(Note: For my annual list of “Best and Worst of 2014,” click here.)

Endings As Beginnings

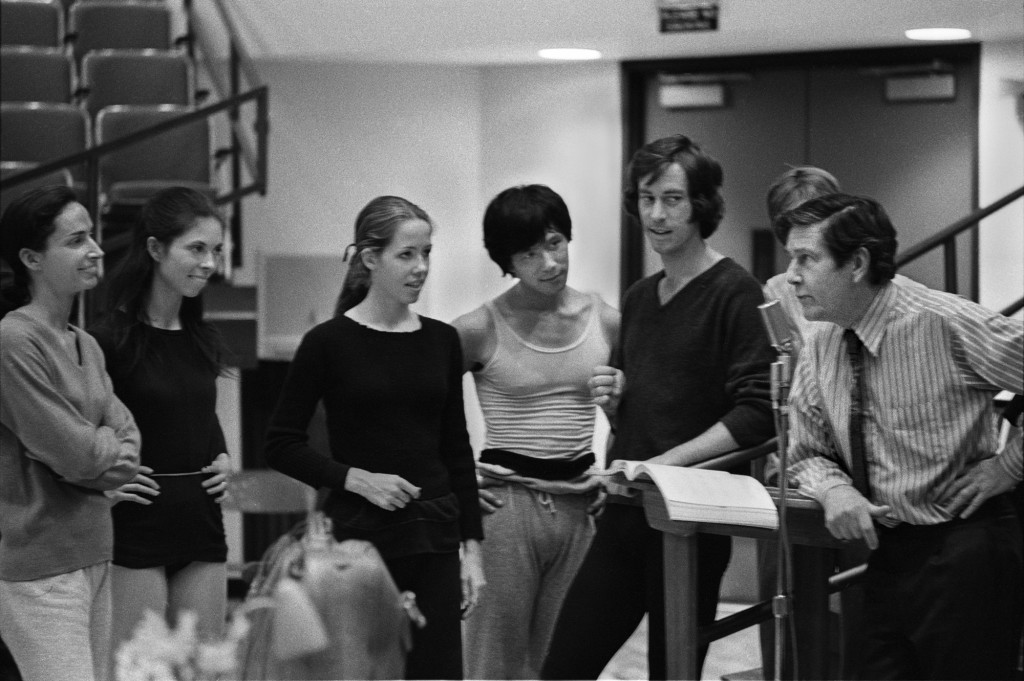

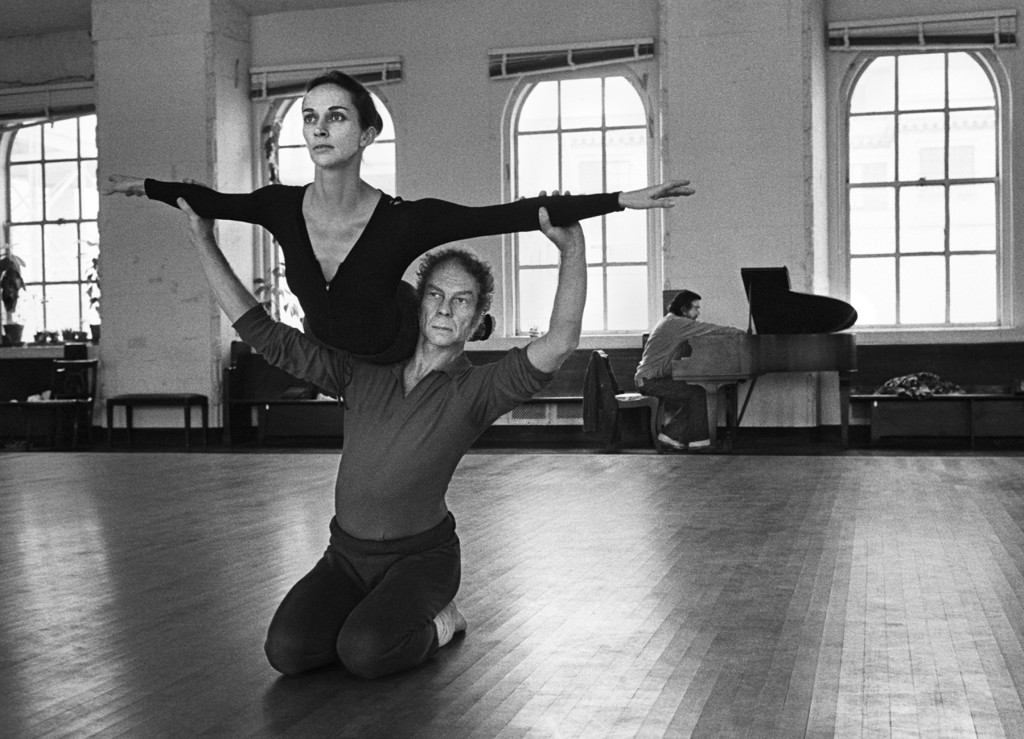

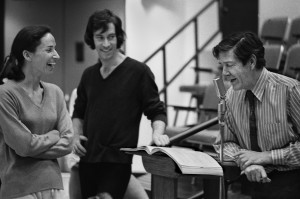

Wendy Whelan and Brian Brooks rehearsing Restless Creature, photo by Erin Baiano. Homepage photo of Danza Contemporánea de Cuba, by W. P.

