We often complain that the leadership positions in dance are occupied mostly by men. And yes, that’s true in many places. But I have come to realize, after my short visit to the Bay Area and Los Angeles last month, that the women in California are the ones who have made the dance scene there.

Anna Halprin, photo by Kent Reno

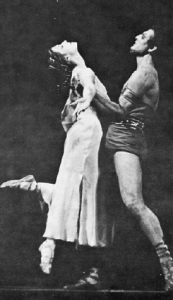

Let me start with the Bay Area and its three matriarchs: Anna Halprin, Brenda Way, and Margaret Jenkins. Halprin, the great forerunner of postmodern dance, settled there more than five decades ago, where her brand of improvisation, healing, and anarchy caught fire. (Click here for an update on her rituals, and here for info on the documentary on her.) She still gives classes and “performance labs” in her Mountain Home Studio, and her works have earned a flurry of popularity in Europe.

Brenda Way is the force and mastermind behind ODC Dance Commons, the buzzing hub of dance that offers a wide range of classes, plus the ODC Theater and the collaborative ODC Dance Company. Her intellectual curiosity is in evidence everywhere, from the design of the Commons, to the festival programming, to the choreography of the dance company, which she co-directs with KT Nelson and Kimi Okada.

Margaret Jenkins

Margaret Jenkins is a Cunningham disciple whose warmth and insights have encouraged many in the dance community. Her company, which just celebrated its 40th anniversary, collaborates with dance artists in China and Israel. She’s developed a mentorship program, CHIME, that helps nurture the next generation of choreographers.

The beautiful, haunting site-specific works of Joanna Haigood have won acclaim on a national scale. Another inspiring presence is Sara Shelton Mann, the dancer/educator who formed Contraband, a collaborative group of interdisciplinary artists. The dance departments of colleges and universities in the area, like Stanford and Mills, are also run by strong women.

The Smuin Ballet has not only been kept afloat by Celia Fushille since Michael Smuin’s death in 2007, but has opened up to many new choreographers. And Amy Seiwert’s Imagery, a contemporary ballet company, is going strong. Her annual SKETCH series (which happens to be at ODC Theater this week) encourages experimentation and collaboration while using the ballet vocabulary.

Other choreographers who thrive in the Bay Area are Hope Mohr, Nina Haft, Randee Paufve, Katie Falkner, Abigail Hosein, and recent transplant from NYC (and an old friend of mine) Risa Jaroslow. Amelia Rudolph with Bandaloop, is a leader in the aerial dance constellation. Krissy Keefer’s Dance Brigade, still resolutely rebellious/rambunction/revolutionary, is resident at the Dance Mission Theater, which offers tons of classes from ballet to Bhangra to Voguing. Being in the Mission District, the mural on the front of its building reflects San Francisco’s appealing craze for street art.

Dance Mission Theater building

Lula Washington

Moving down to Los Angeles, where it’s been notoriously hard to sustain a company in the shadow of Hollywood, two longterm leaders have trained generations of dancers. Lula Washingon, emphasizes the legacy of black culture in dance, and Debbie Allen’s Dance Academy embraces cultural and aesthetic diversity.

There are other major players who have been leading their companies for about a decade: Colleen Neary, co-director of Balanchine-based Los Angeles Ballet; Ana Maria Alvarez, whose urban Latin dance theater CONTRA-TIEMPO does major outreach; Jennifer Backhaus, director of the modern dance group Backhaus Dance; Judith Helle, a former ballet dancer with aerial chops who runs the Luminario Ballet; and Michelle Mierz and Kate Hutter, co-directors of the L.A. Contemporary Dance Company.

