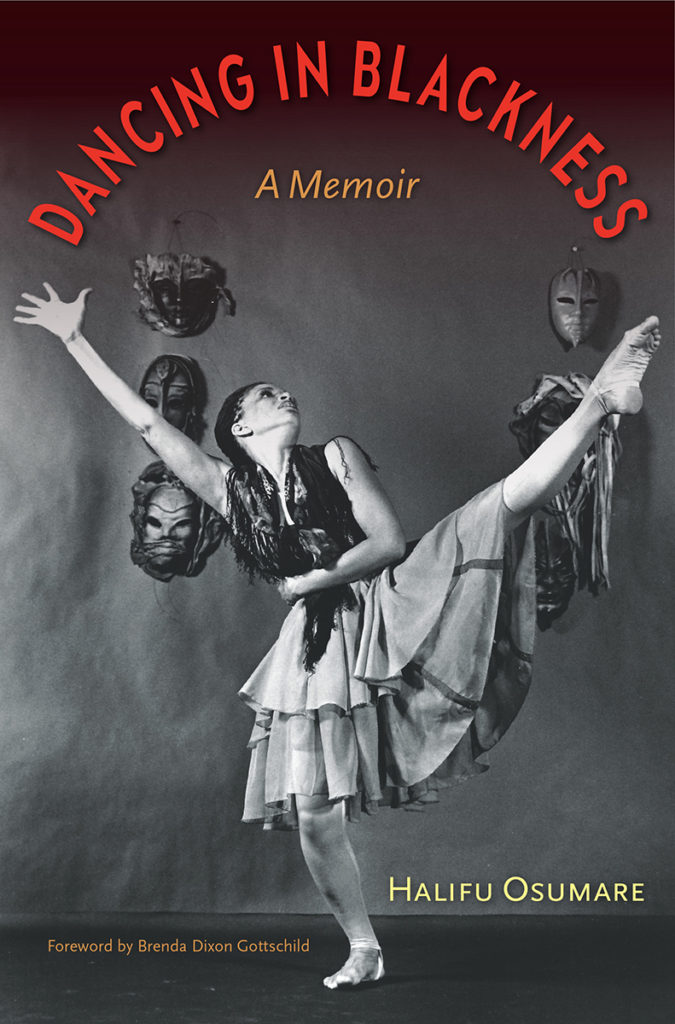

Dancing in Blackness: A Memoir

By Halifu Osumare

University Press of Florida

A lifelong dance artist, activist, and educator, Halifu Osumare takes us through her early training in the Bay Area, her teaching of “jazz ballet” in Copenhagen and Stockholm, and her growing consciousness of what it means to be a black dancer in a white world—and a dancer in a militant black world. In New York, she danced with Rod Rodgers in the early 70s, during the period when he dedicated one of his pieces to the inmates killed in the Attica prison uprising. The company performed in the ingenious DanceMobile, a kind of portable theater that brought dance to inner city neighborhoods. Back in Oakland, Osumare got involved in transcendental meditation and participated in an early version of Ntozake Shange’s celebrated play “for colored girls who have considered suicide when the rainbow is enuf.” (It was Shange who gave her her African name: Halifu is Swahili for “the shooting arrow” and Osumare is Yoruba for “the deity of the rainbow.”) She also created a lecture/performance called “The Evolution of Black Dance” that she toured to public schools.

Osumare went to Africa in search of her dance ancestry. While roughing it in a Ghanaian village, she saw, up close, how “the secular and the sacred are interwoven” in their lives. Although she was called a white woman in Ghana, when she danced with people there, she felt a sure connection.

During 12 years at Stanford (active in both the dance program and the Committee on Black Performing Arts), she was inspired to become a scholar, thinker and organizer. She earned her PhD and formed Black Choreographers Moving Toward the 21st Century, always promoting dance as a unifying force.

Evident throughout the book is Osumare’s belief in the power of dance to address social justice issues. At every juncture, Osumare asks clusters of questions—about the fluidity of tradition, about the role of dance in different cultures, about how racism affects the dance world. She gives props to the women she learned from, including Ruth Beckford (a force for dance in Oakland), Katherine Dunham, and Dianne McIntyre. Dancing in Blackness is Osumare’s third book, after The Hiplife in Ghana: West African Indigenization of Hip-Hop (Palgrave 2013) and The Africanist Aesthetic in Global Hip-Hop Power Moves (Palgrave 2008).

