During this horrible, hideous conflict between two peoples living so close to each other, I wanted to focus on peace-minded dance artists who have tried to foster understanding between Israelis and Palestinians. Can’t dance be a tool that helps scrape away old, stale hate and bring physical, spiritual understanding? Can’t people feel, under their dancing feet, a common ground? I did a little research and found that, yes, in some ways this has been happening.

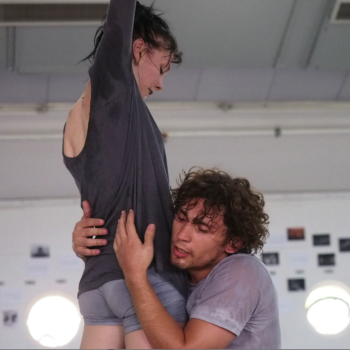

Dublin dance artist John Scott’s workshop in the West Bank

But when I did a little more research, I found that the rosy picture of togetherness I envisioned was oblivious to the realities of the Israeli occupation of the Gaza Strip and the West Bank. The Palestinians live under a system of restraints on travel and access to supplies imposed by Israeli law. So they are less eager for sharing workshops with Israeli dancers—even in periods that are relatively calm.

It seems to me that both peoples are at the mercy of their leaders’ stubborn (to put it mildly) insistence on revenge. But this is a lopsided situation, considering the power the Israeli government has over the Occupied Palestinian Territories (OPT), and that’s reflected in the disproportionate number of Palestinian deaths since the current war began a month ago. Needless to say, the threat of violence fosters distrust on both sides. Despite that, some dance artists are committed to addressing the tensions in whatever ways they can.

Working Together

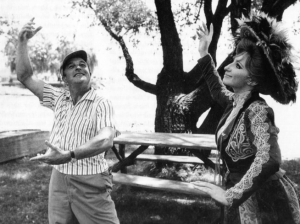

From the documentary Dancing in Jaffa

Ballroom maestro Pierre Dulaine (of Mad Hot Ballroom fame), has brought partner dancing to Jewish and Arab children in Jaffa, which borders on Tel Aviv (and is not under occupation). “What I’m asking them to do is to dance with the enemy,” says Dulaine in this trailer of the upcoming documentary Dancing in Jaffa. He teaches self respect first, then respect for another person. It starts here, dancing arm in arm with “the enemy.” What better way to dissipate distrust than touching a person’s upper back or shoulder with your fingertips at a tender age? This heart-warming film shows how children, through dance, can begin to shed the hatreds they have been taught. It will be released on DVD Aug. 12 from IFC Films and is available to pre-order on Amazon now.

“We Must Create Inner Debate”

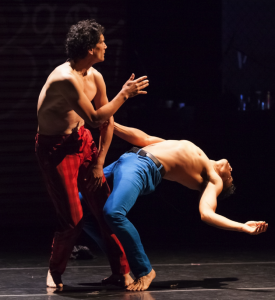

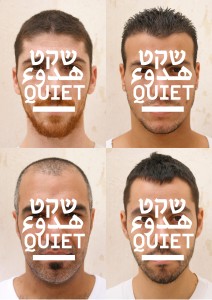

Graphic image for Quiet, with Arkadi Zaides on lower right, Dor Garbasg graphics-Avital Schreiber

Tel-Aviv–based choreographer Arkadi Zaides brought performers of opposing cultures together in his shattering all-male quartet Quiet. Two Israeli and two Arab performers grappled with situations of frightening aggression against self and other, tapping into intense rage, humiliation, and sorrow. When I saw it as a work in progress at the 2009 International Exposure in Tel Aviv, I found it almost unbearable to watch, yet thrilling for what it attempted to do. Zaides allowed fear, hatred, and self-loathing to erupt and cause a highly physical kind of mayhem, while harboring a faith that quiet would eventually be achieved. I was so convinced by the performers’ hard-won peace that I would have gladly nominated Zaides to take over the Israel/Palestine negotiations.

I recently spoke to Arkadi via Skype. “People are people,” he said. “We all have complex histories. The situation is uneven. It’s hard to communicate but we want to try and do it. In Quiet, we were working on physical polar resistance, a madness on the opposite side that resists touching. What does it mean to touch?”

Like Dulaine, Zaides believes in touch as a healing force, albeit with a completely different set of aesthetics. After working on other projects, Zaides sees the limits of touch—and collaboration in general. “Now I turn to my own community, asking questions before imagining any that address the opposite side,” he said. “Violence is perpetuating. Power is blinding. I cannot disconnect from more global questions. We are trying to build an understanding slowly, and these violent events are erasing those attempts. My new project is observing the growing violence within our own communities because this is what is troubling me as a person who doesn’t believe in violence as a solution.”

