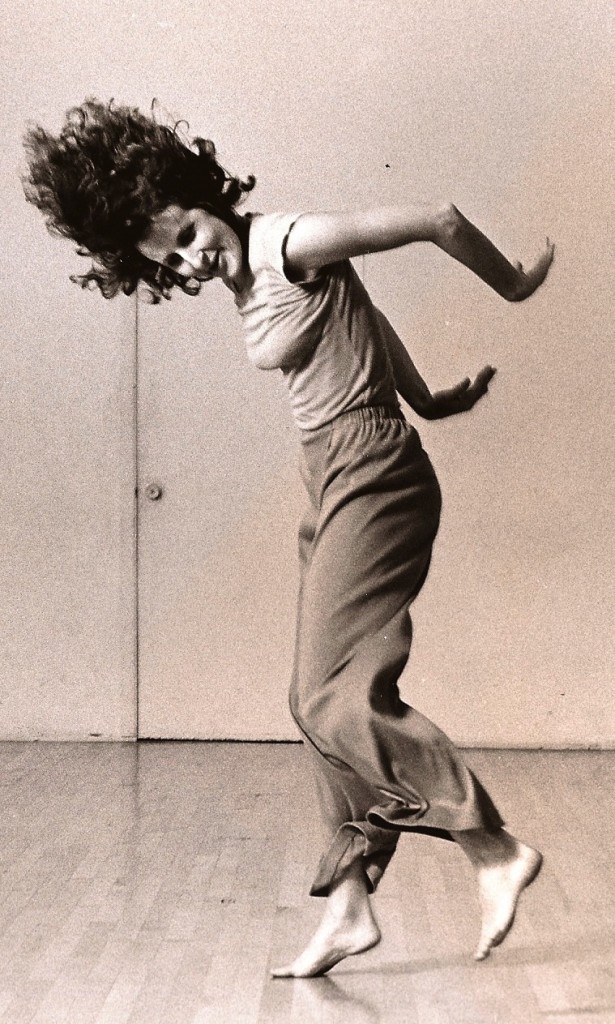

What does it mean that American Ballet Theatre has come out with a big new Sleeping Beauty? The production of Ratmansky’s new/old staging cost six million dollars (half of which is to be covered by the co-commissioning company, La Scala Ballet). I know I’m not supposed to think about money, just art. But while watching this production (twice), I couldn’t help but notice how extravagant it is—400 costumes and 210 wigs—compared to how little relevance the ballet holds for us today.

Tchaikovsky’s music is lushly beautiful. With its danceable waltzes and big dramatic bursts, it expresses the clash between anger and harmony that drives the narrative. But the tale is about an ancient kingdom that has only one worry: to make sure the daughter doesn’t get hold of a spindle. It’s not a ballet that stirs complex emotions or stimulates a train of thought about life’s dilemmas.

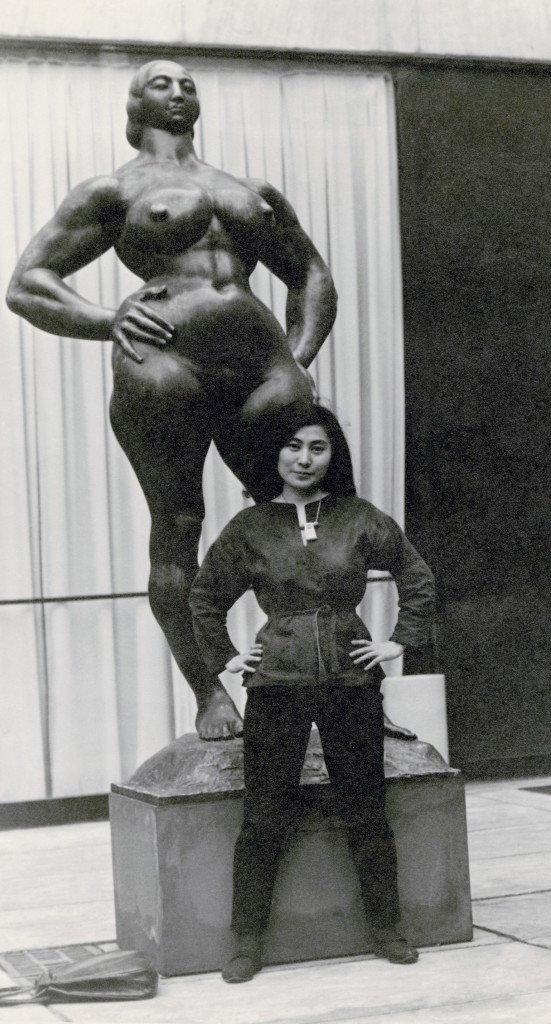

ABT in Ratmansky’s Sleeping Beauty: a 6 million dollar tab. All photos by Gene Schiavone.