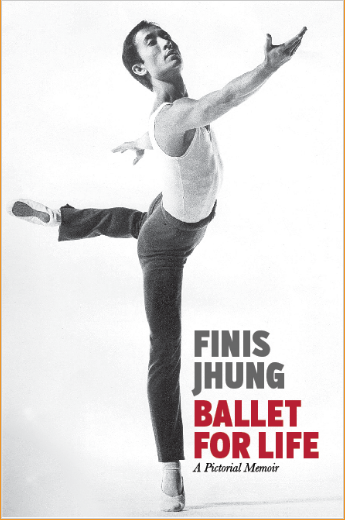

Ballet for Life: A Pictorial Memoir

Ballet for Life: A Pictorial Memoir

By Finis Jhung

New York: Ballet Dynamics, Inc

Most dance books have too few pictures, so it’s a treat to take in the bounty of photographs—more photo pages than text pages—that tell the story of master ballet teacher Finis Jhung. Ballet for Life is part autobiography, part testimonial. A small boy, growing up in Hawaii of partly Korean heritage, is so fidgety that he earns the nickname “monkey.” He becomes infatuated with ballet and performs locally. He attends the University of Utah, where he gets solid training from Willam Christensen. Although Jhung is told by classmate Michael Smuin that he will never make it as a dancer because he is Asian and has bowed legs, he rises to the top ranks in the dance department. After coming to New York to dance in the Broadway musical Flower Drum Song, he takes class at the Ballet Theatre school, where Mme. Pereyaslavec forces his turnout and destabilizes his technique. He joins San Francisco Ballet for a spell and dances in the Hollywood version of Flower Drum Song. Then he returns to New York to dance with the Joffrey Ballet.

Robert Joffrey, an excellent teacher, gets Jhung back on his center. After two years in the Joffrey Ballet (1962–64) he goes, along with many others, to the Harkness Ballet, where he stays until 1969. Along with Lawrence Rhodes, Helgi Tomasson, Brunilda Ruiz, and Lone Isakson, he dances a repertoire of works by Brian Macdonald, John Butler, Norman Walker and the company’s director, George Skibine.

After a while, his muscles get all knotted up, and he decides to listen to his massage person and become a Buddhist. He enters a less than passionate marriage, which produces his son, Jason Akira Jhung, who later helps him produce his popular dance videos. During the ’70s, while developing his craft of teaching, he founds Chamber Ballet U.S.A., a small company of excellent dancers that brings ballet to small stages and schools. It is immediately successful but lands him in debt after five years. He returns to teaching, now with a savvy business sense. One of his later projects is directing the “Billy camps” for the young boys of technical prowess who feed into the Broadway musical Billy Elliot. Ballet for Life is very readable, and the photos are a history in themselves.

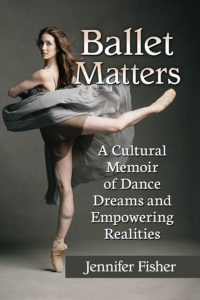

Ballet Matters: A Cultural Memoir of Ballet Dreams and Empowering Realities

Ballet Matters: A Cultural Memoir of Ballet Dreams and Empowering Realities

By Jennifer Fisher

McFarland

Let’s face it. Only a small number of ballet students ever become professional. We’ve seen lots of memoirs by famous dancers, but how does a ballet lover turn her less-than-stellar potential into an artistically fulfilling life? Jennifer Fisher, now a full professor at UC Irvine, had to re-examine her love for dance and transform it into a related career. The valuable idea here is that ballet is not always lovely and ethereal: “Ballet is not a way to escape life; it’s a way to negotiate life by learning a valuable practice, by offering complexity, depth, and beauty.” Fisher grappled with ballet as a “life force” even though it didn’t elevate her to a professional level. But even as a hobby, she says, ballet “strengthens the backbone and nourishes the soul.” The book details her encounters with ballet in Russia, her participation in Baryshikov’s PastForward project commemorating Judson Dance Theater, and her stint as a TV critic. The final chapter on “Finding My Religion” describes moments in works by Petipa, Balanchine, Ulysses Dove, and Alonzo King as windows to spirituality.

Invocation of Beauty: The Life and Photography of Soichi Sunami

By David Martin

Cascadia Art Museum

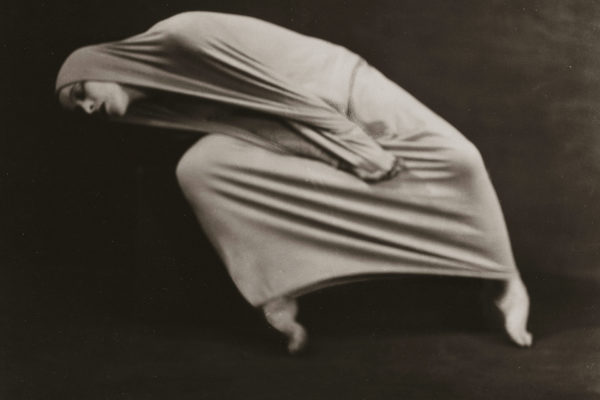

Martha Graham in Lamentation (1930)

This catalog is a visual feast for those of us who care about early modern dance. Amidst a wide range of subjects are rarely seen, luminous photographs of historic dance figures, including Martha Graham, Doris Humphrey, Charles Weidman, Ted Shawn, Agnes de Mille, Harald Kreutzerg, and Helen Tamiris. It also includes lesser known, but still intriguing, figures. One is Michio Ito, the modern dance pioneer who chose deportation to Japan rather than continue to endure an internment camp during World War II. Another is Edna Guy, the young black woman who served as Ruth St. Denis’ assistant but was not accepted into Denishawn because of her race. (She later choreographed and organized key dance concerts for black dancers.) Some of the photos, like the one of Graham in Lamentation, seem to float in space.