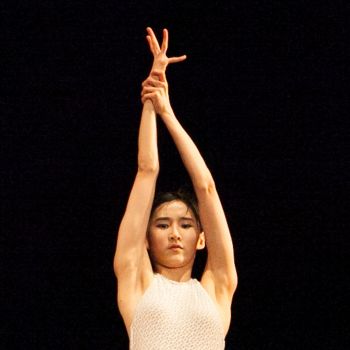

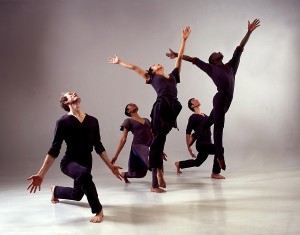

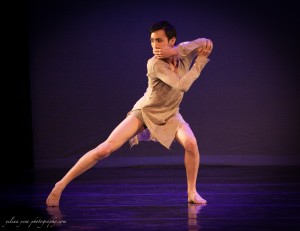

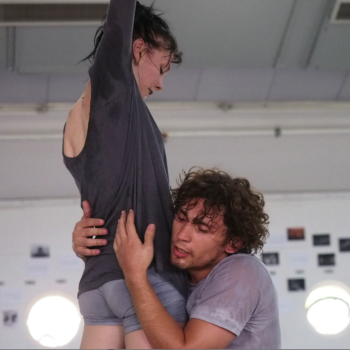

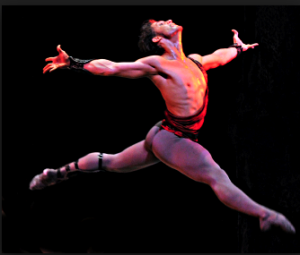

A handful of women-led companies have recently burst on the scene. BODYTRAFFIC is led by a team of two: Lillian Barbeito and Tina Finkelman Berkett. Melissa Barak, one of the very few women who has ever been commissioned by New York City Ballet, recently formed Barak Ballet. (At the moment, she’s making a solo for the sublime ballerinal Hee Seo.) And Danielle Agami, who emerged from Batsheva with that famous Israeli rawness intact, has gathered a group of terrific dancers for her Ate9 dANCEcOMPANY.

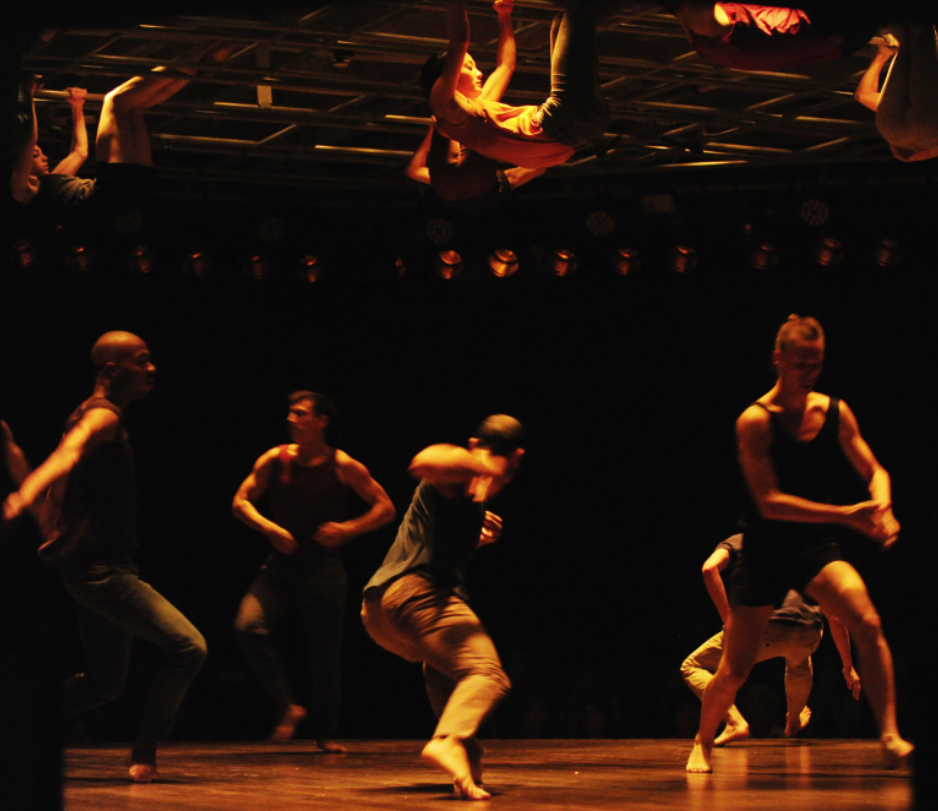

Ate9 dANCE cOMPANY, photo by Scott Simock

Then there’s the new and delightful fact that Jenifer Ringer will head the new Colburn Dance Academy, which is part of the reason I posted last month about L.A. becoming a destination for dance students.