The other ABT classics are perennials because they each have something that speaks to us today. The violence between the warring factions of Romeo and Juliet is always painfully relevant. Prince Siegfried in Swan Lake is searching for something that’s more spiritual than his materialistic upbringing; and Odette, who feels trapped, has to rely on a man’s faithfulness. We learn from Giselle that class differences can forbid one from marrying for love, and that recognizing your mistakes can change your life.

And then there’s The Sleeping Beauty. Sure, it’s about the battle between good and evil, but what’s the message? Be careful not to incur the wrath of a powerful person? Of course no ballet can be reduced to a single message—but this one comes close.

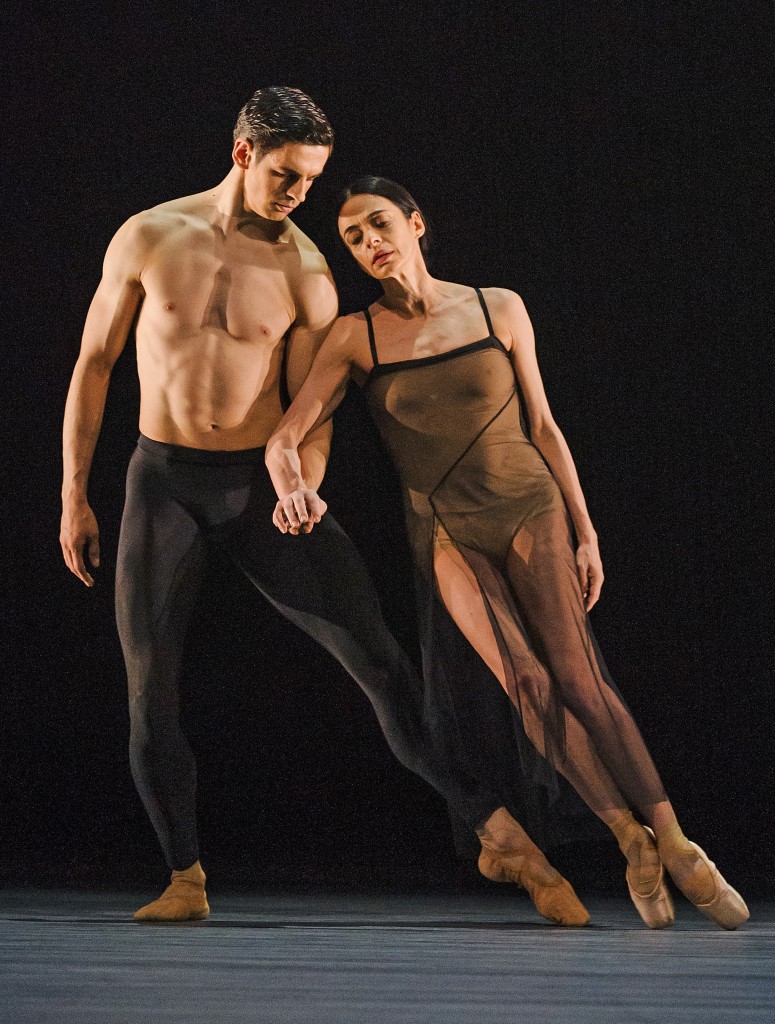

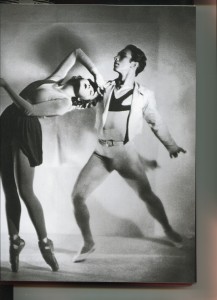

I applaud Ratmansky for immersing himself in the Stepanov notation and drawings of Petipa’s original 1890 version. It’s interesting that he was guided more by his passion for ballet history than his personal choreographic desires. I also applaud the dancers, especially Diana Vishneva and Marcelo Gomes, who imbued the leading roles with a shared spirituality. (Similar, as I wrote in 2011 in Dance Magazine, to the partnership of Alina Cojocaru and Johan Kobborg when they danced these roles in ABT’s last version.)