Soichi Sunami (1885–1971) was born in Japan and came to the U. S. in 1905. He started photographing dance concerts at the Cornish School in Seattle and then invited dancers to be his models. He moved to New York in 1922, later becoming a photographer for the Museum of Modern Art. Living on the East Coast, he evaded the mass incarceration of Japanese-Americans into internment camps during World War II. However, knowing of the government’s anti-Japanese policies, he burned his early nude studies just in case. Sunami’s photographs of landscapes are as dreamlike as impressionist paintings. His photographs of dancers make two-dimensional poetry of their dancing bodies. If you’re in Seattle, try to catch this exhibit before it closes on January 6, 2019.

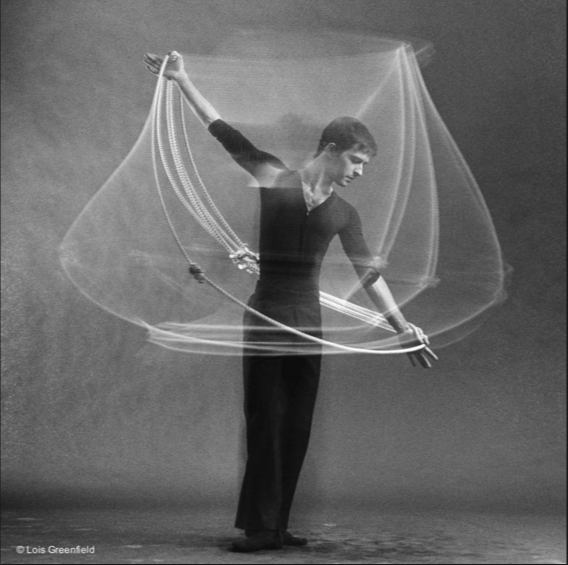

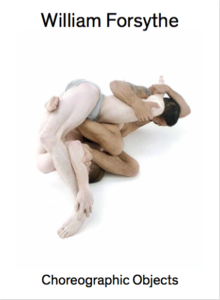

William Forsythe: Choreographic Objects

William Forsythe: Choreographic Objects

Institute of Contemporary Art / Boston

Whether William Forsythe is creating movement, sculpture, video, or interactive environments, his work retains an edge of rawness. This catalog, with images that reveal that edgy sensibility, lends insight into the mind of this brilliant choreographer. Roslyn Sulcas’ lead essay explains how Forsythe’s destabilizing techniques for improvisation carry over into his installations, creating new possibilities of dance. Browsing the book will give you a multitude of ideas for choreography. If you go to the exhibit, which is up until February 21, 2019, you are sure to get pulled into these kinetically alluring environments. This choreographic playground has traveled to many countries but has a special place in Boston, now that Forsythe has embarked on a five-year partnership with Boston Ballet.