Women as presenters or administrators have enlivened the L.A. dance scene enormously. Judy Morr at Segerstrom Center for the Arts insures that great touring companies visit Costa Mesa. (This month the blockbuster ballet duo of Natalia Osipova and Ivan Vasiliev premiere their out-of-the-box contemporary program at Segerstrom.) Renae Williams is vice president of programming at the Los Angeles Music Center, which just presented National Ballet of Canada’s production of Ratmansky’s fascinating Romeo and Juliet. The savvy curator of the Center for the Art of Performance at UCLA, Kristy Edmunds, is bringing top-level artists like Batsheva Dance Company and Kyle Abraham to Royce Hall this season.

On a smaller scale, Showbox L.A. is co-directed by Meg Wolfe, a dancer/choreographer transplanted from NYC. Tonia Barber as the new executive director of Dance Camera West has added a live performance component to its programs. (It was exciting to see Jason Samuels Smith and Chitresh Das dance together after the screening of the excellent documentary about them.) Also at Dance Camera West, Bonnie Oda Homsey, whose Los Angeles Dance Foundation carries the torch for modern dance, showed her documentary on historical figure Michio Ito.

Slews of choreographers who cross over between concert dance and commercial dance depend on Julie McDonald, founder of MSA Associates, as their agent. She guides the careers of many choreographers and dancers like Dance Magazine cover girl Tyne Stecklein.

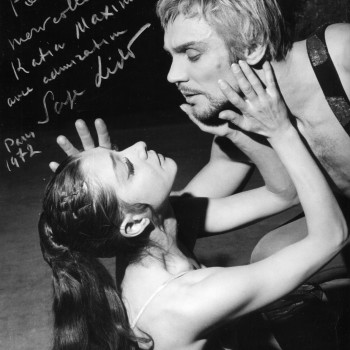

Simone Forti, photo by Gary Leonard, Courtesy LA Library Foundation

For anchors in the postmodern community, the legendary Simone Forti still performs her touching and witty solo improvisations. Victoria Marks, whose recent work has taken on a new gravitas, teaches at UCLA. (I had the honor of sharing a program with those two last month at the L.A. Library Foundation.) Heidi Duckler has been showing her ingenious site-specific works (I saw a fun one in the Mission Bowling Alley in San Francisco in June) regularly for the last 30 years.

Local critics who advocate for dance are also mostly women: Debra Levine of artsmeme.com, Victoria Looseleaf, Sara Wolf, Laura Bleiberg. A few years ago, a group of five women got together to start an alternative publication called ITCH. Former dance critic Sasha Anawalt runs the arts journalism degree program at University of Southern California. Also at USC is former Forsythe dancer Jodie Gates, who, with the help of dance philanthropist Glorya Kaufman, is taking making USC a hotspot for dance.

The entire California dance world is bolstered by brainy feminine presences, too abundant to name, in the University of California system. That includes UCLA, UC Irvine (which hosts Molly Lynch’s National Choreographic Institute), UC Santa Barbara, UC Berkeley, UC Long Beach, and UC Riverside.

Of course any dance scene in the U. S. has plenty of women as movers and shakers. But it strikes me that California has an unusually high proportion of them. Maybe this is not surprising—after all, the sunny state was the home of both Isadora Duncan and Martha Graham!

(Thanks to Lisa Bush and Debra Levine for filling in the gaps of my knowledge. If I’ve left out any major women leaders, please use the comments box below.)

Featured Uncategorized 27

With the drumbeat accelerating, the uneven earth commanding one’s attention so as not to fall, and the exhilaration of being among other runners (and walkers), it was easy to forget the purpose of the run. But at the end Anna brought us back to our purpose. She asked us to sit back-to-back with a neighbor for a few minutes, then face that person and tell her or him of our plans to bring our stated goal closer to reality.

With the drumbeat accelerating, the uneven earth commanding one’s attention so as not to fall, and the exhilaration of being among other runners (and walkers), it was easy to forget the purpose of the run. But at the end Anna brought us back to our purpose. She asked us to sit back-to-back with a neighbor for a few minutes, then face that person and tell her or him of our plans to bring our stated goal closer to reality.