• Wendy Whelan’s farewell turned out to be a joyous event. She radiated happiness that lit up the whole stage, and the other dancers basked in her sunlight. Even in the spontaneous moments she was utterly natural in her movement, accepting the waves of love from her audience graciously. When Jacques d’Amboise stepped onstage to pay his respects, he swept her up in a brief waltz. It was a wonderful sendoff to her new career as impresario, innovator, and modern dancer.

• After four decades as a duo, the famed Eiko & Koma are going their separate professional ways (for now). Eiko has embarked on a solo project, the haunting Body in Place series. (Koma is delving into visual arts; they are still together as a couple.)

• Obama’s pledge to open relations with Cuba will end the standoff and begin a new era of friendship between the U.S. and dance-rich Cuba. I’m not the only one who was celebrating at this news. Perhaps more U.S. dance companies will perform there, and maybe American students wanting to get Russian-style technique will study at the legendary National Ballet School in Havana. It’s tantalizing to think of the cultural exchanges that may ensue.

• So sad to see the last show of ABT’s magnificent, psychologically satisfying Nutcracker at BAM, with excellent choreography by Ratmansky. Next year the company will begin performing it annually at Segerstrom Center for the Arts in California, with whom ABT is also partnering to establish a new ballet school.

• DNA on Chambers Street went under, but their building was awarded to Gina Gibney by the Department of Cultural Affairs. The new Gibney Dance Center has gotten off to a roaring start, with many ideas for making it a hub of activity.

• The Trey McIntyre Project fell apart (here’s my guess why), allowing McIntyre more time for other projects. This news added fuel to the argument that the single-choreographer company model is simply outmoded.

Other Beginnings

• CUNY Dance Initiative: Someone figured out a win-win solution to the fact that choreographers need space and the 14 or so colleges in the CUNY system have studio hours to spare. The result is that a diverse group of dance have been awarded space on campuses in all five boroughs. While in residence, these dance artists may just unlock a love of dance in some students along the way.

Cathy Weis, photo by Jacques-Jean Tiziou, www.jjtiziou.net

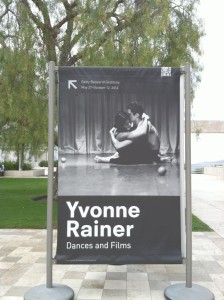

• The inimitable Cathy Weis has introduced a salon series called Sundays on Broadway in her SoHo loft. The videographer/choreographer welcomes her guests with drinks, a carpet to lounge on, and friendly discussion. The series launched with documentaries from the 60s (works by John Cage, Robert Rauschenberg and Yvonne Rainer and more). Sundays on Broadway has also presented works-in-progress by dance artists like Jennifer Miller and Jonathan Kinzel. It’s free, so take a look at the current calendar—in a couple weeks because the 2015 lineup isn’t posted yet.

Trends

• Ballet to gaga: Top ballet dancers are flocking to gaga as a way to expand their range—and maybe having a little experimental fun as well. Osipova and Vasiliev went to Tel Aviv to learn a work by Ohad Naharin and took his gaga sessions to get in the mood. Diana Vishneva invited Danielle Agami to teach a gaga workshop in her festival in Moscow, and I heard that Benjamin Millepied wants to import gaga for the Paris Opéra Ballet. Naharin is ready for this: He has said that gaga is a tool for ballet dancers as well as for modern dancers.

• California Women: When I traveled to the West Coast in June, almost everywhere I looked, both in the Bay Area and L.A. dance scenes, women were in charge. Long live the women’s movement!

• More transgender dancers: At Danspace, the Museum of Modern Art, and Baryshnikov Art Center, I’ve come across really good dancers who happen to be transgender. For a while it seemed to me that Seattle was leading the way on this, but now I realize that crossing gender borders is happening all over. I have no doubt that this particular kind of courage enriches the field.

• Profusion of reality shows: Seems like everyone from NYCB to Condé Naste Entertainment is producing reality shows on dance. I was even filmed for one of them (“Dance School Diaries” on the Dance On network), when I served as a judge in the Los Angeles YAGP. (I don’t think my footage was in the final episode but I didn’t have the patience to find out.) I suppose this is a good avenue by which kids all over the country learn about our field, but it’s not my favorite way to see dance.

What trends have you noticed in 2014?

Featured Uncategorized Leave a comment