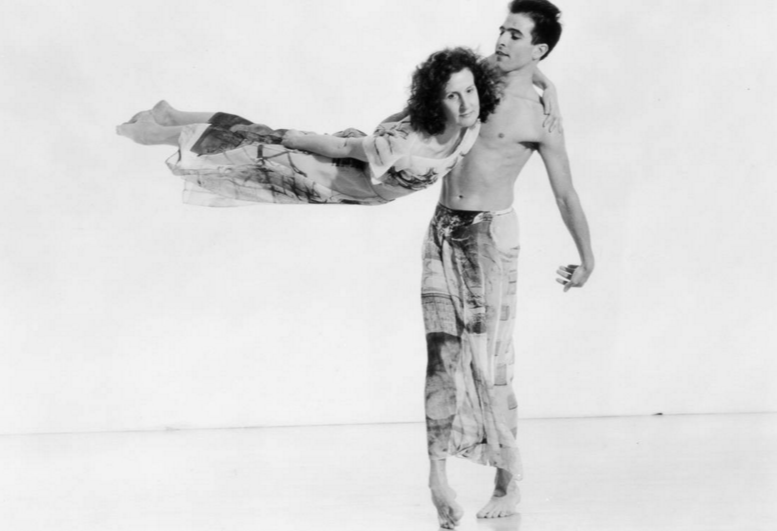

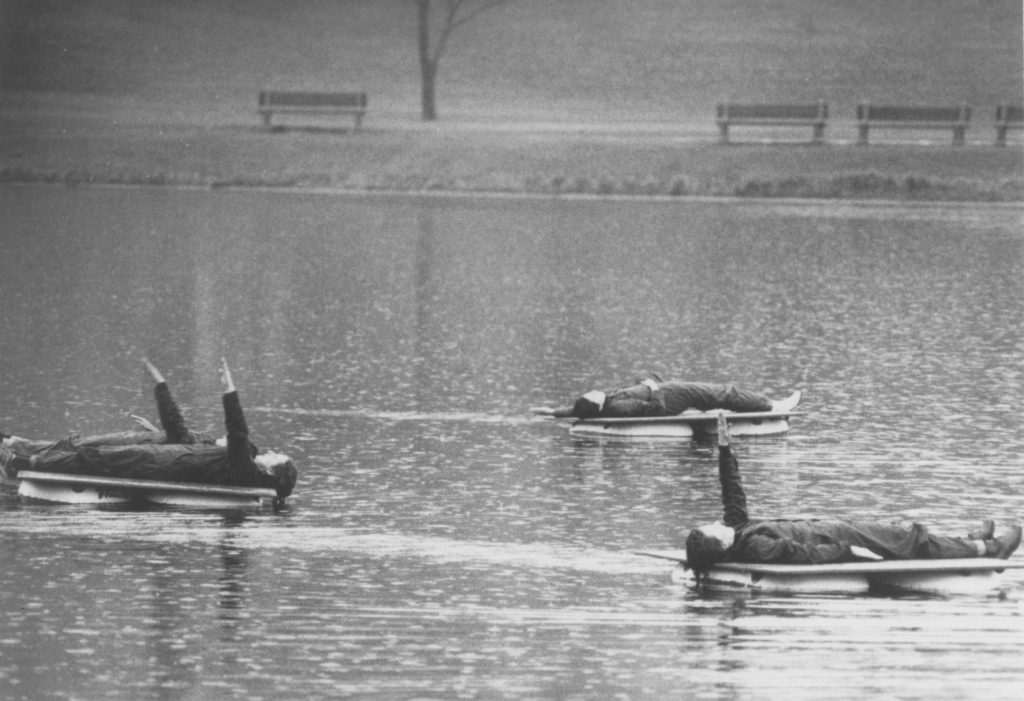

Judson Dance Theater: The Work Is Never Done

Judson Dance Theater: The Work Is Never Done

Edited by Ana Janevski and Thomas J. Lax

The Museum of Modern Art

Judson Dance Theater blasted the conventions of concert dance in the early 60s, expanding the possibilities for contemporary dance. This exhibit emphasizes the connections of Judson to the art world. It includes not only dancers like Yvonne Rainer and Steve Paxton, but also composers like Philip Corner and visual artists like Robert Rauschenberg and Carolee Schneemann. Essays by curators Thomas Lax and Ana Janevski lay out the various forms of experimentation, from outrageous to humdrum. Collaboration was in the air; so was the will to subvert authority.

The exhibit, which is up until February 3, 2018, shows the two main environments that gave rise to Judson: Anna Halprin’s workshops on her deck in California and Robert Dunn’s composition class at the Merce Cunningham studio in New York. Simone Forti’s dance constructions, bridging those two conceptual hotbeds, were a strong influence. Striking photographs from Peter Moore and Al Giese are evocative of the period, especially the sense of collectivity, the tolerance of chaos. The latter part of the catalog gives brief profiles of 34 participants and influencers, including people we don’t usually associate with Judson Dance Theater like choreographer Aileen Passloff and jazz composer Cecil Taylor. Although there are some factual errors, this catalog provides an excellent overview of a crucial period in dance history.

The following pair of books, which treats dance from different cultural points of view, is enlivening and enlarging.

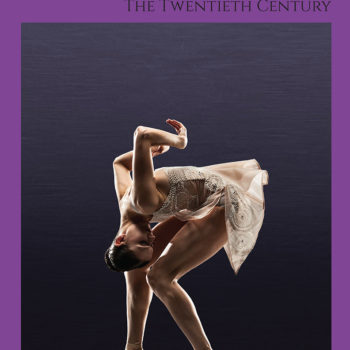

Perspectives in American Dance: The Twentieth Century

Edited by Jennifer Atkins, Sally R. Sommer, and Tricia Henry Young

University Press of Florida

This anthology of 13 essays looks at social aspects of various phenomena in dance in the United States. The entries include Julie Malnig on the racial aspects of ’50s TV shows like American Bandstand; Dara Milovanović’s connecting Fosse, fetishism and Fascism in the film Cabaret; Sara Wolf’s comparison of Isadora Duncan’s use of the flag in 1917 with Yvonne Rainer’s Trio A With Flags (1970); and Joellen A. Meglin on Ruth Page’s debt to African American jazz dance. An in-depth essay on Alonzo Kings’ LINES Ballet, by Jill Nunes Jensen, emphasizes the spiritual and global dimensions of his work. This collection reminds us that dance is everywhere—not just on a stage—and is often connected to world circumstances. Though most of the contributors are academics, they do not write in that overly pedantic way that is so annoying.