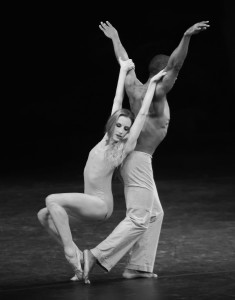

Diana Vishneva as Princess Aurora and Marcelo Gomes as Prince Désiré: shared spirituality.

But at a time when people around the globe are plagued by violence, racial issues, and environmental degradation, a story that focuses solely on the aristocracy can only serve as an escape. But is there some undercurrent to this type of escape? Is it also some kind of reinforcement of complacency? The audience can get swept up in the glory of Tchaikovsky’s music and the detail of Petipa’s steps, as researched by Ratmansky and his wife Tatiana. But in the end the ballet represents a very privileged population.

One of my colleagues suggested taking pleasure in the precision and communicative aspects of the dancing. But I find the predictable structure of the choreography a deterrent. When I see the many repetitions in the Garland Waltz, I imagine Petipa saying to his dancers, “Do three of these and one of those.” In steps as well as story, The Sleeping Beauty doesn’t measure up to the other classics.

In her Dance Tabs review, Marina Harss writes, “The real challenge isn’t replicating the steps but bringing them to life, and through them, channeling the spirit of the age. In this, it seems to me that Ratmansky has succeeded, producing a ballet that glows from within.”

I agree that the dancing is stamped with the spirit of the times. ABT has given us a piece of history, and there is value in that. Ballet historians are soaking this moment up. But for some of us, it’s like seeing lithographs of dainty ballerinas come to life. In this Sleeping Beauty I missed dancing that extends into space; I missed the directness that Balanchine has given us. Dance evolves for a reason. It adjusts to how cultures and bodies change.

Maybe I’ll get used to this Sleeping Beauty as one flavor in the pack of ABT’s repertoire—the old world flavor. But if this reconstruction was intended to be the centerpiece of ABT’s 75 years, it seems a misstep to me.