Zaides is aware that Palestinians cannot stop thinking about the occupation for one minute, so when they choreograph it is in some way about the occupation. Through Arkadi and others, I am beginning to understand why dancers in the OPT may not want to work with Israeli dancers. Israel has blocked and blockaded them from certain freedoms; for most Palestinians, the only Israelis they know are soldiers who enforce the occupation. Still, I was surprised when Arkadi used the word “boycott” to describe Palestinian artists’ attitude. “As a result of the operation in Gaza in 2008,” he said, “Palestinians have been boycotting any artistic collaboration with Israelis.”

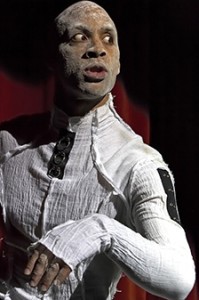

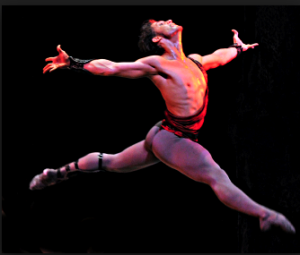

Arkadi Zaides in his solo Archive, at Avignon Festival, photo by Christopher Reynaud de Lage, video by B’Tselem Video Archive

For the time being, Zaides has stopped trying to collaborate. Instead, he came to the conclusion that “We must create an inner debate within Israel.” His new solo Archive, which just premiered in the Avignon Festival, embodies this idea of self-questioning. Using footage from the B’Tselem Video Archive of the Israeli Center for Human Rights in the Occupied Territories, he echoes or interacts with the shapes of the aggressors he sees on screen, thus absorbing the habit, the stance, of violence. According to the blurb in the brochure, “Arkadi Zaides never ceases to move around the stage, alternatively turning his body into a filter, a magnifying glass, a frame, or a mask, forcing us every time to change the way we look at things.” Zaides will perform Archive as part of the Diver Festival at Tmuna Theater in Tel Aviv, Sept 4 and 5.

Humor Lets You In

While Dulaine uses self-respect in his teaching and Zaides plunges his audiences into witnessing the violence within, other artists use humor to probe ethnic differences. Former Batsheva dancer Hillel Kogan made a talking/dancing duet titled We Love Arabs that was performed last year at Warehouse 2 in Jaffa. It included funny, brash scenes like Kogan smearing both their faces with hummus, a food staple in both cultures. Critic Ora Brafman of The Jerusalem Post called it “a true masterpiece…witty, provocative, political and hilarious…I chuckled and laughed and admired his mind, originality, as well as his deep stage comprehension.” (See a clip of it here.)

We Love Arabs, with Hillel Kogan foreground, and Adi Boutrous, photo by Gadi Dagon

The Arab in We Love Arabs was Adi Boutrous, who grew up in the south of Israel doing gymnastics and street dance. Now a contemporary dancer, he has created his own award-winning duet with his partner in life and work, Stav Struz, who is Jewish. You can see a clip of this wry, funny, intimate duet, titled What Really Makes Me Mad, which premiered at Suzanne Dellal Center last summer. As Boutrous has said, both he and she were willing “to deal with the Arab/Jewish issue” by bringing their private life onto the stage.

What Really Makes Me Mad, with Stav Struz foreground, and Adi Boutrous, photo by Gadi Dagon

Dialogue, Of Course

Conductor Daniel Barenboim, along with the late Palestinian-born cultural critic Edward Said, created an international youth orchestra to give Israelis and Palestinians the opportunity to make music together. When it performed in the OPT, it often faced controversy and verbal attacks. But all in the players believe in its mission, and they collectively wrote this statement in 2009: “We aspire to total freedom and equality between Israelis and Palestinians, and it is on this basis that we come together today to play music.” Anthony Tomassini wrote in The New York Times, “From the project’s start… Mr. Barenboim made no great claims for the transformative potential of the orchestra. But dialogue is a precondition to understanding. And dialogue is unavoidable when young musicians play music and live together.”

The Limits of Dialogue

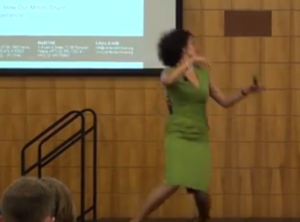

Nadia Aruri lecturing at Stanford

Under extreme circumstances, however, dialogue among artists can only go so far. One of the Palestinians who studied with Barenboim is Nadia Arouri, who founded a community dance project in the West Bank city Ramallah called I CAN MOVE to empower the marginalized. In a lecture at Stanford University, she played with audience expectations, saying, “My career as a terrorist started when I was 2.” (Click here to see her brilliant, inspired lecture.) She rejects all offers from Israelis to collaborate. Instead she urges Palestinians to work on themselves, as people who can develop their own resilience, as women who want to be treated as equals. Arouri talks about the effect that violence, both physical and verbal, has on our bodies. (“Can you visualize what all the hate messages do to us?”) She points out that many projects aimed at bringing the two sides together ultimately do not change anything for Palestinians. She is clearly less interested in bridging the divide between the two peoples than in the “healing process of peace for us as humans. It’s about finding peace in your surroundings, finding peace at home.”