Perspectives in American Dance: The New Millennium

Edited by Jennifer Atkins, Sally R. Sommer, and Tricia Henry Young

University Press of Florida

In this second volume of the series, noted dance scholars have contributed interesting essays that are somewhat anthropological. They include Kate Mattingly on flash mobs, Hannah Schwadron on the intersection of Judaism and porn, and Patsy Gay on the Brooklyn hipster aesthetic in the club scene. The only chapter that discusses an actual choreographer is Sally Sommer’s on site-specific dancemaker extraordinaire Noémi Lafrance. Sommer analyzes two of her major works: the beautifully haunting Descent in Tribeca’s Watchtower, and Agora, which invaded the massive abandoned McCarren Park Pool in Brooklyn with a wild imagination.

Honest Bodies: Revolutionary Modernism in the Dances of Anna Sokolow

Honest Bodies: Revolutionary Modernism in the Dances of Anna Sokolow

By Hannah Kosstrin

Oxford University Press, 2017

Note: This book was published in 2017, but it slipped past me last year.

Anna Sokolow was a fierce, uncompromising dance artist. Combining Martha Graham’s modernist technique, Louis Horst’s compositional rigor, and Stanislavsky’s method of inner motivation, she created dances of haunting intensity. A Jewish dancer from an immigrant family, Sokolow naturally participated in the pro-labor, anti-fascist, socialist movement of the ’30s through the ’50s. Sokolow’s dances, says Hannah Kosstrin, were equally revolutionary and Jewish.

Sokolow’s dissent was veiled rather than blatant. Kosstrin feels that “the thematic alienation of Lyric Suite, Rooms and Opus embodied criticism of anticommunism, anti-Semitism, racism, and homophobia.” Beyond Sokolow’s own productions, she also supplied dances for communist events and pageants. “These projects evidenced her broad appeal as a communist artist who could move public masses.” She enjoyed long associations with Mexico and Israel, solidifying her alignment with the International Left.

Sokolow’s work was visceral and rebellious. As Kosstrin puts it, “Sokolow’s choreography disrupted 1950s quietism like sandpaper against a smooth surface.”

Her choreography came “from the gut.” Her endings were not final, as she wanted to allow the audience to finish the dance themselves. Says Kosstrin: “Her dances’ unresolved endings reflected Jewish modes of teaching through questioning.”

Honest Bodies is part of a recent surge of dance scholars exploring Jewishness that includes the writers Naomi Jackson, Rebecca Rossen, Judith Brin Ingber, and Hannah Schwadron. Kosstrin plunges us deep into the politics of Sokolow’s times, showing how her Jewishness is part of her idealism. I find the voices of Sokolow’s dancers are missing in this book. But Honest Bodies will acquaint you with this brilliant choreographer and the forces that shaped her.

Jerome Robbins: A Life in Dance

Jerome Robbins: A Life in Dance

By Wendy Lesser

Jewish Lives Series, Yale University Press

Writer and editor Wendy Lesser has produced a short, engrossing biography of Jerome Robbins in this year of the Robbins centennial. Relying heavily on Deborah Jowitt’s Jerome Robbins: His Life, His Theater, His Dance (2004), this slim volume is more psychologically oriented. Your heart goes out to this master choreographer who often felt terrible about himself. Lesser makes a case for him being the equal of Balanchine (which some of us had already figured out), and of his ballets being as good as his phenomenal work on musicals (that, too, is no surprise). Lesser’s descriptions of ballets like The Cage, Dances at a Gathering, and Goldberg Variations make you crave to see them again. But she comes down hard on some of his greatest ballets, like Glass Pieces and In the Night. (I’m wondering if perhaps the videos she had access to just didn’t do the choreography justice.) The quotes from Emily Coates, a dancer who worked with Robbins at New York City Ballet the last six years of his life (and who went on to dance with Twyla Tharp and Yvonne Rainer) are terrifically insightful. If you don’t have time to read Jowitt’s excellent biography, then Lesser’s book is a good short cut.

