For those of us who actually enjoy summers in the city, Lincoln Center Out of Doors is icing (ice cream?) on the cake. Because the concerts are free, audiences tend to be huge and wildly enthusiastic. So I advise you to get there early if you want a seat up front. But it’s also pleasant to meander toward Damrosch Park Bandshell later on and observe the crowd from the back.

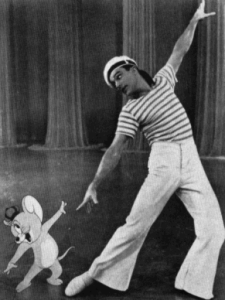

Rennie Harris Puremovement, Courtesy RHPM. Photo on homepage @ Christopher Duggan

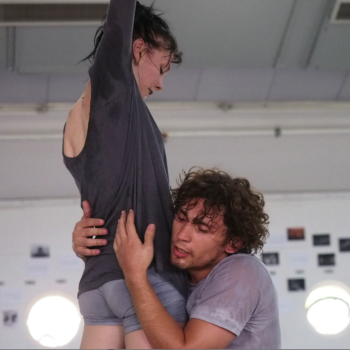

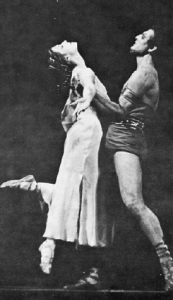

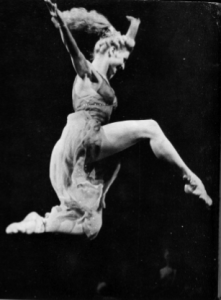

Pam Tanowitz Dance, photo © Christopher Duggan

This year, you can soak up the power of hip-hop culture on July 24, when Rennie Harris Puremovement—with three NYC premieres—shares a program with a Brazilian hip-hop group called A Batalha do Passinho. On July 25 you can see the clean ballet/Cunningham blend of Pam Tanowitz, who is paired with the music group Eight Blackbird.

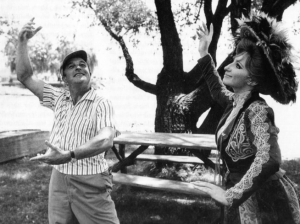

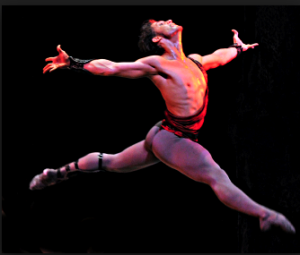

Mr. TOL E. RAncE, photo © Christopher Duggan

Next week brings Camille A. Brown with her dance-theater work on race, Mr. TOL E. RAncE, which was just nominated for a Bessie. A highly theatrical performer herself, Brown is both fearless and charming (see her Choreography in Focus). She is passionate about her chosen themes. On August 2, she shares the evening with another daring artist, the singer/songwriter Stew, who calls his current group The Negro Problem. So get ready for a smart, irony-drenched challenge to racism from two artists who have something to say.

For complete info on this series, click here.

In NYC Uncategorized what to see Leave a comment