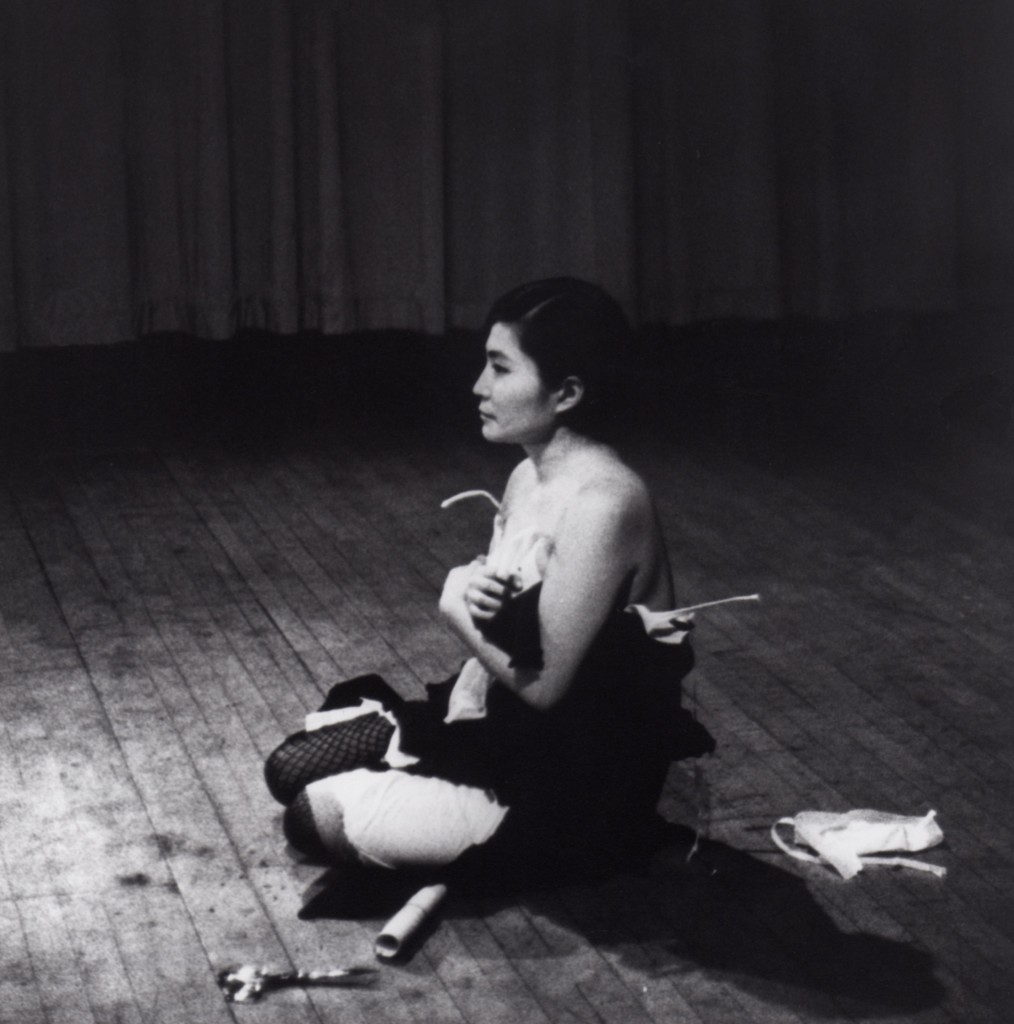

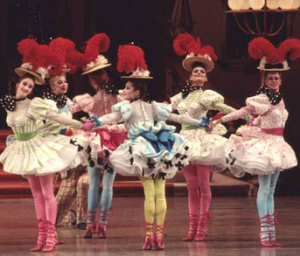

Finale of The Sleeping Beauty, with Lilac Fairy and Carabosse in background.

I can’t help but point out that the previous, equally anticipated new Sleeping Beauty for ABT premiered only eight years ago. It was assembled by esteemed dance artists Gelsey Kirkland and Kevin McKenzie, along with Michael Chernov, none of whom is a choreographer. It kept some traditional things and changed or condensed others. It created some beautifully tender moments that propelled the story. (Again, I cite my posting from 2011.) To my mind its worst mistake was not giving the prince a physical struggle to reach his goal. He did not have to fight to arrive at the castle.

And the Ratmansky version makes the same mistake. It’s too easy for Prince Désiré to find the love of his dreams. If he had to overcome the barrier to the castle, if he had to work hard and sweat, if he had to shed his princeliness for a few minutes, the ballet would offer some sense of a catharsis. In the New York City Ballet’s version, the prince whacks away the choking vines that have encrusted the castle for a hundred years. By the time he reaches Aurora, we feel he has earned her love.

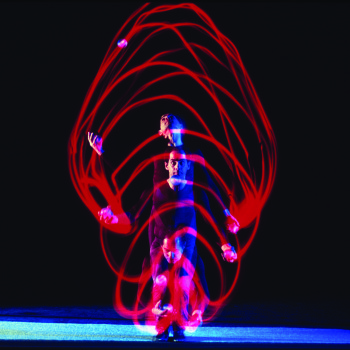

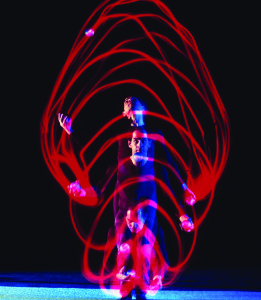

Isadora Loyola and Sean Stewart as the White Cat and Puss-in-Boots, Photo by Gene Schiavone.

But Petipa/Ratmansky’s Prince Désiré has no such grit. He has technical grit, e.g. difficult petit allegro, but no emotional grit. He sails easily, guided by the Lilac Fairy, from his vision of Aurora to the bedroom of Aurora. All the royal characters retain their royal calm in every scene. This production seems to say that beauty and harmony only reside in a smoothly running aristocracy.

That said, I was delighted that Ratmansky reinstated the storybook characters that add such fun to Aurora’s Wedding. The White Cat and Puss-in-Boots are particularly welcome, with their witty clawing and flirting.

So….will there be another Sleeping Beauty in eight years?

Featured Uncategorized 15