Gravity

Gravity

By Steve Paxton

Edited by Baptiste Andrien and Florence Corin

Contredanse Editions

Also available in French, tr. Denise Luccioni

This slim collection of Steve Paxton’s haiku-like writings hints at the poetic roots of Contact Improvisation. At the age of 6, he rode in a small airplane with his father, “looping and rolling in the air over Antelope Valley, Arizona.” He could see a herd of antelope below, but with the movement of the airplane, they appeared to be above or around him. Thus began the seed for the idea of spherical space that is so key to Contact Improvisation.

Paxton poses questions about the physics of the body in motion as well as the mystery of the unconscious. “I tried to catch myself behaving unconsciously, but…the perception was ruined by turning my consciousness to it…I was spying on myself. Self-hacking.” Dancers, he says, “must hack their basic movement programs in order to adapt to new movements.” One must let sensation, rather than rote memorization, be the teacher. In the Small Dance, well known to CI practitioners, he says, “Let the organs down into the bowl of the pelvis, let the spine rise to support the skull…”

Other bon mots:

On awareness: “The consciousness can roam within the body.”

The essence of CI: “Two bodies leaning and sharing mass create one center.”

Paxton’s gentle humor: After his one and only dancing/flying dream, he writes, “If such dreams were to become common, I would reduce my working schedule and nap more often.”

A reason for activism: “I diagnose the societies of the 21st century as mad. Collectively we seem to be helpless to stop the slaughter and the degradation of the very planet on which we live.”

Alighting on a definition of gravity: “Your mass and the earth’s mass calling to each other.”

Books received:

Third edition of Ballet & Modern Dance: A Concise History, by Jack Anderson. Originally printed in 1986 and re-issued in 1992, this book is valuable because Jack Anderson is a dependable source of dance history. Princeton Book Company.

Big Deal: Bob Fosse and Dance in the American Musical, by Kevin Winkler. Oxford University Press.

The Profitable Artist: A Handbook for All Artists in the Performing, Literary, and Visual Arts, edited by Peter Cobb, Felicity Hogan, and Michael Royce. New York Foundation for the Arts.

Writing and the Body in Motion: Awakening Voice Through Somatic Practice, by Cheryl Pallant. McFarland.

Lastly, this is not only a book received but a book I wrote for:

The Next Wave Festival

The Next Wave Festival

Edited by Steven Serafin and Susan Yung. Brooklyn Academy of Music. Available at Greenlight Bookstore at BAM and

Brooklyn Academy of Music in association with Print Matters Production

This book celebrates 35 years of the groundbreaking Next Wave Festival, with essays on dance, theater, music, and visual art. I had a great time digging into the rich past of Next Wave Festival. I wrote about the work of Pina Bausch, Bill T. Jones, Trisha Brown, Ralph Lemon and other dance artists who have exploded our ideas about dance in many directions.

Featured 1

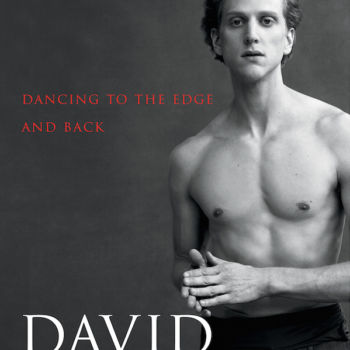

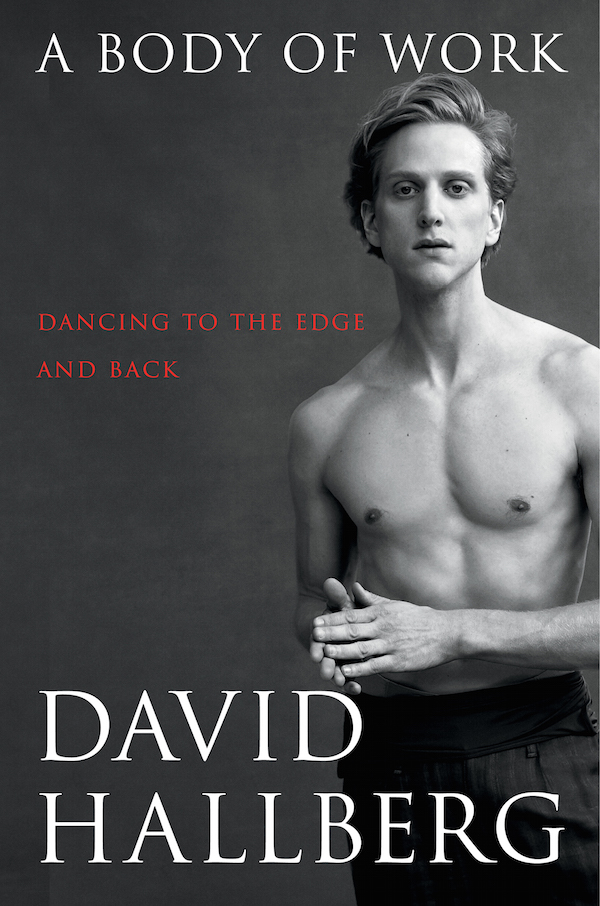

A Body of Work: Dancing to the Edge and Back

A Body of Work: Dancing to the Edge and Back Katherine Dunham: Dance and the African Diaspora