Arouri demonstrating violence to the body

Arouri a moment later

Teaching in Occupied Palestinian Territories

Irene Siegel, an American who speaks Arabic fluently, has taught dance, physical theater, and yoga in the West Bank and Gaza. Now a professor of comparative literature at Hofstra, her last trip to the West Bank was last year. “There’s a kind of a hunger for contact with people from the outside with different kinds of technique and different kinds of art,” she said. Other than Dabke (also spelled debkeh and dabke), which is a traditional dance form that many Arabs are reclaiming as a form of resistance to the occupation, people there do not have access to other kinds of dance genres. “I worked with butoh, action-theater based and somatic techniques,” she said. “It would be challenging to get any group of young boys, even in the U.S., to do this kind of vocalizing and improvising. It was uncomfortable, but they threw themselves into it. It was moving to see.”

The constant restrictions of the occupation had an impact on her classes. “In almost every class I taught in the OPT, one or more of my students either couldn’t make it or were very late because they had been delayed or denied entry at an Israeli checkpoint. A grinding daily reality.”

Irene Siegel teaching a workshop in the Sareyyet Ramallah studio, 2011

In explaining the boycott to me, she said, “Palestinians from the OPT don’t have the option to go to Israel to collaborate because of the many restrictions, curfews, and checkpoints. But Israelis coming to the West Bank just to make collaborative art pieces with Palestinians not only seem self-serving to Palestinian artists; it is counter-productive. It allows Israelis to operate under the illusion that they can be disconnected from the Occupation, rather than implicated in it. It supports the idea that the conflict is between equal parties who are having a disagreement, and simply need to talk it out, or get to know each other better…”

In 2002, she had written this: “There is no one to hate here. I keep drawing back Gandhi’s words, like a protective layer against the pull of hatred: ‘We must hate the systems of oppression, not the individuals who are part of those systems.’ One of my most potent experiences — itself a kind of activism — was the act of listening.… During the time I spent in Palestine, I was flooded with stories, from people desperate to be heard, to finally break through the choking isolation of curfews and closures.”

How Does the Occupation Affect the Dancing Mind/Body?

Dublin choreographer John Scott collaborated with members of El-Funoun Dance Company of Ramallah and the Al Harah Theatre Company of Beit Jala, near Bethlehem. Scott found a direct relationship between their abilities in improvisation and the lives they lead. “When I taught the first workshop with the dancers,” he told me, “I tried a walking exercise I learnt with Pablo Vela and Meredith Monk. It involved an improvised walk through the entire space of the studio. But sadly, it took these talented young performers the longest time to acquire a freedom of movement in the space; their sense of space is so compromised from their living circumstances. But then, I got them to improvise with a wall and they all went wild. They really understood what a wall is!” (For more about the project, including the film Eternal that was made about it, click here.)

Performers from El-Funoun Dance Company and Al Harah Theatre Company in the film Eternal, directed by Steve Woods, choreographed by John Scott

Nicholas Rowe, an Australian dancer/choreographer who helped develop dance programs throughout the OPT for eight years, recalled a horrific incident in a 2003 keynote speech at the Dance and the Child International conference in Brazil. After giving a workshop near Hebron (outside Bethlehem) he and five male dance students were stopped at a checkpoint by young Israeli soldiers. They were slapped, punched, kicked, hit with rifle butts, and threatened with shooting. What Rowe, who is the author of Raising Dust: A Cultural History of Palestine, observed was that his students were accustomed to this kind of humiliation. “All live with the fear and expectation that it will probably happen again. What does this do to a dancing body? To the very physical aspect of a dancer’s freedom of movement? How does it affect an entire community of dancers, when they are all indiscriminately subjected to this sort of actual bodily control? Posture is becoming worse. A Palestinian Hump is evolving from the daily humiliations, cueing at the checkpoints.”

The Anxiety in Israel

I believe that most Israelis do not wish for the Palestinians to be treated this way. My friends in Tel Aviv have sympathy for Gazans but they feel frustrated, scared, and depressed about their own situation. It’s a relief that the Iron Dome deflects some of the rockets that Hamas is constantly shooting over—now with greater range than before—but one never knows when a siren is going to send you running into a shelter. It can happen during class, rehearsal, or performance. And most people in Israel have friends or children who are soldiers in harm’s way. They want to defend their country, but they know that revenge just begets more revenge and violence begets more terrorists.

