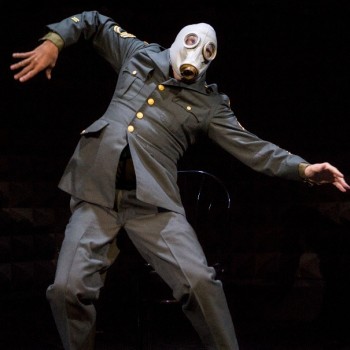

I was fascinated and appalled by Pina Bausch’s Kontakthof when I saw it in 1983. As I wrote at the time, “The work was amazing in its craft, its looniness, its integration of movement, text, acting and film—and its brutality.” The topic was heterosexual attraction, but each budding romance came up against a wall of stubbornness—bullying, actually—but with that special Bauschian obsessiveness that somehow turns it into art.

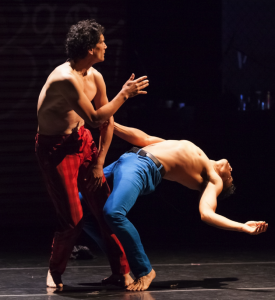

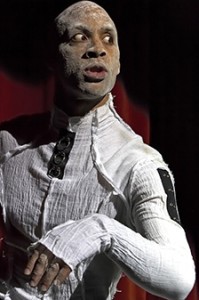

Kontakthof, photo by Oliver Look

The review is in my book of collected writings, page 69. In describing the piece further, I had written in the New York Native: “It consists basically of ten straight couples going through a cycle of seduction, molestation and separation with a few ghastly pleasures in between.”

So, am I recommending that you see Kontakthof when it comes to BAM Oct. 23 to Nov. 2? Yes, for two reasons. First, because Bausch’s work in the last decade of her life was so full of sensuality and delight—I’m thinking of pieces like Nelken and Bamboo Blues (which graces the cover of my book)—that we sometimes forget what an unflinching vision of male-female mayhem she could project. Second, because after Bausch’s death in 2009, the company can still fill the stage with many stories at once.

And maybe, just maybe, that edge of brutality has softened a bit. After all, Bausch chose this piece as a lens through which to look at two other age groups. A beautiful documentary (Dancing Dreams) was made about teenagers learning Kontakthof—with the brazen Josephine Ann Endicott as coach. (Click here for an amazing clip of that film.) And in England, Bausch made a version for people over 65.

And maybe, just maybe, that edge of brutality has softened a bit. After all, Bausch chose this piece as a lens through which to look at two other age groups. A beautiful documentary (Dancing Dreams) was made about teenagers learning Kontakthof—with the brazen Josephine Ann Endicott as coach. (Click here for an amazing clip of that film.) And in England, Bausch made a version for people over 65.

Photos by Oliver Look

So, how did it happen that I reviewed Tanztheater Wuppertal Pina Bausch a year before it first came to BAM in 1984? I had been invited to perform a solo at a gallery in Basel, Switzerland, and it turned out to be the same week her company appeared at the city’s Kunsthalle. I had a kind of love-hate reaction to it, but of course ambivalence is a time-honored position from which to write. Now I feel fortunate that my Bausch viewing stretches back that far, and I hope it stretches into the future too.

Talking about stories, when she received the Dance Magazine Award in 2008, Pina told a beautiful story about coming to New York as a Juilliard student. This was just a few months before she died, and we caught it on video.

To get tickets to Kontakthof, click here.

In NYC Uncategorized what to see Leave a comment