Katherine Dunham: Dance and the African Diaspora Ten Huts

Ten Huts

Mindful Movement: The Evolution of the Somatic Arts and Conscious Action

Mindful Movement: The Evolution of the Somatic Arts and Conscious Action

Prompted by something in Simone’s poignant letters to Anna, 1960-61, which are published for the first time in our

Prompted by something in Simone’s poignant letters to Anna, 1960-61, which are published for the first time in our

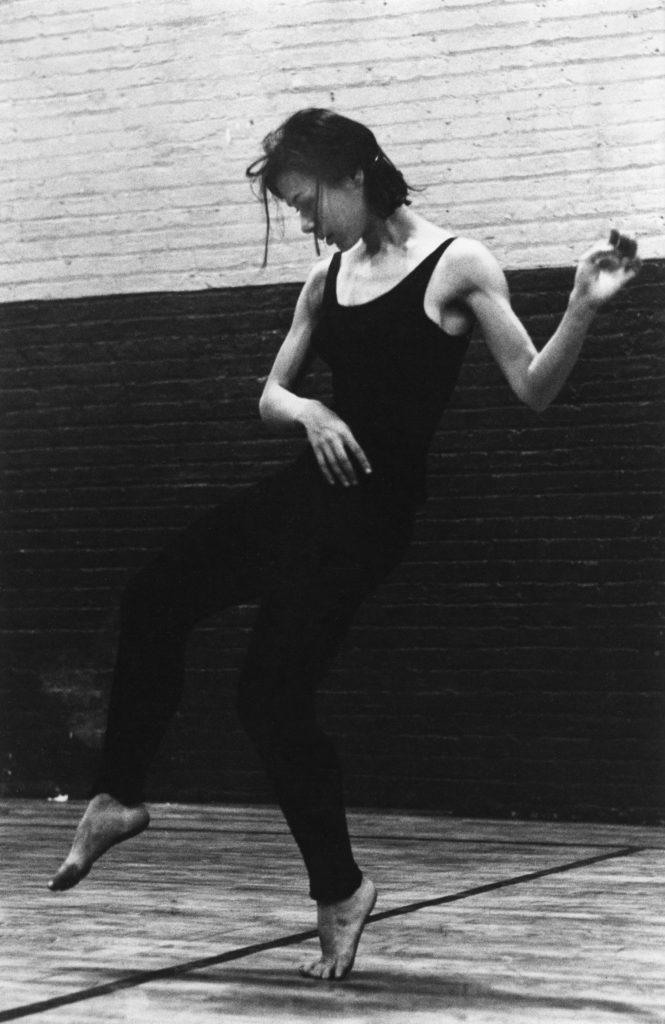

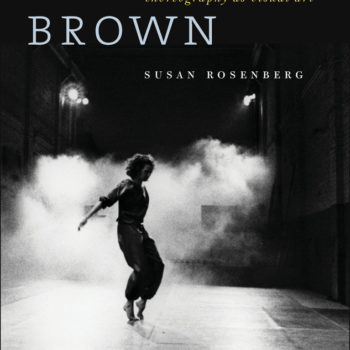

Trisha Brown: Choreography as Visual Art

Trisha Brown: Choreography as Visual Art The Selected Letters of John Cage

The Selected Letters of John Cage Swing Time

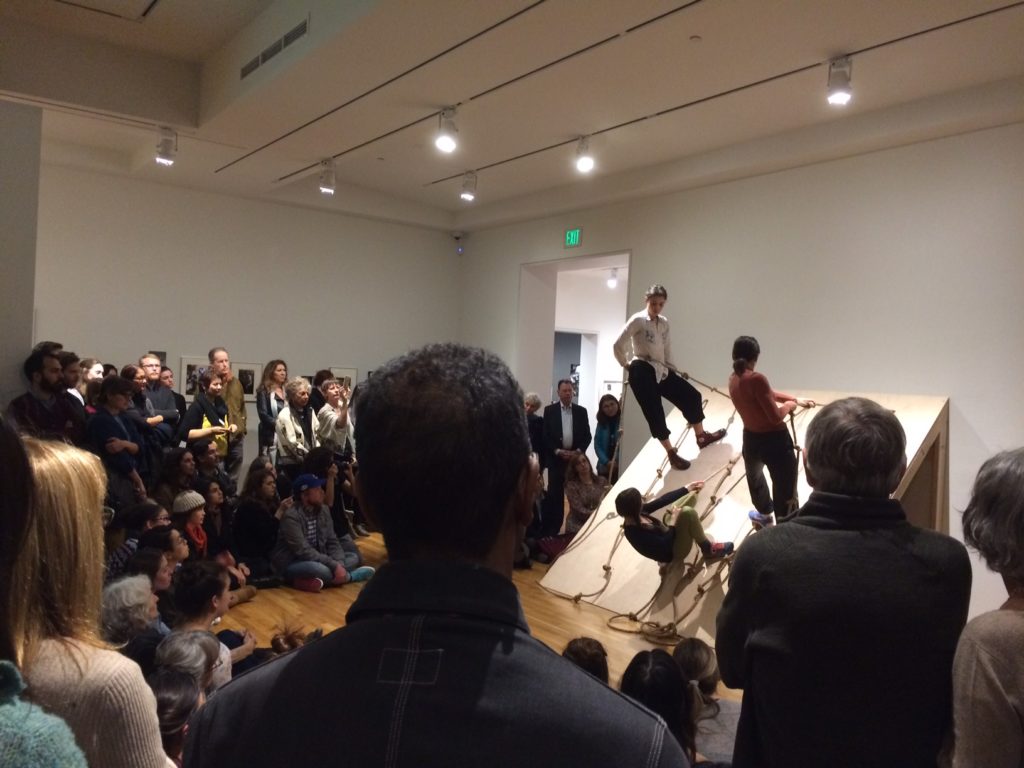