Other Cross-Cultural Efforts

There have been many ways that Israelis have expressed respect for and a wish to share cultures. Ohad Naharin, director of the Batsheva Dance Company, collaborated with Arab musician Habib Alla Jamal, particularly in Naharin’s Virus (2002). And Batsheva is planning a year of programs in nearby Jaffa that would benefit Muslim, Jewish, and Christian children. Another Tel Aviv-based choreographer, Renana Raz, has worked with Dabke dancers from the Druze community, a minority in the north of Israel who have an Arab-based culture. And there are many more projects like these.

Dabke dancers from El-Funoun Dance Company in Yoshiko Chuma’s Love Story, Palestine at LaMama, photo by Hugh Burkhardt

In 2012 Yoshiko Chuma performed the multimedia Love Story, Palestine, at LaMama. It was basically about a piece she had made the year before in Ramallah, where her collaborators included members of the dance group El-Funoun. Many people in the company have traumatic stories. In the case of Noora Baker, a longtime member of El Funoun who became Chuma’s assistant, when she was 9 her parents were imprisoned for attending her first performance. Yoshiko did not attempt to act out these stories in Love Story, Palestine; instead she created an ambience of urgency through a basically absurdist collision of dance, music, film, and text. The anarchy cleared when two other other El-Funoun members, Sari Husseini and Anas Abu Oun, stomped out the steps of Dabke with great vitality. (Read a review here.) On the phone Yoshiko told me, “It took 10 years to understand what’s happening. I don’t show my emotions. I’m just listening. Their lives are 80 percent tragedy, 20 percent laughing.”

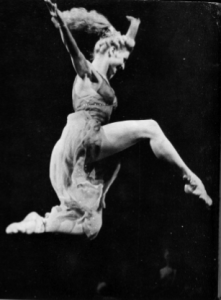

Anna Halprin’s Fervent Wish

The legendary Anna Halprin, 94, has been planning a trip to Israel this fall to work with Nadia Arouri as well as with Vertigo Dance Company, which has its own eco-arts village outside of Jerusalem. This will be Halprin’s last trip to Israel and it’s her dream to give people there her tools for a peace process and self-realization. She told me that she had planned an event with Nadia Arouri that would end with the Planetary Dance. “But now it’s getting so bad,” she says, “and everything’s in limbo.”

Anna Halprin with musicians in Jerusalem, 2010

Halprin with Druze woman who participated her the Walk for Peace, near Jerusalem

Four years ago Halprin conducted a Walk for Peace with women from all different religions. “They came to Jerusalem by bus from Gaza, the West Bank, the Druze section. It was a great moment when they arrived because everyone was hugging and kissing. There’s such an intense desire for peace, the women in particular.”

Right now, she says, “The current political crisis has been a heartbreak and makes you want to either back off or stand your ground more intensely.” Of course, the unstoppable Halprin will choose the latter. “I’m supposed to be performing with Vertigo at Suzanne Dellal Center,” she said on the phone. “And I want to work with Israelis and Palestinians together. I’m not going to back off.”

A Little Hope and a Lot of Desperate Prayer

After just scratching the surface enough to see a few of the harrowing complications of the ongoing Israel/Palestine conflict, I still believe in the power of dance to connect people. I offer this statement from the website of Barenboim’s West-Eastern Divan Orchestra. “Within the workshop, individuals who had only interacted with each other through the prism of war found themselves living and working together as equals. As they listened to each other during rehearsals and discussions, they traversed deep political and ideological divides.”

But I add a last urgent prayer from Israeli choreographer Neta Pulvermacher, now Dean of Dance for the Jerusalem Academy of Dance and Music in Jerusalem, who just sent me this: “It is an incredibly complicated, troubled, situation—where extreme beliefs rule…. But we people of this earth Want to LIVE IN PEACE ON THIS EARTH AND NOW! This is the only prayer that I really practice—every day, and every moment. I am tired of promised heavens for dead heroes of all kinds—our time, our lives on this planet is so brief… people of all sides and all beliefs should seize this brief moment…. cause you don’t get this life again…We should live now and in peace while we have the time. Choose life now and not heaven in your death. That is what I am thinking about when there are sirens… when I hear the booms… when I see the pictures of suffering on both sides.”

Thanks to Gaby Aldor, Melissa Barak, Nina Haft, Elena Hecht, Marianne Hraibi, Judith Brin Ingber, Naomi Jackson, Elizabeth Kendall, Lisa Kraus, Rachael Leonard, Debra Levine, Lisa Preiss, Colleen Thomas, Lisa Traiger, and Kathy Westwater, for giving me hints via social media.

Featured Uncategorized 15