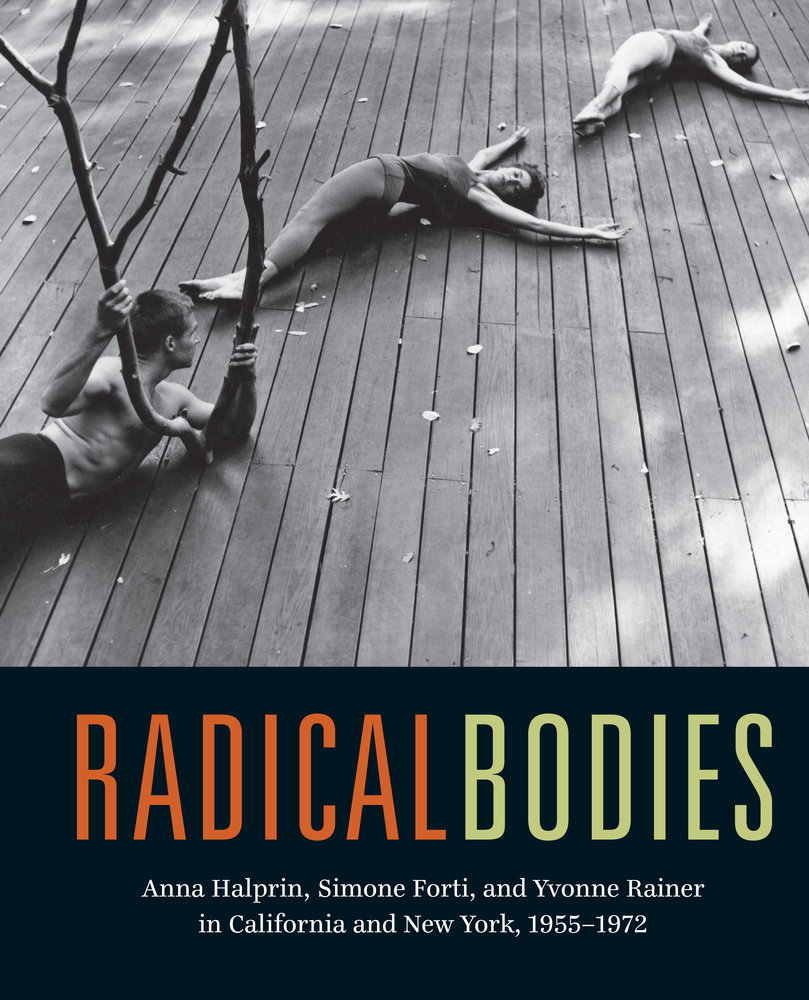

Swing Time Radical Bodies: Anna Halprin, Simone Forti, and Yvonne Rainer in California and New York, 1955-1972

Radical Bodies: Anna Halprin, Simone Forti, and Yvonne Rainer in California and New York, 1955-1972 Flowers Cracking Concrete: Eiko & Koma’s Asian/American Choreographies

Flowers Cracking Concrete: Eiko & Koma’s Asian/American Choreographies

Contemporary Directions in Asian American Dance

Contemporary Directions in Asian American Dance The Concrete Body: Yvonne Rainer, Carolee Schneemann, Vito Acconci

The Concrete Body: Yvonne Rainer, Carolee Schneemann, Vito Acconci Out There: Jonathan Porretta’s Life in Dance

Out There: Jonathan Porretta’s Life in Dance